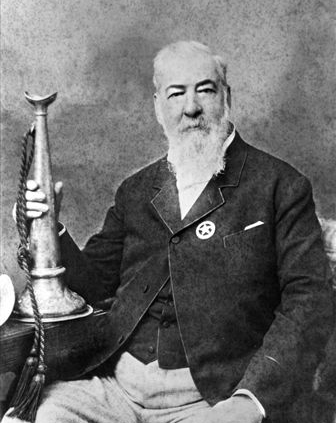

Alexander Cartwright

Other than Abner Doubleday, perhaps no person associated with the beginnings of baseball is more celebrated yet disputed than Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr. No evidence exists for Abner Doubleday’s having anything to do with baseball. There is, on the other hand, sufficient evidence to connect Cartwright with baseball. However, in light of interviews with other former New York Knickerbockers — Daniel Adams, Duncan Curry, and William Wheaton — uncovered in recent years, Cartwright’s alleged pivotal role has been questioned.

Other than Abner Doubleday, perhaps no person associated with the beginnings of baseball is more celebrated yet disputed than Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr. No evidence exists for Abner Doubleday’s having anything to do with baseball. There is, on the other hand, sufficient evidence to connect Cartwright with baseball. However, in light of interviews with other former New York Knickerbockers — Daniel Adams, Duncan Curry, and William Wheaton — uncovered in recent years, Cartwright’s alleged pivotal role has been questioned.

Randall Brown speaks about these men and the controversy over who has true claim to significant rule changes. For example, William Wheaton in an interview in 1887 laid claim to at least two particular rule revisions formerly attributed to Cartwright: the diamond configuration of the playing field and abolishing the rule of throwing the ball at the runner, ordering instead that it should be thrown to the baseman instead to achieve an out.

Joel Zoss and John Bowman address “The Cartwright Myth,” comparing various aspects of the game attributed to Cartwright to actual evidence in existence or the lack thereof. One such myth is that Cartwright umpired the first match game on June 19, 1846. The score sheets from that particular game are missing from the original Knickerbocker record books in the New York Public Library. Fortunately, those pages were photographed for a book by James M. Kahn, The Umpire Story, published in 1953. However, the umpire’s signature line is blank. Cartwright did not sign the umpire’s signature line, nor was he in the line up for the game. For the “extra play” that day, “J. Paulding” signed the umpire’s signature line, and Cartwright was not in the line up for that game either.

Born in New York City on April 17, 1820, to Alexander Joy Cartwright Sr., a merchant sea captain, and his wife Esther Burlock Cartwright, Alex Jr. was one of seven children. His six siblings were Benjamin, Katherine, Alfred, Esther, Mary, and Ann. Alex married Eliza Van Wie of Albany on June 2, 1842. Three children were born to them: DeWitt (May 3, 1843, in New York), Mary (June 1, 1845, in New York), and Catherine (or Kathleen) Lee — who was known as “Kate Lee” (October 5, 1849, in New York during Cartwright’s venture to California and Hawaii).

Cartwright began work in 1836 as a clerk at the age of sixteen in Coit & Cochrane, a broker’s office on Wall Street. He later earned his living as a clerk for Union Bank of New York. Banker’s hours permitted bank employees the opportunity to spend more time outdoors before heading home by nightfall. Accordingly, it was common during the early part of the nineteenth century in New York to see men gathering in the street or vacant lots for a game of ball after their work was done for the day. One such vacant lot was on 27th Street and 4th Avenue (Madison Square at the time) and later at 34th Street and Lexington Avenue (Murray Hill).

Many of these ball-playing young men, including Cartwright, were also volunteer firemen. The first firehouse that Cartwright was associated with was Oceana Hose Company No. 36. Later, he joined Knickerbocker Engine Company No. 12, located at Pearl and Cherry Streets. It disbanded in 1843. Some speculate that the young ballplayers, possibly Cartwright himself, named their ball club after the engine company, apparently sometime between 1842 and 1845.

A huge fire in July 1845 destroyed the Union Bank where Cartwright was employed. Consequently, Alex went into the book-selling business with his brother Alfred on Wall Street. They did not give up on their ball playing, though. Meanwhile, the city was growing and changing all around them.

The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club ventured across the Hudson River by ferry to Hoboken, New Jersey. There they found a roomy spot called Elysian Fields. The team drew up a constitution and bylaws on September 23, 1845, and twenty rules in all were adopted. The Knickerbocker rules are also synonymously known as the “Cartwright Rules.” Yet, there is no known documented physical evidence that substantiates this claim. Some of the rules attributed to Alexander Cartwright are: (1) a runner being touched with a ball, rather than hit with it to be considered out; (2) a ball being determined foul if outside the range of first or third base; and (3) one of the most debated of the “Cartwright rules,” the distance between the bases (paced out in a diamond-shaped format with forty-two paces from home to second base, and forty-two paces from first to third base).

Cartwright and his friends played their first recorded game on October 6, 1845, and continued playing well into late autumn that year. Receipts exist for dinners that are dated December 5, 1845, and are labeled with “Elysian Fields Hoboken for twenty dinners at $1.50 each for the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club.”

The first match game was played between the Knickerbockers and the New York Club on June 19, 1846, at Elysian Fields. The New York Club won 23-1. They were playing with what is claimed to be another one of Cartwright’s original rules, which is the first team to reach 21 aces or runs would win.

Documentation of Cartwright’s doings between June 1846 and March 1849 is scarce. He undoubtedly worked at his stationery and book store with his brother Alfred on Wall Street, volunteered in fighting fires when emergencies arose, spent time with his wife Eliza and two children, DeWitt and Mary, and kept playing base ball with the Knickerbockers.

Gold was discovered in California during January of 1848. News reached New York by September of that year. By March 1849, Alexander was off to California for adventure and hopes of striking it rich — unaware that he and Eliza had their third child on the way.

What is alleged to be the original handwritten diary of that journey, or a portion of it, resides in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Alexander’s grandson, Bruce Cartwright Jr., typed a transcribed copy of it as late as the 1930s. In that copy Alexander is described leaving New York on March 1, 1849, to travel by train to St. Louis. From St. Louis he took a steamboat to Independence, Missouri. According to the typed transcription of the journal, A.J. Cartwright Jr. wrote on April 23, 1849: “During the past week we have passed the time in fixing the wagon-covers, stowing away property etc. varied by hunting and fishing, swimming and playing Base-ball. I have the ball and book of rules with me that we used back home.”

An undated passage that begins the handwritten journal in the Bishop Museum states: “Left Independence and traveled to the Boundary line, where we camped with Colonel Russell’s Co. for over a week nothing of note occurring, time passed in “fixing” waggon [sic] covers, stowing away property &c [sic] varied by hunting, fishing, and swimming.”

No mention of baseball at all is in the handwritten version. The handwriting of this journal was analyzed by certified document examiner Reed Hayes of Honolulu. After comparing several known handwriting samples of Alexander Cartwright Jr. to the handwriting of the Bishop Museum journal, Reed Hayes determined that Cartwright did not author the journal. DeSoto Brown, archivist and collections manager at the Bishop Museum, states that handwritten items of high importance to families were sometimes transcribed by someone with excellent handwriting. Scribes were sometimes hired in nineteenth century Honolulu to transcribe important documents. Even if this were the case for the alleged Cartwright Gold Rush journal, why would anything to do with baseball be left out if it was in the original writings?

Bruce Cartwright Jr. typed two journal transcriptions for family genealogy purposes. In one of those transcriptions he reveals that the original diary was burned in 1893 and he “completed the narrative drawn from all available sources…” One of these transcriptions has A.J.C. departing on his journey on April 23rd, and playing baseball prior to departure. Bruce states that the surviving “notes” with original information by his grandfather are owned by his cousin Mary. However, according to records at the Bishop Museum, it was Bruce’s cousin “Mary” who bequeathed her grandfather’s journal to the museum and stated that it was the “original.”

To further question the claims of Cartwright playing and teaching baseball everywhere he went across the plains, one need only read the two other known diaries written by men who accompanied Cartwright out West in 1849. Louis. J. Rasmussen’s research of Wagon Train Lists documents men who accompanied Cartwright in the same overland company. This information is corroborated by newspaper accounts. The only existing diaries are of Charles Gray and Cyrus Currier, in which no baseball is mentioned. Yet neither is Cartwright. Unfortunately, no other diaries have surfaced from those who were with the Newark Overland Company.

When Cartwright reached California he did not stay long, sailing for Hawaii on August 15, 1849. Upon arrival in Honolulu, Alex Cartwright must have inhaled the fragrance of tropical flowers — plumeria, jasmine, and gardenia — along with the sweet smell of pineapple and sugar cane in the air. In Honolulu, Cartwright met up with former New York acquaintance Aaron B. Howe, who owned a ship chandler’s business, and entered Howe’s employ as a bookkeeper.

Ancient Hawaiians revered Pele, the Goddess of Fire, but nineteenth-century Hawaiian society had to fight fire with buckets of water. W.C. Parke formed Honolulu’s first Volunteer Fire Brigade in November of 1850 and not a day too soon, for that day a fire broke out and eleven homes were destroyed. Parke was Honolulu’s first fire chief from that moment, but for unknown reasons, on December 27, 1850, King Kamehameha III passed an act in Privy Council that appointed Cartwright Chief Engineer of the Fire Department of the City of Honolulu. Oahu’s Governor, Kekuanaoa, signed the act on February 3, 1851. Kamehameha reportedly took an immense interest in the department. When the alarm went off, the reigning monarch shed his coat, rolled up his sleeves and helped right alongside the other volunteers.

A passenger list dated November 13, 1851, for the American ship Eliza Warwick shows Mrs. Cartwright and her three children, DeWitt, Mary, and Kathleen, traveling to Honolulu from San Francisco. An elaborate gravestone in the Cartwright cemetery plot in Honolulu shows that “Kate Lee” died in Honolulu on November 16, 1851. The other two Cartwright children also died young. Mary Cartwright Maitland died in 1869 at age 24, nearly three years after she married, and had no children. DeWitt died in 1870 at age 26. He was not married and had no children.

Two more children were born to Alexander and Eliza in Honolulu, Bruce in 1853 and Alexander III in 1855. Bruce grew up in Honolulu, married and had children, Bruce Jr. and Kathleen DeWitt. Alexander III married Theresa Owana Laanui and had two daughters — Daisy Napulahaokalani and Eva Kuwailanimamao. They divorced, and he eventually moved to San Francisco and married Susan Florence McDonald. They had two daughters — Ruth Joy and Mary Muriel. Mary Muriel married Elliott Everett Check. It was through Mary that her grandfather’s Gold Rush diary was donated to the Bishop Museum in Honolulu from her estate.

Bruce Jr.’s lineage can be traced to having three children, two of whom died quite young (Bruce III and Coleman), and another, William, who married Margery and had one daughter Jane. William and Margery divorced, and William later married Anne and had two more children, daughter Anna and son Alexander J. Cartwright IV. It was Bruce Jr. who first wrote to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936 about his grandfather and baseball.

Aside from his duties at the Honolulu Fire Department, Alexander became involved with many other aspects of the city through his involvement with Freemasonry. In 1859, for example, Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV founded Queen’s Hospital. As part of its customs and traditions, cornerstone ceremonies were held for the construction of new buildings. The first public Masonic ceremony on the islands was at the laying of the hospital cornerstone in 1860.

As an advisor to the queen, Cartwright was the executor of her Last Will & Testament, in which she left the bulk of her estate to the hospital when she died in 1885. He also was appointed Consul to Peru, and was on the financial committee for Honolulu’s Centennial Celebration of American Independence held on July 4, 1876.

A group of men, Cartwright among them, founded the Honolulu Library and Reading Room in 1879. The sponsors had originally named it the “Workingmen’s Library,” but felt that it needed a broader name to signify its true concept. In the local newspaper, the Commercial Pacific Advertiser, editor J. H. Black wrote, “The library is not intended to be run for the benefit of any class, party, nationality, or sect.”

Some of the founders wanted to exclude women from membership, but Cartwright disagreed, writing to his brother Alfred: “The idea keeps the blessed ladies out and the children. What makes us old geezers think we are the only ones to be spiritually and morally uplifted by a public library in this city?” It wasn’t long before the committee changed the wording of the constitution to make women eligible for membership.

Alexander Cartwright was involved with the library for the rest of his life, and was president from 1886 to 1892. The Reading Room librarian, Mary Burbank, said “Mr. Cartwright’s name led the list of the first Board of Directors in 1879, and [he] remained on the board as long as he lived, giving the most generously of books.” Cartwright was a constant reader, frequently donating his own purchased books after he had read them.

Another little known fact is that Cartwright was one of twelve men who belonged to a “birthday club.” Beginning in December of 1871, the twelve men would have a “first-class” dinner at one of the members’ homes each month. The honorary president was King Kamehameha V. Their last dinner would be on May 2, 1872. The king suffered an attack of dropsy and died on December 11 (his 42nd birthday). Once the king fell ill, the club postponed their dinners, and never met again.

King Kamehameha V was the first native Hawaiian to become a Freemason. The February before he died, a cornerstone was laid in Masonic tradition with members of the lodge present, including the Acting Grand Master, Alexander Cartwright Jr. The king, together with Cartwright, spread cement beneath the Cornerstone for what would become the Judiciary Building.

The next monarch, King Kalakaua, became the first Hawaiian monarch to attend a baseball game. Cartwright was the king’s financial advisor. The game took place in 1875 between the Athletes and the Pensacolas. Baseball had been growing in popularity since being played at Punahou School in the 1860s. But it is unclear whether Cartwright actually instituted the playing of the game on the islands.

Spalding‘s world tour of 1888-89 brought the Chicago White Stockings and the All-American teams to Honolulu in November of 1888. They were due to arrive on a Saturday and play a scheduled game at 1:00 PM. Unfortunately, their ship didn’t arrive until 5:30 Sunday morning. Some political aspects to their visit prevented them from playing a game on a Sunday. The “blue law,” originally created by New England missionaries in 1820, was enforced by the missionaries’ descendents in defiance of the king, as political powers were plotting to overthrow the monarchy.

Cartwright is not mentioned in any newspaper article or historical documents as to his involvement or even being in attendance when Spalding’s group arrived in Honolulu. In America’s National Game (1911), Spalding states that Cartwright was “one of the devotees of Base Ball…” To some this statement appears as though Spalding and Cartwright met and spoke with one another. However, further research points to the fact that Bruce Cartwright Jr. wrote Spalding about his grandfather’s baseball beginnings.

While Spalding was in Honolulu for his brief, one day stay, he seemed impressed by remarking that Honolulu had four established clubs and that baseball was fully appreciated there. There is recorded evidence that Cartwright’s Hawaiian-born sons, Bruce and Alex III, played baseball between the 1860s and 1880s in Honolulu. Without a doubt these young men, standing right beside their father, would not have missed seeing the professional ball players come to town. Yet, no record exists to substantiate this. Given Cartwright’s personal connection to the monarchy, it is also feasible that the Cartwright family attended a grand luau held at the queen’s home to honor the visitors on Sunday evening. However, no record exists of Cartwright’s attendance at this event either.

Alexander Cartwright died on July 12, 1892, apparently of an infection from a boil on his neck.

The Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown six months later on January 17, 1893. A group of Americans in Honolulu formed to request of President Benjamin Harrison that Hawaii be annexed to the United States. The president was in favor. The individual leading the cause for annexation was Lorrin Thurston. Coincidentally, Thurston had played baseball at Punahou School at the same time as Alexander III and Bruce Cartwright Sr.

Decades later, Alexander Cartwright’s grandson Bruce Jr. was earnest in getting recognition for his grandfather by writing letters to Cooperstown, New York, where the National Baseball Hall of Fame was being built. Bruce Jr. wrote a letter to Arthur Alexander in 1938 referring to a letter written by his grandfather to Charles DeBost (1865) stating that he had in his “possession the original ball with which we used to play on Murray Hill. Many is the pleasant chase I have had after it on Mountain and Prairie…” Bruce used the DeBost letter as his main documented source for his grandfather’s involvement with baseball. Alexander Cartwright was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1938 in a “pioneers” category for the Veterans’ Committee ballot.

The fact that the National Baseball Hall of Fame was being built in Cooperstown where supposedly Abner Doubleday introduced the game as a boy in 1839 was not sitting well with reporters and researchers whose investigations proved otherwise. Some speculation exists that Cartwright was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame as a means of deflecting the growing controversy over Abner Doubleday. To this day, Doubleday has not been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Three months before the official opening ceremonies of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Bruce Cartwright died on March 11, 1939. Later that year the grand opening celebrations for the Hall of Fame were held in Cooperstown and the festivities extended to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. August 26, 1939, was “National Cartwright Day.” Ballplayers at Ebbets Field drank pineapple juice in a toast to Cartwright. It was the first major league baseball game broadcast on television. After all the celebrations passed into history and the site for exhibiting the triumphs of baseball became well-known, baseball researchers and historians continued to question “fact” and debunk myth.

One of the most misleading tributes to Cartwright’s contribution to baseball is the wording on his Hall of Fame plaque. Aside from being declared as “The Father of Modern Baseball,” the plaque lists three rules of the game attributed to Cartwright: “Set Bases 90 Feet Apart; Established 9 Innings as Game; and, 9 Players as Team.”

In actuality, those particular Knickerbocker rules are stated in this manner: “The bases shall be from home to second base, forty-two paces; from first to third base, forty-two paces, equidistant”; “The game to consist of twenty-one counts, or aces; but at the conclusion an equal number of hands must be played”; and, “If there should not be a sufficient number of members of the Club present at the time agreed upon to commence exercise, gentlemen not members may be chosen in to make up the match, which shall not be broken up to take in members that may afterwards appear; but in all cases, members shall have the preference, when present, at the making of a match.”

We don’t know why the committee for the Hall of Fame chose these three rules and their wording for Cartwright’s plaque. But we do know that the fullness of his contribution to the game’s origins remains one of baseball’s greatest mysteries.

In Honolulu, Hawaii, Alexander Cartwright is a well-known historical figure. A large pink granite monument in Oahu Cemetery (formerly Nuuanu Valley Cemetery) in Honolulu marks his final resting-place. Many baseball personalities, including Babe Ruth, have visited this spot to pay tribute. Today, baseballs and notes can be found lying at the foot of his large grave marker, especially around the time of his birthday every April. A street and a park nearby were named after Cartwright. The park was originally called Makiki Park, where it was known as the first grounds used for playing baseball. Oral history handed down from Bruce Cartwright Jr. is that his grandfather paced out the diamond at Makiki Park, now named Cartwright Park in Honolulu. As he told a journalist for an article in the magazine Paradise of the Pacific, “When I was a small boy it was my great joy to hear grandpa tell about the early days of baseball in New York and his adventures while crossing the continent.”

Bruce Jr. was ten years old when his grandfather died. Could it be that while Bruce Cartwright Jr. was a young boy that his memories were colored by a child’s adoration of his grandfather? Especially interesting would be hearing stories from a grandfather who talked about crossing the Wild West in search of gold and of playing a game that was played by boys and young men in the far away metropolis of Manhattan in New York.

Within Cartwright’s obituary, published in both the Hawaiian Gazette and Pacific Commercial Advertiser in July 1892, baseball was not mentioned as one of his life’s passions or undertakings. Nevertheless, Cartwright’s life was seen as full and accomplished, as indicated in the beginning of his obituary: “To publish more than an epitome of the eventful life of A. J. Cartwright is not practicable in a work of this character. He was one of the early Argonauts of California, and his biography would, if exhaustively written, be extremely interesting. It would indeed fill a volume, and be an invaluable text book to place in the hands of the rising generation to reflect upon and emulate.”

The controversy over Cartwright continues to this day. Whether it is “Cartwright Rules” or “Knickerbocker Rules,” the rules of baseball are ever-changing. And so are the research findings where Cartwright’s role in baseball history is concerned. This short biography of Cartwright’s life is the second version since its first posting on SABR’s Biography Project website, and there will undoubtedly be additional versions posted as the years pass into history.

Note

In 2009, the author completed work on a book on Alexander Cartwright, published by the University of Nebraska Press. For more information, please visit the book’s website.

Sources

Ardolino, Frank. “Missionaries, Cartwright, and Spalding: The Development of Baseball in Nineteenth-Century Hawaii.” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture 2 (Spring 2002), 27-45.

Brown, Randall. “How Baseball Began.” The National Pastime #24. (SABR, 2004), 51-54.

Cartwright collection. “Centennial Celebration of American Independence.” State Archives of Hawaii (1876)

“Cartwright Day, With Leis, on Television.” Hawaiian Gazette. (August 1939)

Cartwright family artifact. Passenger List of American Ship Eliza Warwick (1851).

Cartwright Lineage and Genealogy. Cartwright Family archives.

Cartwright Obituary. Hawaiian Gazette and Pacific Commercial Advertiser (July 19, 1892).

Cartwright, Alexander J. Jr. Gold Rush Diary. Bishop Museum (1849).

_____. Letter to Charles DeBost. Barry Halper Collection (1865).

Cartwright, Bruce Jr. “The Long Table of Kamehameha V.” Paradise of the Pacific (July 1913).

_____. Cartwright Diary Transcription. Cartwright Family archives.

City and County of Honolulu. Resolution (1938).

Email correspondence, Clark, Deputy Chief John. Honolulu Fire Department (2004).

Email correspondence, Stingone, William. New York Public Library (2006)

Erikson, Jerry R. “A Freemason was the Father of Baseball.” The Royal Arch Mason (Fall 1962).

Furukawa, S.F. “Originator of Organized Baseball.” Paradise of the Pacific (May 1947).

Kahn, James M. The Umpire Story. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1953.

Loomis, Albertine. “The Best of Friends.” Friends of the Library of Hawaii (1979).

Peterson, Harold. The Man Who Invented Baseball. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969.

Pitzer, Pat. “Overthrow of the Monarchy.” Spirit of Aloha (May 1994).

Rasmussen, Louis J. California Wagon Train List. San Francisco Historic Records, 1994.

Vlasich, James A. A Legend for the Legendary: The Origin of the Baseball Hall of Fame. Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1990.

Zoss, Joel, and John Bowman. Diamonds in the Rough: the Untold History of Baseball. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc, 1996.

Special thanks to Tom Shieber of National Baseball Hall of Fame; Reed Hayes of Hawaii, Nanette Napoleon of Hawaii, DeSoto Brown of Bishop Museum, Barbara Dunn of Hawaiian Historical Society, John Thorn of New York, and Angus MacFarlane of California for their research assistance.

Additional gratitude goes to Fred Ivor-Campbell of SABR for his editing expertise.

Full Name

Alexander Joy Cartwright

Born

April 17, 1820 at New York, NY (US)

Died

July 12, 1892 at Honolulu, HI (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.