Orlando Cepeda

When Orlando Cepeda stood on the podium in Cooperstown, New York, on July 25, 1999, it is likely that no man had followed a more difficult path to the Baseball Hall of Fame, or that any man was any happier to attain the honor. Cepeda had escaped the slums of Puerto Rico to attain stardom at a very young age, and he overcame numerous injuries during his career, and even worse personal difficulties after leaving baseball. Although he had two remarkable comeback seasons in his baseball career, he had his biggest and most impressive comeback years later, when after a decade of humiliation he again stood on a ball field and listened to the roar of a crowd.

When Orlando Cepeda stood on the podium in Cooperstown, New York, on July 25, 1999, it is likely that no man had followed a more difficult path to the Baseball Hall of Fame, or that any man was any happier to attain the honor. Cepeda had escaped the slums of Puerto Rico to attain stardom at a very young age, and he overcame numerous injuries during his career, and even worse personal difficulties after leaving baseball. Although he had two remarkable comeback seasons in his baseball career, he had his biggest and most impressive comeback years later, when after a decade of humiliation he again stood on a ball field and listened to the roar of a crowd.

To know Orlando, one must first know his father. Pedro “Perucho” Anibal Cepeda, born in 1906, was one of the greatest ballplayers the island of Puerto Rico ever produced, starring in leagues in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico from the mid-1920s until 1950, when he was 45. He came up as a shortstop, and his strong hitting (he won numerous batting titles) and aggressive baserunning earned him the nickname “The Babe Cobb of Puerto Rico.”1 Perucho resisted many overtures to play in the Negro Leagues because he did not want to endure the segregated culture of the United States. So he stayed home, earning no more than $60 a week as a ballplayer and a bit more working for the San Juan Water Department.

Orlando Manuel Cepeda Pennes was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, on September 17, 1937, to Carmen Pennes, a tiny (4-feet-11), beautiful woman, and Perucho Cepeda. (Per the custom in many Latino countries, each parent contributed half of his double surname, with the father’s half being used in everyday life.) Orlando Cepeda was preceded by Pedro, born four years earlier, and he also had sisters born to his father’s girlfriends, sisters whom Cepeda grew close to. Although surrounded by love, Cepeda grew up in stifling poverty — his father made little money, and often gambled what he made — and by crime and drugs, habits Orlando participated in. “What saved me,” he later wrote, “was baseball — and the talent I inherited from my father. Had it not been for baseball and the legacy of Perucho Cepeda, I could have followed my boyhood pals into a world of crime, violence, and hate.”2

His family moved a few times before settling in Santurce, a district of San Juan. The son of a baseball star, Cepeda had a childhood dominated by the game, including visits from famous ballplayers — like Satchel Paige, his father’s friend. Orlando played a lot of baseball, but suffered the first of his many knee injuries playing basketball when he was 15. During his long recovery, he grew six inches and added more than 40 pounds to his previously scrawny frame. “Before I was in the hospital we had a short wall. I couldn’t hit over it. But afterward, whoosh!”3 He soon grew to 6-feet-1 and 210 pounds, and was playing mainly first base.

In late 1953 the 16-year-old was scouted by Pete Zorilla, who ran the Santurce Crabbers in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Zorilla asked his friend Perucho if Orlando could serve as the Crabbers’ batboy and work out with the club. The next winter, Zorilla arranged for the young Cepeda and a few other islanders (including future big-league teammate José Pagán) to go to a New York Giants tryout camp in Melbourne, Florida. Because they were all underage, and had never left the island, they were accompanied by the 20-year-old Roberto Clemente, on his way to spring training with the Pirates. Cepeda impressed at the camp, and signed a contract that included a $500 bonus.

Just days before Orlando’s first professional game, with the Salem Rebels of the Appalachian League, the 49-year-old Perucho died after a long bout with malaria. Cepeda returned home and used his bonus money for the funeral. He returned to Virginia but struggled on and off the field. “I lived in the black part of town, and on Sunday mornings I’d hear the people singing gospel music in the church across the street. I’d sit by the window in my room listening, and I’d cry from misery and loneliness.”4

After a month with Salem, where he hit just .247 with one homer, he was released but picked up by the Giants’ Kokomo, Indiana, club. The 17-year-old starred there, batting .393 with 21 home runs in just 92 games. The next year, in St. Cloud, Minnesota, all Cepeda did was win the Northern League Triple Crown, with 26 home runs, 112 RBIs, and a .355 batting average. In 1957 he made it all the way to Minneapolis, the Giants’ Triple-A affiliate in the American Association. It was at that spring that he first met Felipe Alou, a Dominican outfielder who became a lifelong friend. Alou was demoted to the Eastern League, but Cepeda became the club’s first baseman and had another fine season: 25 home runs, 108 RBIs, .309 average. “If he ever learns the strike zone,” said Red Davis, his manager, “he’ll be murder up there. He’s tough enough now.”5 Cepeda drew just 27 walks, and he would always be known as a free swinger.

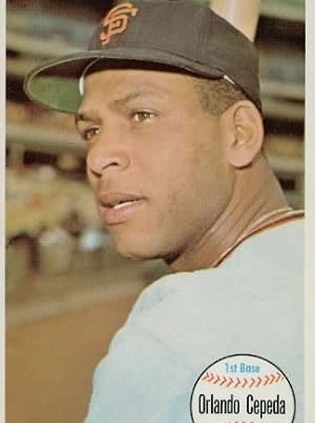

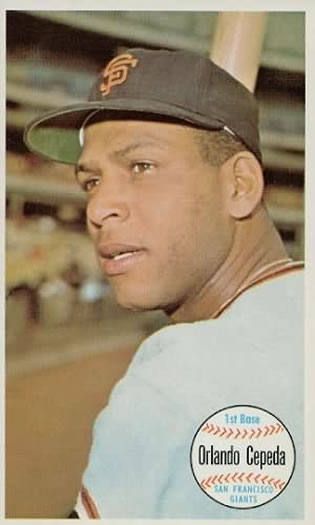

In 1958 the Giants moved from New York to San Francisco. After winning the World Series in 1954, the club had slid to sixth place in both 1956 and 1957. But help was on the way. When Cepeda arrived at spring training in 1958, he was joined by fellow prospects Felipe Alou, Leon Wagner, Willie Kirkland, Willie McCovey, Jim Davenport, and José Pagán. The Giants had an opening at first base because Bill White was serving a two-year stint in the Army. Whitey Lockman had held the position in 1957, but manager Bill Rigney asked him to work with the 20-year-old Cepeda that March. The youngster had a tremendous spring, crushing home runs, fielding his position well, and running the bases. “Hey, Rig,” said Lockman one day to Rigney. “This kid Cepeda is three years away.” Rigney was startled, until Lockman added, “from the Hall of Fame.”6

On April 15, 1958, the Giants hosted the Los Angeles Dodgers at Seals Stadium, in the first major-league game ever played in California. Cepeda played first base and batted fifth, joining right fielder Kirkland and third baseman Davenport, also playing their first big-league games. The Giants prevailed, 8-0, behind Rubén Gómez, with Cepeda hitting his first home run, off Don Bessent. This was the start of a magical season for the 20-year-old, as he hit .312 with 25 home runs and a league-leading 38 doubles. After the season he was the unanimous winner of the NL Rookie of the Year award.

Cepeda and San Francisco were a perfect fit. While Willie Mays had starred in New York before the Giants moved west, the provincial San Franciscans considered Cepeda to be one of theirs. And the feeling was mutual. “Right from the beginning, I fell in love with the city,” Cepeda said. “There was everything that I liked. We played more day games then, so I usually had at least two nights a week free. On Thursdays, I would always go to the Copacabana to hear the Latin music. On Sundays, after games, I’d go to the Jazz Workshop for the jam sessions. At the Blackhawk, I’d hear Miles Davis, John Coltrane. … I roomed then with Felipe Alou and Rubén Gómez, but I was the only one who liked to go out at night. Felipe was very religious and quiet, and Ruben just liked to play golf, so he wasn’t a night person. But I was single, and I just loved that town.”7

Cepeda’s stardom, which he sustained, was considerably complicated in 1959 by the arrival of Willie McCovey, another young hitting phenom who, like Cepeda, played first base. Though Cepeda had another great year in 1959 (27 homers, .317), McCovey’s extraordinary four months in Phoenix (29 homers, .372) forced the Giants’ hand. When McCovey debuted on July 30 (hitting two singles and two triples), Cepeda played third base. After four games there, manager Bill Rigney moved Cepeda to left field, which he played for the rest of the season.

The Giants spent most of the next five years dealing with the problem of having two All-Star first basemen. Though McCovey had a great two months in 1959, he was plagued by inconsistency and struggles against left-handed pitchers for a few years. Cepeda, regardless of his position, kept playing and kept hitting. But his reluctance to play the outfield became a matter of controversy. “I just wasn’t ready mentally,” Cepeda said years later. “I know I could’ve played left field if I’d put my mind to it, but I was only 21 years old and very sensitive. Friends and other players kept telling me I should demand to play first. It was all pride with me. And ignorance.”8

“I could understand his reluctance,” Rigney recalled. “But Cepeda was the better athlete, so I thought he could make the move to another position more easily. But he would come up to me and say, ‘Bill, I’m the first baseman not the left fielder.’ What could you do? He was the most popular San Francisco Giant. It was very hard not to like Orlando Cepeda. But this became an unresolvable situation.”9 McCovey was back in the minor leagues briefly in 1960, which got Cepeda his first-base job back, and the two shuttled between the outfield and first base in 1961. In 1962 manager Al Dark moved McCovey to left field and Cepeda was back at first base. Cepeda kept hitting, but McCovey did not become a consistent star as long as he and Cepeda remained teammates.

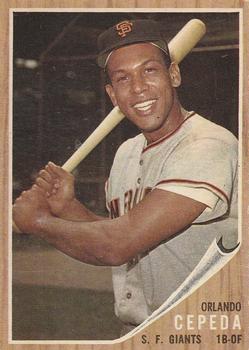

Most of Cepeda’s offensive seasons look alike, but his 1961 stands out as a singularly great year; he led the league with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs while hitting .311. Baseball held two All-Star games each season from 1959 to 1962, and Cepeda was named to the team all eight times, starting in five of them. In his career he was named to 11 All-Star teams, playing in nine of them but hitting just 1-for-27. Although he continued to play, Cepeda hurt his right knee in a home-plate collision in 1961 and never had another day without pain.

After a few years of criticism for their underachieving, the Giants broke through in 1962 to win their first pennant in San Francisco. After tying the Dodgers at 101-61 through the regular schedule, they prevailed in a best-of-three pennant playoff, before falling to the New York Yankees in seven games in the World Series. Cepeda had another excellent season, batting .306 with 35 homers and 114 RBIs. The season was not without its problems — he was fined by Dark in August for not hustling, then hit just .231 with three homers after August. In the regular season final, Dark benched him, though Cepeda had four hits the day before in a doubleheader. He played in all three playoff games (3-for-13 with a home run) and hit just 3-for-19 in the World Series.

After a few years of criticism for their underachieving, the Giants broke through in 1962 to win their first pennant in San Francisco. After tying the Dodgers at 101-61 through the regular schedule, they prevailed in a best-of-three pennant playoff, before falling to the New York Yankees in seven games in the World Series. Cepeda had another excellent season, batting .306 with 35 homers and 114 RBIs. The season was not without its problems — he was fined by Dark in August for not hustling, then hit just .231 with three homers after August. In the regular season final, Dark benched him, though Cepeda had four hits the day before in a doubleheader. He played in all three playoff games (3-for-13 with a home run) and hit just 3-for-19 in the World Series.

Cepeda’s final years in San Francisco were clouded by his terrible relationship with Dark. Cepeda believed that Dark did not like blacks or, especially, Latinos. Dark did not approve of the Giants’ many Latino players speaking Spanish, and he believed their loud Latino music and laughter to be indicative of not taking the game seriously.10 Moreover, Dark developed his own plus-minus rating system, in which he gave people positive or negative points for what they did on the field. While Mays, unsurprisingly, led the 1962 team with over 100 points, Cepeda came in at negative 40. “There are,” said Dark, “winning .275 hitters and losing .310 hitters.”11 That Dark kept such a system and publicly used it to denigrate one of his players is astonishing.

In the remaining two years of his stewardship of the Giants, Dark had run-ins with Cepeda numerous times for what the manager believed was a lack of hustle and what Cepeda claimed was a hurt knee. “The knee hurt me all the time,” said Cepeda, “and I always aggravate it when I slide or stretch or even hit. Some people think that because we are Latins — because we did not have everything growing up — we are not supposed to get hurt. But my knee was hurt. Dark thought I was trying not to play. He treated me like a child. I am a human being, whether I am blue or black or white or green. We Latins are different, but we are still human beings. Dark did not respect our differences.”12

Through it all, Cepeda continued to hit. He batted .316 with 34 home runs in 1963, then .304 and 31 in 1964. Through the first seven years of his career, he had hit .309, with a .353 on-base percentage and .537 slugging percentage. His 222 home runs were three more than Henry Aaron had through his first seven seasons. At the end of the 1964 season, Cepeda was still just 27 years old.

His return to first base full-time in 1962 surely helped his knee, but when he reported to spring training in 1965 he could barely put any weight on it. New manager Herman Franks, like Dark, felt that Cepeda was dogging it, so Cepeda tried to tough it out. After hobbling through the spring, Cepeda was used mainly as a pinch-hitter for the first month of the season (three singles in ten at-bats) before finally going on the disabled list in May. He returned as a pinch-hitter in August, but finished just .176 in 34 at-bats for the year. After the season he had surgery on his right knee.

When he returned in the spring of 1966, McCovey was finally fully entrenched at first base. Playing mostly left field, Cepeda started slowly but was hitting .286 with three homers in 19 games on May 8. On that date, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Ray Sadecki. Though Cepeda was shocked and upset by the trade, he was joining a team that had a gaping hole at first base, the only position he wanted to play. In fact, Cepeda never played the outfield again. Batting cleanup for the rest of the year, he homered in his first game and finished the season hitting .301 with 20 home runs in 123 games.

After years of discomfort in San Francisco, Cepeda was beloved by his teammates and manager Red Schoendienst. He became a jokester in the clubhouse, and his taste for jazz and Latin music earned him the nickname Cha Cha. Cepeda noted the change. “You know,” he said, “if I do all this in San Francisco they would give me a funny look all the time and everyone would think there is something wrong with me.”13 In 1967 he completed his comeback in style, hitting .325 with 25 home runs and a league-leading 111 runs batted in. After two straight losing seasons, the Cardinals rolled to the NL pennant and victory over the Red Sox in the World Series. After the season Cepeda was unanimously named the league’s Most Valuable Player.

After his MVP season in 1967, the 30-year-old Cepeda followed up with the worst full season of his career, batting just .248 with 16 home runs. The 1968 Cardinals returned to the World Series, this time losing to the Detroit Tigers in seven games. After hitting poorly in the Series in both 1962 and 1967, this time Cepeda hit .250 and slugged two home runs.

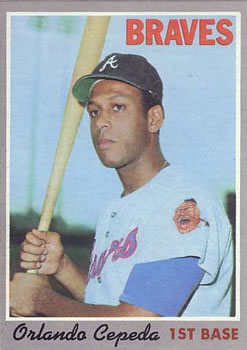

Cepeda returned to spring training in 1969 hoping for a comeback year with the Cardinals. But on March 17, he received the unwelcome news that he had been traded to the Atlanta Braves for star catcher-first baseman Joe Torre. Cepeda loved St. Louis and his teammates, and he was uncomfortable with the idea of playing in the South. In the end, he enjoyed his time in Atlanta, which reunited him with his good friend Felipe Alou and allowed him to play with the great Henry Aaron.

Cepeda returned to spring training in 1969 hoping for a comeback year with the Cardinals. But on March 17, he received the unwelcome news that he had been traded to the Atlanta Braves for star catcher-first baseman Joe Torre. Cepeda loved St. Louis and his teammates, and he was uncomfortable with the idea of playing in the South. In the end, he enjoyed his time in Atlanta, which reunited him with his good friend Felipe Alou and allowed him to play with the great Henry Aaron.

His first year in Atlanta was a struggle personally and professionally (.257 with 22 home runs) but a big success for the team, which finished first in the NL West in the first year of divisional play. Cepeda hit .455 in the playoff series against the Mets, with a home run off Nolan Ryan in Game Three, but the Mets swept the three-game series. Cepeda came back with a vengeance in 1970 (.305, 34 home runs, 111 RBIs), though the Braves dropped to fifth place.

Cepeda started 1971 as good as ever — on June 1 he was slugging .584 with 13 home runs, among the league leaders in both categories. Later that month, in the act of getting up to answer the telephone at home, his left knee — up until then, his “good” knee — collapsed. The Braves doctor told him the knee was “finished.”14 He hobbled out to first base for a few weeks before finally shutting it down in late July. He underwent another knee surgery in September and went home to Puerto Rico.

A hobbled Cepeda showed up in the spring wanting to play. He played only twice in April, hit .350 (but with little power) playing half-time in May, and hit just .182 in June. On June 29 he was traded to the Oakland A’s for pitcher Denny McLain, another recent MVP who looked to be nearing the end of the line. He pinch-hit three times for Oakland, before shutting it down. After the season he was released. With two bad knees, Cepeda’s career looked to be finished.

On January 11, 1973, the American League agreed to a three-year trial run of the designated-hitter rule, allowing a batter to hit in place of the pitcher throughout the game. Along with its strategic consequences, there was suddenly a place in the game for good hitters who could not play the field. A week later the Red Sox signed Cepeda with this role in mind. For the 1973 season, Cepeda played 142 games, never once playing in the field. He hit .289 with 20 home runs and 86 RBIs and was the first recipient of the Designated Hitter of the Year award (later named the Edgar Martinez Award).

Just before the 1974 season, new manager Darrell Johnson decided he wanted to make room for younger players, and he released Cepeda and veteran shortstop Luis Aparicio, surprising most observers. Cepeda was crushed and remarkably was unable to find another job. He played briefly in Mexico before finally being signed by the Kansas City Royals in August. He hit just .215 in 107 at-bats before drawing another release. This time he was finally through after 17 seasons and 379 home runs.

Cepeda had married Annie early in his career and fathered Orlando Jr., but after years of his infidelity, and at least one child with another woman, they divorced in 1973. He married Nydia in 1975, but his behavior did not improve. In December 1975 he was arrested for taking delivery of 170 pounds of marijuana. Although he admitted to being a marijuana user, he claimed that he was expecting only a small amount for himself, and that he was not a dealer. Puerto Rico had made Cepeda a hero after the tragic death of Roberto Clemente three years earlier, but his arrest made him a pariah on the island. He and his family received death threats. He lost all of his money on his legal case, which caused him to miss child-support payments and led to more legal trouble. He finally stood trial in 1978, was found guilty, and was sentenced to five years in prison. He served ten months in a minimum-security facility in Florida.

Upon his release Cepeda continued to struggle. Still shunned at home, he had trouble finding and keeping work. He got a job as a minor-league hitting coach for the White Sox but failed to show up a few times and was let go. In 1984 he, Nydia and their two children moved to Los Angeles so he could conduct baseball clinics, but after a few months of fighting, his family moved back home, leaving Orlando with Orlando Jr., who had joined him in LA.

Orlando credited his embrace of Buddhism in the 1980s for turning his life around. It allowed him to take responsibility for the mess he had made of his life, to get control of his shame and his anger, and to help him find a path forward. He also met Mirian Ortiz, a Puerto Rican woman who eventually became his third wife. He and Mirian moved to the Bay Area, close to where his baseball journey had begun 30 years earlier. In 1987 he took part in a Giants Fantasy Camp in Arizona. “Of all the ex-players we had there,” recalled a team official, “Orlando was the approachable idol. I couldn’t believe it; I kept waiting for the flaws to show in that great personality. But there were no flaws. He is such a genuine person, such an emotional person, that you feel like hugging him. You get this sense that people just want to love him. I asked him if he’d be interested in coming back to work for the Giants.”15

The next year Cepeda started by making trips for the team to scout or help with instruction. In the 1989 NLCS, he was asked to throw out the first ball before the third game, listening from the pitcher’s mound as the cheers rained down on him. For more than 25 years Cepeda acted as a humanitarian ambassador for the club, showing up wherever and whenever they wanted him to, including inner-city schools throughout the country. He also made appearances in Puerto Rico, his native island that once again embraced him.

In 1999 Cepeda was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, 25 years after his last at-bat. “I wasn’t ready to get in before,” he said. “I still had work to do in healing myself.”16 That same year the Giants retired his number 30. In September 2008 the Giants unveiled a statue of Cepeda outside the 2nd Street entrance of AT&T Park. “When things like this happen to you, that’s when I say to myself, ‘Orlando, you’re a very lucky person,’” Cepeda said after seeing his bronze likeness, holding a ball and first baseman’s mitt.17

As of 2014, Cepeda lived in Fairfield, 35 miles northeast of San Francisco, with Mirian, and still worked for the Giants. He had five sons, Orlando Jr., Malcolm, Ali, and Karl and Jason.

Postscript

Cepeda died at the age of 86 on June 28, 2024.

Notes

1 Orlando Cepeda and Herb Fagen, Baby Bull: From Hardball to Hard Time and Back (Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 1998), 2.

2 Cepeda and Fagen, 7.

3 Robert Creamer, “Giants — A Smash Hit in San Francisco,” Sports Illustrated, June 16, 1958.

4 Ron Fimrite, “The Heart of a Giant,” Sports Illustrated, October 16, 1991.

5 Cepeda and Fagen, 31.

6 Roy Terrell, “The Sa-fra-seeko Kid,” Sports Illustrated, May 23 1960.

7 Fimrite, “The Heart of a Giant.”

8 Fimrite, “The Heart of a Giant.”

9 Fimrite, “The Heart of a Giant.”

10 Peter Bjarkman, Baseball With a Latin Beat — A History of the Latin American Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1994), 138.

11 Richard Boyle, “Time of Trial for Alvin Dark,” Sports Illustrated, July 06, 1964

12 Mark Mulvoy, “Cha Cha Goes Boom, Boom, Boom!” Sports Illustrated, July 24, 1967.

13 Mulvoy, “Cha Cha Goes Boom, Boom, Boom!”

14 Cepeda and Fagen, 161.

15 Fimrite, “The Heart of a Giant.”

16 William Nack, “From Shame to Frame,” Sports Illustrated, July 26, 1999.

17 John Shea, “Cepeda Honored With His Own Statue at the Ballpark,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 7, 2008.

Full Name

Orlando Manuel Cepeda Pennes

Born

September 17, 28, 1937 at Ponce, (P.R.)

Died

June 28, 2024 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.