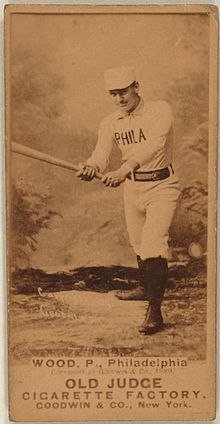

Pete Wood

“Former Well-Known Hamilton Ball Player Died in Chicago” headed the modest notice in the Hamilton (Ontario) Spectator on March 19, 1923. 1 The obituary briefly refers to careers in both baseball and medicine. What is not mentioned: Peter Burke Wood was a talented, intelligent, loyal, strong-willed, and troubled individual who, despite an intermittently brief major league career (1885; 1889), was nevertheless involved in a singular event in major-league baseball. That was the only battery formed by Canadian brothers, along with Fred Wood.

“Former Well-Known Hamilton Ball Player Died in Chicago” headed the modest notice in the Hamilton (Ontario) Spectator on March 19, 1923. 1 The obituary briefly refers to careers in both baseball and medicine. What is not mentioned: Peter Burke Wood was a talented, intelligent, loyal, strong-willed, and troubled individual who, despite an intermittently brief major league career (1885; 1889), was nevertheless involved in a singular event in major-league baseball. That was the only battery formed by Canadian brothers, along with Fred Wood.

Peter Wood was born on February 1, 1867 in Dundas, Ontario. He was the youngest son of John Frederick Wood, a prominent Hamilton financier, whose father was “an Irish-American farmer who had immigrated to the Niagara District shortly after the War of 1812.”2 John married Marietta Vinton, the daughter of a carpenter from Monroe County, New York, who brought his family to the Hamilton area in the 1850s. As Peter entered adolescence, Marietta began to suffer bouts of delusion and paranoia, requiring her to be admitted several times to the Toronto and Hamilton Insane Asylums. This left John as the primary caregiver for the four children. In addition to Peter was eldest sister Adelaide May (Addie), and brothers Jefferson Newell and Frederick Llewellyn Wood.

John had been a catcher at one time. As an 1884 report noted, he “still goes upon the diamond with his sons.”3 This early tutelage evidently made an impression on all three boys, as they would all end up playing ball professionally.

Organized baseball began in Hamilton in the 1850s, and from there, grew in popularity with teams like the Maple Leafs, Stars, and Clippers. These teams were supported by junior teams such as the Baysides, Primroses, and Hop Bitters, and it is likely that Peter played on some of these junior teams in the early 1880s. It is not until July 21, 1883 that we find ‘P. Wood’ listed as first baseman of the Hop Bitters, joining brother Fred, who was already their regular catcher. On August 20, Peter’s other brother Jeff made his way into the Hops lineup, marking the first time, though not the last, that all three Wood boys played on the same team.

As for Peter, he and Fred had been getting favorable reviews in the local press for their pitching and catching. However, the first recorded instance of Peter pitching is found on August 25, 1883. The Hamilton Spectator noted that “Reardon of the Hops left pitcher’s base and Pete Woods [sic] was put on instead.”4 Peter and Fred were also in demand outside of Hamilton: “The Wood brothers start on a tour this week, playing with local clubs at Barrie, Aylmer and Beamsville.”5 Even the Sporting Life took notice, calling them the “finest battery in Canada. … They are good batters, too.”6

Peter was further given high praise for his academic pursuits: “Peter B., the youngest brother of the Wood brothers, of noted baseball fame, … passed, at the closing in July last, a highly creditable examination. Peter, during his holidays, has distinguished himself as an A 1 all around baseball player, and undoubtedly he will have equal success in his educational pursuits.”7

In 1884, Peter played for the Hamilton Clippers of the Western Ontario League along with both his brothers. His debut was less than stellar; despite securing the victory, “P. Woods[sic], the pitcher for the Clippers, did not pitch very well, every one of the Baysides batting him easily.”8 All three brothers were in the Clippers lineup together for the first time on June 21, but Peter’s difficulties continued in pre-season play: “The display of pitching made by P. Wood was about the worst ever seen in the city.”9

Peter’s fortunes turned once the regular schedule commenced. In only the second league game on July 1, he allowed no hits over seven innings while striking out 13 London Alerts. Mysteriously, after the seventh inning, “the men were changed about.”10 Peter was moved to right field, where he saw the team’s bid for a no-hitter end in the ninth inning when the Alerts made two hits off relief pitcher Wilson.

Peter continued to pitch victoriously for the Clippers. He pitched another gem on August 2, allowing only one hit and no earned runs while striking out 11 in a 6-2 victory against the Hamilton Baysides. The 1884 Clippers went an undefeated 14-0 in league games, with Peter the winning pitcher for 12 of those.

Soon after the close of the season, Peter was called upon twice within eight days to act as groomsman to his brothers. Fred got married on October 28; Jeff followed on November 5.

The year 1885 was a seminal year in Canadian baseball history with the formation of the Canadian League, a professional circuit formed under the direction and financial backing of Guelph businessman and brewer George Sleeman. Teams from Guelph, London, and Toronto joined the Hamilton Primroses and Clippers in the league, and the Wood brothers again formed the core of the latter.

Soon into the season, however, Peter and his brother Fred were suspended for 30 days without pay and fined $15 each by the Clippers for “insubordination and disregard of the rules of the club.”11 The cause of the disagreement was the desire of the manager to replace their other brother Jeff with another player at first base. The brothers objected to the suspension and claimed their release from the Clippers. George Sterling, manager of the Clippers, stated that he “did not wish to keep the Woods from playing ball, and would release them as soon as the matter was decided” by the Judiciary Committee.12

Sterling kept his word, and the brothers were released on June 27. Despite courting offers from Guelph management, they were engaged a few days later by the other Hamilton team, the Primroses. Peter would pitch in only two games for the Prims, losing both.

Meanwhile, in the National League, the Buffalo Bisons were having troubles of their own. To avoid disbanding, they sold their star pitcher, James “Pud” Galvin. Manager Jack Chapman was dispatched to Canada on a hunt for players, as he had done the prior year while managing the Detroit Wolverines. That trip had netted Fred Wood for Detroit, and it’s reasonable to think that Chapman was aware of Peter.

After failing to secure Toronto pitcher William “Cannon Ball” Stemmeyer, Chapman set his sights on the newly acquired Primrose pitcher. Sporting Life pronounced Peter Wood “the most promising of all the pitchers in the Province of Ontario”13. Peter was in receipt of other offers from several other National League clubs. Also, his father was reluctant to let his young son — still just 18 — leave home. Nonetheless, Chapman was able to sign Wood for one month as change pitcher. His signing gave Buffalo the youngest pitching rotation in the league, along with second-year pitcher Billy Serad, age 23, and another 18-year-old rookie, Pete Conway. However, this would not turn things around for the Bisons.

Peter’s major-league debut occurred on July 15, 1885 against the league-leading Chicago White Stockings. Though he took the loss, his pitching line was more than creditable: he allowed only seven hits and two earned runs over nine innings. As an 18-year-old in his first major league game, he showed promise, and “created a furore in ball circles in Buffalo.”14 The Buffalo Tiger said of his debut: “The grand stand held its breath when Wood, the young Canadian pitcher, stepped into the box yesterday afternoon. … His pitching in the next inning was equally good, and when, later in the game, he put out on strikes the heavy hitters of the Chicago nine even after five balls had been called on him the crowd was wild with excitement. Wood struck out seven men of the Chicago nine.”15

A day later, in the back end of a doubleheader, Peter had a rough outing. He lasted only three innings before falling ill. However, he soon returned to face Providence on July 20. In what would prove to be his finest major-league pitching performance, he scattered only four hits and one earned run over nine innings to earn his first major-league win. He also managed two hits off one of the top pitchers in all of baseball at the time, Old Hoss Radbourn. The Hamilton Spectator predicted, “it looks much as if the young Canadian pitcher was going to create a revolution in the fortune of the club.”16

Wood’s 1885 campaign proved streaky, however; after his dominance vs. Providence, he lost his next six decisions, only to follow those up with four straight wins. He finished the season with a lowly 8-15 record, though commensurate with Buffalo’s record of 38-74. But a 4.44 ERA and a .221 batting average, though unspectacular, were not without some merit for an 18-year-old rookie.

The Bisons ventured north to Hamilton on September 28 to play an exhibition game against the Canadian League champion Clippers. They were easily defeated, 7-2 — but, likely catering to the Hamilton crowd, Chapman had inserted Peter’s brother Fred into the lineup to catch him. The Bisons were battling for last place with Detroit and St. Louis, so they had little to lose by keeping both Woods in the lineup for the next league game. Peter and Fred made history on September 30, 1885 as the only Canadian brothers ever to form a major-league battery. Buffalo fell 5-3 to Boston.

Though Peter remained with the team until the end of the season, it was the last game that year for either. As for the Bisons, their dismal standing caused them to leave the National League and head to the minor International League for 1886.

Despite rumors that he had been signed by Troy in March 1886, Wood telegraphed Manager Chapman on April 15 to accept his terms and return to Buffalo. He reported a month later when his academic term at University of Toronto ended. Meanwhile, he kept in shape by playing with the university’s varsity team.

Wood appeared in 19 games with Buffalo, ending up with another losing record of 6-11 despite a healthy 2.18 ERA, coupled with a strong .318 batting average. However, a report in the Buffalo Courier shed light on some issues between him and his teammates: “There is a clique in the nine doing all they can against the Wood brothers, and trying to induce others not to give them support in games.”17 The rift grew after a game versus Utica on June 18, where he was alleged to have “deliberately pitched the ball where the Utica batsmen could hit it easiest.”18

The press claimed that Wood was playing for his release, and a few weeks later, on July 14, he was suspended for the rest of the season on the grounds of indifferent play. A few days later Wood offered the Buffalo directors $300 if they would “reconsider their sentence of suspension and simply release him.”19 With the papers calling him a “rather useless ornament to the Buffalos,” he was granted his release. 20

He returned home after signing with the rival Hamilton Clippers, to the delight of the team and community. After a successful outing against the same Utica team, “the title deeds of the city of Hamilton were handed over to Pete Wood.”21 Wood did not disappoint; he finished the season with a 14-7 record (meaning a total of 20 wins between the two clubs) and 1.66 ERA. He also continued his consistently strong work at the plate with a .317 average.

Before the start of the 1887 campaign, it was reported that Wood was sold to the New York Giants, but he remained with Hamilton (now known as the Hams). As the ace, he finished the season with 21 wins and an impressive .371 batting average. He could not avoid trouble, however: on July 16, he was suspended and fined $150 for indifferent play and general insubordination. Wood responded in a letter to the editor of the Hamilton Spectator, noting that the team had won six of the last eight games in which he had pitched. He was reinstated the following week, and he appeared to make amends with Hamilton management. Despite an offer of $1,000 by the New York Metropolitans of the American Association for his release, the Clippers “decided that he was too valuable a man to part with. He is a splendid pitcher and it is to be hoped that his suspension will not interfere with his work in the future.”22

The Hams were struggling, however; low attendance caused them to contemplate disbanding. On September 7, William Stroud stepped down as manager, replaced by second baseman Charles “Chub” Collins. On September 23, with the team floundering in fifth place, Collins was released and Wood was appointed in his place. He was successful in his only professional stint as manager, compiling a winning record of 3-2.

Wood’s stellar 1887 performance won renewed attention from major-league clubs for his services. Cleveland (with an offer of $3,000 plus $1,200 to Hamilton for his release), Chicago, New York and Baltimore all expressed interest. It was even reported that Wood had telegraphed Buffalo management to accept their terms, but he instead accepted a better offer to remain in Hamilton, with a unique contract: “Under no circumstances can he be fined or suspended, nor is he to play unless he feels like it. Then ‘Pete’ gets $2,700.”23

Wood emerged as a star in the International Association in 1888, compiling 37 wins with the Hams. “He has splendid control of the ball and can put it over the plate whenever he wants to. Wood has deceptive curves, and one great feature about him is that he never gets rattled. [He] is also a strong right-handed batter. He never waits to get his base on balls, but lets fly at the first ball that comes near him.”24 He was referred to on more than one occasion as “Invincible Wood,” and the Syracuse Standard declared he “is about as good a ball player as the world contains.”25 That came after he shut out the league-leading Stars 2-0 on only three hits on September 10.

His achievements did not go unnoticed; the New York Clipper reported that “Pete Wood … who is considered the best pitcher of the International Association, is wanted by several of the clubs of the larger organization.”26 The Chicagos wanted him “very badly, and are willing to pay a good sum for his release.”27 The St. Louis Browns telegraphed, asking how much the Hams would take for his release. “The modest sum of $8,000 was the figure asked.”28 Yet despite the offers, Wood preferred to close out the season in Hamilton.

Interest in his services intensified after the season ended. Philadelphia emerged victorious by sending $3,000 to Hamilton for his release (half of which Wood would get) and giving Wood an additional $3,000 a year, including $1,000 advance money29.

Wood’s debut with the Quakers on May 31, 1889 vs. Indianapolis was impressive. He allowed only two earned runs while striking out six in six innings in an 11-4 victory over the Hoosiers. But he would not pitch again for nearly a month, either because of arm troubles or simply because Manager Harry Wright had better options in Charlie Buffinton and Ben Sanders. Wright did like Wood for his “sobriety, gentility and good moral conduct.”30 Yet according to another report that same day, he was “apparently convinced that Pete isn’t fast enough for the League.”31

Wood appeared in only two more games with Philadelphia. His last major-league appearance was in relief of Sanders in a losing effort vs. Cleveland on July 17, 1889; the Spiders made eight hits off him over four innings. On July 20, Wood was given his release. Wright was quoted as saying that “he has fallen short of expectations to a very great extent.”32 The official reason given, though, was simply that “the club has too many pitchers.”33

The NL’s Indianapolis Hoosiers would soon claim Wood’s services, but he instead accepted an offer of $1,000 from the London (Ontario) Tecumsehs of the International Association to pitch for the remainder of the season. This choice to play for his hometown team again resulted in the end of his major-league career, but perhaps it was for the better. In 12 starts with London, he went 7-3 and “proved to be the same old Pete.”34 Sporting Life declared that “the Phillies undoubtedly let a prize slip through their fingers.”35 By contrast, though, the London press talked of an ailment (“Pete Wood’s arm is a trifle off”).36

The offseason was a busy one for Wood. First, he married Gilbertha Rymal, the daughter of George Washington Rymal, a farmer, and Margaret Cummins, on October 23, 1889 in East Flamboro, Ontario. The marriage notice in the Hamilton Spectator exclaimed, “he is worthy of the high esteem in which he is held by his Hamilton friends, as few ball-players are as honest and straightforward as Pete. Mr. and Mrs. Wood will reside in London, where Pete expects to play next season.”37

He also took time to indulge in another pursuit: “Pete Wood does not allow matrimony or baseball to interfere with his musical inclinations. Pete is a prominent member of the London Young Liberal Minstrel Club, and will give a banjo act there on New Year’s Eve.”38

By then having settled in London, Peter enrolled in the Medical Department at Western University — primarily at the behest of his father, who was a “stern, strong-willed person who did not think much of a career in sports.”39 Peter continued his strong academic success, achieving honors on his first-year examinations in March 1890.

But baseball season was approaching, and in April 1890, Wood signed with the Toronto Canucks of the International Association. He was named captain and played first base primarily, pitching in only four games owing to shoulder issues. Further challenges were to come: an attack of typhoid fever and the folding of the International Association. These were offset by a joyous occasion. On August 9, 1890, he and Bertha welcomed Edmund Burke Wood, the first of four sons. Edmund was followed by Clifford in 1892, Frederick in 1894, and Reginald in 1897. Once fully recovered, he finished the season playing occasionally with an amateur team from his birthplace of Dundas, Ontario.

For the next few years, Peter mainly focused on his medical studies. He passed his final examinations in September 1893, obtaining his physician’s license a month later. Throughout, he continued to play ball sporadically with a variety of picked nines, including the Tilsonburg (now Tillsonburg, Ontario) Blues and the London Medical College team. He again played first base on occasion with Dundas, now of the Canadian Amateur Baseball Association, in 1893. Two years later, Wood’s arm had regained enough strength for him to return to pitching and help lead the 1895 Guelph team to the championship of the Western (Canada) League. He received special medical training in New York City in 1896, and closed out his professional baseball career that same year with the London Alerts of the Canadian League, leading the team with a .339 batting average.

In August 1897, Wood pitched a game with an amateur St. Thomas, Ontario team, holding his opponents to four hits. A month after that, he headed down to Anaconda, Montana; after six weeks, he was so “favorably impressed that he [made] Anaconda his home.”40 In April 1898, he successfully passed the examination of the Montana State Board of Medical Examiners. He continued to play pickup ball every now and then with teams of local businessmen and professionals. In October 1899, however, he landed in trouble when he was arrested and charged with practicing medicine without a certificate — he had neglected to have his license recorded. He was fined $10. By then he had moved 20 miles to Butte, Montana, where he worked with the Western Medical Dispensary. There he had success treating nervous diseases.

By 1902, Wood had returned to Hamilton, Ontario, and continued to practice medicine. That on March 2, his father died at the age of 65 after a lengthy battle with Bright’s (kidney) Disease.

Wood explored other areas of interest over the next several years. By 1905, he had delved into horse racing; two of his horses would become famous harness-racing pacers. He also pursued an interest in local affairs, running as alderman for Hamilton. Though heralded as a potential “first rate alderman,” he was not elected.41 Throughout, he still managed to get in a game or two. “Pete Wood Isn’t Dead Yet” declared the London Free Press, which mentioned that Wood, “of International League fame, [was] in the box for the visitors,” the St. Thomas Pastimes.42

By 1909, Wood had relocated his practice to Toronto, working for the Keeley Institute, which offered medical treatment to alcoholics. On December 21, 1913, his mother died in an Aged People’s House in London as a result of accidental head injuries. Around this time, it was becoming apparent that the sternness of his father, along with his mother’s mental health issues and his unhappiness at having to pursue medicine, had taken their toll on him. In June 1914, he found himself in Police Court on a charge of drunkenness, “having already been fined more than a dozen times for the same offence. His sons have always pleaded that their father be sent to the Industrial Farm, but by skillful pleading the Doctor has hitherto avoided the sentence. Yesterday, however, the patience of Magistrate Ellis came to an end, and the Doctor was sent to the farm for an indeterminate period of two years.”43

Little is known of Wood’s last years. By 1917, he had relocated to Chicago, though he is nowhere to be found in the 1920 census, while his four sons are found in Chicago with their mother, who is mysteriously listed as widowed.44 But what we do know is that on March 15, 1923, at the age of only 56, Peter Burke Wood succumbed from splenic anemia and — according to his death certificate — non-alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver. He is buried in Mount Greenwood Cemetery, Chicago. There he was later reunited with his wife (died 1948) and eldest son (died 1941). His life, much like his career in the major leagues, ended far too soon.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

Ball, David and David Nemec. Major League Baseball Profiles: 1871-1900, Volume 1 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011).

Shearon, Jim. Over the Fence is Out! (Kanata, Ontario: Malin Head Press, 2009).

The author consulted many newspapers, including: Buffalo Commercial, Buffalo Courier, Buffalo Morning Express, Buffalo Evening News, Butte Daily Post, Butte Miner. Chicago Eagle, Chicago Tribune. Detroit Free Press, Glens Falls Times, Lincoln Evening Call, London Advertiser, Montana Standard, Philadelphia Inquirer, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, Syracuse Standard, Toronto News, Toronto World, Troy Palladium, and Washington Evening Star

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Partridge, Tyler. “The History of Canadian Baseball Brothers,” CANUCKBASEBALLPLUS, https://canuckbaseballplus.com/2018/12/11/the-history-of-canadian-baseball-brothers/, accessed November 15, 2019.

Archives of Ontario. Series RG 10-268. Queen Street Mental Health Centre Histories

Archives of Ontario. Series RG 10-271. Health Queen Street Muster Roll Female

Archives of Ontario. Series RG 10-272. Queen Street Mental Health Centre Records

Archives of Ontario. Series RG 20-164-0-2. Toronto Municipal Farm for Men, Langstaff (Thornhill) Institutional Register, 1917-1928.

The author also consulted the Baseball Hall of Fame Library file, along with a variety of genealogical resources, including US & Canadian Census records, Assessment Rolls, Voters Lists, Land Records, City Directories and Medical Registers.

Notes

1 “Dr. Peter Wood,” Hamilton Spectator, March 19, 1923.

2 Daniel J. Livermore. “Edmund Burke Wood,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_edmund_burke_11E.html, accessed July 24, 2019.

3 “Baseball,” Detroit Free Press, March 21, 1884: 7.

4 “Baseball Match at Dundurn — The Hops Victorious,” Hamilton Spectator, August 27, 1883.

5 “Baseball,” Hamilton Spectator, August 22, 1883.

6 “Our Canada Letter,” The Sporting Life, September 24, 1883: 6.

7 “Baseball,” Hamilton Spectator, September 4, 1883.

8 “The World of Sport,” Hamilton Spectator, May 19, 1884.

9 “Baysides and Clippers,” Hamilton Spectator, June 23, 1884.

10 “The World of Sport,” Hamilton Spectator, July 2, 1884.

11 “Notes,” Hamilton Spectator, June 22, 1885.

12 “The Canadian League Meeting,” Hamilton Times, June 27, 1885: 1.

13 “The Bisons,” The Sporting Life, July 22, 1885: 1.

14 “Pete Wood Surprises Them,” Toronto Mail, July 18, 1885: 9.

15 “Pete Wood Surprises Them,” Toronto Mail, July 18, 1885: 9.

16 “Pete Wood’s Success,” Hamilton Spectator, July 21, 1885.

17 “Notes,” Hamilton Spectator, June 25, 1886.

18 “Wood’s Wily Work,” Buffalo Times, June 19, 1886: 5.

19 Buffalo Times, July 20, 1886: 5.

20 Buffalo Courier, reprinted in the Hamilton Spectator, July 14, 1886.

21 “Notes,” Hamilton Spectator, August 2, 1886.

22 “Pete Wood Reinstated,” Hamilton Spectator, July 27, 1887.

23 Buffalo Commercial, May 17, 1888: 3.

24 “The Hamilton Team,” Hamilton Spectator, March 29, 1888.

25 “Wood’s Great Pitching,” Hamilton Spectator, September 12, 1888.

26 “Stray Sparks From the Diamond,” New York Clipper, October 20, 1888: 10.

27 “Notes,” Hamilton Spectator, August 22, 1888.

28 “Notes,” Hamilton Spectator, August 15, 1888.

29 “Baseball,” Hamilton Spectator, October 23, 1888.

30 “Philadelphia Pointers,” The Sporting Life, July 10, 1889: 4.

31 “Philadelphia Pointers,” The Sporting Life, July 10, 1889: 4.

32 Pittsburgh Dispatch, reprinted in the Hamilton Spectator, July 4, 1889.

33 “Stray Sparks From the Diamond,” New York Clipper, July 27, 1889: 9.

34 “London Lines,” The Sporting Life, August 21, 1889: 1.

35 “London Lines,” The Sporting Life, August 21, 1889: 1.

36 London Free Press, August 27, 1889: 3.

37 “Pete Wood Married,” Hamilton Spectator, October 24, 1889.

38 Buffalo Courier, December 20, 1889: 3.

39 Kenneth Alan Wood (grandson), email correspondence with author, November 10, 2018.

40 “Come To Stay,” Anaconda Standard, November 6, 1897: 3.

41 Hamilton Times, December 30, 1905.

42 “Pete Wood Isn’t Dead Yet,” London Free Press, May 25, 1905.

43 “Abolition of Bar an Act of Charity,” Toronto Globe, June 20, 1914.

44 “United States Census, 1920.” Database with images. FamilySearch. http://FamilySearch.org : 14 June 2020. Citing NARA microfilm publication T625. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.

Full Name

Peter Burke Wood

Born

February 1, 1867 at Dundas, ON (CAN)

Died

March 15, 1923 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.