Parson Nicholson

A strong keystone combination is considered essential for a good team. Before there was Whitaker and Trammell, before The Wizard and Tommy Herr, before Tinker and Evers (and Chance), there was Nicholson and Scheibeck. Who, you ask? In 1890, Parson Nicholson and Frank Scheibeck became just the third major league combo to start every game for their club at second base and shortstop, respectively.

A strong keystone combination is considered essential for a good team. Before there was Whitaker and Trammell, before The Wizard and Tommy Herr, before Tinker and Evers (and Chance), there was Nicholson and Scheibeck. Who, you ask? In 1890, Parson Nicholson and Frank Scheibeck became just the third major league combo to start every game for their club at second base and shortstop, respectively.

In 1876, the first year of the National League, shortstop John Peters had teamed up with Ross Barnes at second base to play in all 66 games for the Chicago White Stockings.1 Three seasons later, Peters teamed up with Joe Quest at second base, and the pair played every inning of all 83 games as the keystone combination for the White Stockings. That was it until 1890, when Toledo joined the American Association, bringing Nicholson and Scheibeck with them.2 Scheibeck played all 1,159 innings of Toledo’s 134 games at shortstop. Nicholson played 1,149 innings at second base, starting all 134 games.3 That same season, Hub Collins and Germany Smith shared every inning (all 1,144 of them) of all 129 games for Brooklyn at second base and shortstop, respectively. The feat was accomplished twice more the following season, and that was all for the nineteenth century – just six times when two teammates started every game for their club at the keystone combination.4

Thomas Clark Nicholson was born on April 14, 1863, in Blaine, Ohio, the first of three children of William and Jane (Dixon) Nicholson. Both his parents were descended from English immigrants. His mother died when Thomas was six. The family then lived in Bellaire, Ohio, where his father was a machinist and Thomas was identified as a nail feeder in the 1880 Census (likely at the LaBelle Nail Factory). He first appeared in box scores catching and playing second base for the Belleaire Globes in 1883 through 1885.5

At the age of 23, 1886 was his coming out year. He played with Bellaire again before stints with Steubenville, Ohio, and Wheeling, West Virginia (just across the Ohio River from Bellaire) in the Ohio State League, and Barnesville, Ohio (an independent club). There are also reports that he played for Zanesville, Ohio, in the Ohio State League and caught for a club in Wooster, Ohio, that summer.6 He topped off the year by marrying Lizzie Blamey in November of 1886.7

In 1887, Nicholson started the season as the manager of the Steubenville club in the Ohio State League. “The newspapers have begun to designate our own Tom Nicholson, manager of the Steubenville club, as Parson, but this is all to his credit. Tommy is not a man of the wicked world even if he is an expert ball player.”8 After Steubenville folded in late June, Nicholson was signed by the club in Wheeling, West Virginia. Within a week he was promoted to the manager of that club.

“Everyone knows who Nicholson is; he is the valuable second baseman and general player, secured when Steubenville disbanded. He is a Bellaire man, one of excellent habits, with a cool head and good judgement. He is a hard, conscientious worker, and is firm enough to see to it that those under him do the proper thing or else be punished for a neglect to do it.”9

Immediately after Nicholson joined Wheeling, future Hall of Famer Sol White was signed to play third base.10 White had been a teammate and friend of Nicholson’s with the Globes in 1885 and 1886. Nicholson hit .357 combined between Steubenville and Wheeling, catching the attention of the St. Louis Browns.

In late September 1887, Parson Nicholson got the chance of a lifetime – an opportunity to play in the World Series. The American Association champion St. Louis Browns were looking for a second baseman to fill in for Yank Robinson, whose hand had been spiked in a game earlier in the month. “Nicholson received a telegram from St. Louis inquiring what he would ask to play with the Browns through their games with Detroit. He wired back naming $300.”11 Nicholson must not have realized he was dealing with Chris Von der Ahe, who was notoriously cheap. Von der Ahe signed Harry Lyons instead. Robinson played in the bulk of the games for the Browns in their World Series against the National League champion Detroit Wolverines, with Lyons just playing in just two of them. Detroit won the series, 10 games to 5. Perhaps if Nicholson had asked for only $250, the outcome of the series might have been different. Nicholson ultimately signed with the Browns in late October 1887, too late to play in the Series.

When Nicholson arrived in St. Louis at the end of March 1888 for spring training, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, he was going to tower over the other players: “Probably the most prominent of the young players who will be seen on the Brown Stocking team this year is T. C. Nicholson. He is 25 years of age, is 6 feet 6 inches in height, and weighs about 190 pounds… [he] made his debut as a ball player with the Bellaire Club, the strongest amateur organization in Eastern Ohio.”12 Nicholson’s official height and weight are given as 5’9” and 148 lbs. If he were 6’6”, that would make him taller than Cal Ripken (6’4”).

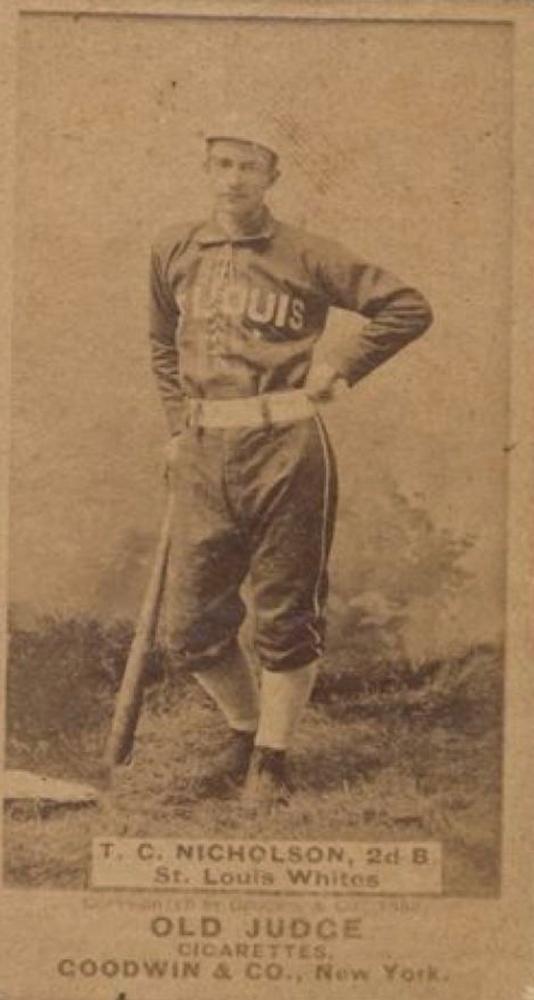

The Browns opened spring training with four games against the St. Louis Whites, Von der Ahe’s entry into the new Class A minor Western Association.13 Nicholson sat the first two games, and played right field for the Whites in the third and fourth games. When the Browns left on a road trip to Memphis and New Orleans, Nicholson stayed behind and continued playing with the Whites. The Browns had Robinson returning to play shortstop and had traded for Chippy McGarr in the off-season; McGarr would be the second baseman at the start of the season. Lyons was kept as a backup; he played 123 games, mostly in the outfield. Nicholson was the odd man out. He was formally transferred to the Whites towards the end of April.14 He batted leadoff while playing mostly second base or right field for every one of the Whites’ 39 games, hitting .276, second highest on the club behind Jake Beckley.

After the Whites disbanded, Nicholson returned home to his wife and son George (born in April 1887) to play for the club in Wheeling. He was purchased from Wheeling by Detroit on September 12, 1888, for $400 after several weeks of negotiations between the two clubs.15

Nicholson made his major league debut on September 14 against Philadelphia, playing second base and batting last in the lineup.16 He singled in his first at bat and scored on a hit by Deacon White. He made a good impression in the field (4 assists, no errors). “He picks up a ball neatly and throws quickly. His first chance was a difficult one, being a short bound, but he handled it as though he was used to that sort of thing.”17 Detroit won, 7-5, with Philadelphia pitcher Dan Casey imitating “a humorous song entitled ‘Casey at the Bat’” by grounding out with the tying runs on base to end the game. The wire story for the game noted, “Nicholson, Detroit’s new second baseman, made a good impression, notwithstanding his evident nervousness.”18

Nicholson played the remainder of the season at second base for Detroit. On October 13, 1888, he hit the first of his five career home runs, off Hank O’Day of Washington.19 In his brief time in Detroit, he hit .259 and made eight errors in 123 chances. When the season ended, the Detroit club sold off its players and folded. Nicholson was sold to Cleveland, who moved from the American Association to the National League for the 1889 season. He went to spring training with Cleveland but returned home in May when his grandmother became ill. While he was in Bellaire, Cleveland worked out a deal to sell him to Columbus in the American Association, but when Nicholson remained at home until after his grandmother died, he was instead sold to Toledo in the International League. He appeared in 87 games, hitting .302, with 39 stolen bases, 18 doubles and seven triples. His fielding, playing shortstop, was not so good – 65 errors in 87 games, for an .851 fielding percentage.20

Nicholson’s only full year in the majors was 1890. The American Association was weakened by the loss of teams and players due to the war with the Players League. Cincinnati, one of the founding clubs, jumped to the National League for the 1890 season along with 1889 Association champion Brooklyn. Baltimore, another of the founding clubs, moved to the Atlantic Association, while Kansas City moved back to the Western Association. Needing four clubs, the American Association recruited clubs from Syracuse, Rochester and Toledo, and established a new club in Brooklyn.21 Nicholson came along with the Toledo club. He played in every one of Toledo’s 134 games at second base (with two innings behind the plate) and hit .268 for the fourth-place club. At the conclusion of the season, the Players League collapsed, and the American Association kicked out the three clubs it had added for 1890 – Rochester, Syracuse, and Toledo.

Out of the majors again, Nicholson signed with Sioux City in the Western Association for 1891. After the season, the pennant winners won a series against the Chicago White Stockings, 4 games to 2, and another against the St. Louis Browns, winning 5-0. Nicholson had six hits (two doubles and a triple) in the five games against the Browns, who then signed him for a reported salary of $3500.22 But two weeks into spring training he was released and signed with Toledo in the fledgling Class A Western League, as manager and second baseman. When the league folded in July, he bounced to Joliet (Illinois) in the lowly Class F Illinois-Iowa League, then finished the season with Chattanooga (Tennessee) in the Class B Southern League. After returning home to Bellaire for the winter to run his shoe store, Nicholson signed to play for the Erie (Pennsylvania) Blackbirds of the Class A Eastern League for 1893 and hit .306. When he hit .333 there in 1894, the Washington Senators drafted him.23

Nicholson opened the 1895 season at shortstop and leading off for Washington on April 19 at Boston. He was 1-for-5, a bunt single in the third inning, after which he scored on a home run by Charlie Abbey. But after nine games he was batting eighth. After ten games he was hitting .184 and had made 13 errors in 64 chances. His 168-game major league career ended when the Senators released him to Detroit in the reconstituted Western League, where he was to pair with Frank Scheibeck again. “This story going the rounds that Nick has a glass arm is fake,” Scheibeck said. “He and I have played together, and I know he’s all right. With him on second we will make some of our old-time plays. [Washington manager Gus] Schmelz played him out of position at short. The parson is a much better second baseman than Crooks.”24

Nicholson returned to Detroit in 1896, playing in 129 games and hitting .286. His fielding percentage of .931 was second best among second basemen in the league with more than 30 games.25 He was reserved for 1897, but by January it seems he was no longer expected to have a spot on the club for the coming season. He finally came to terms with Detroit in April in time for the start of the season, but he was never more than a backup for the club before being released in mid-May. He remained in Detroit, where he played in five games for Minneapolis against Detroit while Pete Cassidy was recovering from a sore wrist. After Minnesota left town, Charles Comiskey (who undoubtedly knew Nicholson from his days with the Whites) signed Nicholson to play second base for St. Paul. Less than one month after that, he was sold to Kansas City. Of this sojourn through the Western League, the Detroit Free Press noted in late July “‘Parson’ Nicholson has not yet played with Indianapolis, Columbus or Milwaukee, but the season is little more than half gone.”26

Despite numerous reports of his imminent release, the 34-year-old Nicholson remained with the Blues through the end of the season. On September 9, he recorded two of the three outs in a triple play against Minneapolis. “In the sixth inning, with [Frank] Eustace on second and Doggie] Miller on first, Tom] Letcher drove a terrific one at Pop Nicholson, who caught the ball with one hand, touched second and threw to first ahead of Miller, retiring the side. It was a brilliant play and Pop received an ovation.”27 Nicholson hit .296 in 111 games across the four clubs, with 24 doubles, ten triples, and one home run.

Over the off-season, it seemed that Nicholson might retire. There was speculation that he would run for mayor of Bellaire.28 However, he re-signed with Kansas City in early April for the 1898 season. He was released just three weeks into the season after Frank Connaughton ended his holdout. “[Parson] has always been popular in Kansas City, as he is a clean, conscientious player, who always gives the best there is in him. He is, however, hardly fast enough to keep up with the lively youngsters who compose the infield of the Blues at the present.”29 On his way back to Bellaire, he stopped in Zanesville to play for the club there in the Class F Ohio State League.30 The league folded while Zanesville was in Wheeling, and Nicholson crossed the Ohio River back home to Bellaire.31 He was lured out of retirement in August to finish the season with the Newark, New Jersey, club in the Class B Atlantic League.

Nicholson sought to come back for one more season in 1899. “Parson Nicholson must be in love with the national game, as he refuses to stay out of it although his joints are stiff and his step too slow for the youngsters who make names for themselves in the minor leagues. Nicholson has signed with Wheeling in the Class B Inter-State League.”32 He did not start the season with the club; instead, he joined the umpiring staff for the Inter-State League. In July, he stopped umpiring to play for Dayton. “Parson Nicholson, the veteran second baseman, who has been umpiring in this league, has donned the spangles again. He was on the Dayton bench the other day in uniform, and was sent in to bat in the ninth. He was given a great reception and the fans would have been glad if he had made a hit. As it was, he fouled out.”33 Nicholson barely had time to settle in Dayton before taking the job as the Wheeling manager at the end of July. The club was sold to new owners in August, and Nicholson was laid off.34 He played in just 15 games with Wheeling and hit just .140.35

During his career in baseball, Nicholson entered into a partnership to open a shoe store, to which he would return during the off-season. His fifth and final child, daughter Esther, was born in March 1899. After his playing career ended, he returned to his business full time. He ran unsuccessfully for Bellaire city treasurer in 1900, and subsequently worked as an enumerator for the census that summer.36 In 1903 he was elected mayor of Bellaire, a position he held through 1905. He ultimately owned shoe repair shops in Bellaire and Wheeling. He died of bronchial pneumonia on February 28, 1917, at the age of 57, survived by his wife and five children. He is buried with wife Elizabeth in Greenwood Cemetery in Bellaire, Ohio.

Parson Nicholson was well respected as a player and manager. When he was hired to manage Wheeling in 1899, the Wheeling Intelligencer wrote, “He is a gentleman in every sense of the word, and his large experience in the sport will stand him well at this critical period in the history of the Wheeling team.”37 When he was fired just a few weeks later, the paper wrote, “The release of Nicholson and O’Hara is not especially well received by the fans.”38 At his peak, he was a reliable fielder and solid hitter. His career seemed more defined by lack of opportunity at the major league level than lack of success or talent. If he had asked for less money in the fall of 1887 … youneverknow.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

US Census data was accessed through GenealogyBank.com and Ancestry.com, and other family information was found at Ancestry.com and FindAGrave.com. Stats and records were collected from Baseball-Reference unless otherwise noted. Stats and records from some seasons were found in the annual Spalding’s Base Ball Guides. Articles cited in this biography were typically accessed through Newspapers.com and/or GenealogyBank.com. Street guides were accessed through Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Cap Anson joined the pair playing in all 66 games at third base as the White Stockings (52-14) finished first in the inaugural season of the National League. Barnes and Peters each pitched one inning during the season; Paul Hines filled in for two innings at second base, while Al Spalding played one inning at shortstop.

2 Toledo played in the minor leagues prior to 1890 (in the International League in 1889 and the Tri-State League in 1888). A club representing Toledo played in the American Association in 1884; that club folded after spending the 1885 season in the Western League.

3 Bill Van Dyke appeared at second base in eleven innings over two games.

4 In 1891, Germany Smith and Bid McPhee played all 1,218 innings of 138 games for Cincinnati, while and Ed McKean and Cupid Childs missed just one of the 1243 innings in 141 games for Cleveland.

5 Nicholson is known to have played with the Globes in 1885, and it is likely that the Nicholson in the box scores for the Globes in 1883 and 1884 was also him.

6 “Bellaire,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, August 24, 1886: 1, and “Bellaire News,” Daily Register Wheeling, West Virginia), October 21, 1886: 1.

7 The Wheeling Register gave her name as “Blaney” in an announcement of the wedding on November 9, 1886 (“Bellaire,” 1), and it was also given as “Blaney” in other contemporary accounts (for example, “Pleasant Events,” Wheeling Sunday Register, July 19, 1885: 2, describing a gathering of young friends at the house of Miss Myrtle Robinson, which included “Lizzie Blaney” and “Thos. Nicholson.” In census records and on her Find-A-Grave website, her maiden name is “Blamey.” She was born in Wales around 1862 or 1863 and came to the United States in 1865 with parents and siblings, first to Pennsylvania and then to Bellaire by 1868.

8 “Diamond Dust,” Wheeling Intelligencer, May 14, 1887: 1, quoting the Bellaire Independent.

9 “A New Manager,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 6, 1887: 1.

10 The Wheeling Register noted on July 2, 1887 that the Wheeling team was “strengthened by the addition of Nicholson and Smurthwaite of the lately disbanded Steubenville team and Sol White of Bellaire.” In his first season in professional baseball, at the age of 19, White hit .370 for Wheeling in 53 games. He would go on to become a player and manager for Negro clubs for more than 30 years, with his final year as a player coming in 1911. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006 for his contributions to baseball.

11 Wheeling Intelligencer, September 28, 1887: 4

12 “The Young Blood Idea,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 11, 1888: 21. This article provides an introduction to a lot of the new players on the St. Louis Browns and St. Louis Whites for 1888.

13 Von der Ahe controlled the club and put up $5,000, while Tom Loftus and Charlie Comiskey each contributed $2,500, per “Scraps of Sport,” St. Paul Globe, October 29, 1887: 4.

14 “Wikoff’s Bulletin,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 13, 1888. The bulletin from the office of American Association Secretary Wikoff reports Nicholson’s release by the Browns without noting he was signed by the Whites, despite the fact that he had been playing in official games for the Whites for two weeks. The Wheeling Intelligencer reported (incorrectly) two days later that Nicholson was going to sign with Wheeling soon, “The delay was caused by the time some Association clubs took to consider whether they would agree to St. Louis releasing him” (“Notes from the diamond,” May 15, 1888: 4). Under the Association rules at the time, players released from one Association club had to be offered to the other clubs before that player could be sold or traded outside the league. This rule prevented the Browns from freely shifting players from the Browns to the Whites, and it helped contribute to the demise of the Whites in June when they were unable to place Jim Devlin on the club to replenish the roster following the sale of Jake Beckley and Harry Staley from the Whites to Pittsburgh.

15 “Tom Nicholson to Detroit,” Wheeling Intelligencer, September 13, 1888: 4.

16 Game details from the writeup in the Detroit Free Press, September 15, 1888: 8. The first portion of the article discusses the attempts of a fan, “M. J. Kelly, who is quite well known in base ball, theatrical and literary circles,” to help the visiting Quakers (also referred to as the Phillies in the article) by whistling to indicate whether the incoming pitch was straight or a curve, based on his deciphering the signals of the Detroit battery.

17 “Survived the Ninth,” Detroit Free Press, September 15, 1888: 8.

18 “Detroits, 7; Philadelphias, 5,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 15, 1888: 7.

19 Per Baseball Reference Home Run Log for Parson Nicholson.

20 “The Official Averages,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 12, 1889: 6.

21 Brooklyn folded in-season, and Baltimore returned from the Atlantic Association to complete the schedule.

22 “Bellaire,” Wheeling Intelligencer, January 29, 1892: 3.

23 “Baseball,” Detroit Free Press, January 2, 1895: 2.

24 “Base Ball Notes,” Evening Star, May 18, 1895: 13. The Detroit Free Press reported that “Washington tried [Nicholson] at short, but he did not like the position and after several days’ negotiation, Detroit secured him” (“Detroit Has Signed Parson Nicholson,” May 12, 1895: 6). Ironically, Scheibeck ended up not playing much for Detroit in 1895 due to an injury.

25 Statistics from the 1896 season are from Spalding’s 1897 Baseball Guide. The summary of the Western League season of 1896 runs from page 110 to page 114.

26 “The National Game,” Detroit Free Press, July 27, 1897: 6. They missed Grand Rapids, for whom Nicholson had also not played.

27 “Blues Make a Triple Play. Parson Nicholson is responsible for the great feat,” Kansas City Times, September 10, 1897: 2.

28 “Parson for Mayor,” Wheeling Intelligencer, February 8, 1898: 3.

29 “Changes in Manning’s Team,” Kansas City Times, May 11, 1898: 2.

30 “Bellaire,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, June 7, 1898: 2. A box score for the previous day’s game between Zanesville and Wheeling, with Nicholson at second base for Zanesville, is on page three of the same paper.

31 “Down Like a Stick,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, June 10, 1898: 3.

32 “Baseball Gossip,” Detroit Free Press, March 19, 1899: 8. In fact he hadn’t yet signed; his signing was contingent on whether Ed Mazena was able to be signed. See “More players coming,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, April 21, 1899: 3. Mazena and Mike Woodlock were unsigned due to a dispute with Syracuse over who had rights to the players. Both players had played with Springfield in 1898, and their rights transferred with the club to Wheeling for 1889. But Lew Whistler, manager of Springfield in 1898, signed the pair for Syracuse. The matter went to arbitration, and the pair were awarded to Wheeling in early May. Neither, however, ever played in Wheeling, although both played in Syracuse in 1899. Nicholson still never signed with Wheeling.

33 “General Sporting Notes,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News, July 7, 1899: 3.

34 “Club Changes Hands,” Wheeling Intelligencer, August 14, 1899: 3.

35 Statistics from the 1900 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 79.

36 “Bellaire Happenings,” Wheeling Intelligencer, February 23, 1900: 3, and April 20, 1900: 3.

37 “Sporting,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 26, 1899: 3.

38 “Base Ball Comment,” Wheeling Intelligencer, August 15, 1899: 3.

Full Name

Thomas Clark Nicholson

Born

April 14, 1863 at Blaine, OH (USA)

Died

February 28, 1917 at Bellaire, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.