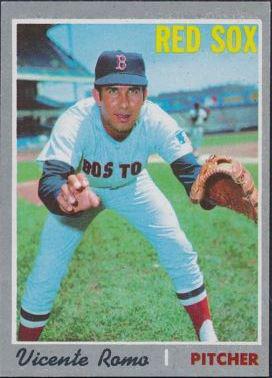

Vicente Romo

Pitcher Vicente Romo won well over 400 games as a professional player from 1961 through 1986.1 Just 32 of those wins came in the majors, where he played during eight seasons (1968-74; 1982) for five teams. Yet many experts in his homeland consider this man the finest right-handed pitcher that Mexico has ever produced — and this status comes from his record at home.

Pitcher Vicente Romo won well over 400 games as a professional player from 1961 through 1986.1 Just 32 of those wins came in the majors, where he played during eight seasons (1968-74; 1982) for five teams. Yet many experts in his homeland consider this man the finest right-handed pitcher that Mexico has ever produced — and this status comes from his record at home.

Over 16 years in Mexico’s summer league, “Huevo” was 182-106 with a 2.49 ERA. He also played 24 seasons in Mexican winter ball. In the history of this league, no one has won more games (182, against 143 losses), posted a better ERA (2.38), or struck out more batters (2,038). In addition, he completed a remarkable 178 of his 364 starts.2 La Liga Mexicana del Pacífico (LMP) awards the Vicente Romo Trophy each year to its best hurler — further proof that he is viewed as his nation’s Cy Young.

Romo became a member of the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame in 1992. His younger brother Enrique Romo, also a pitcher, joined him in 2003. They became the first of just two pairs of brothers to be inducted there. There have also been just two Mexican brother combos in the majors.3

Vicente Romo Navarro was born on April 12, 1943, in Santa Rosalía, a port town in the state of Baja California del Sur. His parents were Santos “Santurria” Romo Urías, a policeman, and Rosario Navarro. Vicente was one of nine children in the family. He had four brothers (Eusebio, José María, and Ramón, as well as Enrique) and four sisters (María Guadalupe, Lidia, Mirsa, and Olga).4 José María, an outfielder, was good enough to play six seasons in the Mexican summer league (1979-84).

In 1952, when Vicente was about nine years old, his family moved to the city of Guaymas, a short boat trip across the Sea of Cortez in the state of Sonora. His love for baseball began then as he saw Abelardo L. Rodríguez Stadium, home of the local ballclub, the Guaymas Ostioneros (Oystermen). “I was swiping baseballs to play, and from there I got the itch. I said to myself that someday I was going to be a baseball player.”5

Romo got his nickname “Huevo” in his youth. It means “Egg” in Spanish and came from the shape of his face, which in those years was perched atop a skinny body.6 His original position was third base, but one day while he was playing in a municipal league, one of his team’s pitchers was absent. Romo took the mound in his place and discovered his true calling.7

The 17-year-old Romo began his pro career with the Oystermen in the winter of 1961-62. At that time Mexico’s winter circuit was known as La Liga Invernal de Sonora. It became known as La Liga Sonora-Sinaloa ahead of the 1965-66 season and adopted its current name, La Liga Mexicana del Pacífico, ahead of the 1970-71 season.

Romo’s most notable performance as a rookie came on November 19, 1961, when he combined on a no-hitter with Emilio Ferrer. Ferrer had to leave the game after being hit by a line drive (one may infer that an error was charged on the play), and Romo pitched the last 6 2/3 innings, allowing just a single walk. It was his first victory as a pro.8 Young Romo went on to be named Rookie of the Year.

Romo was also noticed by Cuban scout Corito Varona, who later signed Fernando Valenzuela (among many other players). “He liked my style,” Romo said. “He signed me for the Mexico City Tigers, and in contrast to today’s million-dollar contracts, he got me for an order of breaded shrimp. All I wanted to do was play.”9

In the summer of 1962 Romo pitched for Aguascalientes in the Mexican Center League, going 8-9 with a 4.47 ERA. After one more winter in Guaymas, he was ready for Mexico’s top summer league. He joined the Mexico City Tigers in 1963 and soon began to gain the attention of U.S. scouts. Dave Garcia, then in the San Francisco Giants organization, praised the hurler after a shutout against first-place Puebla on July 5.10 Romo became this league’s Rookie of the Year as well.

The Cleveland Indians organization purchased Romo’s contract in October 1964. He was assigned to Portland in the Pacific Coast League for the summer of 1965, but did not pitch impressively (2-5, 4.50 in 28 games, largely in relief). Making matters worse, he was on the disabled list for a good part of the season.11 According to a 1968 story, difficulties with language — Romo spoke no English then — were another factor.12

Cleveland arranged for Romo to spend the summer of 1966 back in Mexico City, and he won 17 games, a career high in that league. He then returned Stateside for spring training in 1967– with a personal escort from John Lipon, who’d managed him at Portland in 1965. Romo impressed Indians manager Joe Adcock in his first workout and made the big club’s roster to start the season.13

Before he got into a major-league game, however, he went to Portland once again. Romo later said, “It was very hard, unfortunately — racism touched me, although it was more noticeable towards black players. I was not given the same opportunities that are given today to Mexican ballplayers, because back then U.S. players were preferred. But thanks to Fernando Valenzuela and Teodoro Higuera, who were the ones who opened the doors, people realized fully that yes, there was Mexican talent.”14

Romo’s record at Portland was not impressive (3-11, 4.15), although he was “a victim of non-support most of the season.”15 Nevertheless, the Los Angeles Dodgers thought enough of the prospect to select him from Cleveland in the annual minor-league draft that November. When the news came out, Romo was pitching winter ball. During the 1967-68 season, he posted a minuscule 1.08 ERA and struck out 171 batters in 148 innings — but his won-lost record was just 7-9. Unearned runs (six of the 24 he allowed) may have cost him some games, but his offensive support must have been woeful.

Following spring training with the Dodgers in 1968, Romo again made an Opening Day roster. This time he got into a game. On April 11 at Dodger Stadium, he pitched the ninth inning against the New York Mets, allowing one unearned run to cap a 4-0 loss. That was his only appearance for L.A. that season; near the end of the month, the Dodgers brought up Don Sutton from Triple-A Spokane and returned Romo to the Indians.16

Romo found himself with Portland once more, but pitched well there, thanks in part to some special tutoring from Indians manager Alvin Dark (who’d replaced Adcock) and pitching coach Jack Sanford.17 He got back to Cleveland in late June and never pitched in the U.S. minors again.

Romo was quite active for the Indians over the rest of the 1968 season, appearing in 40 games, all but one in relief. He was highly effective — 5-3, 1.62 with a career-high 12 saves (though just nine were credited under the save rule of the day). Not surprisingly, Cleveland protected him from the expansion draft that fall.

Alvin Dark said in the spring of 1969 that he “absolutely” wouldn’t approve any deal that cost the Indians one of their top six pitchers, a list that included Romo.18 Even so, a week after that article appeared, the pitcher went to Boston as part of the six-player trade that brought Ken “Hawk” Harrelson to Cleveland.

After joining the Red Sox, Romo had eight scoreless outings in a row. “He throws better every time he gets into a game,” said manager Dick Williams, who was thinking of using Romo as a starter.19 That didn’t happen until early August, when Mike Nagy missed a couple of turns with a severe blister.

After two more relief outings came a 36-hour disappearance in Chicago that had the team fearing foul play. At 11 P.M. on August 11, Romo told roommate José Santiago that he was going out for dinner with a male friend. He was not seen until 11 A.M. two days later. Romo said that he had a few drinks, became ill, and “forgot” to inform the team of his condition. Meanwhile, the Chicago police had been looking in hospitals, jails, and morgues.

After Romo returned, Williams went easy on him, docking him only one day’s pay for the game he’d missed. The skipper said, “Vicente can’t afford a big fine on the salary he’s making.”20 From August 17 on, Romo was in the rotation. His last 10 outings of the year included four complete games.

The Red Sox kept Romo out of winter ball in 1969-70, the only such season he missed during his entire career.21 Going into 1970, he was back in the bullpen for Boston. He pitched 38 times in relief that year with just 10 starts, eight of which came in a row during late July and August. He was not nearly as effective, though, averaging less than five innings per start with a 6.56 ERA.

Upon returning to winter ball in the 1970-71 season, Romo became a member of the Ciudad Obregón Yaquis. He set some special marks. First he compiled a streak of 99 2/3 innings without allowing an earned run. Then, on January 5, 1971, he became the first pitcher in league history to throw a perfect game. It came against Guaymas at Abelardo L. Rodríguez Stadium in front of a tiny crowd of just 72 — that afternoon was very cold. “Curves, control, rapid fastballs, and much cleverness,” ran a subhead in one of the local papers.22

Just over a month later, Romo pitched in the Caribbean Series for the first time. This tournament, which pits the region’s winter-league champions against each other, had been revived in 1970. Mexico joined Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela in 1971. Romo was added as a reinforcement (a common practice in winter ball) by the Hermosillo Naranjeros.

On March 31, 1971, Boston traded Romo and Tony Muser to the Chicago White Sox for Duane Josephson and Danny Murphy. Romo got a three-inning save on Opening Day in relief of Tommy John, but his ERA ballooned after a few bad outings. Romo’s only two starts of the year went poorly, which also affected his record, but overall he pitched much better in the second half. He allowed just one run in his last 19 outings and trimmed his ERA to 3.38 in 45 games.

Romo appeared just 28 times for the White Sox in 1972, missing nearly all of August with a sore arm.23 After the season he was traded to the San Diego Padres for Johnny Jeter. He spent two years with the Padres, who finished last in the National League West in both, posting identical records of 60-102. Romo pitched in 103 games, starting twice, with overall marks of 7-8, 4.08, and 16 saves. San Diego was a convenient location for Romo, fairly near his home in Mexico. “He’d go home on Sunday afternoon and wouldn’t show up at the park again until Wednesday,” said his teammate in 1973, Pat Corrales.24

The Sporting News wrote in October 1974, “It is no secret in the majors that the Padres will make wholesale changes this fall and winter.” Romo was named as one of the players sure to go.25 He stuck around until the end of March 1975, when San Diego finally released him.

Romo then returned to Mexico for summer ball, joining a new team, the Córdoba Cafeteros. He pitched with the Coffeegrowers through 1978. The team featured several former big-leaguers, among them Juan Pizarro, who’d gone to Cleveland as part of the Hawk Harrelson deal that involved Romo. Vicente’s brother Enrique was an opponent with the Mexico City Reds in 1975 and 1976 before moving to the majors. Another opponent was former Red Sox teammate Mike Nagy.

Romo pitched for the Coatzacoalcos Azules (Blues) from 1979 through 1981. His 1979 season was remarkable: Despite a won-lost record of 14-13, he threw 10 shutouts to tie a league record set by American Gary Ryerson in 1976 and equaled by Luis Gómez in 1977.

Then, at the age of 39 in 1982, Romo returned to the big leagues after an absence of seven years. He later called it the most satisfying thing he’d accomplished in the majors.26 The previous winter, scout Wilfredo Calviño had signed Romo for the St. Louis Cardinals, who invited him to spring training, where he pitched effectively but was the last man cut. Chuck Tanner, who’d managed Romo with the White Sox, quipped, “It came down to Romo and Jim Kaat. They kept Kaat because he’s younger.” Kaat was then 43!27

Then, at the age of 39 in 1982, Romo returned to the big leagues after an absence of seven years. He later called it the most satisfying thing he’d accomplished in the majors.26 The previous winter, scout Wilfredo Calviño had signed Romo for the St. Louis Cardinals, who invited him to spring training, where he pitched effectively but was the last man cut. Chuck Tanner, who’d managed Romo with the White Sox, quipped, “It came down to Romo and Jim Kaat. They kept Kaat because he’s younger.” Kaat was then 43!27

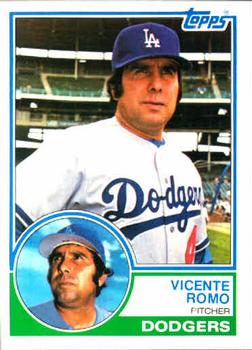

Romo returned to Coatzacoalcos after refusing to accept a Triple-A contract. He got off to a sizzling start (7-0, 1.54), and the Dodgers signed him in May. Initially he replaced Burt Hooton, who’d been placed on the disabled list. Romo had expected a call from L.A. long before that — Dodgers scout Mike Brito had been telling him for years that the team would bring him back. Romo was assigned a locker next to fellow Mexican Fernando Valenzuela.28

Romo appeared in 15 games for L.A. and posted a record of 1-2, 3.03. On June 2 at Pittsburgh, he and brother Enrique appeared in the same big-league game for the only time. Vicente picked up the last of his 52 big-league saves on June 18. His win came on July 19 over Montreal in one of his six starts; it was his first big-league victory in that capacity since April 1970. He went seven scoreless innings — striking out six on an “assortment of forkballs, curves, sliders, changeups and not-so-hard fastballs” — and Steve Howe finished up.29

“He’s got a lot left as far as I’m concerned,” said Al Oliver of the Expos. “It’s not how hard you throw, it’s where you throw it. If you’ve got good location, you’re gonna win. He’s got all the pitches. You can’t go up there and expect any one. You’ve just gotta be quick and hope.”30

Unfortunately, Romo’s last appearance in the majors came eight days later, on July 27. In the second inning of a start against the Giants at Candlestick Park, he suffered a partially torn patellar tendon. Soon thereafter, he underwent season-ending surgery.31 He returned to Mexico in 1983, leaving his lifetime marks in the majors at 32-33 with an ERA of 3.36 in 645 2/3 innings.

As late as 1984, however, major-league clubs were still interested in Romo. The California Angels invited him to spring training that year; reportedly he’d picked up a screwball, prompting one Angels executive to say, “If he’s Mexican and throws a screwball, we don’t care how old he is.” Romo was hit hard, though, and released early in camp.32

The veteran pitched on in Mexico, though his workload was lighter. His last season in the LMP was the winter of 1985-86, and his playing career ended after the summer of 1986, when he was 43 years old.

Romo was never a member of a champion team in Mexico’s summer league. He missed out on the Mexico City Tigers’ title in 1965 while pitching for Portland. In the LMP, however, he played for six champions.33 In addition, because Hermosillo called on him four times as a reinforcement, he took part in nine Caribbean Series, with totals of 5-3, 3.30 in 62 2/3 innings pitched.34 The most memorable of those opportunities was in 1976, when Mexico won the tournament for the first time. Romo contributed a win.

Romo called his wife, Sara Armenta, “the biggest thing I’ve had in my life after God and my parents. She’s my great companion and has been with me in the best and worst moments of my life, supporting me.” They had two daughters. Kenia married a ballplayer named Flavio Romero, who had a long career in Mexico starting in 2000. Her sister was named Karla.35

The Ciudad Obregón Yaquis bestowed a unique honor on Vicente and Enrique Romo in November 2010, retiring their uniform numbers simultaneously. Vicente also received this honor from the Culiacán Tomateros in December 2011.36 He’d joined that club starting in the winter of 1974-75 and played 11 winter seasons with them.

A couple of years later, in December 2013, the Romo brothers faced each other in a “Legends of Baseball” game in Guaymas. It featured active major leaguer Luis Ayala and at least one other MLB vet, Sid Monge. Enrique’s side won, 13-9, and he got credit for the victory. Enrique had won all five matchups against Vicente during their professional careers, and before the game, he had joked, “I see it being difficult for him to beat me, if he could not at his best!”37

Vicente Romo has been a pitching coach for various Mexican teams over the years. He remained active in baseball as of the LMP’s 2017-18 winter season, serving as bullpen coach for Venados de Mazatlán.38

Last revised: October 19, 2017

Acknowledgments

Continued thanks to Jesús Alberto Rubio in Mexico. This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted the following:

Books

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor. Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition), 2011.

Guía Oficial LMP, 2013-14.

Internet

comc.com.

Notes

1 Along with his record in the majors, Mexico’s top summer league, and Mexican winter ball, this total also includes 17 wins in minor leagues in the U.S. (nine) and Mexico (eight). Aside from his record in the Caribbean Series, it has not been possible to determine how many wins he recorded in postseason play.

2 Manuel de Jesús Sortillón Valenzuela, “Vicente Romo Navarro: Un Brazo de Acero,” Historia de Hermosillo website.

3 The other pair of brothers in the Mexican Hall of Fame, as of 2017, is Aurelio Rodríguez and his older brother Juan Francisco. Juan Francisco Rodríguez never played in the majors. Neither did some other Mexican major-leaguers’ siblings who had worthy pro careers. One example is Mel Almada, whose brother Lou might have become the first Mexican-born player in the majors, but Lou got hurt after making the Opening Day roster of the New York Giants in 1927. Another is Andrés Mora, whose brother Jesús played in the Mexican League from 1968-79. So, the only other pair of Mexican brothers to play in the majors has been Carlos “Bobby” Treviño and Alex Treviño.

4 Gilberto Castro Meza, “Rinden merecido homenaje con una placa al Huevo Romo,” El Sudcaliforniano (La Paz, Baja California del Sur, Mexico), December 20, 2010. Gilberto Castro Meza, “Montarán una plaza alusiva en la casa donde nació ‘Huevo’ Romo,” El Sudcaliforniano, October 27, 2009.

5 Yesenia Torrecillas, “Vicente ‘Huevo’ Romo: El Cy Young Mexicano,” originally published on Pelotapimienta.mx, March 6, 2014 (pelotapimienta.mx/vicente-huevo-romo-el-cy-young-mexicano). This site is no longer operating, but the story is visible on other sites.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Alfonso Araujo, “Los Romo,” TVPacífico.com.mx, September 11, 2015. Alfonso Araujo, “Lanzando para Home,” Pasandolabola.com, August 28, 2008. Sr. Araujo, one of his nation’s foremost baseball writers, also became a member of the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame (1997).

9 Torrecillas, “Vicente ‘Huevo’ Romo: El Cy Young Mexicano.”

10 “Mexican League,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1963, 43.

11 Roberto Hernandez, “Mexico City’s Tigers Picked to Keep Title,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1966, 34.

12 Russell Schneider, “Injuns Click Heels over Romo’s Work in Toeplate Drama,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1968, 8.

13 “Rocky Terminates Holdout, Avoids a Full 25 Pct. Slice,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1967, 30. Russell Schneider, “Duke Earns Rating as Wigwam Royalty,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1967, 21.

14 Torrecillas, “Vicente ‘Huevo’ Romo: El Cy Young Mexicano.”

15 “Coast Clippings — Luckless Romo,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1967, 42.

16 Bob Hunter, “Dodgers Plain Poison in Late Innings,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1968, 20.

17 Schneider, “Injuns Click Heels over Romo’s Work in Toeplate Drama.”

18 Russell Schneider, “New Tribe Hallmark Includes Jim in LF,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1969, 25.

19 “Major Flashes — American League,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1969, 25.

20 Larry Claflin, “Roaming Romo’s Disappearing Act…What Next for Sad Sox?” The Sporting News, August 30, 1969, 19.

21 Fernando Ballesteros, “‘Huevo’ Romo — el día que poncho a Mickey Mantle,” Puro Beisbol website, April 4, 2013.

22 Francisco Rodríguez, “Vicente Romo Lanzó Juego Perfecto, 12-0,” El Imparcial (Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico), January 6, 1972

23 Edgar Munzel, “Drabowsky and Fisher Beef Pale Hose Bullpen,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1972, 11.

24 Bill Conlin, “Is Seaver’s Slump Cause for Concern?” The Sporting News, June 7, 1982, 35.

25 Phil Collier, “Padres Lack ‘Something’ — Yea, Verily,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1974, 14.

26 Information from Jesús Alberto Rubio’s files.

27 Stan Isle, “Around the Horn,” The Sporting News, June 14, 1982, 8.

28 Rick Hummel, “Romo Gets Chance with Cardinals,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 15, 1982. “Dodgers Paying a Tough Price,” Los Angeles Times, May 28, 1982. Gordon Verrell, “Guerrero Glistens While Others Fail,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1982, 36. Vic West, “Dodgers get more help from Mexico; Romo beats Expos,” San Bernardino County Sun, July 20, 1982, 29.

29 West, “Dodgers get more help from Mexico; Romo beats Expos.”

30 Ibid.

31 “Dodgers’ Romo needs knee surgery,” Associated Press, July 29, 1982.

32 Tom Singer, “Lynn Yields to Swift Pettis,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1984, 42. Tom Singer, “Aggressive Promotions Planned,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1984, 38. Tom Singer, “Reggie, John Ease McNamara’s Worries,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1984, 20.

33 They were: Guaymas (1962-63; 1964-65), Ciudad Obregón (1972-73), and Culiacán (1977-78, 1982-83, 1984-85). If Romo hadn’t been traded from Guaymas to Cañeros de Los Mochis during the 1967-68 season, it would have been seven. (That was the only time he spent with Los Mochis.)

34 Alfonso Araujo Bojórquez, Series del Caribe: Narraciones y Estadísticas, 1949-2001, Volume 2, Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico: Colegio de Bachilleres del Estado de Sinaloa, 2002, 200.

35 Rubio interview.

36 de Jesús, “Vicente Romo Navarro: Un Brazo de Acero.”

37 Jorge Castillo Morán, “Vivirá Guaymas histórico y fraternal duelo de béisbol,” El Vigia (Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico), December 4, 2013. Game account with photos, Deportivas regionales de Jorge Castillo Morán, the journalist’s Facebook page, December 16, 2013.

38 “Vicente Romo ve un cuerpo de pitcheo sólido,” Punto.mx, September 21, 2017.

Full Name

Vicente Romo Navarro

Born

April 12, 1943 at Santa Rosalia, Baja California Sur (Mexico)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.