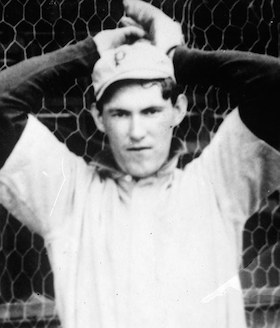

Nick Maddox

Looking back over a century of hometown baseball, a Pittsburgh sportswriter observed that pitcher Nick Maddox “may be the best September call-up in Pirates’ history.”1 No wonder. In his September 13, 1907 major-league debut, the 20-year-old right-hander threw a two-hit, 14-strikeout shutout at the St. Louis Cardinals, winning 4-0. Three days thereafter, he set the Cards down again, 4-2. Later that week, Maddox’s third outing yielded a 2-1 victory over Brooklyn and the first no-hitter ever thrown by a Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher. By season’s end, the recruit’s log stood at 5-1, with only ninth-inning Pirates fielding miscues and a 3-2 loss to Philadelphia standing between Maddox and a perfect slate.

Looking back over a century of hometown baseball, a Pittsburgh sportswriter observed that pitcher Nick Maddox “may be the best September call-up in Pirates’ history.”1 No wonder. In his September 13, 1907 major-league debut, the 20-year-old right-hander threw a two-hit, 14-strikeout shutout at the St. Louis Cardinals, winning 4-0. Three days thereafter, he set the Cards down again, 4-2. Later that week, Maddox’s third outing yielded a 2-1 victory over Brooklyn and the first no-hitter ever thrown by a Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher. By season’s end, the recruit’s log stood at 5-1, with only ninth-inning Pirates fielding miscues and a 3-2 loss to Philadelphia standing between Maddox and a perfect slate.

The following year, Maddox did not disappoint the high expectations created by his September 1907 heroics. Overcoming an early season typhoid scare, Maddox turned in an outstanding 23-8 mark for Pittsburgh. Regrettably, the arm trouble that would short-circuit his major-league career emerged during the 1909 campaign. Although he pitched only intermittently during the regular season, Maddox contributed a gritty complete-game victory to the Pirates’ World Series triumph over Detroit. It was to be his last big-league hurrah. Little used during 1910, Maddox was sent to the minors at the close of the season, his major-league career finished at age 23.

The passage of time and sketchy, sometimes inconsistent, evidence undermine the certitude of any personal history of Nick Maddox. But surviving government documents reasonably establish that our subject was born on November 9, 1886, in Govanstown, Maryland, then a sparsely populated village northeast of Baltimore.2 Nick was born Nicholas Duffy, the name that he would resume using when his baseball days were over. The only things known about his father are his name (John Duffy) and the fact that he was born in Maryland, as was Nick’s mother, whose name and most else about her are completely unknown.3 The events that led to Nick becoming a member of the household of Nicholas and Mary Maddox are likewise unknown. But by the time of the 1900 US Census, Nick was identified as Nicholas Maddox, one of the five Maddox children then present in the home.4 He was raised Catholic, grew up on a Govanstown farm tended by parent-figure Nicholas Maddox Sr., and probably attended school through the eighth grade.5 By 1904 Nick was working as a clerk at a Baltimore drug store, making $6 a week.6

Like countless others, Nick began playing baseball on local sandlots as a youngster. His name first appeared in newsprint when he was a 16-year-old and playing for an amateur club called the Baltimore Bargain House Base Ball Team. On August 11, 1903, the Baltimore American reported that “Maddox pitched and batted well for the BBH club” in an 8-7 victory over the Laurenceville Country Club nine. Nick began building a reputation for himself the following year, playing well for Easton, Lafayette, the Govanstown Athletic Club, and other local amateur teams.7 In 1905 he stepped up a competitive notch, signing with the “strong” Piedmont (West Virginia) club of the semipro Cumberland & George’s Creek League.8 There, he reportedly won “thirty of forty games pitched.”9 That September Maddox was signed by manager Hughie Jennings of the Class A Eastern League Baltimore Orioles and instructed to report immediately.10 But Piedmont refused to release him until its season was completed, resulting in the deferral of Nick’s professional debut to the following season.

Nick Maddox began his professional career in 1906, but not with Baltimore. Rather, he donned the livery of an Eastern League rival, the Providence Grays.11 Listed at a good-sized 6-feet-1 and 173 pounds,12 the now 19-year-old Maddox was primarily a fastball-changeup pitcher. Decades later, he advised his son Jim, a struggling high-school hurler, to concentrate on his fastball and change of pace. “Stick the curve ball in your pocket,” counseled Nick. “Only throw it to let them know you have one.”13 Young Nick Maddox was also a capable lefty batter. But his stay with Providence was brief and unsuccessful. He fared poorly in an early season start against Rochester, and then failed to impress in two subsequent relief appearances. By May 4 Grays manager Jack Dunn had seen enough and released him, the Pawtucket Times opining that Maddox’s “performance in games with Rochester and Buffalo showed that he was not up to Eastern League caliber.”14

After the release, a skirmish between Piedmont and the Cumberland (Maryland) Rooters of the newly formed Class D Pennsylvania-Ohio-Maryland League over Maddox’s services was settled by minor leagues overseer John H. Farrell, who ruled in Cumberland’s favor.15 In short order, Maddox then became “the fastest pitcher in the [POM] league,” going a reported 22-3 for Cumberland.16 In time, news of this phenom reached and interested Pittsburgh Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss. On September 1, 1906, the Pirates acquired the rights to Maddox for the $300 draft price.17

Surprisingly, Pittsburgh did not give Maddox much, if any, of a tryout in 1907 spring camp. Rather, the Pirates released him early to the Wheeling Stogies of the Class B Central League.18 But when Wheeling declined to pay Maddox the $300 a month that he wanted, Nick returned to the POM League, signing with the Uniontown (Pennsylvania) Coal Barons.19 Only the intervention of Pirates boss Dreyfuss defused the looming wrangle between the two clubs. Relying upon a Dreyfuss promise to recall him to Pittsburgh if “he showed speed,” Maddox agreed to suit up for Wheeling.20 Often victimized by poor support from the weak-hitting Stogies, Maddox’s 13-10 record was deceptive, largely camouflaging his dominance of Central League opposition. He threw no-hitters at Grand Rapids and Terre Haute, and allowed only 49 runs in 25 starts for Wheeling. On September 2 a two-hit shutout of Canton witnessed by Dreyfuss himself sealed Maddox’s promotion to the Pirates.21

As noted, Maddox debuted brilliantly for Pittsburgh, shutting out St. Louis on two hits while striking out 14.22 Shortly thereafter, his no-hit effort against Brooklyn – the third no-hitter of Maddox’s 1907 season – was the first no-hitter ever thrown by a Pirates pitcher. And to this day, Nick Maddox, at age 20 years and 10 months, remains the youngest major leaguer to throw a no-hit game from the 60-foot 6-inch pitching distance. In short, he had been very impressive. His six late-season starts, all of which he completed, produced a 5-1 record, with a sparkling 0.83 ERA/0.833 WHIP in 54 innings pitched. He also demonstrated usefulness with the stick, batting a respectable .250 in limited plate appearances. Justifiably, that offseason Pirates brass believed the club possessed a long-term pitching star in young Maddox.

Nick got off to a slow start the following spring, troubled by control problems in exhibition games. Then early in the regular season, he came down with a fever that was first feared to be typhoid.23 Sent home to Baltimore, he recuperated in time to rejoin the club at the end of May.24 And from there, Maddox pitched as if he had never been away. By season’s close he had posted a team-best 23-8 (.742) mark for a 98-56 (.636) Pirates club that dropped out of the memorable 1908 National League pennant chase on the season’s final day.25 Despite the late takeoff, Maddox had managed to log 260⅔ innings, completing 22 of 32 starts. He threw four shutouts, and posted first-rate ERA (2.28) and WHIP (1.147) numbers. The campaign’s only disquieting note had been the low strikeouts (70) and high walks/hit batsmen (a combined 101) totals registered by the hard-throwing righty.

With an everyday lineup that featured future Hall of Famers Honus Wagner and Fred Clarke, plus Deadball standouts Tommy Leach, Chief Wilson, and George Gibson, the 1909 Pittsburgh Pirates were a talented club. And the pitching staff of Nick Maddox, Vic Willis, Howie Camnitz, Lefty Leifield, Deacon Phillippe, Babe Adams, and Sam Leever was positively overstocked with quality arms. Thus, when Maddox suffered a recurrence of spring control problems, there was no pressing need for the club to hand him the ball. Maddox also began to experience throwing pains. He later revealed that “at the beginning of the season, my elbow went out and so did my shoulder. One morning, I found I couldn’t raise my arm.”26 Nick slowly worked himself back into pitching condition, but when he was finally at full strength, Maddox’s availability created a predicament for player-manager Clarke. As expressed by Pirates beat writer A.R. Cratty: “Maddox is ready to work, but others are pitching well. Why break up the combination?”27

Eventually Clarke managed to work Maddox into the rotation, but at season’s close, his respectable 13-8 (.619) mark was the least impressive of any hurler on the 110-42 (.724) National League champions. But tender arms and bad weather afforded Maddox an unexpected pitching opportunity in the ensuing World Series against Detroit. With Game Three to be played in a constant cold drizzle, Clarke scoured the ranks for a hurler able and willing to pitch a big game with a waterlogged ball. At first, he spied no likely candidates. Then Maddox got up and grabbed a baseball. “I’ll handle this wet ball and beat them or break a leg,” he told an appreciative Clarke.28 Facing Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, and a hard-hitting Tigers crew, Maddox labored under miserable pitching conditions and was betrayed by a slipshod Pittsburgh defense that let in five unearned Detroit runs. But in the end, he gutted out a complete-game 8-6 victory, earning the affection and regard of manager Clarke and club boss Dreyfuss in the process. With Babe Adams recording the Pirates’ other three wins, Pittsburgh was the 1909 World Series victor in seven games.

Back home, the locals quickly organized a celebration for their World Series hero. A limousine brought Nick, “his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Nicholas Maddox, his sister Miss Masey [sic, Mary] Maddox,” and other honored guests to “a rousing reception and banquet at the Govanstown Hotel.”29 There, following the requisite toasts and speeches, Maddox was presented with “a handsome gold watch fob in the form of crossed bats and a ball.”30 A brief but heartfelt response was then delivered by the young honoree.

For Nick Maddox, the descent from glory would be swift. But at the time, neither he nor his contemporaries could have realized that. A postseason visit to the renowned Bonesetter Reese was seen as the cure for Maddox’s arm miseries.31 A displaced muscle was reset, leaving the pitcher in an upbeat frame of mind about the coming season. “My wing has been repaired and I am confident of regaining my old form,” said Nick.32 Lamentably, it was not to be. Arm problems returned, reducing Maddox to sporadic and mostly ineffectual duty during 1910. That August, a syndicated news item posed the question: “What’s the matter with Nick Maddox, the clever young twirler of the Pittsburgh Nationals?”33 In the mind of Fred Clarke, the answer was simple: “He ruined his arm helping Adams win the World Series.”34 Paternalistically (and perhaps feeling somewhat responsible for Maddox’s misfortune as well), Clarke resisted the growing call to release Maddox, and carried him on the roster for the remainder of the season. Nick’s final numbers were 2-3, with a 3.40 ERA in 87⅓ innings pitched, not even a shadow of his 23-win performance of only two seasons earlier.

In late September the Pirates sold Maddox’s contract to the Kansas City Blues of the Class A American Association (with the stipulation that Maddox would not have to report until spring camp 1911).35 And with that, his major-league days were over. In an abbreviated career of what-might-have-been, Nick Maddox went 43-20 (.683), with an excellent 2.29 ERA/1.085 WHIP in 605⅓ innings pitched. The only negative stat was his 193 strikeouts to 203 walks/hit batsmen differential. Maddox had also helped himself with the lumber (.244 career batting average) and the leather (.963 fielding average).

Just turned 24 and hopeful of a comeback, Nick readied himself in early spring by going to Washington, DC, and helping Catholic University baseball coach Danny Noonan get his pitching corps in shape.36 He also prevailed before the National Commission on a modest unpaid-salary claim lodged against the Pirates.37 In 1911 Maddox’s 22-13 log in 331 innings pitched for Kansas City seemed proof that his arm was again healthy, and his “great work” prompted late-season speculation that he would be recalled by Pittsburgh.38 But that did not happen. The following campaign saw Maddox back in the American Association, where a 10-13/5.13 ERA effort in a season split between Kansas City and league rival Louisville reflected a pitching career in serious decline. Dropping down to the less competitive Western League in 1913, Nick managed to eke out a winning (11-8, .579) record pitching for a lousy (65-101) Wichita Jobbers club.39 At midseason, he also assumed the managerial reins from the dismissed Charley Babb, becoming the Jobbers’ third field leader during the 1913 campaign.40

The hapless club fared no better under Maddox’s command, but his reviews were favorable. As the season drew to a close, Wichita Beacon sportswriter O.R. Wertz declared, “Manager Maddox has been making good at running the team. … We are back of him in all he attempts. He slipped into the difficult job of running a losing club without a murmur and his good work merits praise.”41 The Denver Post concurred: “There is no fan who can say, truthfully, that Maddox did not make good during the short time he had the club last season. He took charge of the team when it was hopelessly a tail-ender. With the material on hand naturally he did not proceed to win a big majority of the games, but he did get better work out of the team, and he showed good judgment in using the pitchers.”42

Critics were not so kind, however, when Wichita started poorly in 1914. To club observers, Maddox appeared to have lost control of both his players and his self-discipline.43 By late July, the club (37-56, .398) was languishing near the bottom of Western League standings, and Maddox himself (3-13 in 20 outings) was no longer an effective pitcher. On July 22, Wichita gave Nick his unconditional release,44 bringing his tenure in Organized Baseball to a close at age 27.

Maddox promptly returned to Baltimore, where he completed the summer playing semipro ball. For the next seven years, Nick would pitch or play first base for a host of semipro, city league, company league, church league, and amateur baseball teams in the Baltimore area. But by 1917, his gainful occupation was that of streetcar conductor for the United Railway Company, daily traversing the Towson-to-Catonsville route.45 According to his April 1917 World War I draft registration form and the 1920 US Census, Maddox was also now a married man. The identity of his wife is less than certain, but she was most likely a Polish immigrant named Minnie (maiden name unknown, born 1887).46

On September 4, 1921, the Baltimore American reported that Nick Maddox had pitched the Prudential Oil Company club to an 8-0 victory over Baltimore Dry Dock in the city interleague championship series. This is the final discovered instance wherein our subject was identified as Nick Maddox. For the remainder of his life, he would be Nicholas Duffy, the name of his birth. Around 1923 he married Elizabeth Mulligan, a one-time Govanstown neighbor some 16 years his junior.47 Soon thereafter, the couple relocated to the Pittsburgh area, where Nick secured longtime employment as a maintenance man for the Fort Pitt Brewing Company, while Elizabeth gave birth to an infant christened Nicholas Duffy, the first of their nine children. Sadly, Nick’s namesake died while still a boy.48

In June 1941, 38-year-old Elizabeth Mulligan Duffy died of breast cancer, leaving her husband to cope with eight children, aged eight months (David) to 15 years (Edwin). It appears to have been too much for him to manage. In November 1943 a local newspaper reported that “a former Pittsburgh baseball pitcher, Nicholas Duffy of Millvale, better known as ‘Nick Maddox,’ is charged with neglect of his three minor children and has been committed to the county jail on a bench warrant to await a hearing. Duffy, a widower, had failed to appear to answer charges of neighbors that his children were being neglected.”49 The disposition of this family matter was undiscovered by the writer, but Nick apparently remained in charge of his older children; son James Duffy (born 1933) later informed sportswriters that his father had always been around to advise him during his high-school pitching years, and this son, at least, was evidently close to Nick while growing up.50

Our subject was retrieved from obscurity one final time in May 1951 when left-hander Cliff Chambers threw the first Pittsburgh Pirates no-hitter in 44 years – or since Nick Maddox had thrown his for the club. Contacted at home by reporters, Nick was “asked if he hated to see his record bettered. He roared, ‘Hell, no! I was pulling for him. I didn’t hear the game on the radio until the eighth. When I heard he had a no-hitter going for him, I was pulling for him.’”51 Still, he could not resist observing that pitchers were different in his day. “These guys today aren’t pitchers. They’re throwers. Talk about fastballs! Why in my day, I’d throw one so fast past that guy Kiner that he’d get pneumonia from the wind.”52

Retired from the brewery and suffering from tuberculosis, Nicholas Duffy was admitted to Leech Farm Hospital in Pittsburgh in October 1954.53 He died there on November 27, 1954, age 68. Survived by eight children, he was interred in St. Augustine Cemetery, Pittsburgh. The handsome headstone subsequently placed over the grave is inscribed: Nick Maddox Duffy, Pirate Pitcher. First No-Hitter 1907. 1886-1954.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail provided herein include the Nick Maddox player file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Maddox/Duffy family posts on Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Paul Meyer, “September 20, 1907: Nick Maddox Pitched the First No-Hitter in Pirates Franchise History,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 20, 2007.

2 At the time, the names Govans and Govanstown were used interchangeably for the village by both residents and the press. By whichever name, the village was annexed by the City of Baltimore in 1918, and was in the 21st century the site of a distressed urban neighborhood.

3 Informed by son Edwin Duffy, the November 1954 death certificate for Nicholas Duffy, aka Nick Maddox, and entries in the 1920 and 1930 US Censuses provide the little info discovered regarding our subject’s birth parents.

4 A February 9, 2015, post on the Baseball History Daily blog states that “Maddox was born Nicholas Duffy, but adopted his stepfather’s name Maddox.” To the extent that this passage implies that Nick was a child born to Mary Maddox, it is almost certainly wrong. Irish-Catholic immigrant Nicholas Maddox (born c.1850) and his wife Mary (b. 1853) were married in 1881, and began having their seven children the following year. The notion that Maddox family breeding was interrupted in 1886 so that Mary could bear the illegitimate child of someone else is beyond improbable. The notion is further confounded by data provided to 1920 and 1930 US Census takers. According to entries on these records, Nick’s mother was born in Maryland. Mary Maddox was born in England. A more likely possibility is that Nick was a young blood relation of some sort or a neighbor’s child taken in by the Maddoxes after death or other calamity befell his parents. Whatever the case, Nick assumed the surname Maddox as a boy, was treated as a family member by the Maddoxes, and did not resume using his birth name Duffy until the early 1920s.

5 The 1900 US Census has 13-year-old Nicholas Maddox “at school.”

6 As per the 1904 Baltimore City Directory. See also, Sporting Life, April 11, 1908, and the Charlotte Observer, April 18, 1908.

7 As often reported in the Baltimore press. See, e.g., the Baltimore American, June 15, July 16 and 21, August 11, and September 6, 1904, and Baltimore Sun, May 4, and July 13, 1904. Maddox’s 1904 playing accomplishments were later summarized in the Baltimore American, March 9, 1905.

8 As reported by the Baltimore American, March 9, 1905.

9 According to Sporting Life, April 14, 1906.

10 As per Sporting Life, September 25, 1905.

11 Maddox was one of three pitching prospects signed by Providence manager Jack Dunn in the offseason, as per Sporting Life, January 6, 1906.

12 Sporting Life, April 14, 1906. The Baseball-Reference entry for Nick Maddox lists him as 6-feet/175 pounds.

13 Meyer, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 20, 2007.

14 Pawtucket Times, May 5, 1906.

15 As reported in the Baltimore Sun, May 18, 1906. Maddox had signed with Cumberland and then jumped to Piedmont. Farrell forbade any club that was a member of the National Agreement to play Piedmont until Piedmont abandoned its claim to Maddox.

16 As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer, September 1, 1906, and Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 2, 1906.

17 Ibid. See also, Sporting Life, September 8 and 22, 1906, and January 19, 1907.

18 As reported in Sporting Life, March 16, 1907.

19 See the Baltimore Sun, February 20 and March 3, 1907, and Sporting Life, March 16, 1907. Wheeling had threatened to institute action against Cumberland manager Alex Pearson for tampering with Maddox, according to the Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, March 5, 1907.

20 As per Sporting Life, May 8, 1907. Unionville, meanwhile, worked on a possible trade to regain Maddox, according to Sporting Life, April 13, 1907.

21 Dreyfuss’s personal attendance at the game was noted by the Canton (Ohio) Repository, September 2, 1907.

22 The Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times, September 18, 1907, further remarked that Maddox had surmounted the “double-jointed hoodoo of commencing his National League career” on a dread Friday, the 13th.

23 As per the Washington Post, May 21, 1908, and Sporting Life, May 30, 1908.

24 As reported in Sporting Life, May 30, 1908. See also the Cumberland Evening Times, May 26, 1908, and Boston Herald, May 29, 1908..

25 Largely as a result of the infamous Merkle boner, the Chicago Cubs and New York Giants had tied for first place at season’s end with 98-57 records. The Cubs then won the 1908 NL pennant by defeating New York in a one-game playoff.

26 Baltimore American, February 21, 1910.

27 Sporting Life, July 31, 1909.

28 As later recalled by manager Clarke in explaining his fondness for Maddox. See the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times, November 6, 1912.

29 Baltimore Sun, October 27, 1909.

30 Ibid.

31 See Sporting Life, October 30, 1909, and the New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, March 14, 1910. Neuralgia or rheumatism was diagnosed as the underlying problem.

32 Baltimore Sun, February 21, 1910.

33 See, e.g., the Charlotte Observer and Canton Repository, August 14, 1910, and Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, August 21, 1910.

34 August 1910 Pittsburgh Gazette-Times article quoted in Baseball Daily History, February 9, 2015.

35 As reported in the Indianapolis Star and Washington Post, September 27, 1910.

36 As reported in the Washington Post, December 18, 1910.

37 As noted in the Baltimore Sun, December 14, 1910. When Maddox’s contract was sold to Kansas City in late September, Pittsburgh removed him from the club payroll, Because the Kansas City season was over by then, his new club declined to pay Maddox for the final two weeks covered by his Pittsburgh contract (which ran to October 15). In a precedent-setting ruling thereafter known as the Maddox Decision, the National Commission determined that Pittsburgh was on the hook for the unpaid wages sought by Maddox. A fuller explanation of the matter is provided in Sporting Life, January 14, 1911.

38 As reported in Sporting Life, September 11, 1911, and the Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, September 19, 1911. See also the Adams County (Pennsylvania) News, January 11, 1912.

39 Baseball-Reference has no 1913 won-lost record for Maddox. The 11-8 record comes from final Western League stats published in the Denver Post, October 12, 1913.

40 As reported in the Denver Rocky Mountain News and (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette, July 30, 1913, and Duluth News-Tribune, July 31, 1913. Maddox replaced Babb who in May had replaced George Hughes, the Jobbers’ initial 1913 manager.

41 As reprinted in the Kansas City Star, September 23, 1913.

42 Denver Post, January 17, 1914.

43 According to the Omaha World-Herald sports column “Vandy’s Dope,” July 27, 1914.

44 As reported in the Denver Post, July 22, 1914, and Philadelphia Inquirer and San Francisco Chronicle, July 23, 1914.

45 As per the World War I draft registration form signed by Nicholas Maddox in April 1917. His occupation as a streetcar conductor had previously been noted in the press. See, e.g., the (Boise) Idaho Statesman, January 14, 1917, and Evansville Courier and Press, January 19, 1917.

46 As reflected in the 1920 US Census.

47 The fate of Nick’s union with Minnie Maddox is unknown. But she appears in the 1937 Baltimore City Directory as “Minnie Maddox (widow of Nicholas).” At the time, “widow” was a marital status often provided by women in order to avoid the stigma of divorce or abandonment.

48 According to his death certificate, son Nicholas Duffy died from acute hepatitis on January 30, 1935, just short of his11th birthday. The next male child born to Nicholas and Elizabeth Duffy after the death of young Nicholas was named Nicholas Joseph Duffy.

49 Charleroi (Pennsylvania) Mail, November 19, 1943. The three youngest Duffy children would have been Kathleen (born 1938), Nicholas Joseph (1939), and David (1940). The article also made mention of the 1907 no-hitter and the 1909 World Series victory posted by their father.

50 See again, Meyer, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 20, 2007.

51 As reported in the Boston Herald and The (Portland) Oregonian, May 7, 1951.

52 As per Meyer, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 20, 2007.

53 The institution’s rarely used official name was the Pittsburgh City Tuberculosis Sanitarium.

Full Name

Nicholas Maddox (Duffy)

Born

November 9, 1886 at Govanstown, MD (USA)

Died

November 27, 1954 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.