Pat Newnam

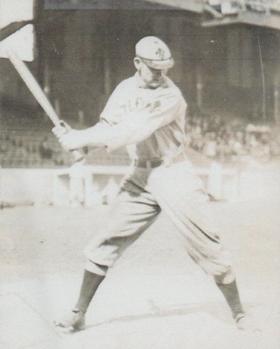

Apart from a lackluster stint with the 1910-1911 St. Louis Browns, first baseman Pat Newnam spent his long professional career in the minor leagues, mostly in his native Texas. His principal shortcoming as a player was a common one: marginal ability. The righty batting and throwing Newnam had good size (6-feet, 180 pounds), exceptional foot speed, and occasional long-ball pop in his bat. But for the most part, he was no better than a mediocre hitter and fielder, even at the mid-minor-league level. The respect that Newnam gathered over two decades as a Texas League player and manager rested upon intangibles: keen baseball intelligence, leadership abilities, and, most notably, a fierce competitive spirit, sprinkled with a penchant for mayhem. He once floored New York Giants manager John McGraw with a sucker punch, and was known as a man who “always ran toward, rather than away from, a fight.”1 Indeed, at the time of his passing in 1938, Pat Newnam was remembered as “one of the fightingest Irishmen in baseball.”2

Apart from a lackluster stint with the 1910-1911 St. Louis Browns, first baseman Pat Newnam spent his long professional career in the minor leagues, mostly in his native Texas. His principal shortcoming as a player was a common one: marginal ability. The righty batting and throwing Newnam had good size (6-feet, 180 pounds), exceptional foot speed, and occasional long-ball pop in his bat. But for the most part, he was no better than a mediocre hitter and fielder, even at the mid-minor-league level. The respect that Newnam gathered over two decades as a Texas League player and manager rested upon intangibles: keen baseball intelligence, leadership abilities, and, most notably, a fierce competitive spirit, sprinkled with a penchant for mayhem. He once floored New York Giants manager John McGraw with a sucker punch, and was known as a man who “always ran toward, rather than away from, a fight.”1 Indeed, at the time of his passing in 1938, Pat Newnam was remembered as “one of the fightingest Irishmen in baseball.”2

Christened Robert Albert Newnam, our subject was born on December 10, 1880, in Hempstead, Texas, a sleepy town some 50 miles northwest of Houston. He was one of nine children born to printer and spiritualist Charles Newnam (1837-1924) and his wife, Frances (née Farr, 1844-1923), both Missouri natives. Little is known regarding his early years, including when and how he got the nickname Pat.3 The available evidence indicates that the Newnam family relocated to San Antonio when Pat was still a child, and that he resided there for the remainder of his life.4

In his youth Pat attended local schools through graduation from San Antonio High School, and then entered the local work force.5 Newnam began playing baseball on city sandlots as a boy. Thereafter, he and best-friend Lou Barbour (years later traveling secretary for the Chicago White Sox) organized the Tobin Hill Reds, a neighborhood amateur nine.6 In 1900 he joined the Katy (or I.&G.N.) Reds of the fast San Antonio City League. Pat entered the professional ranks in 1903, signing with the hometown San Antonio Bronchos of the newly formed Class C South Texas League. Installed at first base – the only position that he would ever play as a pro7 – Newnam got off well, batting .274 with 13 home runs, for the pennant-winning Bronchos. That year he also commenced a 35-year marriage to fellow San Antonian Grace Agnes Gillespie (1884-1968), the daughter of an Irish Catholic immigrant father and descended from a Confederate Army cavalryman on her mother’s side. The birth of son Robert Connell Newnam in 1913 would complete the family.

The budding baseball career of Pat Newnam stalled in 1904. Plagued by early-season arm miseries, he was cut by San Antonio in April,8 and thereafter declined an offer to play with a league rival, the Galveston Sand Crabs. According to Galveston manager Marcene Johnson, Newnam wanted to avoid further public exposure of his throwing problems.9 He therefore spent the season playing and managing an independent nine in out-of-the-way Victoria, Texas.10 Newnam got a fresh start the following year, signing with the Charleston Sea Gulls of the Class C South Atlantic League.11 But after he had batted a meager .203 in 43 games, Charleston released him.12 Pat then returned home, where he once again became a San Antonio Broncho.13 In a harbinger of things to come, Newnam promptly got himself suspended by South Texas League President Bliss Gorham for punching a Houston Buffalo baserunner in the mouth. The incident also gave rise to an assault conviction in the local Justice Court. The sentence imposed on Newnam: $5 fine, plus court costs.14

In 1906 Pat began the first of several tours of duty with the Houston Buffalos, then another member of the South Texas League. By season’s end, he had posted solid, if unspectacular, offensive numbers (.261 BA, with the 40 extra-base hits) and played a tolerable first base. But the campaign was punctuated by another trip to court, this one falling into the bizarre-but-true category. In late June, District Court Judge Charles E. Ashe entered an injunction that prohibited Newnam from taking the coaching lines for the Lean Men’s Baseball Team in an upcoming exhibition game against the Fat Men’s nine. In its wisdom, the court concluded that the 180-pound Newnam “was not of light enough weight to be used on the thin team,” and directed that he “should remain an impartial spectator” during the contest. And the court’s order was no joke. As noted with regret by the Houston Chronicle, the proceedings had been conducted in dead earnest, with both sides “being represented by the very best legal talent in Houston.”15

In 1907 the Houston, San Antonio, and Galveston clubs joined the reconstituted Class C Texas League. By doing so, two hallmarks of Pat Newnam’s baseball career were enabled: (1) longtime association with the Texas League, and (2) managing at the professional level. But Pat began the season far from Texas, having signed over the winter with the Portland Beavers of the Class A Pacific Coast League. But 15 games into the season, Newnam dislocated his shoulder, whereupon Portland released him.16 Upon his return home, he once again donned the livery of the San Antonio Bronchos, now managed by infielder Sam LaRocque. That changed after a doubleheader against the Austin Senators on July 23. Game 1 featured Pat Newnam, irate with an out-at-third call, being removed from the grounds under police escort. After another bad umpiring decision, the rest of the Bronchos walked off the field, resulting in a forfeit. The San Antonio players retook the diamond for Game 2, if only to reduce the contest to a farce. Final score: Austin 44, San Antonio 0.17 Unamused Texas League President William Robbie fined manager LaRocque $50, which LaRocque refused to pay. Instead, he resigned his position as manager. To fill the void for the remainder of the season, Bronchos boss Morris Block appointed first baseman Newnam playing manager,18 thus initiating Pat’s maiden tenure at the helm of a Texas League club. He brought the club in as a respectable (82-58) third-place finisher.

The following spring, Newnam surrendered the managerial reins to outfielder George Leidy and focused solely on being the Bronchos’ first baseman. But with San Antonio clinging to a slim first-place lead in mid-August, “peevish antics” by manager Leidy cost the team an important game against Fort Worth.19 Displeased club owner Block promptly fired Leidy and reinstalled Newnam at the helm. The move paid handsome dividends, as Pat then steered the Bronchos to their first Texas League flag. Newnam himself had been a significant contributor to the triumph, batting .283 with 44 extra-base hits for the (95-48) pennant winners. But when he and Block could not reach agreeable terms on renewal of his contract, Pat signed a player-only pact with Houston. The Buffalos won the Texas League pennant in 1909, and Newnam was again a significant contributor (.288 BA, with 35 extra-base hits) to the title effort. At this point, however, Newnam did not appear to be a major-league prospect. Rather, he was a reliable 28-year-old journeyman in a mid-level (Class C) minor-league circuit. But happily for Pat, the events necessary to give him an unlikely major-league shot had begun to unfold.

A key component in Newnam’s elevation to the majors was the rottenness of the St. Louis Browns, a seventh-place (61-89) finisher in the 1909 American League standings. At season’s end, dissatisfied club owner Robert Hedges fired manager Jimmy McAleer, replacing him with former Browns catcher Jack O’Connor. Hedges also went on the lookout for new playing talent. Enter Pat Newnam, brought to Hedges’ attention by local admirers while the Browns conducted their 1910 spring camp in Houston. Intrigued by the “wonderfully fast time” posted by Newnam in a club-sponsored track and field meet, Hedges acquired the rights to his services.20 But for the time being, the Browns first-base job was intended for Bill Abstein, just purchased from the world champion Pittsburgh Pirates. Optioned back to Houston, Newnam picked a most opportune time to have the lone torrid batting streak of his professional career. In 38 games he batted .350 for the Buffalos. Meanwhile back in St. Louis, Abstein had been a complete bust, both at bat (.149 BA) and in the field (11 errors in 23 games). With the Browns stuck in the AL cellar, Hedges sold Abstein to a minor-league club and exercised his option on Newnam.21

On May 29, 1910, now-29-year-old Pat Newnam made his major-league debut in a 13-4 home loss to Detroit. Newnam’s individual performance was mixed. Facing Tigers right-hander Ed Summers, his foot speed allowed him to scratch out two infield singles in four at-bats. His work in the field was another matter. Newnam was charged with two errors in 17 chances, and failed to make several other plays. But the volume of blistering shots sent his way by Tiger batsmen was taken into consideration by the press. A sympathetic St. Louis Republic observed that the club’s new first baseman “was almost burned to death by liners, grounders, wild throws, low throws, high flies, and mailed feet. The Detroiters made nineteen hits and it seemed that all of them were aimed at Newnam.”22 And back in Texas, Newnam’s defensive work was portrayed as absolutely heroic, with Pat standing tall against “a vigorous attack by the Detroits. They slashed and hammered at the big fellow … until he was a mass of cuts and bruises. They lacerated his feelings and his flesh, but they couldn’t drive him from the job.”23

Six weeks into his Browns tenure, Newnam’s batting average hovered in the Deadball Era-respectable .280s. By then, local critics had long since declared their views on Pat’s abilities, with opinions sharply divided. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat was a booster, praising, in particular, the newcomer’s aggressiveness: “A few more players of the Newnam kind and the [Browns] might possibly win a few more games.”24 The Sporting News, the St. Louis-based house organ of major-league baseball, was in the other camp, opining that “Pat Newnam is not of big leagues timber and will soon be back with brush [sic] league teams.”25 Of far more immediate consequence, Browns manager O’Connor was among those unimpressed with Newnam. Shortly after Newnam’s debut, the club’s signing of touted New York semipro first baseman Joe Higgins led to widespread prediction that Newnam would soon be dispatched to the minors.26 But Higgins never played a game for St. Louis, and Newnam, although his hitting had begun to decline, hung on as the Browns first baseman. That came to an end in mid-September with the Browns limping toward a woeful last-place (47-107) finish. During a by-now meaningless game against Cleveland, Newnam mishandled a pickoff throw from pitcher Joe Lake and then loafed retrieving the ball, allowing the runner to reach third. That was the final straw for O’Connor, who immediately suspended Newnam for the remainder of the season.27 At the time, he was seen as no great loss; Pat’s batting average had slid to .216, with only 13 extra-base hits and 26 RBIs in 103 games. He had also made 32 errors in the field.

As far as O’Connor was concerned, the underperforming Newnam, whom he also branded a “disorganizer” in the Browns clubhouse, was finished in St. Louis.28 Home in San Antonio, Pat responded in kind, stating that he would “quit organized base ball before he will ever don another uniform for St. Louis as long as O’Connor is boss.”29 The matter seemed largely moot – until an official league inquiry was undertaken into the Browns’ defensive strategy against Cleveland’s Nap Lajoie during a final-day doubleheader. O’Connor’s distant placement of rookie third baseman Red Corriden whenever Lajoie came to bat was decidedly peculiar, and guaranteed the well-liked Frenchman, then in a corset-tight battle for the AL batting title with the widely reviled Ty Cobb, a slew of bunt base hits. At the conclusion of the inquiry, O’Connor’s conduct was deemed a stain upon the integrity the batting race, one that warranted his banishment from Organized Baseball.30

An incidental effect of O’Connor’s disgrace was the revival of Pat Newnam’s fortunes in St. Louis. Club owner Hedges informed the press that he saw “no reason why Newnam should not come back [to the Browns]. I hold nothing against him and as for any trouble with O’Connor, I don’t think that will be carried over, but Pat will be called to return.”31 Another thing working in Newnam’s favor was the identity of the new St. Louis Browns manager: future Hall of Famer Bobby Wallace, the club’s veteran shortstop and a teammate kindly disposed toward Pat. When the 1911 season began, Newnam had been restored as the Browns’ regular first baseman.32 Sadly, he proved unable to hold the job. In 20 early-season games, Pat went 12-for-62 (.194), with little power (four extra-base hits and only five RBIs). His defensive work was also substandard. On May 15, 1911, Newnam was sold to Houston,33 bringing his major-league days to an end in just under one year’s time.

Truth be told, Pat Newnam simply lacked the talent required for an extended major-league playing career. A century later, Newnam is remembered, if at all, for his post-major-league exploits. His return to Houston got off to a rocky start. In June a salary dispute with club management prompted a loud but empty threat by Newnam to quit baseball.34 Then at season’s end, Pat was among seven Buffalos players fined $250 and suspended indefinitely for refusal to accompany the club on the road for its final games.35 In time, however, Pat and club brass reconciled their differences, and he remained a useful, if now weaker-batting, member of the Houston clubs that captured back-to-back pennants in the now-Class B Texas League of 1912-1913.

Despite having piloted the Buffalos to consecutive league titles, Houston manager-second baseman Johnny Fillman was not rehired for the 1914 season. Instead, the post went to Newnam.36 The stage was now set for Pat Newnam’s 15 minutes of fame – or infamy. To finish spring training camp, manager John McGraw brought the defending National League champion New York Giants to Houston for a four-game set against the Buffalos. In the third contest, Newnam tangled with Giants outfielder Fred Snodgrass after a collision around first base. This, in turn, precipitated heckling about “bush leaguers” from McGraw, gibes that former big leaguer Newnam deeply resented but suffered in silence, at least for the time being. After intersquad practice the following morning, McGraw led his charges toward a ballpark exit. No words were exchanged when the group walked toward a gathering of Houston players, but as they passed Newnam unleashed a haymaker at McGraw. The punch caught the unwary Giants skipper square in the mouth, splitting his lip and temporarily knocking him cold. New York shortstop Art Fletcher then returned the favor, his overhand right sending Newnam sprawling. But the incident was over in a flash, as the groups separated and Giants players hustled to get the bleeding McGraw back to their hotel. There, McGraw made a speedy recovery and was back at the ballpark in time for afternoon practice.37

The incident received attention in newspapers nationwide, with most commentary condemning Newnam for a cowardly sneak attack on an older, much smaller man. Buffalos’ management was also angry with Newnam, as his assault of McGraw had come at a particularly infelicitous time. Unbeknownst to Pat, club brass had been in private negotiation with McGraw about his acquiring an interest in the Houston franchise. Based upon a “thorough investigation of the deplorable affair” commenced and completed within hours, Houston co-owners Otto Sens and Doak Roberts telegrammed their apologies to McGraw, and suspended Newnam indefinitely.38 But once McGraw was safely back in Gotham, the suspension was lifted, just in time for manager Newnam to guide the Buffalos on Opening Day.39

Under Newnam’s direction, the Houston Buffalos finished first in Texas League standings for a third consecutive time, one game better than the runner-up Waco Navigators. Or so it seemed at the end of the season. But weeks later, minor leagues overseer John H. Farrell’s resolution of a dizzying array of game protests and other complaints left Houston and Waco with identical 102-50 records. Too late to conduct a pennant-deciding playoff, the two clubs were officially declared joint Texas League champions of 1914.40

Pat Newnam continued at the Houston helm for another four seasons, but was unable to repeat his 1914 success. From 1915 through 1918, the Buffalos finished no higher than fourth in the Texas League standings. During this period, however, Newnam was able to improve his fisticuffs record. In July 1917 he registered a TKO victory over umpire Paul Sentell in a private, prearranged fight to settle their on-field differences. The much taller Newnam peppered Sentell with jabs, and then jarred him with several hard right-crosses. The umpire was still game but his second threw in the towel.41 The two combatants then shook hands, their disagreements settled. The following July, it was Newnam throwing in the towel. After a dispute with club boss Doak Roberts and with his 38-46 club mired in fifth place, Pat resigned as Houston manager.42 Two days later, the Texas League suspended operations for the duration of World War I.

Removed from the baseball scene, Newnam gave full-time attention to his offseason occupation of used-car salesman. He specialized in buying and selling second-hand Fords.43 But not long after the war ended, Pat was back in harness as field leader of another Texas League club, the Beaumont Exporters. With its 40-year-old player-manager providing negligible help (.195 BA in 16 games), the 64-93 Exporters were distant seventh-place finishers in the 1921 league standings. Newnam’s discharge at season’s end brought a 16-season professional playing career to an end. While only a .262 lifetime minor-league batter, Newnam’s longevity permitted him to establish various combined South Texas-Texas League records. At the time of his death almost 20 years later, Pat was still the all-time league leader in games played; runs scored; extra-base hits; total bases; and sacrifices, among other firsts.44

Although his playing days were now behind him, Newnam remained in uniform. Hired as an assistant to Galveston Sand Crabs manager Dave Griffith in 1922, Pat took the club reins when Griffith resigned in June.45 He quickly rallied the Sand Crabs from well back in the pack to atop the league standings, before settling for a fourth-place (79-76) finish. No such luck the following year: The Newnam-led Galveston club (68-80) was a nonfactor in the 1923 Texas League pennant chase. Released, Pat then embarked upon an improbable stint as a Texas League umpire. He lasted until August before quitting. Newnam then went back to selling used Fords. He also purchased a half-interest in the Alamo Club, a San Antonio gaming den that Pat proposed to convert into an upscale gentlemen’s club.46

Newnam’s separation from baseball lasted until early 1926, when he accepted appointment as president-business manager of the six-club Class D Gulf Coast League. The following two years, he served as chief executive of another Class D circuit, the Lone Star (or Texas Valley) League. Pat concluded his long run in professional baseball with one last turn in the Texas League, assuming midyear command of the San Antonio Indians. A last-place (56-106) San Antonio finish brought an inglorious end to a generally competent minor-league managing career.

Pat Newnam spent the final years of his working life as founder-operator of the San Antonio Novelty Amusement Company, purveyor of gumball machines, jukeboxes, and other entertainment industry equipment. His handling of slot machines, however, produced intermittent (but usually inconclusive) skirmishes with local anti-vice police and gambling regulatory authorities.47 In early 1938, Pat’s health went into irreversible decline from the effects of tuberculosis. Confined to bed in his last months, Robert Albert “Pat” Newnam died at home on June 20, 1938. He was 57. Funeral services conducted at the Newnam residence were followed by interment at St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, San Antonio. Survivors included his wife, Grace; son, Robert; and older brothers Charles, Joseph, and Frank Newnam.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail provided herein include the Pat Newnam file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Newnam family info posted on Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited below, particularly memory lane-type columns authored in the 1930s by longtime San Antonio Express sports columnist Fred Mosebeck. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, June 30, 1938.

2 Dallas Morning News, June 21, 1938. In passing, however, it might be noted that Newnam is not a common Irish surname, and the basis for the widespread belief that Pat was of Irish descent went undiscovered by the writer.

3 However he came by the nickname, our subject was known as Pat Newnam his entire adult life. But wife Grace, long active in San Antonio social and civic affairs, was invariably identified in newsprint as Mrs. Robert Newnam.

4 As reflected in US Census reports and San Antonio city directories.

5 Reminiscences of Pat Newnam and classmate Lou Barbour published decades later refer to their alma mater as Main Avenue High School, the name bestowed on the institution after its reconstruction in 1917.

6 Most of the detail regarding Newnam’s early baseball days has been drawn from columns authored by San Antonio baseball historian and sportswriter Fred Mosebeck. See, e.g., “Rounding Up the Sports,” San Antonio Express, October 14, 1929, February 4, 1930, December 22, 1931, March 27, 1932, February 11, 1934, and March 8, 1936.

7 Although right-handed, fleet-footed, and athletic, there is, oddly, no record of Newnam’s playing as much as one game in the outfield, or at any position other than first base, during his professional career.

8 As reported in the San Antonio Gazette, April 12, 1904.

9 As per the Galveston Daily News, May 7, 1904.

10 As noted by the San Antonio Gazette, April 12, 1904, and later by Fred Mosebeck in various of his columns.

11 Newnam’s signing with Charleston was reported in Sporting Life, February 25, 1905. Note: Until he reached the major leagues in May 1910, Sporting Life gave our subject’s surname as Newman.

12 As reported in Sporting Life, July 8, 1905.

13 According to Baseball-Reference, Newnam also spent time with the Charlotte Hornets of the Class D Virginia-North Carolina League in 1905. The writer, however, was unable to find substantiation of a tour of duty by Newnam with Charlotte.

14 As reported in the San Antonio Express, July 7, 1905. The Newnam suspension from South Texas League play was lifted days thereafter.

15 See the Houston Chronicle, June 28, 1906, which also took note of the “considerable time and money spent in arguing the case” and “the depth of feeling that is being displayed by the members of the two teams.”

16 As per the San Antonio Gazette, April 25, 1907, and Sporting Life, May 18, 1907.

17 The antics of Bronchos players during the second game were sketched in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Houston Chronicle, July 24, 1907.

18 As reported in the Houston Chronicle, July 31, 1907.

19 According to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 18, 1908.

20 See Sporting Life, March 5, 1910.

21 As reported the Dallas Morning News, May 19, 1910. The cost of Hedges’ reacquisition of Newnam varied in newsprint. See, e.g., the Dallas Morning News, May 29, 1910 ($3,000); Sporting Life, August 13, 1910 ($1,200).

22 St. Louis Republic, May 30, 1910.

23 See “Tigers Seek Goat of Our Pat Newnam in Opening Game,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 1, 1910.

24 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 2, 1910.

25 The Sporting News, June 9, 1910.

26 See, e.g., the Muskegon (Michigan) Chronicle, June 11, 1910, Dallas Morning News, June 12, 1910, and Daily (Springfield) Illinois State Register, June 15, 1910.

27 As reported in the Washington Evening Star, September 15, 1910, and Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 16, 1910.

28 As reported in the Washington Evening Star, September 24, 1910.

29 Washington Evening Star, September 26, 1910.

30 For a thorough account of the matter, see Rick Huhn, The Chalmers Race: Ty Cobb, Napoleon Lajoie, and the Controversial 1910 Batting Title That Became a National Obsession (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

31 Houston Chronicle, November 6, 1910.

32 As reported in Sporting Life, March 25, 1911, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 9, 1911, and Houston Chronicle, April 11, 1911.

33 As reported in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 15, 1911, and Sporting Life, May 27, 1911.

34 As per the Houston Chronicle, June 14, 1911.

35 As reported in the Dallas Morning News and Houston Chronicle, November 18, 1911.

36 As reported in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Houston Chronicle, January 25, 1914.

37 The event was reported nationwide. See, e.g., the Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, New York Times, and Rockford (Illinois) Republic, April 1, 1914. See also, Houston Baseball: The Early Years, 1861-1961, Mike Vance, ed. (Houston: Bright Sky Press, 2015), 330.

38 As per the Tulsa World, April 2, 1914. See also, the Houston Chronicle, April 1 and 2, 1914.

39 As reported in the Houston Chronicle, April 8, 1914.

40 As explained in the 1915 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 193.

41 As reported in the Houston Chronicle, July 2, 1917. It was later revealed that Newnam had injured his right hand on Sentell’s head.

42 As reported in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 5, 1918.

43 Advertisements for “Pat Newnam Used Car Bargains” were regularly published in local newspapers. See, e.g., the San Antonio Express, October 19, 1922, and San Antonio Evening News, November 16, 1922.

44 As noted in Newnam’s obituaries published in the Dallas Morning News and San Antonio Light, June 21, 1938, and The Sporting News, June 30, 1938.

45 As reported in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Galveston Daily News, June 17, 1922.

46 As reported in the San Antonio Light, October 12, 1924.

47 An attempt by authorities at criminal prosecution via unlawful possession of gambling device-type charges was thwarted when a Bexar (San Antonio) County grand jury declined to return an indictment against Newnam, as reported in the San Antonio Express, January 1, 1933.

Full Name

Robert Albert Newnam

Born

December 10, 1880 at Hempstead, TX (USA)

Died

June 20, 1938 at San Antonio, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.