Ron Kline

Ron Kline is one of a number of professional athletes who entered politics after their professional athletic careers came to a close. The most notable baseball player turned politician is Jim Bunning, US Senator from Kentucky (1999-2011), though others (Vinegar Bend Mizell and Fred Brown, for instance) also served in political office.1

Ron Kline is one of a number of professional athletes who entered politics after their professional athletic careers came to a close. The most notable baseball player turned politician is Jim Bunning, US Senator from Kentucky (1999-2011), though others (Vinegar Bend Mizell and Fred Brown, for instance) also served in political office.1

Ron Kline became mayor of his hometown of Callery, Pennsylvania.

We count at least five other mayors who have major-league baseball backgrounds, all in Latin America: Bobby Avila (Veracruz, Mexico), Aurelio Lopez (Tecamachalco, Mexico), Raul Mondesi (San Cristobal, Dominican Republic), Magglio Ordonez (Sotillo, Venezuela), and Melido Perez (San Gregorio de Nigua, Dominican Republic).2

Callery is a small borough in Butler County, Pennsylvania, located between 25 and 30 miles north of Pittsburgh. Its population at the time of the 2010 census was 394, of which 275 were voting age. A former railroad junction, the largest enterprise in Callery in 2018 is the metal processing firm, Herr-Voss Stamco.

Ronald Lee Kline was born in Callery on March 9, 1932. His parents were Henry Rea and Fern Rea. Fern Mae Kline was born to railroad engineer John Wesley Kline and his wife Floda Zenobia (Bowser) Kline. She had two older brothers, Leroy and Ross. Fern Kline married Henry J. Rea, born in nearby Connoquenessing Township in 1912. It appears that the two were married at some point in 1943, while Henry was in the United States Army.3 Young Ron was an only child.

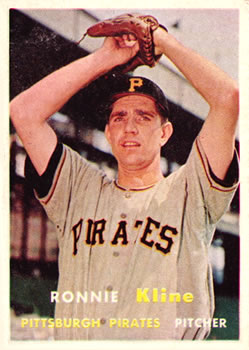

Kline played major-league baseball for 17 seasons (1952-1970, with two years spent in the Army during the Korean War.) A right-hander, Kline was 6-foot-3 and listed at 205 pounds. A starter who became a reliever, Kline won 114 big-league games and recorded a career 3.75 earned run average. He pitched for nine different major-league teams, but of his 736 appearances most were for his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates (eight seasons, 288 games) and the Washington Senators (four seasons, 260 games). Slightly more than half his games were in the American League.

He was far from a fearsome batter. Rather, he was something of an advertisement for the designated hitter. In 491 at-bats, he struck out 221 times, and had a lifetime batting average of .092. In 548 plate appearances, he drove in 14 runs. Perhaps his best contribution came from the sacrifice hit; he is credited with 39 sacrifices. Though he pitched into June 1970, his last base hit was on April 17, 1966. His next 31 at-bats were hitless, including 16 with the Pirates in 1968.

Kline attended Evans City High School and was notably vice president of the Senior English Club. He also lettered in football and track, but not baseball. Nonetheless, his talents as a pitcher were known locally, playing for a town team. Ron’s daughter Vicki says, “My grandma’s brothers, Uncle Ross and Uncle Baldy were ballplayers. They played for a team in Callery. A lot of Dad’s friends from Callery played on the team, too. We used to call the field ‘Cow Patty Stadium.’ It was just a farmer’s field. When they weren’t playing ball there, the cows came through and kind of dirtied it up a tad.”4

On graduation from his school in May 1950 he was signed to a pro contract by the Pittsburgh Pirates. His widow Dorothy (Wilson) Kline reported to SABR in February 2004 that Ron had been signed by Bill Hulton. Kline himself said, “I was signed out of tryout camp at Forbes Field in 1950. Pie Traynor signed me. The Pirates sent me to Bartlesville, Okla.”5 Hulton was apparently a semipro football coach who had arranged the tryout with the Pirates.6

Dorothy Wilson came from Mars. Mars was another borough in Butler County, only a very few miles from Callery. They married on February 22, 1953. Dorothy and Ron had four children, all girls—Vicki, Kimberly, Tamara, and Melanie.

The Bartlesville Pirates played in the Class-D K-O-M League (Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri); in the partial season he spent there, Kline worked in 12 games, starting eight of them. He put up a 5-2 record with a 3.81 ERA and was invited back for his first full season of pro ball in 1951. That year, he was an All-Star, his 18-4 record leading the league in wins and winning percentage. His 208 strikeouts in 209 innings also led the league. He pitched 21 complete games. Kline still had time to start four games for the Double-A New Orleans Pelicans (1-3, 3.86).

It was quite a leap to the big leagues, Class D to the Pittsburgh Pirates, but Kline debuted in the majors on April 28, 1952. It was far from an auspicious start to a career: he was 0-7 with a 5.49 ERA and he walked more than twice as many batters as he struck out (66-29). But the 1952 Pirates needed someone to pitch. They finished in last place with a record of 42-112. Murry Dickson (14-21) was their leading pitcher. No one else had more than seven wins. Kline had 11 starts and relieved in 16 other games. Optioned out for a while on July 10, he also worked in 13 Carolina League games, pitching Class-B ball for the Burlington-Graham Pirates (3-6, 3.51).

Kline didn’t win another professional ballgame until 1955. Perhaps ruminating his 0-7 start, he spent the years of 1953 and 1954 in the United States Army during the Korean War. He was stationed at Camp Breckenridge in Kentucky and at Aberdeen, Maryland. He played some baseball at Breckenridge, and for a semipro team about an hour from Aberdeen. “When I came out of there, Branch Rickey sent me to Basillon, Mexico, for five months. When I came back, I had some sort of an arm problem for about a month-and-a-half to two months in ’55. He sent me to the Dominican the next winter and that seemed to fix it up.”7

That makes it sound as though he didn’t pitch much for the Pirates in 1955, but he did pitch most of the season, throwing 136 2/3 innings in 36 games. He lost his first two starts, in April, running his career record to 0-9 but then he shut out the St. Louis Cardinals, 7-0, in the second game of the May 1 doubleheader. He allowed seven hits and didn’t walk a batter. It was one of eight shutouts in his career. Five days later, he beat the Giants at the Polo Grounds, 3-2. At season’s end, he was 6-13 (4.15). It was during the winter of 1955-56 that he worked in the Dominican Republic, developing two new pitches—a slider and the knuckleball.

In 1956, Kline was second on the Pirates in wins (14). He started 39 games and held a 3.38 earned run average. He worked in a career-high 264 innings. Kline’s record for the seventh-place team, however, was 14-18, leading the National League in losses. He also led the league with 10 wild pitches, but he struck out 125 batters and only walked 81.

The 1957 season started disastrously. Kline was again 0-7, and that was just through the end of May. His ERA, though, was 4.02. Two of the losses had been 1-0 games, and another was a 3-1 defeat. He won a couple of games in early June, but then lost another seven straight decisions from June 14 through July 26. The Pirates weren’t scoring runs for him, and he was stuck with a 2-15 record. In his first 20 starts, the Bucs scored 27 runs.8 Then Kline decided to get rid of his knuckler “because it didn’t knuckle,” wrote Les Biederman. He quoted Kline, “I can’t say too much against the knuckleball. The knuckler helped me in 1956 and maybe I depended on it too much this season. But it didn’t seem to do anything and the batters were waiting for me to throw it. By junking it, I’ve found I’ve been stronger in the late innings and my fast ball is that much more alive.”9 He reeled off six wins in a row, and finished a much more respectable 9-16 (4.04).

Kline pitched two more seasons for the Pirates in the 1950s, before a return in 1968. In 32 starts in 1958, he was 13-16, the 16 losses again leading the league. His earned run average was 3.53. In 1959, he was 11-13 (4.26). On December 29, 1959 he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for Tom Cheney and Gino Cimoli. The Pirates were looking for a hitter and Cimoli was the key for them; Pittsburgh GM Joe L. Brown expressed regret at parting company with Kline. For his part, Kline had expressed some frustration that he wasn’t being used as much in 1959.10 And he’d said as much on the air, which may have prompted the Pirates to deal him.11

The next year, 1960, the Pirates went on to win the World Series.

In 1960, Kline appeared in 34 games for the third-place Cardinals. Of those 34 games, he started exactly half—17 games—and all of those starts were in the first half of the season. From July 4 on, he worked only in relief. He was 3-7 with a 5.73 ERA as a starter. Working as a reliever, his ERA ticked up to end at 6.04. His record was 4-9; three of his four victories were against the Pirates.

Right around the turn of the year, Kline suffered a hunting accident when a brass shell exploded lodging two pieces of brass in his right eye and one in his left eye. Fortunately, the three fragments were removed without damage to his eyesight.12

Just before the 1961 season began, the Cardinals cut Kline from their roster on April 9. They’d wanted to send him to the minors, to Portland, but he said he wouldn’t report.13 The next day, they sold him to the Los Angeles Angels for what Cardinals GM Bing Devine said was “an undisclosed amount that is close to the waiver price.”14 Based on his past performance, the Angels got what they should have expected; Kline went 3-6 (4.90) in 12 starts and 14 relief appearances. On August 10, he was sold to the Detroit Tigers in what was announced as a “straight cash deal.”15

Though he was hammered in his first start, seeing six runs scored and not able to complete the second inning, he threw a shutout his second time out. In his month and a half with the Tigers, he went 5-2 with a 2.72 ERA.

Kline spent the next season with the Tigers, too. The 1962 season was the first in which he began to do the bulk of his work as a reliever. He started four games during a stretch in August and lost three of them. Overall, he was 3-6 (4.31). After the season, he joined the Tigers on an exhibition tour to Japan, and at least briefly contemplated playing there—but wound up signing again with Detroit.16

During spring training 1963, he was sold to the Washington Senators. Again, it was an economical deal, “slightly over the waiver fee of $25,000.”17 For the next four seasons, he was a Senator. They got themselves a bargain. Only in 1966 did another Washington pitcher work in more games. Kline averaged 65 appearances a year, working steadily and working all but one of the games out of the bullpen. For all four years, while the Senators never featured higher than eighth place, Kline kept his earned run average under 3.00, a 2.54 ERA over the course of the years. He won 26 and lost 25, and saved 83 games. In 1965, his 29 saves led the American League.

Right from the start of his time with the Senators, speculation surfaced that Kline was using a spitter, something that had been talked about for some time.18 He didn’t specifically deny it, but at the very least took advantage of the reputation: “If they think I’m using the spitter, let them think so. That’s the edge they’ve giving me when I’m out there, and I’m grateful for it.”19 Pirates GM Brown once cracked, “The spitter is his best pitch and he hasn’t even used it.”20

After the 1964 season, Kline was part of a group of major leaguers who went on a goodwill State Department visit to Colombia, Panama, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic.21

After the 1966 season, Minnesota Twins president Calvin Griffith felt he needed a much stronger bullpen to contend in 1967. On December 3, he traded both Bernie Allen and Camilo Pascual to the Senators for Ron Kline. Kline said, “I hate to leave Washington because Gil Hodges has always treated me so well. But I’ll be with a contender and I’ve never been in in a World Series.”22

The Twins finished in second place, as they had the year before, though only after losing the final two games of the season to the Impossible Dream Boston Red Sox. Kline’s ERA declined to 3.77, but his won/loss record had been spectacular. He was 7-0 coming into those final two games in Boston. Relieving in the bottom of the sixth of the September 30 game, the first batter Kline faced was George Scott, who homered to give the Red Sox a 3-2 edge. In the seventh, with one out and a man of first base, Kline fielded a routine comeback to the mound that should have been an easy double play—but the Twins’ shortstop dropped the ball and both runners were safe. Jim Merritt replaced Kline, and Carl Yastrzemski hit a three-run homer off him. Kline lost that penultimate game, and finished the season 7-1. The two teams thus had identical 91-70 records. The Red Sox won the deciding October 1 game.

In 1968, Kline was back home pitching for the Pirates. They had traded Bob Oliver to the Twins on December 2, 1967. Kline lost his first decision for the Pirates but then reeled off 10 wins in a row. He shared closing duties with Roy Face, finishing with a 12-5 record, seven saves, and a career-best 1.68 ERA, over the span of 112 2/3 innings. In August, none other than Roberto Clemente had asked, “How come you don’t give Ron Kline the publicity he deserves? Kline has kept us from dropping out of sight.” The reporter he asked said that Kline typically did not give more than “yes” or “no” answers. So Clemente said he’d do the interview. Part of the exchange:

Clemente: “Why you better relief pitcher than starter?”

Kline: “I have better control now than I had as a starter. And I have a good knuckler now. I can throw strikes almost any time I want to.”23

Kline enjoyed overseas travel, but after the 1968 season, when American involvement in Vietnam was approaching its peak, he took time during the late fall to take another kind of trip. He joined Ron Taylor of the Mets and Mets’ publicity director Arthur Richman, and the three toured hospitals in Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, Guam, Okinawa, and Japan visiting with wounded servicemen on a trip sponsored by the USO.24

After his superb season in 1968, his baseball career somewhat rapidly wound down—though in February 1969 he began another career when he bought a tavern in his hometown of Callery. He operated it for a number of years as Ronnie Kline’s Bullpen. It has had a few different incarnations, but in 2018 is called Milano’s Pizza.

In 1969, Kline pitched for three teams. He started the season with the Pirates and worked in 20 games, but was 1-3 with an ERA of 5.81. On June 10, he was traded to the San Francisco Giants for left-handed pitcher Joe Gibbon (who did very well for the Pirates the rest of the year). Kline was, however, 0-2 for the Giants with an ERA of 4.09 in 11 innings over seven games. After less than a month, he was sold to the Boston Red Sox for the $25,000 waiver price on July 5. For the Red Sox, Kline appeared in 16 games and was 0-1 with a 4.76 earned run average. In early September, he acknowledged, “I’ve had a bad year; the breaking pitches don’t break any more and I’ve been clobbered.”25 He talked about going to Venezuela and working over the winter to get back his knuckleball.

After the season the Red Sox sold his contract outright to Louisville, to free up roster space, but they invited him to spring training in 1970. He came early, and had worked hard to get in shape. On March 31, however, the Red Sox gave him his unconditional release.

Kline was now a free agent, and on April 30, the Atlanta Braves signed him to supplement their bullpen. He worked in three May games and two in June, for a total of 6 1/3 innings. He earned a save in his first outing, and bookended the five outings with another scoreless inning, but his ERA was 7.11, and on June 25 the Braves asked for waivers for the purpose of giving him his unconditional release.

Kline pitched for a while for the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League, appearing in 15 games. He was 4-0 with a 3.27 ERA.

The following February, Kline announced his retirement from baseball and his candidacy as a Republican for the Butler County Register and Recorder. He was unsuccessful in that race, but later served as mayor of Callery for a number of years.

Kline pursued a number of other occupations. His daughter Vicki said, “He sold cars for a while at Tom Henry Chevrolet in Bakerstown. At one point during his career he owned a car dealership in Harmony Village. JORON’s. It was one of his childhood friends named John and him. They sold Chrysler Plymouths. What he actually wanted to do with that area was put a McDonald’s in, but none of the banks would finance a McDonald’s. They said it was a waste of money. McDonald’s were kind of brand new and they didn’t think it was a worthwhile investment. Just think!”26

Vicki added that he coached baseball locally for a while, working with an age group that was older than Little League.

Ron Kline died in Callery, at home, on June 22, 2002. He had suffered from diabetes and congestive heart failure. His daughter explained, “He had neuropathy in his legs. It was just like his body was wearing out. The last time he went into the hospital, they put him on a ventilator and they brought him home three times. I couldn’t make the decision to take him off. My mom couldn’t either. He came out of it, and told them he didn’t want anything. He just wanted to go home. We got him home and about 12 hours later he passed away.”

Ron’s daughter also recalls, “The Callery Carnival was on at that point, and so all the fire trucks from the parade came down past the house blowing their horns for him. That was really nice.

“He really liked Callery. His heart was here. This is where he wanted to be. Lifelong friends. This is where he was at home, He would go to spring training, and play in whatever city he was in. But he always wanted to be here.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Skylar Browning and fact-checked by Alan Cohen. Thanks to Vicki Sayti for a careful reading of the first draft.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Kline’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Basketball saw Bill Bradley serve as U.S. Senator from New Jersey from 1979-1997. Football has produced at least six Members of Congress in the U.S. House of Representatives: Jack Kemp, Steve Largent. Tom Osborne, Jon Runyan, Heath Shuler, and J. C. Watts. Depending on one’s definition of athlete, we might like to note Governors Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jesse Ventura.

2 Basketball has also produced two mayors of major American cities: Dave Bing (Detroit) and Kevin Johnson (Sacramento.)

3 The basis for this deduction is that Connoquenessing city directories in 1939 show Henry J. Rea as a shearman working for the steel mill in Butler, ARMCo and in 1942 as a catcher for ARMCo. In neither year did he have a listed spouse. In Social Security data compiled after Fern Rea’s death (August 25, 2003), she is listed as Fern Mae Kline in August 1941 but as Fern Kline Rea in January 1944. Some 30 years later, her 1975 listing has her as Fern Mae Rea. Henry Rea enlisted in the Army in 1943 at Fort Meade. He was the son of an oil producer, Silas Amberson Rea and his wife Myrtle Sarah (Stover) Rea. Henry had an older brother, Thomas, who was an oil driller at the time of the 1930 census. Connoquenessing is located about 12 miles from Callery. According to Vicki Sayti, Fern Rea worked for a while at Austin Bleach, in Mars.

4 Author interview of Vicki Sayti on February 19, 2018.

5 Chuck Greenwood, “Kline Trades Pitching for Politics in his Hometown,” Sports Collectors Digest, April 16, 1999: 50. Dorothy Kline’s information was supplied in response to a questionnaire sent out by SABR’s Scouts Committee.

6 Neal Russo, “Ron Kline Here, Thinks His Radio Comment Led to Trade to Cardinals,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 4, 1960: C4. Les Biederman confirmed the Traynor signing, crediting both Traynor and scout Charlie Muse. Les Biederman, “Ron Kline On Verge of Stardom for Bucs,” Pittsburgh Press, March 17, 1957.

7 Chuck Greenwood. The arm problem cropped up in August and he lost about three weeks.

8 Les Biederman, “Buc Fans Hail Groat, Over .300, as Most Underrated Shortstop,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1957: 20.

9 Les Biederman, “Ron Kline,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1957: 30.

10 Associated Press, “Pirates Trade Ron Kline for St. Louis Duo,” Advocate (Baton Rouge), December 22, 1959: 27.

11 Neal Russo. Kline worked during the offseason as a junkman, running a trash collection business with two others.

12 “Kline in Hinting Accident, But Escapes Serious Injury,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1961:

13 Earl Lawson, “At 36, Kline’s Going Strong,” Cincinnati Post & Times Star, May 25, 1968: 11.

14 UPI, “Cardinals Sell Kline to Angels,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), April 11, 1961: 11.

15 UPI, “Tigers Buy Ron Kline,” Boston Daily Record, August 11, 1961: 54.

16 “Kline Inks Tiger Contract; Talked of Playing in Japan,” The Sporting News, January 26, 1963: 32.

17 Merrell Whittlesey, “Senators Buy Ron Kline to Bolster Bullpen,” Evening Star (Washington D.C.), March 18, 1963: 15.

18 Merrell Whittlesey, “Kline’s Spitter Topic of Day,” Evening Star (Washington D.C.), March 19, 1963: C5.

19 Shirley Povich, “Rescue Artist Kline Soothes Nat Headache,” Washington Post, August 17, 1963. He did later deny it, calling it an old wives’ tale. See Bob Addie, “Ron Kline,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1965: 27. Umpire Hank Soar said the umpires had been watching him and didn’t ever see him throw one. Max Nichols, “With or Without Spitter, Kline Is a Sharp Reliever,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1967: 6. Later, Kline let slip that he just might have thrown one earlier on. “I don’t throw it anymore,” he said in August 1968. Les Biederman, “While Hitters Look for Spitter, Kline Rolls Up Victories,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1968.

20 Earl Lawson.

21 Bob Addie, “Kline Pacing Cards On Table – He Wants Pay Hike From Nats,” Washington Post, November 14, 1964.

22 “Kline Views Twins’ Trade As Chance to Reach Series,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1966: 26.

23 The reporter is not identified on the story itself, but the piece is placed next to a story by Les Biederman and appears on page 18 of the August 17, 1968 Sporting News.

24 Les Biederman, “Kline Brings back Messages From Wounded GIs,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1968.

25 Merrell Whittlesey, “Wins Secondary in Winter League,” Evening Star (Washington D.C.), September 7, 1969: 82.

26 Vicki Sayti interview.

Full Name

Ronald Lee Kline

Born

March 9, 1932 at Callery, PA (USA)

Died

June 22, 2002 at Callery, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.