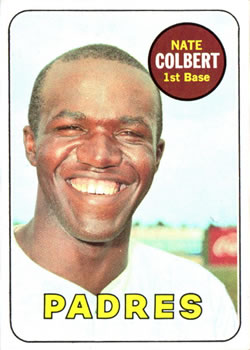

Nate Colbert

Nate Colbert wasn’t supposed to play on August 1, 1972. The San Diego slugger had injured his knee in a collision at home plate the night before and was listed as doubtful against the Atlanta Braves. Looking forward to hitting in Atlanta Stadium, known as the Launching Pad, Colbert decided to tough out the pain. He responded by belting a record-tying five home runs and driving in a record-setting 13 runs in a doubleheader. Colbert, an often-overlooked power hitter, averaged 30 home runs and 85 RBIs over a five-year stretch (1969-1973), becoming the expansion Padres’ first bona-fide star. Chronic back problems prematurely ended Colbert’s budding career after just 1,004 games and he retired after the 1976 season.

Nate Colbert wasn’t supposed to play on August 1, 1972. The San Diego slugger had injured his knee in a collision at home plate the night before and was listed as doubtful against the Atlanta Braves. Looking forward to hitting in Atlanta Stadium, known as the Launching Pad, Colbert decided to tough out the pain. He responded by belting a record-tying five home runs and driving in a record-setting 13 runs in a doubleheader. Colbert, an often-overlooked power hitter, averaged 30 home runs and 85 RBIs over a five-year stretch (1969-1973), becoming the expansion Padres’ first bona-fide star. Chronic back problems prematurely ended Colbert’s budding career after just 1,004 games and he retired after the 1976 season.

Born on April 9, 1946, in St. Louis, Nathan Colbert Jr. grew up in a predominantly African-American community on the city’s north side. His father, Nate Sr., was a former semipro Negro League catcher and occasional pitcher who instilled in Junior, his two brothers, and his three sisters an uncompromising work ethic and passion for sports. “I just loved baseball,” said Nate, whose fondest childhood memories included playing ball with his father and regularly seeing the Cardinals play.1 Young Nate enjoyed going to Sportsman’s Park, just about 10 minutes from his home, and marveled at his favorite players, among them Jackie Robinson, who once signed his glove, and Stan Musial. Nate was in the stands when Stan the Man belted five home runs in a doubleheader on May 2, 1954, a feat the youngster would duplicate some 18 years later.

Nate played baseball whenever he could, on nearby sandlots, and in the afternoons after attending Cole School. Nate Sr., who worked in a local mill, also coached baseball in a boys’ club and taught his son the fundamentals. “I was a little bigger than a lot of the kids,” Colbert told Wayne McBrayer of Padres360, “so baseball, it became easy to me.”2 At Charles H. Sumner High School, Nate dabbled in some football, but a knee injury convinced him to stay on the diamond. Tall and lithe, Nate seemingly glided in the outfield and on the basepaths and attracted major-league scouts who followed his progress in prep, summer, and local semipro leagues. According to Bruce Markusen, the New York Yankees were in hot pursuit and promised to double offers from any team;3 however, Colbert could only think of Cardinal red. Tracked by George Hasser, an area bird-dog scout for the Cardinals, Colbert was invited by Redbirds scouting director George Silvey to Busch Stadium (the official name of Sportsman’s Park since 1953) to hit a few balls for skipper Johnny Keane, who was impressed with the skinny kid’s power.4 Upon graduation in 1964, one year before the inauguration of the amateur draft, Colbert signed with the hometown team on scout Joe Monahan’s recommendation for a reported $20,000 bonus.

Colbert’s professional baseball career commenced just months later. The Cardinals assigned him to the Sarasota Rookie League, where the right-handed hitter split his time at first and in the outfield. His stint in the Redbirds organization was short. A fractured left hand in July ended his 1965 season with Cedar Rapids in the Class-A Midwest League.5 Colbert got some additional experience in the Florida Instructional League, but just weeks after that season concluded, he was selected by the Houston Astros in the Rule 5 Draft on November 29.

To call Colbert’s tenure with the Astros a disappointment is an understatement. Under Rule 5 stipulations, the Astros were required to keep him on their roster the entire season or risk losing him if they optioned him to the minors. The 20-year-old Colbert had just 504 minor-league at-bats and was completely unprepared to hit major-league pitching. After participating in the Astros spring training at Cocoa Beach, Florida, Colbert bided his time on skipper Grady Hatton’s bench. He made just 19 appearances (12 as a pinch-runner and 7 as a pinch-hitter) and did not play in the field, not even an inning. He went hitless, though he scored three times. “It was just a year lost as far as playing is concerned,” said Colbert bluntly.6 The highlight of Colbert’s season took place on July 27 when he married Carol Ann Allensworth, whom he had met while completing three weeks’ training in the Army National Guard in Oklahoma City.

Colbert worked the rust off his atrophied skills in another stint in the Florida Instructional League, then faced major leaguers in the Venezuelan League with Caracas. More than anything, the 6-foot-2, 200-pound Colbert needed at-bats, and was consequently assigned following another spring training with the Astros to the Amarillo Sonics in the Double-A Texas League. Colbert showcased his power and speed, pacing the circuit in home runs (28) and stolen bases (26). He was the league’s MVP, a unanimous All-Star, and was named to the Double-A Topps-National Association All-Star team. The young slugger was fully aware that he was still learning how to hit. “When I started, I didn’t know much, and swung hard. Now I don’t swing as hard, but hit the ball just as far,” he said in 1967. “I use my wrists and reflexes more now to give me power.”7

Assigned to the Triple-A Oklahoma City 89ers to start the 1968 season, Colbert was moved to center field to take advantage of his speed. A two-week call-up in July to the Astros proved disastrous (3-for-22). His first major-league hit was a single off fireballer Jim Maloney of the Cincinnati Reds. He was returned to the PCL, but broke his hand and played in just 92 games. He was healed enough for another two-week look-see with the Astros in September. The results weren’t much better than his first stint (5-for-31) and he was still homerless in the majors.

“You can destroy a man’s confidence,” said Colbert, recalling his struggles with the Astros. “[Manager] Harry Walker almost destroyed mine.”8 Walker was determined to mold Colbert into his own image, a spray hitter to all fields, and constantly tinkered with his swing. A natural pull hitter, Colbert was told to wait longer for the ball, and his timing suffered, as did his power. “I got so confused, I began to doubt myself. I thought I’d never find myself again. I was terrified. Here I was 22 years old and I was being told I couldn’t hit big-league ball.”9

Colbert’s stock had dropped so dramatically that the Astros made him available in the expansion draft. The San Diego Padres selected him with their 18th pick on October 14, 1968. “I had no way of checking to see if I had been drafted,” explained Colbert about the days before access to around-the-clock sports news via Internet and social media. “So, I stayed up and I kept calling the newspaper. I was in Oklahoma City. And they said, ‘Well, we’ve got nothing yet.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, come on.’ So, the next morning, [GM] Eddie Leishman from the Padres called me to welcome me. … And I just let out a yell because I wanted to go to the San Diego Padres.”10 Leishman, who had been GM of the PCL San Diego Padres in 1968, was well acquainted with Colbert (“Nate used to hurt us.”) and was convinced that he would blossom into a star if he had a chance to play.11

After playing with Estrellas in the Dominican Winter League, Colbert reported to the Padres camp in Yuma, Arizona, relishing the opportunity to reset his career. “[T]he first spring training was really a unique experience, because I was with 30 or more players, most of whom I did not know,” recalled Colbert.12 The spring facilities at Keegan Field on 24th Street in Yuma were primitive. A former youth baseball field in shabby condition, the entire infield and outfield needed to be leveled and the mound elevated to major-league standards. It also lacked basic amenities, such as bleachers, dugouts, showers, locker rooms, a press box, a PA system, and concession stands.13 “We showered in a city gym, in a recreation center,” recalled Colbert.14 The 23-year-old slugger probably wondered what he had gotten himself into, but noted that “we survived.” Padres players dressed and showered at the Kennedy Swimming Pool, while visiting players traveled across town to do the same in Municipal Stadium, the former spring home of the Baltimore Orioles, which was in even worse shape than Keegan.

Skipper Preston Gomez took a decidedly hands-off approach to Colbert’s swing and gave the youngster the freedom to rediscover his stroke. “Colbert has a quick bat,” said Gomez, “probably the quickest on the club.”15 Nonetheless, Colbert began the season as the backup first baseman to the Jolly Green Giant, 6-foot-7 Bill Davis. About two weeks into the season, Colbert took over for the slumping Davis and held down the first-base bag for the next five seasons. His breakout game had an air of revenge. On April 24 in the Astrodome, Colbert blasted his first career home run, a game-winning three-run shot in the eighth off Jack Billingham. The next day he whacked his first home run in San Diego Stadium, a solo shot off Reds fireballer Jim Maloney, and he clouted his third home run in as many days when he connected off the Reds’ Jim Merritt for a three-run dinger which also proved to be the game winner, in the eighth. Those contests inaugurated an eight-game stretch in which Colbert went 11-for-30, hit five home runs, and drove in 12 runs, becoming the Padres’ first star and fan favorite. Colbert was having the time of his life playing for the Padres in what he called “big, but beautiful” San Diego Stadium. “I kept saying, ‘It’s the big leagues. It’s the big leagues.’ You know, I know we don’t have a lot fans or a lot of money, but this is major league baseball. This is my goal.”16

He was also reaching some home-run milestones. In the first game of a twin bill on May 25, in front of 13,115 hometown fans, almost twice the Padres’ major-league-low 6,333 average, Colbert took the Chicago Cubs Don Nottebart deep for his first of six career grand slams. Six days later, against the Expos in Montreal, he belted two home runs in a game for the first of 14 times in his career and seemed destined for a berth on the All-Star squad. On June 11 he was batting .299 with 12 home runs and slugging .588 (fourth best in the NL), then reported to Oklahoma City for three weeks of service in the National Guard. A weekend pass enabled to him join the Padres for a four-game series in Houston, but Colbert didn’t rejoin the team permanently until June 30 and subsequently struggled mightily. In his next 25 games he batted just .180 with a sole home run in 100 at-bats. “My timing was off and I started to pull everything,” said Colbert.17 He rediscovered his stroke, slugging .516 from August 1 through the rest of the season to lead the offensively challenged team with 24 home runs, 9 triples, and 66 RBIs. The Padres finished with the worst record in baseball (52-110) and ranked last in majors in runs scored (averaging just 2.89 per game), batting average (.225), and on-base percentage (.285).

After another year of winter ball, earning all-league honors with Caguas in Puerto Rico, Colbert arrived at the Padres’ brand-new training facility in Yuma with heightened expectations. His spring-training performance foreshadowed his season: He knocked in 21 runs in 60 at-bats and hit a 500-foot home run that Oakland A’s coach Bobby Hofman called the longest he had ever seen.18 On Opening Day, the 24-year-old walloped a monstrous three-run blast off Phil Niekro in the Padres’ 8-3 victory against the Atlanta Braves. “If I stay healthy, I have a chance to hit 30,” said Colbert, who doubted he could reach the 35 mark his skipper Gomez predicted.19 The round-trippers kept coming. He whacked four in 17 at-bats in a three-day, four-game stretch on the road on May 6-8, including two in one game against the Phillies in the City of Brotherly Love. “[Colbert can] hit a ball as far as anyone,” gushed Gomez, who compared his slugger to the hardest hitters in the game, such as Willie McCovey and Willie Stargell. “The ball just jumps off his bat.”20 Colbert blasted his former team on May 15, reaching two more milestones, by cranking his first extra-inning and first-walk-off home run, a two-run blast in the 10th to give the Padres a 10-8 victory.

Despite Colbert’s success (he was tied with Hank Aaron, Dick Allen, and Tony Perez for the major-league lead with 16 home runs after hitting two against the San Francisco Giants in the first game of a twin bill on May 26), Colbert’s name barely registered on the national radar. He was even left off the All-Star ballot (fans were given the right to vote in 1970 for the first time since the Cincinnati Reds ballot-box-stuffing scandal in 1957). “I could be leading the league in home runs and runs batted in and hitting .300 and people wouldn’t know who I am,” Colbert complained.21 A 21-game homerless streak to begin June dropped him well off the NL lead, and his name further receded from national attention. After spending the All-Star break at home in San Diego, Colbert equaled his home-run output from the first half by belting 19 as the Padres kept losing, finishing with the league’s worst record (63-99). In a strange statistical anomaly, the Padres ranked third in the league in home runs (172), easily led the majors with 104 on the road, yet ranked 11th of 12 NL teams in scoring. Colbert (38-86-.259 and .509 slugging) formed with his roommate Cito Gaston (29-93-.318, .543) and Ollie Brown (23-89-.292 .489) one of the most potent trios in baseball. A free swinger, Colbert finished in the NL’s top nine in strikeouts in all six of his full seasons in the majors, including third in 1970 with 150 punchouts. On August 12, he became part of strikeout history when the St. Louis Cardinals Bob Gibson fanned him for the hurler’s 200th K of the season to become the first major-league pitcher to reach the 200-strikeout mark in eight seasons.

Despite Colbert’s success (he was tied with Hank Aaron, Dick Allen, and Tony Perez for the major-league lead with 16 home runs after hitting two against the San Francisco Giants in the first game of a twin bill on May 26), Colbert’s name barely registered on the national radar. He was even left off the All-Star ballot (fans were given the right to vote in 1970 for the first time since the Cincinnati Reds ballot-box-stuffing scandal in 1957). “I could be leading the league in home runs and runs batted in and hitting .300 and people wouldn’t know who I am,” Colbert complained.21 A 21-game homerless streak to begin June dropped him well off the NL lead, and his name further receded from national attention. After spending the All-Star break at home in San Diego, Colbert equaled his home-run output from the first half by belting 19 as the Padres kept losing, finishing with the league’s worst record (63-99). In a strange statistical anomaly, the Padres ranked third in the league in home runs (172), easily led the majors with 104 on the road, yet ranked 11th of 12 NL teams in scoring. Colbert (38-86-.259 and .509 slugging) formed with his roommate Cito Gaston (29-93-.318, .543) and Ollie Brown (23-89-.292 .489) one of the most potent trios in baseball. A free swinger, Colbert finished in the NL’s top nine in strikeouts in all six of his full seasons in the majors, including third in 1970 with 150 punchouts. On August 12, he became part of strikeout history when the St. Louis Cardinals Bob Gibson fanned him for the hurler’s 200th K of the season to become the first major-league pitcher to reach the 200-strikeout mark in eight seasons.

Considered among the toughest parks for home-run hitters, San Diego Stadium had a deep 420-foot center field, with 375-foot power alleys, all of which were made even more imposing by a 17-foot outfield wall. “Whitey Wietelmann, one of our coaches, drew an imaginary line on his scorebook on what the dimensions were in most of the other ballparks,” recalled Colbert. “And then he took where I hit every ball and he said every year routinely, I would hit 15 to 20 balls that would be off the walls, on the warning track in deep center, that would have been home runs in another ballpark.”22

Colbert achieved success despite cognitive degeneration of his vertebrae which caused chronic lower back pain throughout his baseball career. “I have trouble getting loose,” he explained, adding that he acclimated himself to the discomfort. “I feel tight a lot at the start of games and I try to compensate and wind up swinging at bad pitches. I’ll have this problem all my life.”23

Colbert’s ailing back limited his participation in spring training in 1971 and raised concerns about the long-term effectiveness of the 25-year-old. Nonetheless big Nate was ready when the season commenced and he slammed two home runs against the San Francisco Giants in his second game of the season. Four days later he victimized Don Sutton of the Los Angeles Dodgers for two home runs in his first two at-bats en route to six RBIs in the Padres’ 9-7 victory on April 11, leading sportswriter Ross Newhan of the Los Angeles Times to declare him “baseball’s best young slugger.”24 Shrugging off those lofty pronouncements, Colbert developed a reputation as an emotionally charged team player who vented his frustrations after his strikeouts, but also at Padres fans, whom he once described as “impatient” and chided them for the “empty seats” in San Diego Stadium.25 The club finished last in the majors in attendance in 1971 for the second time in three years, averaging 6,883 per game. “I just want the team to be recognized,” Colbert said. “If the team gets recognition, I will, too. Recognition is tough when you play for a last-place team.”26 The club extended its cellar-dwelling streak in the NL West to three years; however, Colbert earned a berth on the All-Star team (selected by skipper Sparky Anderson of the Reds) and struck out against the Baltimore Orioles’ Mike Cuellar in his only plate appearance. Suffering through severe bouts of back pain, Colbert saw his power numbers drop, though he still led the team in home runs (27), RBIs (84), and slugging (.462), while batting .264 for the lowest-scoring team in baseball (3.02 runs per game).

Colbert enjoyed a magical 1972 season even while the Padres finished in the NL West cellar yet again with the league’s lowest-scoring offense (3.19 runs per game). He arrived at spring training at a chiseled 215 pounds, having dropped about 25 pounds by “taking shots,” reported sportswriter Phil Collier.27 Eleven games into the season, delayed by 13 days because of the first players strike in major-league history, Don Zimmer replaced Gomez as skipper. Soon thereafter Colbert commenced one of his patented tears by hitting a home run and driving in a pair of runs on May 5 against the Mets, who had tried to pry the slugger away from the lowly Padres in the offseason. Eight days later, Colbert concluded a seven-game stretch on the road with five home runs and 12 RBIs and was leading the majors with nine round-trippers. He began one of the worst slumps of his career the next day, managing just 14 hits in his next 107 at-bats as his averaged plummeted to .194. A surge in July (8 home runs and 19 RBIs in 20 games) catapulted Colbert back among the league leaders in those categories and garnered him another berth on the NL All-Star squad. In the bottom of the 10th, Colbert, pinch-hitting for pitcher Tug McGraw, drew a walk off Dave McNally. Two batters later he scored the dramatic winning run in his home-away-from home, Atlanta Stadium, on Joe Morgan’s single. After gaining some national recognition with that game-deciding tally, Colbert continued his July hot streak by homering in his first game after the All-Star Game, and then adding two more and knocking in all three Padres runs in a loss to the Astros at the Astrodome, setting up his fateful afternoon against the Braves in Atlanta on August 1.

Ever since Colbert was a minor leaguer with Amarillo, in 1967, he had a routine when he stepped into the batter’s box. “As I walk up to the plate,” he said, “I automatically touch my helmet. It gets me thinking about what I want to hit. Then I draw a Roman numeral seven in the dirt, backwards, with the end of the bat. I don’t know why I do it. It just do it. It clears my mind.”28 Leading the majors with 25 round-trippers, Colbert wielded his 35-inch, 36-ounce bat to go 4-for-5, belting two homers and driving in five runs in the Padres’ 9-0 laugher in the first game. Colbert recalled that he had felt exceptionally tired when the club arrived in Atlanta from Houston late the night before. “I didn’t sleep well,” he said. “I knew there was no way I could play both games. My back hurt, I felt down.”29 After his performance in the first game, there was no question he’d back in the field in the nightcap. He torched three different Braves hurlers to cap the best game of his life, clubbing three home runs for the first and only time and knocking in a career-high eight runs in the Padres’ 11-7 victory for the twin-bill sweep. Colbert’s five home runs tied Musial’s record for the most in a doubleheader and his 13 RBIs set a new record, breaking the mark of 11, held jointly by Earl Averill (1930), Jim Tabor (1939), and Boog Powell (1966). Colbert’s 22 total bases broke Musial’s record of 21. Given the Padres’ lack of home-run threats (Leron Lee was the only other player to have double-digit round-trippers that season with 12), it’s a wonder that opposing pitchers even threw to Colbert. He finished the season by tying his own club record with 38 home runs (finishing in second place in the majors, two behind Johnny Bench). Colbert’s 111 runs batted in set an intriguing major-league record, which still stood as of 2018, and might be among the baseball records least likely to be broken. His RBI total accounted for 22.75 percent of all the Padres’ runs, breaking the mark set by the Boston Braves’ Wally Berger (130 RBIs, 22.61 percent) in 1930.30

No one could have imagined that Colbert would go from one of the game’s most feared sluggers in 1972 to out of baseball four years later at the age of 30. The initial signs of Colbert’s alarming decline came in the first three months of the 1973 season, when he managed just seven home runs through June. A hot streak to start July (18 hits in 36 at-bats in nine games) helped salvage his season and earned him another berth on the All-Star squad. (He fouled out in his only appearance.) Once again the biggest offensive threat on the NL’s worst team and the lowest-scoring (3.38 runs per game) club in the majors, Colbert posted career bests in batting average (.270) and on-base-percentage (.343), though he slipped to 22 home runs and 80 runs batted in.

In his final three campaigns (1974-1976), Colbert batted an anemic .186 with a .346 slugging percentage and hit only 24 home runs. After three consecutive All-Star Game appearances at first base, Colbert was moved by the Padres to left field in 1974 to accommodate the acquisition of Willie McCovey. Colbert never acclimated himself to the new position, struggled at the plate, drew the ire of the fans, and was ultimately benched by skipper John McNamara. In the offseason he was traded to the Detroit Tigers. A short, disastrous stint in the Motor City was followed by a similar one with the Montreal Expos, who released him on June 2, 1976. Signed by the Oakland A’s, Colbert attempted to revive his career in the minors with the Tucson Toros of the Pacific Coast League. He was called up by the A’s in September and went hitless in two games. Granted free agency on November 1, 1976, Colbert was not selected in the inaugural free-agent re-entry draft, effectively ending his career. He participated in the Toronto Blue Jays spring training in 1977, but was jettisoned well before camp ended.

The Padres’ first star and multiple All-Star, Colbert finished his career with 173 home runs, 520 RBIs, and a .243 batting average. As of 2018, he still held the Padres’ career record for home runs (163) and ranked among the club’s top 10 in numerous offensive categories.

Like many ballplayers, Colbert’s transition into life after baseball was initially rocky. After holding down a few odd jobs and divorcing in 1979, Colbert married Kathrien (Kasey) Louis Barlow and became an ordained minister. He also gradually found his way back to the Padres, serving as an instructor during spring training and later as hitting coach for several seasons with the Riverside Red Wave in the Class-A California League. In October 1990, the day Colbert lost his job with the Padres, he was also indicted on 12 felony counts of fraudulent loan applications.31 He eventually pleaded guilty to one count and served a six-month sentence in Lompoc, a medium-security penitentiary in California.32 After his incarceration, Nate rededicated his life to his ministry and operated various baseball schools and camps in which youngsters learned about the sports and Christian values. He managed in two short-season independent leagues (Western Baseball League and Big South League) in 1995 and 1996, though he preferred to spend his time working with disadvantaged youths and combining his two passions, baseball and ministry. In 1999 Colbert, 1976 Cy Young Award winner Randy Jones, and former Padres owner Ray Kroc were the inaugural inductees into the Padres Hall of Fame, founded in 1999 on the team’s 30th anniversary. Colbert continued his ministry work into the new millennium. As of 2018, he lived in the San Diego area and occasionally made appearances with the Padres.

“I never had a bad day in baseball,” said the soft-spoken Colbert decades after retiring. “It was, I woke up, I wanted to go to the ballpark. I liked playing every day. I didn’t need an offday. I played with a bad back, broken toe, fractured wrist, and concussion. I played. I just played, because I figured I’m going to hurt anyway, so I might as well play.”33

Colbert died on January 5, 2023 at the age of 76.

Last revised: Januar6, 2023 (ghw)

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Colbert’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 “The Padres First Star — #17 –Nate Colbert,” Padres360, August 21, 2014. https://padres360.com/2014/08/21/the-padres-first-star-17-nate-colbert/.

2 Ibid.

3 Bruce Markusen, “#Card Corner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert,” baseballhall.org. https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/card-corner/nate-colbert.

4 Arnold Hano, “Nate Colbert Is Definitely Accident Prone,” Sport Magazine, May 1973: 50. Neal Russo, “Colbert’s Brother Says Father Inspired Nate,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 8, 1971: 29.

5 Jim Sims, “Shaking Foes Hear the High Sonic Boom — It’s in Colbert’s Bat,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1967: 39.

6 John Wilson, “Astros See Bright Future for Bench Kid, Colbert,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1966: 37.

7 Sims.

8 Hano.

9 Hano.

10 Padres360.

11 Paul Cour, ‘Big Colbert Booster: G.M. Leishman,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1970: 11.

12 Padres360.

13 Sarah Wisdom, “San Diego Padres in Yuma — Spring Training 1969,” Yuma County District Library, February 8, 2016. https://yumalibrary.org/san-diego-padres-in-yuma-spring-training-1969/.

14 Padres360.

15 Paul Cour, “Colbert New Power Man for Padres,” The Sporting News, May 17, 1969: 18.

16 Padres360.

17 Paul Cour, “Army Chilled Nate’s Bat,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1969: 35.

18 Paul Cour, “Corkins Winning Battle With Batters and Ulcers,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1970: 28.

19 Paul Cour, “New Padres ‘Snake’ Brings Foes to Knees,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1970: 20.

20 Paul Cour, “Colbert’s Cannon Shots Jolt Padre Foes,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1970: 10.

21 Paul Cour, “Herby Proves Answer to Padre Prayers,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1970: 21.

22 Padres360.

23 Allen Lewis, “Colbert Slams 2 Homers as Padres Best Phils, 8-2,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 8, 1970: 25.

24 Ross Newhan, “Nate Colbert: Name to Remember,” Los Angeles Times, April 12, 1971: 1.

25 Paul Cour, “Barton Relaxes, Starts Belting the Ball,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1971: 16.

26 Newhan.

27 Phil Collier, “Fewer Pounds Lift Colbert’s Stock as Pounder,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1972: 23.

28 Hano.

29 Ibid.

30 Bob Carroll, “Nate Colbert’s Unknown RBI Record,” The National Pastime (2014 reissue), 1982. SABR.

31 Michael Granberry, “Ex-Padre Slugger Nate Colbert Indicted,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1990: B2.

32 Alan Abrahamson, “Colbert Pleads Guilty,” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 1991: C9.

33 Padres360.

Full Name

Nathan Colbert

Born

April 9, 1946 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.