Sam Kimber

Samuel Jackson Kimber’s childhood might have been the stuff of a Dickens novel and his short but distinctive major-league pitching career the scaffolding for a film script. He was born in Philadelphia to Richard R. and Sarah (Jaret) Kimber on October 29, 1852.1 His father worked as a paper stainer but died suddenly the day before Sam’s first birthday, on October 28, 1853, of a hemorrhage. Left to struggle as a single parent, Sarah Kimber appears to have died in 1859 of unknown causes, orphaning young Sam. He was soon thereafter placed in Girard College in Philadelphia, “a school for poor, orphaned or fatherless white boys who would live on campus.”2 Kimber is registered as an “inmate” at the school in the 1860 US Census.3

Samuel Jackson Kimber’s childhood might have been the stuff of a Dickens novel and his short but distinctive major-league pitching career the scaffolding for a film script. He was born in Philadelphia to Richard R. and Sarah (Jaret) Kimber on October 29, 1852.1 His father worked as a paper stainer but died suddenly the day before Sam’s first birthday, on October 28, 1853, of a hemorrhage. Left to struggle as a single parent, Sarah Kimber appears to have died in 1859 of unknown causes, orphaning young Sam. He was soon thereafter placed in Girard College in Philadelphia, “a school for poor, orphaned or fatherless white boys who would live on campus.”2 Kimber is registered as an “inmate” at the school in the 1860 US Census.3

Girard in the 1860s was a dreary station for a young boy, but it had one saving grace. Baseball was a popular sport among the inmates. Led by Lon Knight, an outfielder and pitcher who first began making a living at the diamond sport in the mid-1870s, Girard had produced an abundance of professional ballplayers by the end of the 19th century, and Kimber proved to be one of them although none might have predicted his success at the game during his years at the orphanage school. The circumstances that enabled him to leave Girard are unknown, as are his movements in the 1870s after he can be presumed to have struck out on his own at age 18 or so. But by the time he was 28, when the 1880 census was taken, he was working purportedly as a blacksmith and living with his wife, Sarah (Kelley) Kimber, like him a native of Philadelphia. They had a young son, William, born in June 1879. Kimber seems to have abandoned blacksmithing soon after the 1880 census and begun working as a laborer in Philadelphia. He nonetheless still found time to play baseball, albeit only at the sandlot or amateur level. Samuel Jr., the couple’s second child, was born in 1881 and a daughter, Sadie, joined the family in 1888.

Kimber continued to hurl on his days off for a string of local amateur and semipro clubs in Philadelphia until he was past 30. If he had ever entertained professional aspirations, his time to explore them seemingly had come and gone. Moreover, thus far nothing has emerged to suggest that he cut much of a swath in Philadelphia amateur or semipro circles. He may in fact have been a virtual nonentity. Yet he suddenly appears to have tried to shave two years off his birth date –some sources have listed his birth year as 1854 — in an effort to appeal to one of the burgeoning number of professional teams in the Philadelphia area. The ruse succeeded in gaining him a pitching post with the powerful Merritt club of Camden, New Jersey, at age 28 (really 30) in 1883. What’s more, he swiftly made the most of his chance, displaying talents in the box that heretofore had never received public mention. He went to the Brooklyn Greys of the Interstate Association in July when the Merritts disbanded while leading the IA by a comfortable margin. Kimber had been 14-3 with Camden and was subsequently 14-7 with Brooklyn, enabling him to finish the season a composite 28-10 with the two clubs, with a combined (retrospective) 1.27 earned-run average.

The 5-foot-10½, 165-pound right-hander accompanied Brooklyn when it joined the major-league American Association in 1884. The Brooklyns, known at the time as the Greys, are the distant predecessors of the present-day Los Angeles Dodgers franchise. Kimber started the franchise’s first game as a major-league entity on May 1, 1884, working under manager George Taylor at Brooklyn’s Washington Park. He lost egregiously to Washington rookie John Hamill in a 12-0 blowout. For Hamill, it was his best day; he finished his one and only big-league season with a 2-17 record. Kimber quickly turned himself around and emerged as the Brooklyn staff ace, winning 18 games for a team that finished ninth in a 12-franchise league with a 40-64 record. He missed his 19th win and a chance to finish with a .500 record for a poor second-division club when he lost his final start of the season to Cincinnati, 5-2, on October 13.

On October 4, 1884, Kimber achieved a famous first that has never been equaled. It was on his home ground in Brooklyn when he was caught by fellow rookie Jack Corcoran and held eighth-place Toledo hitless for 10 innings before the game was called by darkness with the score still 0-0 as his teammates managed just four hits off Toledo’s kingpin, Tony Mullane.4 Kimber’s achievement was not only the first extra-inning no-hitter in professional baseball history but through 2015 he remained the only hurler to fashion a major-league complete-game no-hitter of nine or more innings without being credited with a decision.

Brooklyn reserved Kimber for 1885 but then cast him adrift along with most of its regular 1884 cast when it bought out the disbanding Cleveland National League team in order to acquire the majority of its players deemed more desirable. In most times, his 18 wins and the monumental no-hitter as a rookie would almost certainly have earned him a shot with another major-league team, but the aftermath of the 1884 season was one of a kind. With the major leagues reduced from 28 franchises to just 16 after the rebel Union Association threw in the towel after just one season and the American Association cut its ranks from 12 teams to eight for 1885, major-league pitching jobs were reduced by 40 percent. Kimber thus began 1885 with the Virginia club of the Eastern League but was dropped in August with a 28-8 ledger. It was scarcely a month after he fashioned an 8-0 no-hit win against Alexandria, Virginia, on July 22 in which he was caught by his old Brooklyn batterymate Corcoran and registered just one strikeout. Kimber added icing to the cake by hammering a gigantic three-run homer over the distant center-field fence in Alexandria, the first man ever to accomplish that feat.5

After leaving the Virginias, Kimber joined the Newark club in the same loop and was 3-3 with the New Jersey entry when the 1885 Eastern League season ended. His final major-league game, in answer to an emergency summons from the pitching-depleted Providence Grays (who were already on the brink of folding even though the 1885 National League season had not yet closed), is best forgotten, as he lost 13-1 at Detroit to Wolverines lefty Lady Baldwin on September 29.

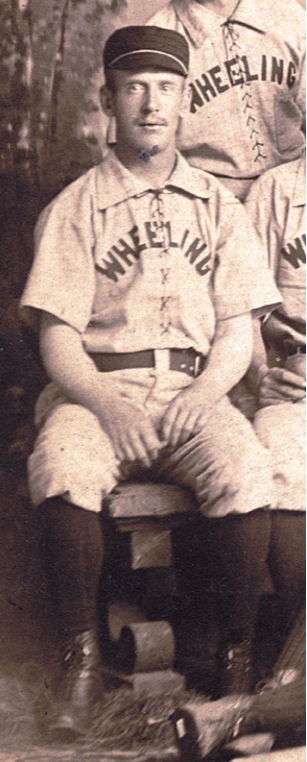

In light of what transpired over the remainder of Kimber’s professional baseball career, one can reasonably surmise that his precipitous decline late in the 1885 campaign was the result of an injury, quite possibility to his arm, as he was never again a commanding pitcher. He began the 1886 season with Atlanta of the Southern League but was ineffective and finished the year with Williamsport of the Pennsylvania State Association. Kimber then pitched two more seasons in the lower minors before turning his offseason job driving a streetcar in Philadelphia into a full-time profession for a time. In his first season, spent mostly with Wheeling, West Virginia, of the Ohio State League, he experienced a climate of discontent in midsummer when members of the Nail Cities were publicly accused by local fans of playing to lose. The controversy was highlighted for several days in the Wheeling Register and quickly put to rest when Parson Nicholson, who had replaced the unpopular John Crogan as player-manager, published a letter in the July 29, 1887, edition of the Register avowing his club’s honesty. The letter drew ardent support from his entire team, including Kimber.6

Kimber returned to Wheeling for the 1888 season. The Nail Cities were now in the Tri-State League under player-manager Al Buckenberger and had pennant aspirations (they ultimately finished second). After winning six of his first 10 starts Kimber was summarily released when Buckenberger suspected him of coveting the club’s managerial post. Owing to a bizarre rule the Tri-State League legislated in the spring of 1888 (to the dismay of other minor-league circuits) that prohibited any other league from signing a player released by a Tri-State entry until the 1888 season closed, Kimber sat idle for several weeks at his home in Philadelphia.7 He hooked on later in the summer with Portland, Maine, of the New England League but dropped his professional aspirations entirely after losing four straight starts. Earlier, while still active in the game, Kimber had spent his winters working as a watchman (what we might now call a security guard) in various Philadelphia mills. He seems to have found steady work as a watchman with the railroad sometime in the first decade of the new century and worked as such for the remainder of his life.

Kimber died of bronchial pneumonia brought on by influenza, in Philadelphia on November 6, 1925, at age 73.

This biography appears in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Her surname is also found rendered as Jarett, and might today more typically be spelled Jarrett.

2 http://girardcollege.com/page.cfm?p=359.

3 He is listed as a laborer in the Philadelphia City Directory in 1882 and as late as 1890.

4 Sporting Life, October 11, 1884: 4.

5 Sporting Life, July 29, 1885: 2.

6 “The Bobbies Win,” Wheeling Register, July 29, 1887: 4.

7 Sporting Life, August 29, 1888: 1; under pressure the Tri-State League lifted the ban on signing any of its released players before the 1888 season ended.

Full Name

Samuel Jackson Kimber

Born

October 29, 1852 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

November 6, 1925 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.