Tommy Connolly

One of the important currents in the history of early 20th-century baseball is how many immigrants not only embraced their new home but also its national game. Hall of Fame umpire Tommy Connolly stands as a prime example of this fact.

One of the important currents in the history of early 20th-century baseball is how many immigrants not only embraced their new home but also its national game. Hall of Fame umpire Tommy Connolly stands as a prime example of this fact.

Born in Manchester, England, on December 31, 1870, Thomas Henry Connolly immigrated to the United States in 1885. His father was a stonemason and the entire family, except one son who preceded them, came to the US aboard the Canard Liner Servia.1 They settled in Natick, Massachusetts, where his father became a salesman for Catholic church supplies and provided the family with a comfortable living.

Like most young Englishmen, including the famous sportswriter Henry Chadwick, Connolly played cricket while in Great Britain, but had never seen a baseball game before coming to America. In Natick he became batboy for a local team and developed an interest in studying the rules of baseball, reportedly from reading editions of Sporting Life. Unlike many early umpires who took up the profession once their playing days were over, Connolly never played any organized baseball. He turned his interest in baseball and fascination with the rules into a career. His interest in the rules and the knowledge he developed naturally, leading him to a successful umpiring career, both on and off the field. During the early 1890s Connolly umpired for the YMCA Club of Natick. His professional career began in 1894 in the New England League. Umpiring ability aside, ethnic solidarity was a crucial consideration and it was National League umpire Tim Hurst, also of Irish Catholic heritage, who recommended Connolly for his first professional assignment.

Connolly remained in the New England League until 1898, when he joined Hurst in the National League. Umpiring in the major leagues as much an ordeal as it was a job, because of player behavior and the lack of authority. Connolly resigned midway through the 1900 season after multiple disagreements with National League President Nicholas Young, who failed to support some of his on-field rulings. By the end of the year Connolly was officiating in the New York State League.

Fortunately for Connolly’s umpiring career and for Organized Baseball itself, the new American League claimed major-league status. League President Ban Johnson promised umpires he hired that they would receive full support from the league office, and he opposed “rowdyism,” a policy that suited Connolly. Though he had never seen Connolly umpire, Connie Mack, manager of the Philadelphia Athletics and himself an Irish Catholic, recommended that Johnson hire Connolly for the inaugural 1901 season. That began a half-century-plus of service with the junior circuit. Simply put, Tommy Connolly was one of the greatest umpires to ever take the field.

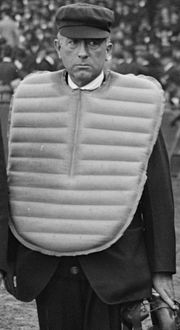

His hiring by Harridge came at a time when nearly every team in the league was unhappy with the quality of umpiring. To address the issue, Connolly instituted many reforms, including scouting the minor leagues for umpiring talent. When a prospect was identified, Connolly would often do the evaluation personally. His career was intertwined with Bill Klem’s; the two men deserve credit for much of the changed status of umpires and umpiring in the major leagues. Most importantly, Connolly created an American League style of umpiring, which resulted in a heated rivalry with his National League counterpart Klem. Most notably, Connolly favored persuasive diplomacy in dealing with controversies and used the outside, “balloon” chest protector, while Klem was an authoritarian presence who insisted on the inside protector.

Because he worked in the league’s first season, it is easy to note Connolly’s career as one of firsts. It is an impressive list, especially when it is understood that his on-field performance justified many of the firsts. Connolly umpired the first American League game when Chicago hosted Cleveland. He later umpired inaugural games at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, Fenway Park in Boston, and Yankee Stadium in the Bronx. He and Hank O’Day were selected to officiate in the first modern World Series, in 1903. Connolly subsequently umpired in seven other fall classics. He umpired in the American League until June 1931, when he retired as a field umpire and was named American League umpire in chief by league President Will Harridge. He served in that post until he retired in January 1954.

He was behind the plate for four no-hitters, including the perfect game pitched by Cleveland’s Addie Joss on October 2, 1908, in which Joss outpitched the Chicago White Sox’ Big Ed Walsh in a 1-0 victory.

Connolly’s baseball career spanned the time from when umpires worked games alone all the way to the modern four-man crews. It also spanned the time from when the profession was not highly regarded to the one that requires formal training and years of on-the-job experience.

Connolly described working alone as not being fun. He was mobbed many times. “Some umpires in those days didn’t dare put the home boys out and I noticed they weren’t around very long,” he said. “They were what we called ‘homers’ and they had short careers.”2

A smallish, slim man (he is reported as 5-feet-7, 170 pounds), Connolly always dressed formally with stiff collars with a tie split by a jeweled stickpin. When asked about his preference for formal dress, Connolly said he dressed carefully because he was representing an important phase of American life. Though not physically imposing, Connolly was able to garner the respect of players by his knowledge of the rules, fairness, and a firm manner. Devoutly religious, he attended Catholic Mass every morning, even during the baseball season.

During the Deadball Era, many umpires made their mark by ejecting players, coaches, managers, and sometimes fans. The primary reason for this was that they were working alone and had to do anything to keep control. In his first year, Connolly tossed 10 players but as he gained experience and respect he seldom had to resort to the thumb. Many accounts of his career note that he umpired 10 years without resorting to an ejection. Ty Cobb respected Connolly and once said, “You can go just so far with Tommy. Once you see his neck get red it’s time to lay off.”3

From 1901 to 1907, Connolly primarily worked games alone and preferred to do so until the time came when the league hired enough umpires to allow for two-man, and later three-man crews. As an umpire supervisor, Connolly was skeptical over the need for a fourth ump, saying three were enough; “…(J)ust perfect…” is how he put it. But the league office won that one.

Despite his preference, Connolly admitted later in his life that solo umpires had their hands full and often could not be in position to make a call. In describing play during the early Deadball days, Connolly said players took advantage of the single-umpire system by leaving base early on fly balls, cutting the second- or third-base corner to gain an edge, tripping base runners, and doing whatever else was required to gain an advantage.

Connolly noted that these tactics almost always caused altercations. He summed up: “An umpire just couldn’t cover every base and everything that happened no matter how alert he was or how hard he tried. But we did the best we could. I have no regrets.”4

Another view of Connolly came from the authors of Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia: “(H)e … believed in the quiet, dignified approach to umpiring, consciously forgoing grandstanding and controversy.”5 Another way of putting it was in Connolly’s off-putting way of describing the umpire. “It may surprise you, but no one ever paid in to a ball park just to watch an umpire.”6

Connolly always stood against rowdyism, and received strong backing from Ban Johnson. In Baltimore in 1901, Joe McGinnity spat tobacco juice in Connolly’s face. Johnson, coming to the umpire’s defense, suspended McGinnity for 12 games.7 Baltimore manager John McGraw, who had long been unhappy with Johnson’s unwavering support of his umpires, eventually left the American League and became manager of the New York Giants the next season.

When he worked alone, Connolly would stay behind the plate when first base was open. With a runner on first, he would move to the back of the pitcher’s mound. But unlike other Deadball Era umpires, Connolly would move back to the plate with a runner on second. Connolly reasoned he would be in better position to see a play at third and of course would then have the plate covered.

On the field Connolly was methodical and far from colorful. He would tell anyone who listened that no one ever bought a ticket to see an umpire. He once tossed Babe Ruth during the Bambino’s early days with Boston. During those days Ruth would often visit with Connolly during the offseason. Anyone familiar with Ruth knows he could not or would not remember a person’s name and almost always referred to people as ‘Kid.’ But that did not apply to Connolly. The Babe would often greet him with “Hi yah, Tommy, you old son of a gun. Remember that day you tossed me?”8

While having a reputation as an excellent mentor for younger umpires, Connolly would also attempt to nurture young players as well. During the debut of a promising rookie who went on to a Hall of Fame career, Tommy called time to talk to the young hurler, who was catching grief from the opposing dugout for the crime of not toeing the mound properly. Going out to the mound, Connolly told the pitcher, “Son, there are right ways and wrong ways to pitch in this league. Let me show you the right way. I’ll take care of that wrecking crew in the dugout and from what you’ve shown me today you’ll be up here a long time.” The rookie pitcher was Gettysburg Eddie Plank, who won over 300 big-league games.9

Another player Connolly encountered was Tris Speaker. In a close play, Speaker blew his top, accusing Connolly of being prejudiced against him and the Indians. Connolly, never raising his voice said, “Tris, you’re out of the game, of course. And if you don’t change your thinking, you’ll be out of baseball.”10

Connolly and the great center fielder did not speak for months, even though Speaker tried to apologize. Later in the season, Speaker wanted Connolly to umpire behind the plate. Connolly agreed. Tris knew that Connolly was the best.11

As an umpire supervisor, Connolly often had to judge talent. Though he was a small man, he preferred umps to have some size. He said a large umpire often makes a good impression on the field and that shorter umpires often have trouble working behind large catchers. He was a stickler on the rules but when asked to list what made a good umpire, he said, “If they’re otherwise all right, what you have to teach them is poise. And another thing I tell ’em is not to have rabbit ears. Never mind that wrecking crew in the dugout. Just go about your job of calling ’em on the field.”12

Former National League President and Commissioner Ford Frick described Connolly this way: “Tommy was a slight quiet little man in an era when most umpires were big, brawny, and boisterous. … He was a religious man too, in an age of violent argument and colorful profanity. … But he had a ready wit and a quiet sense of humor that usually quelled the most serious distractions.”13

Connolly also was a fair judge of playing talent as well. Until his dying day, he would mention two players on his list of all-time greats. He called Walter Johnson the greatest pitcher he had ever seen, and Ty Cobb the best position player because Cobb could “beat you in so many ways.”14

In 1953 Connolly and Klem, the most influential umpires in baseball history, the fathers of their respective league’s umpiring traditions, both of whom were the only ones to have worked in five decades, were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, the first arbiters enshrined among the game’s immortals. He was unable to attend the induction due to illness.

Connolly married Margaret Gavin in 1902 and they had seven children, four daughters and three sons. After Margaret died in 1943, he lived with two of his daughters. Upon his retirement in 1953, Connolly was awarded a gold pass to major-league games and when his schedule and health permitted was often seen at Fenway Park. He died at the age of 90 on April 28, 1961, in Natick of natural causes.

This biography is included in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Baseball Hall of Fame, umpires file Thomas Connolly biography file. Unless otherwise stated, most of the content is from the Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 Ibid.

3 David L. Porter, “Thomas Henry Connolly, Sr.” in Porter, Biographical Dictionary of American Sports (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 109-111.

4 Baseball Hall of Fame, umpires file Thomas Connolly biography file.

5 David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (Kingston, New York: Total Baseball, 2000), 232.

6 Baseball Hall of Fame, umpires file Thomas Connolly biography file.

7 Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The Biographical History of Baseball (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, Inc., 1995), 93.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, February 11, 1954.

11 Ibid.

12 Baseball Hall of Fame, umpires file Thomas Connolly biography file.

13 Ford C. Frick, Games, Asterisks, and People: Memoirs of a Lucky Fan (New York: Crown, 1973), 137.

14 Baseball Hall of Fame, umpires file Thomas Connolly biography file.

Full Name

Thomas Henry Connolly

Born

December 31, 1870 at Manchester, Manchester (GB)

Died

April 28, 1961 at Natick, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.