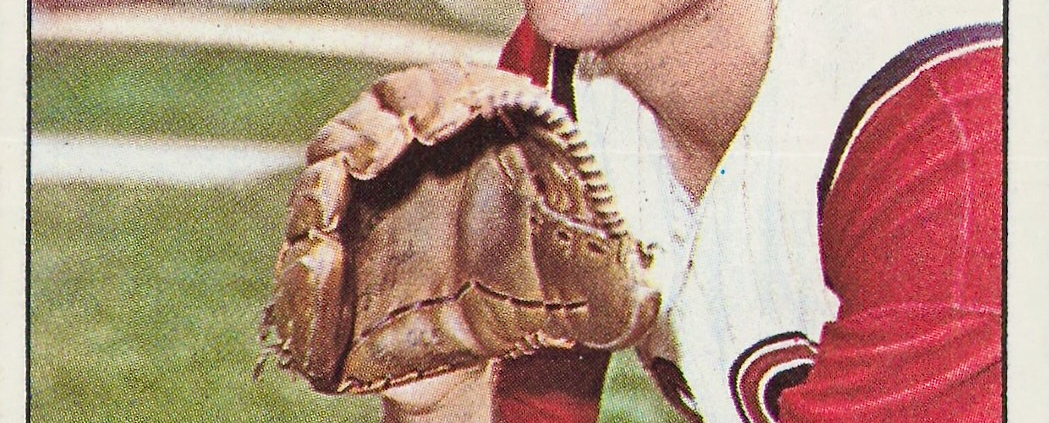

Ted Davidson

Her first words on the phone to the police were, “My name is Mary, and I’ve shot a man.”1

Her first words on the phone to the police were, “My name is Mary, and I’ve shot a man.”1

It was March 9, 1967. Left-hander Ted Davidson, just 11 days into spring training and with his big break in the Cincinnati Reds bullpen imminent, lay bleeding behind a Tampa bar. His blonde assailant had fired four shots—two of which pierced the pitcher—before fleeing the scene. The incident attracted national attention and harked back to Bernard Malamud’s 1952 novel The Natural, in which young pitcher Roy Hobbs is felled by a mysterious triggerwoman—only Davidson’s shooter was his estranged wife.

Davidson, who was going into his third year with the Reds, recovered and made it back to the majors that September. However, he lasted for just part of one more season at the top level; a year after that, he was out of baseball. He just wasn’t the same after the shooting.2

***

Thomas Eugene Downing—“Ted” was an acronym—was born in Las Vegas, Nevada, on October 4, 1939. He was the first of two children born to Tommy Clifton Downing, a janitor at Hoover Dam and boatswain’s mate in the US Naval Reserve, and La Vina Elizabeth (née Haas) Downing, a Coloradoan of German descent. When Ted was an infant, the couple lived with Tommy’s grandparents in Boulder City, Nevada, where Tommy, a left-handed pitcher, organized the area’s first baseball team. Ted’s sister Karen was born in 1943.

In time, La Vina left Tommy. She and the children moved in with her parents in Betteravia, California, where she worked at a sugar factory. She remarried, to dairyman Lloyd Everett Davidson in 1948, and the family made their home on a cattle ranch in nearby Santa Maria. When Ted was nine, Tommy Downing was found dead of a suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning inside his coupe,3 seven months after leg and hip injuries from a bad car accident left the onetime all-state athlete disabled.4 Downing was 28, and left behind a note avowing his love for wife Jo Anne.5

Lloyd Davidson faithfully caught young Ted’s practice pitches in the driveway after long days spent working on the ranch. Ted pitched for the Union Sugar Babes beginning in 1950, the year Little League Baseball first came to Santa Maria, and helped lead the team to a league title. He crossed paths in 1951 with his future teammate in Cincinnati—ace hurler Jim Maloney, then an 11-year-old center fielder—when Davidson’s Santa Maria All-Stars fell in the regional playoffs to Maloney’s North Fresno nine.6 Davidson tossed three regular-season no-hitters in 1952; one was a perfect game on June 17, the first in Santa Maria’s Little League history.7

As a junior at Santa Maria Union High School in 1956, Davidson posted a 15-1 record with 159 strikeouts. Among his 15 wins were eight shutouts and six one-hitters, earning him the California Interscholastic Federation’s North-South Player of the Year honors. “As I remember, even in high school, Ted never got shook up—even if he got behind or bases loaded, no outs. It didn’t seem to bother him,” said John Ventura, a former left-handed pitcher and Davidson’s teammate on the school’s junior varsity and varsity teams.8

Davidson’s senior year was marred by a pattern of truancy,9 prompting the school’s dean of students—the Davidsons’ next-door neighbor—to pay the household a visit. “We’ve been trying to call you, and there’s no answer,” the school officer advised Ted’s parents.10 Suspicious, they unscrewed the bottom of the telephone to find that Ted had dampened the ring by stuffing cotton into the brass bells.11 He did not graduate,12 instead joining the semipro Santa Maria Indians, where he played from 1957 to 1959. Between seasons for the Indians, he briefly studied at Allan Hancock College and pitched for the school’s 5-12 Bulldogs in 1959.

Davidson inked his first professional contract, with the Cincinnati Reds, on May 6, 1960. He was signed by Bobby Mattick, a former Chicago Cubs and Reds infielder turned scout. “Bobby Mattick signed a lot of great players there for the Reds during that era; he was involved in Vada Pinson and Frank Robinson,” said Maloney, another of the scout’s notable signees.13 Davidson declined to play for Johnny Vander Meer’s Topeka Reds, instead choosing to join the lower Class-D Florida State League to gain experience.14

It was there that he first met Dave Bristol, the Palatka Redlegs’ fiery young skipper and second baseman. The 27-year-old Bristol swung a hot bat for Palatka, hitting .295 in 499 at-bats in 1960; only one of his players had a better average that season in as many tries. In one game Bristol went 4-for-5 “in between chewing out the umpires,” a sportswriter noted.15 He never played a day in the majors, but as a minor-league player-manager was an early influence in the careers of future Reds Tommy Helms, Mel Queen, and Davidson. “In Palatka we traveled in station wagons and [Davidson] rode in my car … he would help me drive and we talked baseball a lot,” Bristol said.16 Davidson posted a league-best 2.35 ERA that season over 24 games and amassed 124 strikeouts in 142 innings.

Throughout his five years in the minors, Davidson played in only three games for a manager other than Bristol, all with the Single-A Columbia Reds under Ted Beard in 1961. After a monthlong stay at Columbia, Davidson was transferred to Class-B Topeka, where Bristol was the new skipper and the lefty could start more regularly.17 Davidson’s highlights there included fanning 13 of Earl Weaver’s Fox Cities batters en route to his sixth victory, and shutting out the Cedar Rapids Braves without walking a batter for his season-high 13th win. But for all his starts—38 in his first two minor-league seasons—Davidson couldn’t help but think that with Cincinnati’s aging bullpen, converting to a reliever would punch his ticket to the majors.18

He followed Bristol through the Reds’ system to Macon and San Diego, where in 1964 the Triple-A Padres, five years before the major-league expansion team of the same name began play, won the Pacific Coast League championship by beating the home run–bashing Arkansas Travelers. Davidson entered the game in the fifth and was awarded the win. “Ted Wills was the starting pitcher, and I took him out and Ted [Davidson] finished the game,” Bristol recalled.19 A ninth-inning home run off Davidson by Arkansas’s Pat Corrales was trivial, and San Diego won 11–5.

When the Cincinnati Reds optioned Davidson to San Diego at the conclusion of spring training in 1965, he was ready to quit baseball.20 Then, in July, he received a 1:00 a.m. phone call telling him to pack and make a flight to Houston. “Ya mean I’ve been traded?” he asked.21 No, he was told—struggling left-hander Gerry Arrigo had been demoted, and Davidson would be joining the Reds for a four-game series with the Astros. He debuted on July 24 in the first game of a doubleheader, relieving Jim Duffalo with one out and the bases loaded in the sixth. Davidson induced the next batter, Houston rookie Joe Morgan, to hit into a 5-2-3 double play to end the inning. Davidson finished the game, allowing no hits and two walks and striking out four, but the Reds lost 4–2. He later said that it was one of the rare times he was nervous when pitching in the big leagues.22

On the road, Davidson absorbed the advice of roommate Roger Craig, the Reds’ 35-year-old veteran right-handed starter. In mid-August Reds manager Dick Sisler turned to an under-the-weather Davidson to start against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Sammy Ellis, a 22-game winner that season, had warned Davidson before the game to be especially careful pitching to Billy Williams, who had tagged Ellis for a two-run homer back in June. But Davidson would suffer a similar fate in the fifth inning, a solo home run to improve Williams’s hitting streak to 10 games. It was one of three runs and eight hits Davidson gave up across six innings, in what would be his only major-league start.

He picked up his third win of the season on August 26, allowing only one hit in six innings of relief in a notable game that marked the Reds’ last appearance in Milwaukee for almost 33 years.23 Eddie Mathews put Davidson among the “calmest, most poised rookies” he ever saw as an opposing batter.24 The third baseman was a 1-for-12 lifetime hitter off the left-hander.

The Philadelphia Phillies’ Dick Allen, however, hit Davidson exceptionally well, going 4-for-9 with three home runs off him in 1966. When a messenger knocked on the Reds’ clubhouse door on an offday that season at Connie Mack Stadium, closer Billy McCool teased, “That’s Richie Allen—he wants to know if Davidson will come out and pitch to him.”25 The next day, Davidson silenced the room by pitching a pair of clean innings and retiring Allen on a flyout to right.

The 1966 season was Davidson’s most active in the majors: he appeared in 54 games and logged 85 1/3 innings pitched. In a 14-game stretch that season between July 31 and August 31, Davidson allowed only one run in 23 innings and induced mostly groundouts with his sinker. His repertoire also included a curveball, a slider, and a knuckle changeup. Bristol remembered him having “not an outstanding fastball but good control.”26 Ventura recalled, “He didn’t throw that hard, but he was a lot like Fernando Valenzuela; he could throw the ball and spot it, and that’s what got him there.”27

Davidson’s career took a fateful turn outside a Tampa cocktail lounge on Thursday, March 9, 1967. The six-foot, 176-pounder threw a round of batting practice that day at Al Lopez Field, dazzling coach Mel Harder. “Davidson is really firing the ball this spring,” he remarked to Bristol, who had taken over as Cincinnati Reds manager the previous July.28 With McCool’s impending move to the rotation, Davidson stood to become the Reds bullpen’s premier left-hander. He could finally smell the roses at spring training without the threat of a cut hanging over him.

About 10 miles from the Reds’ Tampa hotel lived Davidson’s wife of four years, 24-year-old Texas native Mary Ruth Sharp-Davidson, and their two preschool-aged daughters. Mary hadn’t seen Ted since a 1966 series in Atlanta. Theirs was a complicated, on-again, off-again relationship. They met at spring training and wedded on November 12, 1962, but by the time Davidson was called up to Cincinnati in 1965, divorce proceedings were already underway, and Mary and the children stayed behind in Florida. The couple reconciled and moved to Santa Maria and their divorce case was dismissed,29 but the marriage again crumbled. A self-described alcoholic, Mary worked as a bartender during the couple’s rocky patches.30 She had been hospitalized for two weeks in January 1967 for a nervous breakdown.31

Spring training was a chance for Davidson to see the children, but according to Mary’s account of the events of March 9, he was a no-show at the hotel that afternoon.32 Around 6:45, Davidson went to the Park Lane Lounge, a haunt where he was friendly with a 33-year-old waitress whose shift was about to end.33 She and Davidson had dinner plans. Mary knew about the woman, and after phoning the bar to verify that Davidson was there, showed up a short time later, making a scene and accusing him of infidelity.34 Embarrassed, he ducked out a back door.

Mary left through the front entrance, and in an alley behind the bar, produced a Colt .22-caliber automatic pistol—the very gun that Davidson had bought for her protection. “Ted had bought her that gun for when he was on the road in San Diego … she was by herself a lot,” said Davidson’s sister, Karen Strickland.35 Mary fired the gun at her husband from approximately six to eight feet away, leaving a pair of bullet holes encircled with powder burns in his green V-neck sweater. He lost consciousness and fell to the pavement. Passersby discovered him after Mary had driven off in a white Corvair.

She traveled about two miles east toward the bay and called police from the Carousel Lounge, another Tampa bar. There, she was arrested—“half-carried in near-hysterics to the wagon,” reported the Tampa Times.36 Mary was freed after posting a $2,500 bond, an amount police said was commensurate to the charge of assault to murder.

Davidson was rushed by ambulance to Tampa General Hospital with wounds to his left waist and right chest that required surgery. Because Davidson was shot near his nonthrowing shoulder, his surgeon was optimistic about a quicker return to baseball, but not before Bristol was forced to rework his roster of pitchers. Semiretired left-hander Joe Nuxhall offered to stay on when he learned that Davidson was injured, but formally retired when told he would only be traded.37 “I remember Dave Bristol telling us that [Davidson] was going to be their number one reliefer that year,” Strickland said.38 “She got what she wanted, I guess.”

Bristol and Reds third-base coach Jimmy Bragan visited Davidson soon after he was moved out of intensive care. A scrappy Georgian who kept a chaw of tobacco in his cheek, Bristol came from a rough-and-tumble minor-league era. He was once at the center of a bloody fistfight in Macon, worked over by a handful of opposing players while on the ground tussling with Charlotte manager Red Robbins. Bristol’s eye was blackened, his cheek bruised, and his face left with impressions from the Charlotte catcher’s mask. The story goes that Bristol, lying on the dirt at third base, gazed up at the 6-foot-2 backstop and said, “Have you had enough or do you want some more?”39

The deep crow’s feet that branched from the corners of Bristol’s eyes hinted of a certain resilience, but the Reds manager was uncharacteristically squeamish at the sight of blood. As a high school football player, he was known to faint when given his tetanus shots.40 He once conked out when told of a murder that had been in the news.41 And in Room 324 at Tampa General Hospital, Bristol again swooned when visiting Davidson. “He wanted to show me where he got shot,” Bristol recalled.42 “There was another bed in the room with him, and I passed out and they put me on the bed. I didn’t want to see that … they were giving me ammonia and everything to try to bring me back to.”

When discharged from the hospital on March 23, 1967, Davidson returned home to Santa Maria to recuperate. Compounding his problems was an old knee injury, reaggravated when he crumpled to the ground in the shooting. “I remember sitting down with him, and he was supposed to go back to Tampa, Florida, for [Mary’s court hearing], and he decided not to,” said Ventura.43 After Davidson’s second no-show on April 25—he had flown to Cincinnati on the 23rd for treatment of his injured knee—the charge against Mary was dropped. Davidson was given a two-year window to return to Tampa to seek prosecution, but he never saw her again.44

By May he joined the Reds’ Triple-A team in Buffalo for a rehab stint, and on June 12 was activated by the Bisons. He pitched in 26 games there and was charged with 12 earned runs in 30 innings before rejoining the Reds on September 5. Davidson made his season debut the following night in Philadelphia, giving up four hits and three runs in 2 1/3 innings. Something about the left-hander was different. “He just didn’t have it,” Strickland recalled.45 Like Eddie Waitkus, the Phillies first baseman who was shot by an infatuated admirer in 1949, paranoia had crept into Davidson. “He had a fear of getting on the mound and not being able to see who was out in the [stands]—if somebody could be out there that could potentially shoot again,” said Davidson’s elder daughter, Lisa Crouse.46

Bristol had stuck to his plan, using McCool mostly as a starter in the first half. Veteran Ted Abernathy, a submarining right-hander whose low release point once caused the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Ron Fairly to complain that the ball blended in against the white rosin bag, shouldered the short relief load. “Abernathy came in and [Fairly] told the umpire—he called time-out—to move the rosin bag over to the other side of the mound,” Maloney recalled.47 Abernathy led the majors with 28 saves across a National League–most 70 appearances in 1967 and won The Sporting News’s distinction as top NL fireman.

Davidson began the 1968 season with a 9.45 ERA in the month of April. He was but a footnote in the Reds’ six-player deal with Atlanta on June 11, sidelined at the time with a sore shoulder he thought was caused by exposure to cold air conditioning.48 In his first game wearing a Braves uniform, he intentionally walked Curt Flood to load the bases in St. Louis and then gave up back-to-back singles to Tim McCarver and Orlando Cepeda that plated three runs on two pitches. In his four appearances for the Braves, Davidson posted a 6.75 ERA over 6 2/3 innings before being optioned to Richmond.

There, he went 1-5 and was demoted to Single-A Greenwood. In December 1968, the Cleveland Indians’ Double-A affiliate at Waterbury, Connecticut, selected Davidson in the Rule 5 Draft. Underweight and fatigued since the shooting, he had considered retiring before Cleveland drafted him. “Heck,” Davidson told the Plain Dealer, “there were occasions when I’d be sitting in the bullpen and I’d have to fight to stay awake at 9 o’clock.”49

He was promoted to the Indians’ Triple-A affiliate, the Portland Beavers, but missed part of Cleveland’s spring training exercises with a broken big toe. After joining Cleveland’s farm system, Davidson showed a tinge of black humor about the shooting by saying with a laugh, “I remembered the Indians trained in Arizona. I wasn’t about to go back to Florida.”50

After pitching in a smattering of games as a non-roster invitee, Davidson was cut on March 30 following back-to-back clunkers. His playing career concluded by passing through three organizations with short stints at Tacoma, Portland, and Tucson.

Across parts of four major-league seasons, Davidson compiled an 11-7 record with a 3.69 ERA and five saves. He was a shadow of his former self on the mound after being shot, unlike Malamud’s fictional Hobbs, who went on to flourish offensively as a converted outfielder in The Natural. By contrast, as a right-handed batter Davidson went hitless in 31 attempts. That’s not to say he couldn’t hit; in 1962, he stroked a clutch single down the right-field line in the bottom of the 10th inning to drive in the winning run for the Single-A Macon Peaches. But he reached base in the majors only once, on a walk by Houston’s Mike Cuellar in 1968 when Davidson played for Atlanta. As of 2025, he was one of only seven pitchers in major-league history without a hit in 30 or more lifetime at-bats, a list that included Armando Galarraga, Tony McKnight, Bo McLaughlin, Daryl Patterson, Charley Stanceu, and Randy Tate.

In his mid-30s, Davidson was brought back to the Santa Maria Indians to pitch an inning at a handful of home openers as a special attraction. He married New Yorker Joanne Elliott Dorso in 1968; the couple had a son before divorcing in September 1974. By then, Mary Davidson’s mother and stepfather had legal guardianship of Ted’s two daughters and had kept them insulated from news about the shooting. “We were pretty shielded from all that as children,” Crouse said.51 “My dad flew my sister and me out for Christmas one year; we were probably 10 and 11. And we found out from our cousins—my dad’s sister’s two boys—that my mother had shot my dad.”

Ted married his third wife, the former Joan Frances Sargent, in May 1975. He underwent quadruple heart bypass surgery in January 1983, at age 43. After that, he spent a couple of seasons as the semipro Indians’ pitching coach, instructing the likes of Tim Layana, who broke into the majors in 1990 and played parts of three seasons with the Reds and Giants. Davidson later operated a silkscreen business and worked as a truck dispatcher.

Mary became a tailor and opened an alterations shop in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1989. At the mention of the shooting in an interview with local Times columnist Jack Sanders the following year, Sanders couldn’t tell whether her face showed a sense of regret or satisfaction.52 Mary died of cancer53 on February 18, 1996, at age 53.

Ted and Joan retired in 2002 to Bullhead City, Arizona, a town bordering Nevada that is a mecca for casino-goers because of its proximity to Laughlin. Ted’s next four years were spent fishing and visiting casinos, and were described in his obituary as the best years of his life.54

Ted Davidson died on September 1, 2006, at age 66. While barbecuing over his outdoor pit, he took a respite inside his cooled garage from the 110-degree desert heat when he fell backward in his chair from a massive heart attack. Davidson, who had smoked much of his life, was deceased by the time medics arrived. His body was cremated and the ashes spread in the Sierra Nevada Mountains.55

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Ted Davidson’s daughter Lisa Crouse and sister Karen Strickland, Dave Bristol, Jim Maloney, and John Ventura for their memories. Thanks also to Linda Barrett of the Fort Worth Public Library, Joanne Britton-Holland of the City of Santa Maria Public Library, editor Rory Costello for making this story shine, Darryl Eisner, the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Research Center, the City of Tampa’s public records division, and the Topeka Room at the Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library.

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Photo credit: Ted Davidson, Trading Card Database.

Sources

The author relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and StatMuse.com for statistics and the Sporting News Baseball Player Contract Cards Collection for dates of transfers between teams. All other sources are shown in the Notes.

Notes

1 Si Burick, “Davidson Hit Twice: ‘My Name Is Mary … I’ve Shot a Man,” Dayton Daily News, March 10, 1967: 26.

2 “After I was shot by my former wife, I was never the same,” Davidson told Furman Bisher in “Players from A to Z: Where Are They Now?” Atlanta Journal, June 17, 1987: 10D.

3 Thomas Clifton Downing death certificate, file no. 49-311, Nevada State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, March 17, 1949; accessed using Ancestry.com.

4 “Downing Rites Held in Boulder,” Reno Evening Gazette, March 21, 1949: 5.

5 “Thomas Downing Found Dead in Gas Filled Car,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, March 16, 1949: 12.

6 Later, as Davidson’s teammate in Cincinnati, Maloney had a small-world moment when reminded that their paths had intersected in Little League.

7 “Little Leaguers Run Wild, 20–0,” Santa Maria Times, August 7, 1952: 2; also, “Davidson Tosses History-Making Perfect Contest,” Santa Maria Times, June 18, 1952: 2.

8 Ventura, interview with author, August 13, 2025. Ventura’s years-long friendship with Davidson and his mother went back to Little League, where Ventura pitched for the rival Associated Drug Dodgers. Of Ventura’s four boys three played baseball, including Robin Ventura, who played 16 years in the majors—mostly as an infielder for the Chicago White Sox, a team he later managed for five seasons.

9 Karen Strickland, interview with author, September 4, 2025; also, Ventura interview.

10 Strickland interview.

11 Strickland interview.

12 Santa Maria High School’s records showed no graduation stamp on Davidson’s transcript. In 2024, he was inducted into the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame.

13 Maloney, interview with author, August 23, 2025. “I had about 25 innings of pitching when I signed [with the Reds],” he said. “Half the teams wanted me as an infielder because I could hit a little bit, and half of them wanted me as a pitcher because I had a strong arm [as a] shortstop.” Maloney went on to average 16 wins and 196 strikeouts per season as the Reds’ ace over a seven-year stretch between 1963 and 1969, while maintaining a 2.90 ERA.

14 “Davidson Pens Cincy Contract,” Santa Maria Times, May 7, 1960: 7.

15 Jack Ellison, “Saints Win 7–6 to End 7-Game Losing Streak,” St. Petersburg Times, May 17, 1960: 2C.

16 Bristol, interview with author, August 28, 2025.

17 “Muddy Field Stops Topeka,” Topeka Daily Capital, May 19, 1961: 13.

18 Jim Ferguson, “Hard Work, Perseverance Put Teddy off Relief,” Dayton Daily News, August 17, 1965: 9.

19 Bristol interview.

20 “Coast Clippings,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1965: 42.

21 Chan Keith, “The Inside Pitch,” Santa Maria Times, November 15, 1965: 7.

22 Si Burick, “Si-ings: Ted Davidson Still Believes—So Do Those in Authority, Now,” Dayton Daily News, March 3, 1966: 20.

23 The Braves moved to Atlanta the next season, and the expansion-era Milwaukee Brewers were an American League team until 1998.

24 Chan Keith, “The Inside Pitch,” Santa Maria Times, November 16, 1965: 9.

25 Jim Ferguson, “Relaxed Reds Resume First Division Battle,” Dayton Daily News, September 9, 1966: 21.

26 Bristol interview.

27 Ventura interview.

28 Lou Smith, “Who’ll Replace Davidson?” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 11, 1967: 12.

29 Records of the Hillsborough County, Florida, Clerk of Circuit Court’s office, archive department, email message to author, August 15, 2025.

30 Jacquin Sanders, “She Altered a Life of Liquor and Losers,” St. Petersburg Times, August 21, 1990: 1B.

31 Eleanor Jordan, “Wounded Pitcher Calm, Talkative at Hospital,” Tampa Tribune, March 11, 1967: 1B.

32 John Dye, “Ballplayer’s Wife ‘Numb, Scared,’” Tampa Times, March 10, 1967: 6.

33 Tampa Police Department detective’s interview with Alice E. Faltus, March 10, 1967, case no. 7-6297, supplement to offense report. Faltus stated that Davidson had told her he was divorced.

34 Faltus police interview. “Mary told me that Ted had been seeing another woman and she had caught them,” Mary’s attorney Bob Anderson Mitcham wrote in his memoir Justice from Buttermilk Bottom (n.p.: International Legal Press, 2005), 59.

35 Strickland interview.

36 “Wounded Pitcher Will Hurl Again,” Tampa Times, March 10, 1967: 1, 6.

37 John Kiesewetter, “The Old Left-Hander,” Tristate: The Cincinnati Enquirer Magazine, July 13, 1986: 6.

38 Strickland interview.

39 Glenn Schwarz, “Pugilism Nothing New to Bristol,” San Francisco Examiner, June 20, 1980: F3.

40 Bristol interview.

41 Allen Garvin, “What in the World!” Family Weekly, March 12, 1967: 2.

42 Bristol interview.

43 Ventura interview.

44 Strickland interview.

45 Strickland interview.

46 Crouse, interview with author, September 3, 2025.

47 Maloney interview.

48 Earl Lawson, “Reds’ Bullpen in Big Trouble,” Cincinnati Post & Times-Star, June 11, 1968: 19.

49 Russell Schneider, “Davidson Looks Ahead Now—to Indians Job,” Plain Dealer, March 16, 1969: 2C.

50 Schneider, “Davidson Looks Ahead Now—to Indians Job.”

51 Crouse interview.

52 Sanders, “She Altered a Life of Liquor and Losers.”

53 Crouse interview.

54 Thomas Eugene “Ted” Davidson, “Obituaries,” Santa Maria Times, September 10, 2006: 13.

55 Strickland, in discussion with the author, October 16, 2025.

Full Name

Thomas Eugene Davidson

Born

October 4, 1939 at Las Vegas, NV (USA)

Died

September 1, 2006 at Bullhead City, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.