Roger Connor

Underappreciated in his late-19th-century heyday and largely forgotten for decades thereafter, Roger Connor was baseball’s first great slugger, the game’s career home-run leader prior to the arrival of Babe Ruth. A fastball-loving left-handed batter, Connor spent virtually every season between 1880 and 1894 among league leaders in a wide array of offensive categories. Over time he also developed into an adept fielding first baseman and a skillful baserunner, perhaps surprising attributes given his size – 6-feet-3 and 220 pounds. Towering over his contemporaries, Connor was also the chief inspiration for the moniker bestowed on New York’s first great baseball team: the Giants. But all this did little to generate enduring interest in him. A quiet, dignified man both on and off the diamond, Connor was rarely involved in the kind of incident that spawned press attention or gave rise to the memorable anecdote. Although respected and well-liked, Connor was by and large taken for granted by baseball fans and the sports media of his day, generally viewed as an accomplished but colorless professional. Once his playing career was over, the memory of Roger Connor did not linger in the game’s consciousness. Nor was Connor recognized when the Hall of Fame began to open its doors to the greats of his era.

Underappreciated in his late-19th-century heyday and largely forgotten for decades thereafter, Roger Connor was baseball’s first great slugger, the game’s career home-run leader prior to the arrival of Babe Ruth. A fastball-loving left-handed batter, Connor spent virtually every season between 1880 and 1894 among league leaders in a wide array of offensive categories. Over time he also developed into an adept fielding first baseman and a skillful baserunner, perhaps surprising attributes given his size – 6-feet-3 and 220 pounds. Towering over his contemporaries, Connor was also the chief inspiration for the moniker bestowed on New York’s first great baseball team: the Giants. But all this did little to generate enduring interest in him. A quiet, dignified man both on and off the diamond, Connor was rarely involved in the kind of incident that spawned press attention or gave rise to the memorable anecdote. Although respected and well-liked, Connor was by and large taken for granted by baseball fans and the sports media of his day, generally viewed as an accomplished but colorless professional. Once his playing career was over, the memory of Roger Connor did not linger in the game’s consciousness. Nor was Connor recognized when the Hall of Fame began to open its doors to the greats of his era.

More than 40 years after Connor’s death, rectification of this slight commenced with the historic achievement of another quiet, dignified professional, Hank Aaron. Among the questions provoked that April 1974 evening when Aaron smashed his 715th home run was this one: If Aaron had just broken Babe Ruth’s career home-run record, whose record had Ruth broken? The answer to that question shined the spotlight on long-neglected Roger Connor. Two years later Connor received his due when ceremonies in Cooperstown included the belated but eminently deserved induction of Connor into the ranks of baseball’s immortals.

Roger Connor was born in Waterbury, Connecticut, on July 1, 1857, the third of 11 children born to Murtagh Connor and his wife, the former Catharine Sullivan.[1] Roger’s parents were Irish Catholic immigrants from County Kerry who married some six weeks after his father’s arrival in America in September 1852.[2] Like many in Waterbury, Murtagh Connor found work in the city’s brass factories. And like many an immigrant struggling to provide for an ever-increasing family, he did not approve of his oldest son’s enthusiasm for baseball. Years later, Roger would recall the parental strappings that playing ball instead of earning a day’s pay had brought him in his youth.[3] But punishment failed to deter him from playing ball whenever he could. In 1871, Roger – now 14 years old and already 6-feet and 180 pounds – set off for New York, where he worked odd jobs while trying to catch on with junior baseball teams as a left-handed third baseman.[4] Three years later he returned home to find the family in crisis. Murtagh Connor had died unexpectedly in September 1874, leaving Catharine to manage the children, whose number was subsequently increased by the birth of baby Joseph some two months after his father’s death. Now 17 years old, Roger joined his older sisters in the Waterbury work force. He also began serving as surrogate father for the younger Connor children, particularly Joe.

Family travails, however, did not loosen baseball’s grip on Roger Connor. In 1877 he joined the Waterbury Monitors, a local semipro nine. The statistical record for Connor’s play with the Monitors is mostly lost but events demonstrate that he made an impression sufficient to gain a tryout invitation from the New Bedford Whalers of the International Association, a top-flight minor-league team. During his two-week audition, Roger, then a right-handed batter, proved unable to handle International Association-level pitching. After his release[5], Connor returned to the Monitors, where a move to the left side of the batter’s box produced dramatic improvement. By midseason he was back in the International Association, playing third base for Holyoke. The following season, he was appointed field captain of the Holyoke team, a position the reserved Connor did not find congenial. He resigned the post in August.[6] But discomfort in a leadership role had had little negative effect on Connor’s playing performance. In 45 games, he amassed 77 base hits, batting a sparkling .367 for the 1879 season.[7] Perhaps more important to his future, Connor had caught the eye of Bob Ferguson, the crusty pioneer era and National Association star then serving as player-manager for rival Springfield. Summoned late in the 1879 season to take charge of the National League’s Troy Trojans, Ferguson would remember the young slugger from Holyoke when he began formulating plans to revamp his new team.

The year 1880 was a momentous one for Connor. On the professional front, Troy manager Ferguson began to stockpile his roster with promising talent, beginning with Connor. Before the season was out, four other future Hall of Famers – Dan Brouthers, Buck Ewing, Tim Keefe, and Mickey Welch – would don a Troy uniform. And it was the acquisition of that uniform that precipitated the signal event of Roger Connor’s personal life: encounter with Angeline Mayer.[8] Dispatched to a Troy shirt factory for individualized tailoring (as none of the available Trojan uniforms fit the outsized Connor), he was smitten during conversation with a comely blond seamstress who knew her baseball. But he was apparently too bashful to take matters further. Sometime thereafter, Connor found the courage to await the arrival of the seamstress at the factory entrance, hopeful that she would remember him. That hope was more than realized. Upon spotting him, Angeline smiled and exclaimed, “Hello, Roger Connor,” extending her hand to greet him. With that meeting, Connor had secured his life partner.[9] He and Angeline wed in September 1881 and lived happily together for the next 47 years.[10]

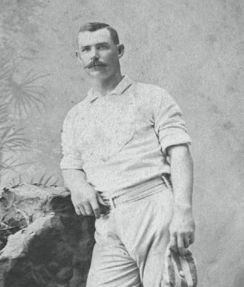

The good fortune that Connor experienced in his personal life was replicated on the diamond. He had a banner rookie season for the fourth-place (41-42) Trojans, playing in all 83 Troy games and hitting .332, third best in the National League. He also ranked among league leaders in slugging percentage (.459), OPS (.816), on-base percentage (.357), RBIs (47), hits (113), and total bases (156). His fielding, however, was another matter. Playing a barehanded third base, the big lefty made 60 errors and posted an .821 fielding percentage, dismal even by 1880 standards. Even so, the season had been a great personal success. The arrival of this new force on the baseball scene was heralded in the customary manner: the publication of a profile in the New York Clipper. Under the inked likeness of a handsome young man with striking dark mustache, the Clipper extolled Connor’s hitting, allowing that at present “he shines more as a batter than as a fielder.”[11] A switch to first base for the 1881 season occasioned some improvement in Connor’s fielding but his hitting tailed off. He batted only .292 with reduced numbers in virtually every other offensive category. The team also faltered, falling to 39-45, fifth place in the standings. Still, the campaign was not without highlights, the foremost being an 8-7 victory on September 10 over Worcester, courtesy of a ninth-inning grand slam by Connor, the first bases-loaded homer in National League history.[12]

The 1882 season saw resurgence in Connor’s bat and the end of Troy’s tenure as a major-league venue. Notwithstanding a midseason shoulder injury (which, serendipitously, necessitated his semi-permanent stationing at first base), Connor was again among National League leaders in multiple offensive categories: first in triples (18) and among the top five in slugging (.530), total bases (185), batting average (.330), OPS (.884), and on-base percentage (.354). But the other budding stars on the Troy roster – Buck Ewing (.271), Mickey Welch (14-16), and, particularly, a half-trying Tim Keefe (17-26) – did not keep pace.[13] A lackluster seventh-place (35-48) record marked the end of the line for Troy. And the beginning of Roger Connor’s glory days. He would soon be heading for New York.

The close of the 1882 campaign found baseball in a peculiar place. That season, the established National League had been challenged by a rival, the six-team American Association. Yet neither circuit had a team in either of the country’s two premier sporting markets, New York and Philadelphia. Both metropolises had been without a big-league team since their expulsion from the National League after the 1876 season.[14] Since then, baseball fans in Gotham had had to content themselves with the play of independent teams, the best of which was an outfit called the Metropolitan of New York. The Mets were organized in August 1880 by a marginally talented Massachusetts shortstop named Jim Mutrie and bankrolled by John B. Day, a prosperous tobacco merchant originally from Connecticut. During the 1882 season the team demonstrated its mettle by playing National League and American Association opponents tough. With its small-market teams in Troy and Worcester slated for liquidation, a duly impressed National League invited the Mets to join the circuit for the 1883 season. At first, it appeared that Mets boss Day had declined the invite, placing the Mets in the American Association instead. But Day actually had bigger plans, namely, running a New York team in both major leagues. And the nucleus of his National League team would be refugees from the Troy Trojans, starting with Roger Connor.[15]

The first prominent signee of the fledgling New York Gothams, Connor did not disappoint his new employers. In 1883 he had his finest season to date, once again ranking second in the league in batting average (.357), and in the top three in hits (146), on-base percentage (.394), slugging (.506), total bases (207), and triples (15). And this time he had ample support from fellow Troy alums Ewing (.303 with a league-leading 10 homers) and Welch (25 wins). But the Gothams as a whole were mediocre, their sixth-place (46-50) finish disappointing in its own right and inferior to that of the Mets, the disfavored stepchild of team owner Day. Behind the stalwart hurling of 41-game-winner Tim Keefe – signed by management but deemed unworthy of a spot on the Gothams – the Mets had achieved a commendable 54-42 record and a first-division finish in an American Association now expanded to eight teams.[16]

The 1884 season was a mixed one for Connor and his team. On the individual level, Roger had a solid, if unspectacular, year, hitting .317 with 82 RBIs, a new personal best in a season extended to 116 games, all of which he played in. But defensive problems returned. Strangely, Connor was moved off first base to accommodate a Gothams rookie, the untested Alex McKinnon. Rotated around second (67 games), center field (37 games), and third (12 games), Connor fielded each of these positions poorly. Still, the Gothams improved, advancing a notch to fourth place. This modest upturn in team fortunes, however, did little to alleviate the dilemma at headquarters. Despite the inattention of ownership, the unloved Mets had won the 1884 American Association pennant. Drastic measures were required to reverse the pecking order of the New York nines and John B. Day took them. First, he reassigned Mets manager Jim Mutrie to the Gothams. Day then engaged in some rule-bending maneuvers to ink Mets stars Tim Keefe and Dude Esterbrook to Gothams contracts.[17] Future Hall of Famers Jim O’Rourke and John Montgomery Ward were also secured for the team. With six Cooperstown-bound players in a Gothams uniform for the 1885 season, the team played superb baseball, compiling an 85-27 record, the best ever recorded – for a team that finished in second place. Incredibly, the Chicago White Stockings, with Cap Anson, King Kelly and John Clarkson in the prime of their own illustrious careers, had been two games better. Meanwhile, the denuded and disheartened Mets staggered to a seventh-place finish in the American Association. Two years later, the franchise would be disbanded.

Connor had contributed to the Gothams’ 1885 success by having arguably the finest season of his 18-year major-league career. The 28-year-old slugger won the National League batting crown with a .371 average. Connor also led the league in hits (169), total bases (225), and on-base percentage (.435) while earning a top-five grade in triples (15), slugging (.495), OPS (.929), walks (51), and runs scored (102). Perhaps even more remarkable, the lusty swinging lefty had struck out only eight times in 506 plate appearances. Connor even began to exhibit signs of fielding prowess. Relocated to first base, he posted a respectable .975 fielding average, an augury of the fine defensive play that he would soon become respected for. Another under-recognized Connor talent was also coming to the fore: baserunning. Fleet afoot for so large a man, Roger unnerved opposing infielders with base path daring and a hard pop-up slide, a maneuver he was the first to popularize. And if all this were not enough, Connor served as the most visible manifestation of the moniker conferred upon the New York team during the 1885 season: Giants.[18]

A solid follow-up performance by Connor and his mates in 1886 was again insufficient to overcome the defending pennant winners, Chicago’s 90-34 record ending well clear of the third-place (75-44) Giants. The Connor ledger for the season was outstanding in all categories. He hit .355 and led the league in triples, a Connor specialty, with 20. He was also familiarly among league leaders in slugging (.540), OPS (.945), total bases (262), hits (172), and on-base percentage (.405). He also hit the first home run believed to have cleared the stadium confines at the original Polo Grounds, a mammoth late-season wallop off Providence ace Hoss Radbourn. The Connor highlight of the year 1886, however, occurred away from the field. That September, Angeline gave birth to a baby girl whom her parents named Lulu.[19]

In 1887 the National League lengthened the pitching distance to 55½ feet and instituted a short-lived scoring change. For this one year, a walk would be deemed a base hit for batting-average purposes. The 75 passes accumulated by the strike-zone-savvy Connor was not only the second most received by a National League player that season. It also inflated his official batting average to a career-high .383.[20] Connor was his usual potent self when swinging the bat, as well. He poled a personal best 17 home runs while finding his customary place among league leaders in triples, RBIs, slugging, on-base percentage, OPS, and total bases. Nor was his outstanding 1887 performance confined to the batter’s box. Connor stole 43 bases and topped the league’s first basemen in fielding percentage (.993), the first of four times he would snag that honor. But the performance of other Giants did not match his and the team continued its slide in the standings. New York’s 68-55 record was good for no better than fourth place. For Connor, the Giants’ tepid performance was dwarfed by family tragedy. Late in the 1887 season, daughter Lulu contracted dysentery when brought on a road trip. She died in September, just before her first birthday. To add to Connor’s anguish, the child had not been baptized, a grave parental failing for one as devout as Roger Connor. According to granddaughter Margaret Colwell, Connor always deemed Lulu’s death divine retribution for having been married outside church to a non-Catholic.[21]

In 1888 the star-laden Giants roster finally played to its potential, coasting to the pennant. Apart from a substandard .291 batting average, Connor placed in the league top five in almost every offensive category. And as in years past, Connor’s performance was largely taken for granted, with press coverage of the team focused on more colorful personalities like manager Jim Mutrie and stars Buck Ewing and John Montgomery Ward. The lack of attention had no visible effect on Connor. He was his same reliable self in the postseason, batting .303 as the Giants topped the American Association champion St. Louis Browns in the 1888 postseason series. The following season was played under gathering storm clouds, particularly in New York. At the season’s outset, the Giants had to contend with the loss of their ballpark, the original Polo Grounds having been razed to complete the uptown Manhattan traffic grid, the Tammany Hall connections of John B. Day notwithstanding. After unhappy stays in Jersey City and Staten Island, the team found a site for new grounds in far north Manhattan.[22] Once their New Polo Grounds was erected, the Giants caught fire, nipping the Boston Beaneaters at the wire for a second consecutive pennant. New York then successfully defended its “World Series” crown, defeating the American Association Brooklyn Bridegrooms in a championship match in which Connor batted .343 with 12 RBIs, a fitting coda to a season in which he had led the National League in that statistic with 130.

Team owner Day derived little pleasure from the Giants’ triumph, having been preoccupied all season with increasing troubles on the labor front. Long resentful of the reserve clause and then further antagonized by a tightfisted salary classification scheme adopted by National League magnates (over Day’s objection) prior to the 1889 season, the players had made discreet noise about rebellion while the schedule ran its course. And Day’s Giants, particularly visionary union leader John Montgomery Ward, were at the center of player unrest. Barely a week after New York’s 1889 postseason victory, the players made their move, Ward announcing the formation of a new major league, one that would be controlled by the players themselves. In the recruitment battles that ensued, Ward was ably assisted by Giants stars Tim Keefe and Jim O’Rourke. But the new Players League had no stauncher a supporter than the Giants taciturn first baseman, Roger Connor being one of the league’s first enlistees.

Having received a handsome $3,500 salary in 1889[23], Connor was hardly the victim of financial oppression. And like most of his Giant teammates, he was genuinely fond of Day, a generous and convivial man on a first-name basis with many of his players. But Connor held strong views on the rights of labor and the need for player union solidarity. Thus, none of Day’s blandishments – including pleas personally conveyed at the Connor residence in Waterbury – could induce Roger to renege on his commitment to the Players League.[24] The depth of Connor’s allegiance to the new circuit was later displayed when wavering by Buck Ewing and others was reported during the 1890 season. Such news prompted a passionate rebuke from the normally diffident Connor, who denounced hints of weakness or irresolution in the ranks.[25] Like most of his New York teammates, Connor had donned the uniform of the Ewing-led Players League Big Giants, playing first base in Brotherhood Park (later Polo Grounds IV), a newly constructed edifice separated by no more than a ten-foot alley and the stadium fences from the New Polo Grounds (later Manhattan Field), home of the depleted Real Giants of John B. Day.[26] Connor’s commitment to the Players League was backed by performance. He batted .349 with a league leading 14 home runs, ironically, the only time the 19th century’s long-ball king would ever lead a circuit in four-baggers. Connor was also the leader in slugging (.548) and OPS (.998) while in the top five in on-base percentage (.450), runs scored (133), and total bases (265). He was also the league’s top fielding first baseman (.985) and stole 22 bases.

With most of baseball’s star performers in a Players League uniform, the new enterprise outperformed the established National League and the weaker American Association on both the field and at the gate. But the Players League’s financial backers had not realized much profit on their investment and would prove no match for the hard-nosed A.G. Spalding in postseason settlement negotiations. Within weeks of the close of the 1890 season, the Players League had been talked into surrender, with its franchises either consolidated with National League counterparts or dissolved entirely. After only one season, the Players League was, in Spalding’s words, “dead as the proverbial door knob.”[27] While the demise of the league was dismaying to ardent supporters like Roger Connor, the year 1890 had not been without compensating events. With a view toward increasing their family, Roger and Angeline had visited a Catholic orphanage in New York that summer, hoping to find a blond child in Lulu’s image. While there, Roger spotted a dark-haired little girl sitting alone, quietly singing to her doll. A nun related that her name was Cecilia and that she had recently been left on the doorstep with a note reading, “Born June 21, 1888.” When Roger stooped over and called to her, the child ran directly to him and threw her arms around his neck. And would not let go. Shortly thereafter, Roger and Angeline left the premises with a new daughter who would bring them much joy.[28]

Like most of his Players League Giant teammates, Connor returned to the National League Giants for the 1891 season. But the situation was much changed from the recent championship years. Tension abounded on the field between the Players League returnees and the National League loyalists; in the dugout, where a disabled Buck Ewing effectively supplanted Jim Mutrie as Giants manager, and in the front office, where a near-bankrupt John B. Day was forced to cede operational control of the franchise to E.B. Talcott and his Players League partners. Before the 1891 season was out, longtime Connor teammate Tim Keefe had been released while Mickey Welch and Jim O’Rourke, a fellow Connecticut Irishman and close friend, were near the end of the line. At age 34, moreover, Roger himself was now past his prime. He batted only .290 for the 1891 season with power numbers that, while still decent, were not up to the Connor norm.

With further changes imminent in the Giants lineup, Connor made the break. In October 1891, he jumped to the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association. A month later, the Association folded with four of its franchises being absorbed into a new 12-team National League. Assignment to the Philadelphia Phillies seemed to rejuvenate Connor. Playing in all 155 league games during the 1892 season, he led the NL in doubles (37), was second in home runs (12), and in the top four in OPS (.883), walks (116), runs scored (123), total bases (261), slugging (.463), and on-base percentage (.420). He led National League first basemen in fielding percentage (.985) and stole 22 bases. With a Hall of Fame outfield in Ed Delahanty, Billy Hamilton, and Sam Thompson, the future looked promising in Philadelphia. But Connor refused to sign the $1,800 contract tendered for the 1893 season by the club’s cash-strapped management. Consequently, the Phillies traded him back to New York in exchange for journeymen Jack Boyle and Jack Sharrott, plus cash.[29]

Despite reaching the age of 36 by midseason, the durable Connor played the entire 135-game Giants schedule. And like most National League batsmen, he was a beneficiary of 1893 rule changes that moved the pitching distance back to 60 feet 6 inches and eliminated the pitcher’s box. But numbers that once might have placed Connor in the top echelon – 105 RBIs, 11 home runs, and .863 OPS – were not particularly noteworthy given the offensive explosion of that season. Connor did, however, manage one extraordinary feat. As uncovered by biographer Roy Kerr, he hit four of his 11 1893 home runs batting right-handed.[30] The Giants, meanwhile, finished a nonthreatening fifth, 19½ games behind pennant-winning Boston. Connor got off to a decent (.293 in 22 games) start for the 1894 Giants. But on May 17 he was benched by manager John Montgomery Ward in favor of young Jack Doyle. Now faced with the prospect of only limited playing time, Connor sought and was granted his release by de facto Giants boss Talcott.[31] He joined the St. Louis Browns, formerly a four-time (1886-1889) American Association pennant-winning team but now reeling under the lash of madcap owner Chris von der Ahe. In 99 games Connor posted solid numbers for the Browns, batting .321 with 25 triples, seven homers, and 79 RBIs.[32] But the team was a noncompetitive eighth-place finisher, 35 games behind the champion Baltimore Orioles.

The 1895 season was another dreary one in St. Louis. But not for Roger Connor personally. Playing in only 104 games, his season punctuated by a July 20-to-August 30 hiatus in Waterbury, Connor hit .327 with respectable on-base percentage (.421), slugging (.504), and OPS (.924) figures. But his teammates – including brother Joe Connor in a two-game tryout[33] – were of little help and the Browns finished a wretched 39-92 (11th place) for the season. With his 39th birthday on the horizon the next spring, Connor still wanted to play ball. So he returned to St. Louis for the 1896 campaign, perhaps the unhappiest of his long baseball career. The Browns were still lousy and after a 16-34 start, manager Al Buckenberger was dismissed (reportedly for drunkenness). Von der Ahe himself managed the next two games (1-1) before Connor was induced to take the reins. Regrettably, Roger’s gifts did not include leadership ability and his reserved, gentlemanly demeanor left him ill-suited for the demands placed upon him. Exercising the manager’s obligation to challenge umpiring decisions that went against the Browns made him particularly uncomfortable. On this score, Connor would play 1,998 major-league games without ever being ejected. Worse yet, the new skipper had little talent to call upon. Thus his managerial stint yielded predictable results: an 8-37 record encumbered with a 15-game losing streak when he resigned in July, leaving shortstop Tommy Dowd the task of guiding the Browns home to their second consecutive 11th-place finish. As for his playing performance, Connor was an improvement over most of his erstwhile charges. In 126 games, he batted a respectable .284 with 11 home runs, fourth most in the league. He also led league first basemen in fielding percentage (.986) once more.

Connor’s 18th and final big-league season was an abbreviated one. He was batting only .229 in 22 games when manager Dowd publicly criticized his fielding and benched him. His pride wounded, Connor asked for and received his release from Browns boss Von der Ahe, bringing his major-league career to a close. By any measure, it had been an exceptional one. In just under 2,000 games, he had compiled 2,542 base hits and a .323 lifetime batting average.[34] His 138 career home runs were the major-league standard for more than the next 20 years. And Connor’s 233 triples remain the most ever hit by an exclusively 19th-century player. In addition to his hitting prowess, augmented by over 1,000 walks (against only 453 strikeouts), the big slugger had transformed himself from an erratic left-handed third baseman into a top-notch first sacker, four times a league leader in fielding percentage for the position. And from the 1886 season on (when statisticians started keeping track of such things), he had been credited with 244 stolen bases. But perhaps more important than his tangible achievements, Roger Connor had been a rock, the durable, steadfast, and unflappable anchor of the world-championship teams that established major-league baseball in New York, the one market indispensable to the game’s prosperity.

After his release by St. Louis, Connor returned to his family in Waterbury. But baseball remained irresistibly in his system. Only shortly after he had arrived home, he was in uniform for the Waterbury Pirates of the Connecticut State League, the vibrant minor-league circuit that had recently been established by his old friend Jim O’Rourke. A month later Connor moved up to the faster-paced New England League, signing on as player-manager of the Fall River Indians and bringing brother Joe along with him. In addition to manning first base, Roger assumed administrative tasks (game scheduling, player recruitment, salary disbursement, etc.) which distracted him from performance on the field. Still, he managed to hit .287 while guiding Fall River to a 20-27 record during his time as team leader.[35]

The following season, the Connor brothers returned to the Connecticut State League where Roger assumed total control of the Waterbury franchise. With Roger and Joe on the infield corners, Angeline handling the gate receipts and ten-year-old Cecilia making herself useful around the grounds, the Waterbury operation was a true family affair. And a successful one, too, with Waterbury capturing the league pennant by a hair (.002 in league standings) over New Haven. That winter Connor came to the aid of league President O’Rourke, providing the support that proved decisive in thwarting a hostile takeover bid by the rival New England League.[36] Renaming his team the Rough Riders for the 1899 season, Connor seemed to regain the form of his youth, batting a league-leading .392. But even the midseason recruitment of the fabled Louis Sockalexis would not be enough for Waterbury to repeat as league champion. At season’s end, Connor’s 52-43 team was obliged to relinquish the crown to New Haven.

Connor continued as player-owner in Waterbury until July 1901, when, dissatisfied with both his team’s play and the level of fan support, he sold the franchise to local businessman George Harrington. But the now 44-year-old Connor remained unable to resist the diamond’s call. He completed the 1901 season at first base for former rival New Haven, batting a combined .299 in 107 Connecticut State League games. For the 1902 season, Connor organized a team in Springfield, Massachusetts, that was admitted for play in the Connecticut State League.[37] That June he earned his first and only ejection from a professional baseball game. His offense: a pummeling of old National League foe Tommy Tucker for having thrown Joe Connor to the ground during a game in Meriden. Donning eyeglasses in 1903, Connor squeezed out one more season, batting .275 in 75 games for Springfield. Shortly after the schedule was concluded, he sold the club and retired from professional baseball at the age of 46.

Prudent investments and a modest lifestyle afforded Roger Connor a comfortable retirement. In 1907 Cecilia married a Waterbury pharmacist, James Colwell, and, in time, provided her father five grandchildren to dote upon.[38] And Connor continued to play baseball intermittently for the Waterbury Elks Club and other local nines until an injury on the field persuaded him to hang it up for good in the fall of 1910. He was then 53 years old. In 1914 Connor was appointed inspector of schools in his hometown, a position that placed him in charge of building maintenance and the janitor corps. He and Angeline also began wintering in Florida. Captivated by the climate, Connor later joined the horde of investors who fueled the Florida real-estate boom of the early 1920s. The crash of that market and property damage caused by a monster Miami hurricane in 1926 inflicted serious blows on the Connor family finances. Ultimately, he and Angeline were obliged to sell their home in Waterbury and move in with the Colwells. Nevertheless, the Connors continued their annual winter trip to Florida. There, Angeline fell ill in February 1928. Returning home to recuperate, she was stricken by a heart attack and died on St. Patrick’s Day, about age 67. Roger was devastated by the loss and soon his own health began to fail. In 1929 cancer of the larynx necessitated the removal of most of his voice box. Late the following year, he underwent prostate surgery. On January 4, 1931, sepsis from the operation and chronic heart disease brought Roger Connor’s life to an end. He was 73 years old. After a funeral Mass at St. Margaret’s Church, he was laid to rest beside Angeline in an unmarked grave in Waterbury’s Old St. Joseph’s Cemetery. He was survived by daughter Cecilia Connor Colwell and family, sister Mary Connor Slattery, and brothers Joseph and Matthew.[39]

In the years that followed, the memory of the great 19th-century slugger grew dim. When the National Baseball Hall of Fame opened its doors in the late 1930s, former teammates Buck Ewing (1939) and Jim O’Rourke (1945) got early calls. Tim Keefe and John Montgomery Ward joined them in 1964 while Mickey Welch was inducted in 1973. But it took the historic April 8, 1974, homer of Hank Aaron to stimulate interest in one-time major-league career home-run leader Roger Connor. Two years thereafter, long-deserved recognition was finally accorded him by the Veterans Committee. At the August 9, 1976, induction ceremony, the plaque that enshrines the memory of Roger Connor was acknowledged by grandson Francis Colwell. Almost 100 years earlier, the New York Clipper profile that introduced Connor to baseball fandom at large had stated that “Connor’s honorable and straightforward conduct and affable and courteous demeanor towards all with whom he is brought into conduct have won him deserved popularity both on and off the ball-field.”[40] Those words would have been equally apropos if spoken at his funeral more than 50 years later. For Roger Connor was constant, an exceptional ballplayer, and an even better man.

December 9, 2011

Sources

In addition to the sources expressly cited in the Notes below, the following works were consulted during the preparation of this profile:

Dennis Corcoran, Induction Day at Cooperstown: A History of the Baseball Hall of Fame Ceremony (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2011).

David L. Fleitz, Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Forgotten Members of the Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2004).

Mike Roer, Orator O’Rourke: The Life of a Baseball Radical (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005).

Total Baseball, 7th edition, John Thorn, et al., eds. (Kingston, New York: Total Publishing Inc., 2001).

The writer is indebted to Dana Lucisano of the Silas Bronson Library in Waterbury and Connor biographer Roy Kerr for their generous assistance in the preparation of this profile.

[1] The biographical data contained herein are derived from various US censuses; the Roger Connor files at the Giammati Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York, and the Silas Bronson Library, Waterbury, Connecticut; the reminiscences of Connor granddaughter Margaret Colwell, published in the Waterbury Republican, August 8, 1976, and, especially, Roy Kerr’s informative and comprehensive biography, Roger Connor, Home Run King of the 19th Century (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2011). The Connor children were Hannah (born 1853), Mary (1856), Roger (1857), Julia (1860), Ellen (Nellie – 1863), Daniel (1866), Dennis (1868), Matthew (1870), Murtagh (1872), and Joseph (1874). Julia and an infant whose name is lost to history did not survive childhood.

[2] Marty Connor and Catharine Sullivan (who emigrated in 1845) were married by Father Michael O’Neil in Waterbury on November 8, 1852. Waterbury Vital Records, Vol. IV, p. 33. Murtagh Connor’s first name (after Saint Murtagh, a sixth-century Irish bishop) was also mangled by US census takers who recorded him as Murtie Connor in 1860 and as Murta Connor ten years thereafter (while listing a 4-year-old son as Murtaugh Connor). After Murtagh Connor’s death in September 1874, his first name was usually given as Mortimer, an Anglicization that debuted on the passenger list of the ship that brought him to America. The short interval between the arrival of Murtagh Connor and his absorption into the Waterbury community leads Roy Kerr to suspect that his situation, including marriage, was prearranged by local relatives or friends.

[3] As related by Roger’s granddaughter Margaret Colwell in the Waterbury Republican, August 8, 1976.

[4] Kerr, 11

[5] Years later, New Bedford manager Frank Bancroft expressed regret about releasing Connor, describing it as one of the worst errors that he ever made during a long baseball career. Sporting Life, May 4, 1897.

[6] Kerr, 21

[7] Statistics cited herein are taken from www.Baseball-reference.com.

[8] The headstone that she and Roger share at Old St. Joseph’s Cemetery gives her name as Angelina Meir. But Angeline Mayer (daughter of Jacob and Apoline Mayer) is the name handwritten in 1870 census records.

[9] According to Margaret Colwell in the Waterbury Republican, August 8, 1976.

[10] Some sources date the marriage to 1882 while granddaughter Margaret Colwell provided a June 15, 1883, marriage date to the Waterbury Republican in 1976. Of overriding concern to Roger, he was not married in a Catholic church – Angeline was the daughter of non-Catholic German immigrants.

[11] Organized Baseball’s first grand-slam home run was hit by Charley Gould of the Boston Red Stockings in an 1871 National Association game.

[12] New York Clipper, October 2, 1880

[13] Troy had released Dan Brouthers after a handful of games in 1880. In 1882 Brouthers captured the first of his five major-league batting titles, hitting .368 for Buffalo.

[14] New York and Philadelphia had been expelled by National League President William Hulbert for failure to fulfill late-1876 season road game commitments.

[15] Technically, the New York teams in the National League and the American Association were operated by the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, Day’s corporate alter ego.

[16] Team owner Day had intended the Gothams to be his showpiece nine.

[17] For more detail on the gutting of the Mets, see the BioProject profile of John B. Day. The depleted Mets limped to a seventh-place finish in the American Association in 1885. Two months after the season was over, the club was sold to entrepreneur Erastus Wiman, who promptly relocated it to his amusement grounds on Staten Island.

[18] New York manager Mutrie is commonly credited with coining the nickname Giants, but SABR 19th Century Committee Chairman Peter Mancuso suspects that it may originally have been coined by a New York Evening World sportswriter. See the BioProject profile of Jim Mutrie, pp. 7-8. There is no controversy, however, regarding the chief inspiration for the new team name. Although there were several 6-footers on the 1885 New York team, the 6-foot-3, 220-pound Connor was the only true giant on the Giants.

[19] According to the Connor family tree posted on www.Ancestry.com, Lulu Connor was born in September 1886. Other accounts place her birth as sometime in 1888. Margaret Colwell said the somewhat exotic Lulu was “a fashionable name at the time.” Waterbury Republican, August 8, 1976. But Connor’s biographer suggests that the name might have been inspired by Lulu Hearst, a novelty performer briefly popular in the mid-1880s. See Kerr, 88-89.

[20] Baseball-reference.com and other compendiums disregard the walk-equals-hit anomaly of 1887 and calculate the season’s statistics the orthodox way. Using this methodology, Connor’s 1887 batting average adjusts to a subpar .285.

[21] Waterbury Republican, August 8, 1976. Sadly unbeknownst to her husband, Angeline Connor had been taking religious instruction and planned to be baptized with Lulu on the child’s first birthday. Sometime after her daughter’s death, Angeline converted to Catholicism. She later took an active role in the affairs of St. Margaret’s Church, the parish of the Connor clan.

[22] For more on the ballpark travails of the 1889 New York Giants, see the BioProject profile of Manhattan Field, aka the New Polo Grounds.

[23] 1890 Spalding Guide

[24] Sporting Life, January 8, 1890

[25] Connor’s remarks were published in Sporting Life, August 8, 1890. Such an outburst was totally out of character for him. As noted years later, Connor “was not a talkative player. … He criticized seldom or never, and was always ready with a word of encouragement.” The Sporting News, January 5, 1931.

[26] Of the 1889 world champion New York Giants regulars, only fading hurler Mickey Welch and outfielder Mike Tiernan remained in Day’s employ. Except for John Montgomery Ward, playing manager of the new circuit’s team in Brooklyn, the others all joined the New York Players League team.

[27] Chicago Tribune, November 22, 1890

[28] Bernard J. Crowley, “Roger Connor,” in Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: SABR, 1996).

[29] Baseball-reference.com

[30] Kerr, 122-123. The home runs were hit off left-handers Jack Sharrot (2), Duke Esper, and Ed Killen.

[31] Back in 1886, Wall street financier Talcott had taken up a collection among fellow grandstand fat cats and then presented Connor with a gold watch commemorating his titanic Polo Grounds blast, as recalled by sports columnist John Kiernan in the New York Times, January 7, 1931. After his release from the Giants on June 1, 1894, Connor expressed appreciation for Talcott giving him his unconditional release so that Connor could prolong his career with the Browns. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 4, 1894.

[32] Including 22 games with the Giants, Connor batted a combined .316, with 8 homers and 93 RBIs during the 1894 season.

[33] Joe Connor went 0-for-7 in two games for the 1895 St. Louis Browns. He would not get another chance in the major leagues until the 1900 season.

[34] If the walks-equals-hits aberration of the 1887 season is eliminated, Connor’s lifetime hit total and batting average are reduced to 2,467 and .316, respectively.

[35] Connor’s post-major-league career is chronicled in Chapter 7 of Roy Kerr’s biography of Roger Connor, the primary source for this aspect of the Connor profile.

[36] Washington Post, March 2, 1899

[37] The admission of a non-Connecticut team precipitated the change of the circuit’s name to the Connecticut Valley League.

[38] Cecilia’s first child was named Roger in her father’s honor. Another grandchild, Margaret Colwell (1914-1987), would later provide the affectionate, if factually inexact, recollections that supply much of what is known about the early life of Roger Connor.

[39] The Depression did not spare Connor’s family. In death, Roger left a $650 debt to the hospital and funeral home, an obligation that took his daughter Cecilia years to pay off. Thus, there were no funds available for a graveyard memorial for Roger and his wife in 1931. Some 70 years later, a fund-raising campaign spearheaded by Waterbury librarian Mike DiLeo and former Connecticut state Senator Robert Dorr ameliorated the situation. The grave of Roger, Angeline, and grandson Roger Colwell is now marked by a handsome headstone. Waterbury Republican-American, July 1, 2001.

[40] New York Clipper, October 2, 1880

Full Name

Roger Connor

Born

July 1, 1857 at Waterbury, CT (USA)

Died

January 4, 1931 at Waterbury, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.