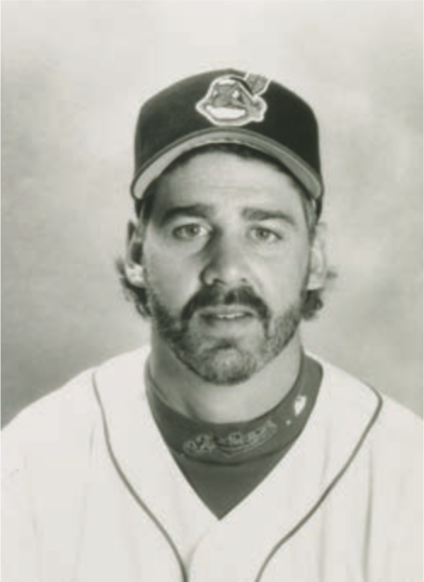

Paul Assenmacher

Detroit native Paul Andre Assenmacher (born December 10, 1960) epitomized the somewhat obscure baseball term LOOGY (Lefty One-Out Guy) by making a “long and profitable career out of coming into a game, pitching to one or two left-handed batters, then leaving.”1

Detroit native Paul Andre Assenmacher (born December 10, 1960) epitomized the somewhat obscure baseball term LOOGY (Lefty One-Out Guy) by making a “long and profitable career out of coming into a game, pitching to one or two left-handed batters, then leaving.”1

Assenmacher, who pitched for the Aquinas College Saints (Grand Rapids) from 1981 to 1983, still held a few school records as of 2017, including most innings pitched in a season (98 in 1983), most strikeouts in a season (123 in 1981), and tied for most strikeouts in a career (246). Aquinas went 125-57 (.687) during his time there. Coming from a small school, his college stats were not enough to get him drafted, but the Atlanta Braves in 1983 signed him as an undrafted free agent. At the Braves’ Gulf Coast League (Rookie) affiliate for the remainder of the season, Assenmacher teamed with future Braves Ron Gant and Mark Lemke, and future national champion football coach Urban Meyer. He pitched in 10 games, including three starts. He was 1-0, with a 2.21 ERA. Even more impressive, considering he was not a starter, was that he led the team with 44 strikeouts.

Assenmacher spent 1984 with the Durham Bulls (Class A Carolina League). He made 24 starts, going 6-11 with a 4.28 ERA, but his peripherals were good. He led all starters with a 2.83 K/BB ratio and struck out 147 batters, second highest on the team.

Assenmacher started the 1985 season back in Durham, this time pitching only out of the bullpen. This earned him a promotion to Greenville of the Double-A Southern League. As in Durham, he pitched solely out of the bullpen. He had a 6-0 record with a 2.56 ERA, and his peripheral numbers showed improvement too. He did not give up a home run in his 52⅔ innings of work. Assenmacher was viewed as one of the future arms for the Braves. His presence helped the Braves decide to not bring back veteran Phil Niekro.2

Assenmacher was invited to big-league spring training in 1986, and made the club. He did not disappoint, appearing in 61 games, all out of the bullpen, and ended with a 7-3 record with a 2.50 ERA. He was a bright spot for the last-place Braves, who had one of the worst pitching staffs in the National League. The strong performance garnered interest around the league, including some discussions with the Indians involving Brett Butler,3 but the Braves elected to hang on to their young lefty.

For Assenmacher, 1987 was a rough year. While pitching on the worst staff in the National League, he had arguably his worst year as a professional. His ERA went up over 5.00. Assenmacher was still in demand; the Mets and Braves discussed a potential deal involving him and Mets outfielder Mookie Wilson, but a deal never materialized.4

In 1988, the lefty bounced back, with an 8-7 record and a 3.06 ERA in 64 games. His Other statistics also improved. Before the 1989 season, he sought a raise to $200,000, while the Braves offered $170, 000.5 Eventually, Assenmacher agreed to a contract for $181,000.6 His 1989 season was even better, with an improved strikeout-to-walk ratio. On August 22 against St. Louis, Assenmacher faced five batters, striking out four. Two days later, the Braves traded him to the Chicago Cubs. The Cubs were in a race for the crown in the NL East, but Assenmacher did not provide the stability they were looking for. He had a dreadful September and October, including two appearances of a third of an inning each in Games Two and Three of the National League Championship Series against the San Francisco Giants (despite carrying a four-leaf clover in his back pocket during the playoffs7). His ERA was almost 6.50, and his strikeout-to-walk ratio dipped drastically in the final two months of the regular season.

The 1990 Cubs were a disappointment on the field, finishing 77-85, but Assenmacher was steady. He was the team’s best pitcher out of the bullpen, going 7-2 with a 2.80 ERA. He pitched a career-high 103 innings, and made his first professional start since 1987, and the only start in his major-league career. He lasted only one inning and gave up four earned runs. Over the entire season, though, Assenmacher held left-handed batters to a .223 batting average.

Before the 1991 season, the Cubs went after Royals starter Kevin Appier with a package involving first baseman Mark Grace.8 When that fell through, the Cubs turned to strengthening their bullpen by signing Assenmacher (who was in his walk year) to a three-year, $7 million deal (or $7.5 million, depending on the source9), with a club option for a fourth year.10 Assenmacher responded by achieving career bests in games and strikeouts. His 102⅔ innings pitched were the most for NL relievers; he was second in the league in strikeouts and games pitched. The Cubs figured they would lose Assenmacher to free agency after 1992 since he had drawn so much interest during the season, and left him unprotected in the 1992 expansion draft, when Colorado and Florida joined the league. But he went unclaimed by either franchise.11

Assenmacher was traded to the New York Yankees in a three-team deal before the 1993 non-waivers trade deadline. The Cubs picked up minor-league power hitter Karl “Tuffy” Rhodes. Rhodes would later be known as the first player to hit a home run in his first three at-bats on Opening Day when he did it for the 1994 Cubs.

During spring training in 1994, Assenmacher was dealt to the Chicago White Sox for minor-league pitcher Brian Boehringer. The Yankees saved money but also created a roster spot for one of their prospects, Sterling Hitchcock. At the time, the Yankees had a decent bullpen; Assenmacher figured he was the one traded because “my name was pulled out of a hat.”12 The trade was important to the White Sox, considering that they were favored by many to win the AL Central crown. Over the strike-shortened season, Assenmacher held left-handers to a .196 batting average, but he was still waived at the end of the season.

Assenmacher signed as a free agent with the Cleveland Indians in April 1995 for $700,000, with another $200,000 in performance bonuses.13 This signing was delayed because of the strike that canceled the 1994 World Series. The signing paid immediate and long-term dividends. The Indians won the AL Central five years in a row, and Assenmacher became an important part of the bullpen as a left-handed specialist.14 He pitched in 47 games in 1995, holding lefties to a .188 batting average and .235 on-base percentage. This helped the Indians make their first postseason appearance and first World Series appearance since 1954, when they were swept in four games by the New York Giants. Assenmacher earned a hold the night the Indians clinched the division, September 8, 1995.

The Indians had the best record in baseball entering the playoffs (100-44), but never had home-field advantage. The 1995 season was the first year of the wild-card format for the playoffs. At that time, home-field advantage rotated among the division leaders. This would be the AL East and the AL West champions, Boston and Seattle respectively. Playoff rules also said that the wild-card team could not play a team in its own division in the division round, but it could not have home-field advantage either. If the Yankees had played the Indians, the Yankees would have had home-field advantage. Instead, the Yankees opposed Seattle, and the Indians faced the Red Sox.15

Assenmacher pitched in all three games of the sweep over the Red Sox for a total of 1⅔ innings, without giving up a run. The Indians faced the Mariners in the ALCS, and won the series, 4-2. Assenmacher pitched 1⅓ innings, without giving up a run. Perhaps his most important outing of the ALCS was Game Five. He entered the game with runners at first and third with only one out, thanks to back-to-back errors by Indians first baseman Paul Sorrento. Assenmacher got Ken Griffey Jr. to strike out swinging. Manager Mike Hargrove left Assenmacher in to face the right-handed-hitting Jay Buhner. Buhner had hit .458 against the Yankees and was hitting .389 in the ALCS up until that point. Buhner struck out on a 2-and-2 breaking ball, surprising almost everyone.

Assenmacher overall had a decent World Series, except for one pitch. Atlanta was leading the Series two games to one, heading into Game Four at Jacobs Field in Cleveland. The Braves were up 2-1 in the game, when Assenmacher entered in the top of the seventh with one out. Indians starter Ken Hill had given up a run on Luis Polonia’s double. Assenmacher issued an intentional walk to his first batter, Chipper Jones, putting runners at first and second. A passed ball allowed the runners to advance, then Assenmacher struck out Braves slugger Fred McGriff. Assenmacher worked a 1-and-2 count to David Justice, and tried to get Justice to bite on a curve. Instead, the curve stayed in the middle of the plate, and Justice singled to drive in two runs.16 One run was charged to Assenmacher, but it was unearned, as was the run charged to Hill. Atlanta won the game, 5-2, to take a three-games-to-one lead, and ultimately won the Series in six games. The Indians would have to wait another season to see if they could break the World Series drought.

Assenmacher re-signed with the Indians after the 1995 World Series. The Indians gave the lefty a two-year, $1.7 million contract.17 He was effective in 1996 with a 3.09 ERA and he held the opposition to a .260 batting average.

The Indians finished 1996 with the best record in baseball (99-62) and faced the Baltimore Orioles in the American League Division Series. The Indians managed only one win against the Orioles, but Assenmacher picked up that Game Three victory. It was his first postseason decision.

He improved on his 1996 stats in 1997, holding batters to a .231 batting average and .289 on-base percentage. The Indians won the American League Central with only 86 wins and faced the wild-card Yankees. The Orioles had the best record in the American League, but at the time, the rule was that the wild-card team would face the best team, unless that team was in the same division. So the 96-win Yankees opened the series at home, and moved to Cleveland for the last three games. In four appearances, Assenmacher pitched 3⅓ innings and gave up two earned runs, but he played an important role in the Indians’ Game Four and Game Five victories.

In Game Four, the Indians were down 2-1 going into the eighth inning. Their bullpen would have to hold the Yankees scoreless and hope that the offense would pick it up. That is exactly what happened. Assenmacher entered in the eighth and gave up a single to Paul O’Neill, but retired Bernie Williams and Tino Martinez on strikes before giving way to closer Michael Jackson. Jackson shut down the Yankees, and the Indians scored twice to win the game, 3-2. In Game Five, the Indians had a one-run lead when Assenmacher entered in the seventh. He forced O’Neill to ground into a fielder’s choice, and then Bernie Williams into a double play. He faced Tino Martinez in the top of the eighth and got Martinez to pop out to the catcher. José Mesa closed out the game; the Indians won the series and faced the American League’s best team, the Baltimore Orioles.

Assenmacher pitched in five of the six ALCS games and earned the win in Game Two. His stats took a hit in Game Five when he gave up two runs without recording an out, but he contributed to the Game Six win when he induced a groundout from B.J. Surhoff in the bottom of the eighth. The Indians won on a Tony Fernandez home run in the top of the 11th inning, propelling them into their second World Series in three years.

Assenmacher pitched four innings without giving up a run, but the Indians lost in the bottom of the 11th in Game Seven on Edgar Renteria’s single that scored Craig Counsell. The Indians’ World Series drought continued.

Lefties had more success than righties against Assenmacher in 1998. They batted .313 with a .361 on-base percentage. Conversely, right-handed batters hit .256 with a .340 on-base percentage. The Indians made the playoffs and faced the Red Sox in the American League Division Series, winning three games to one. Assenmacher appeared in three games for a total of one inning. He gave up two hits and no earned runs. The Indians played the eventual World Series champion New York Yankees in the American League Championship Series. The Indians lost, winning only two games, but Assenmacher again was steady in his role. As in the series against Boston, he did not give up a run; this time he pitched two innings.

Assenmacher appeared in 55 games for the Indians in 1999, posting a 2-1 record. But statistically speaking, it was the worst year in his career. His 8.18 ERA and 13.6 hits per 9 innings pitched were easily the worst of his career. The Indians again faced the Red Sox in the American League Division Series but lost 3 games to 2. Assenmacher pitched in just one game for a full inning, giving up five hits and three earned runs.

Assenmacher was granted free agency in November, 1999. In February 2000, Assenmacher signed a minor-league contract with the team that gave him his first shot, the Atlanta Braves.18 He was cut at the end of spring training, having given up eight earned runs in eight innings. “My arm’s just not coming around. It’s for the best,” he said. “Time to get on with my life. I’m 39 years old, played 14 years. It just wasn’t going to happen. Nothing to be ashamed of. … I did everything I could to keep my career going.”19

Assenmacher retired after the season. He later said “it really wore on me as a player not to see my kids enough. I just wanted to spend my retirement being at home and watching them grow up.”20

The Cubs asked Assenmacher to come back and sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” in September of 2004. When he was asked if he ever thought he’d get to sing at Wrigley when he was playing with the Cubs, he replied “not really. I never thought they’d get that desperate.”21

Assenmacher spent 10 seasons as the pitching coach at St. Pius X High School, outside of Atlanta, where he lived as of 2018 with his wife, Maggie. Together, they have five children: Jason, Candace, Lindsay, Morgan, and Clayton.

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted the following:

Aquinas College Athletics website (aqsaints.com/d/2016-aqbaseballrecords-1.pdf).

St Pius X Athletics website (spx.org/BaseballCoaches).

Notes

1 Murray Chass, “Left-Handed Relievers Find Long Job Security,” New York Times, February 21, 1999: SP2

2 “Baseball,” The Sun (Baltimore), November 21, 1985: 5C.

3 Richard Justice, “Expansion Issue Alive,” Washington Post, December 9, 1986.

4 Tim Kurkjian, “Don’t Expect Happy Ending for Yankees from Episode 5 of Martin-Steinbrenner,” The Sun, October 25, 1987: 4B.

5 Rich Lorenz, “National League,” Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1989: 4-5.

6 “Strawberry Bolts from Mets’ Camp,” The Sun, March 3, 1989: 4B.

7 Murray Chass, “Secret to Success: Retire Will Clark,” New York Times, October 6, 1989: D20.

8 Murray Chass, “Joyner Signs One-Year Pact With Royals for $4.2 Million,” New York Times, December 10, 1991: B21.

9 Ibid.

10 Andrew Bagnato, “Deal Off, Cubs Turn to Plan B,” Chicago Tribune, December 10, 1991: 4-2.

11 Joey Reaves, “Cubs, Sox Keep Most of Their Biggest Names,” Chicago Tribune, November 18, 1992: 4-7.

12 Jack Curry,“Yankees Trade Assenmacher (Will Hitchcock Be Moving In?),” New York Times, March 22, 1994: B12.

13 “Around Baseball,” Washington Post, April 11, 1995.

14 Murray Chass,“Indians Make a Strong Pitch, Too,” New York Times, October 16, 1995: C7.

15 Paul Hoynes,“Why Didn’t the 1995 Cleveland Indians Have Home-Field Advantage in the Playoffs?” Cleveland.com, October 29, 2015. (cleveland.com/tribe/index.ssf/2015/10/heres_why_1995_cleveland_india.html accessed 6/15/2016).

16 Patrick Reusse,“Cleveland’s Fortunes Take a Left Turn,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 26, 1995: C1, C4.

17 “Transactions,” Washington Post, November 3, 1995.

18 Murray Chass,“Baseball,” New York Times, February 6, 2000: SP2.

19 Jack Wilkinson,“Braves Notebook: End of March Ends Assenmacher March,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, April 1, 2000.

20 “’95 Cleveland Indians – Where Are They Now?” Cleveland Magazine, April 2005.

21 Scott Derenger,“The Suite Life: Paul Assenmacher,” Chicago Tribune, September 3, 2004.

Full Name

Paul Andre Assenmacher

Born

December 10, 1960 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.