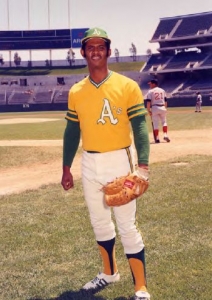

Angel Mangual

On a team composed of several leading men and future Hall of Famers, Ángel Mangual was, at most, a minor actor in a supporting role on the great Oakland A’s teams of the early 1970s, good for an occasional walk-on or cameo appearance. He was dubbed the “Little Clemente,” but it was a billing he never lived up to. In recent years, one less-than-empathetic baseball blogger has opined, “I can think of no outfielder on any other dynastic team who was given so much playing time over such an extended period of time with such poor production.”1 It was a harsh but mostly accurate assessment; he could have also mentioned Mangual’s erratic play in the outfield. But for one night in the fall of 1972, the spotlight shone brightly on the quiet 24-year-old outfielder from Puerto Rico. Headlines across the country blared out the following day: “Mangual Gets Winning Hit,” “’Little Clemente’ Puts A’s One Game Away,” “Athletics on the Wings of an Angel,” and “Mangual Takes After Clemente.” It would prove to be his moment in the sun.

On a team composed of several leading men and future Hall of Famers, Ángel Mangual was, at most, a minor actor in a supporting role on the great Oakland A’s teams of the early 1970s, good for an occasional walk-on or cameo appearance. He was dubbed the “Little Clemente,” but it was a billing he never lived up to. In recent years, one less-than-empathetic baseball blogger has opined, “I can think of no outfielder on any other dynastic team who was given so much playing time over such an extended period of time with such poor production.”1 It was a harsh but mostly accurate assessment; he could have also mentioned Mangual’s erratic play in the outfield. But for one night in the fall of 1972, the spotlight shone brightly on the quiet 24-year-old outfielder from Puerto Rico. Headlines across the country blared out the following day: “Mangual Gets Winning Hit,” “’Little Clemente’ Puts A’s One Game Away,” “Athletics on the Wings of an Angel,” and “Mangual Takes After Clemente.” It would prove to be his moment in the sun.

With Oakland losing 2-1 to the Cincinnati Reds in the bottom of the ninth inning in the pivotal fourth game of the 1972 World Series, the A’s mounted a last-ditch rally before an ecstatic crowd of 49,410 at the Oakland Coliseum. It proved to be a comeback for the ages. After left-handed-hitting first baseman Mike Hegan opened the frame off Reds reliever Pedro Borbón with a hard-hit groundout to third, A’s manager Dick Williams leaned heavily on his bench. Gonzalo Marquez, a superb situational left-handed hitter, bounced one up the middle (he went 5-for-8 in postseason pinch-hitting roles that fall), bringing the partisan crowd to its feet. Reds manager Sparky Anderson then pulled some levers of his own. With a 2-and-1 count on A’s catcher Gene Tenace and the tying run on first base, Anderson yanked Borbón in favor of his best reliever, Clay Carroll, who had set a major-league record with 37 saves during the season. The A’s hadn’t touched him in any of his previous appearances in the fall classic.

Tenace, who had homered earlier in the game for his third round-tripper of the Series, slapped Carroll’s second offering solidly into left field, sending controversial pinch-runner Allan Lewis, the “Panamanian Express,” to second. Then pinch-hitter Don Mincher, the A’s aging backup first baseman, roped a line-drive single into right-center field, scoring Lewis to tie the game and sending Tenace to third. The crowd went wild — the noise, according to one account, was “ear splitting”2 — and the stage was set for yet another A’s pinch-hitter, this time the right-handed-hitting Mangual. Williams pulled the final card from his sleeve, sending Blue Moon Odom in to pinch-run for the slow-moving Mincher.

Sparky Anderson might have had Carroll walk Mangual to load the bases and set up a possible double play. But the A’s next batter was Campy Campaneris, a tough hitter to double up, and in Anderson’s mind, he would later say, simply a tougher out.3 Anderson directed Carroll to go after Mangual, who had hit only .246 with five home runs during the regular season. It was his first at-bat of the Series. Anderson’s strategy backfired. With the infield playing in, Mangual, executing an inside-out swing, punched Carroll’s first pitch — a fastball over the inside portion of the plate — beyond the reach of the Reds’ second baseman Joe Morgan for a game-winning single, scoring Tenace, as Mangual was mobbed by his teammates after reaching first base.

It was the first time in World Series history that a team had collected three pinch hits in an inning. Williams, who had also used two pinch-runners in the bottom of the ninth, looked like a genius. “When I hit the ball,” Mangual said after the game, “the first thing that came to mind was that it was a double-play ball. I know I got to run. I wouldn’t even look at the ball. I just put my head down and prayed that it would go through.”4

The underdog A’s, scoring only 16 runs in seven games, went on to win the Series, the first for the franchise since Connie Mack led the Philadelphia Athletics to a world championship over the St. Louis Cardinals in 1930. And Mangual’s heroics would mark the high point of his less-than-fabled career.

Ángel Luis “Cuqui” Mangual Guilbe was born on March 19, 1947, in Juana Díaz, Puerto Rico, a sugar-cane center on the south coast of the island. He grew up in a family that worshipped baseball and the national idol, Roberto Clemente. Mangual’s younger brother, José “Pepe” Mangual, and his older cousin, José “Coco” Laboy, also played major-league ball.

The 19-year-old Mangual was signed in 1966 by the Pittsburgh Pirates’ legendary Puerto Rican scout, Francisco “Pancho” Coímbre, who had also persuaded the Pirates to draft Clemente. Mangual played his first professional season with the Clinton Pilots of the Class A Midwest League, batting a meager .228 in 80 games, with only four home runs. But he also got his first professional attention that season. An article in the Muscatine (Iowa) Journal in June noted that Mangual had hit a pinch-hit home run for the Pilots, in the same article that highlighted a young Graig Nettles for hitting a three-run home run for the Wisconsin Rapids Twins.

The following year, with Raleigh of the Carolina League (Class A), Mangual upped his average to .285, collecting 150 hits in 136 games; his defense, however, was terrible. He made 17 errors in the outfield for a dismal fielding percentage of .940.

The 5-foot-10 Mangual worked his way slowly through the Pirates’ farm system. At York in the Double-A Eastern League in 1968, he batted a lackluster .249, but his fielding percentage improved to .981.

In 1969, at the age of 22, Mangual staged a breakout season at York. By midseason he was leading the league in hits, batting average, doubles, total bases, and RBIs. He wound up finishing second in the batting race with a .320 average, but led the league with 26 home runs and 102 RBIs in only 133 games. His stellar performance earned him honors as both Player of the Year and Most Valuable Player in the Eastern League, as well as a coveted end-of-the season call-up to the Pirates’ Triple-A affiliate, the Columbus Jets, and then to the big-league Pirates, where he collected a double in four at-bats, and got a chance, if only for a brief moment, to rub shoulders with his boyhood idol Clemente.

Pittsburgh area papers began to take notice of the rising young outfielder. “The fact that York of the Eastern League ran away with the pennant was due largely to the sensational hitting exploits of Angel Mangual, named Player of the Year and MVP of the Eastern league,” said one. “… (H)e has all the tools to develop into a major league star.”5

Mangual must have begun believing the press. He was a holdout at training camp the following February, signing the day before the Pirates’ 1970 spring training camp opened in Bradenton, Florida. He was the last Pirate on the team’s 40-man roster to sign. He was competing for the Pirates’ fourth outfield position, as a backup in center field to Matty Alou. Mangual actually told reporters that he didn’t want the job. “I want to go somewhere I can play every day,” he said.6 Alou had led the National League with 231 hits in 1969 and had batted .331. When camp broke, Mangual was sent to Triple-A Columbus. He was the last outfielder cut from the team.

Mangual held his own on the Jets in 1970, starting in right field and batting a respectable .281 with 20 home runs, though he didn’t receive a call-up to the Pirates at the end of the year. Instead, after the season the Pirates sent Mangual to the Oakland Athletics to complete a deal made on September 14, 1970, involving pitcher Mudcat Grant.

Mangual came to the A’s with high hopes. Charles Finley believed that A’s starting center fielder, Rick Monday, was “not going to be the star that everyone predicted”7 and that Mangual was the A’s center fielder of the future.

Many people forget how dominant a team the A’s were in 1971, winning 101 games in the American League West and finishing 16 games ahead of the second-place Kansas City Royals. Mangual hit the first home run of his major-league career on April 27, breaking up a shutout being pitched by left-hander Dave McNally. But he was off to a slow start. By May 18, Finley was offering up Mangual as part of a trade for Sam McDowell. It didn’t happen. Perhaps the rumor of a trade lit a fire under Mangual’s feet. In early July, in the longest scoreless game in American League history, Mangual singled with two outs against the California Angels in the bottom of the 20th inning to drive home the winning run in a 1-0 victory. Finley called the A’s clubhouse with “orders” for Mangual to go out and buy himself a $200 suit and charge it to Finley.8 Manager Dick Williams indicated that Mangual “may get more chances to play in the second half of the season.” At the time, Mangual was batting .322 against right-handed pitching, while Monday was batting just .229. “He’s earned it,” Williams said of Mangual.9

While Monday started most games in center field that season (batting a mediocre .241), Mangual wound up playing in 94 games (the most among A’s bench players), batting .286. His promising performance placed him third in the Rookie of the Year vote and second in The Sporting News balloting for top rookie. (Chris Chambliss of the Indians won both competitions.) He was named to the Topps All-Rookie team.

In a rare journalistic portrait of Mangual appearing in the April 1972 Baseball Digest — his limited English skills proved to be a barrier for sportswriters during that era — Steve Ames interviewed Clemente about his young countryman. “He has a quick bat,” the Great One noted. “But it’s a matter of confidence. He has the tools and he could be a hell of a ballplayer. Time will tell. It depends on his mind.”10

Clemente described Mangual as “a pretty nice kid; listens to everybody; good fellow, good family.” With Al Oliver and Willie Stargell coming up in the Pirates organization, Clemente called the trade to Oakland a stroke of good fortune for Mangual. “Look over our roster,” he said. “The best thing was a trade. It was a break for Angel.”

“I had played right field in the minors,” Mangual told Ames in the article. “I thought someday I’d play, you know, right field for the Pirates. I knew I could play, you know. But no position for me in Pittsburgh. I’m glad to be here; A’s give me a chance.”

Mangual also paid homage to his hero, Clemente: “Roberto was a big help to me, show me, you know, how to hit, how to play outfield. He talked to me all the time. He said when pitcher throws hard you open your hips. For breaking pitcher, try to hit the ball to right field.”

“I wish he don’t try to be a long-ball hitter,” Clemente interjected. “He got lots of power; not so much that he should try home runs.”

“It is a credit to Mangual,” writer Ames observed, “a scatter-shot hitter blessed with quick hands, that he is Mr. Relaxed prior to a game.…He may be seen walking around the clubhouse twisting a foot-long steel rod to strengthen his hands or lying on the rug signing baseballs or talking with another player. He’s good natured.”

“We had a very strong outfield situation last year,” A’s manager Williams declared, “and even though we traded away a good center fielder in Monday, we feel that Mangual earned the job as a regular with an outstanding season.”11

The experiment didn’t work out. Mangual’s defense was erratic; Reggie Jackson actually played 92 games in center field that year and only 43 in right. Mangual played 51 games in right field and 22 in center. He wound up collecting only 67 hits in 272 at-bats, scoring a mere 19 runs without a single stolen base. His celebrated pinch hit in Game Four of the Series was the highlight of an otherwise dismal year.

The following season, 1973, was no different. Finley kept Mangual on the roster, though he batted only .224 with three home runs. He also was a liability in the clubhouse. Midway through the season, Mangual got into a fight aboard an airplane flight with A’s pitcher Blue Moon Odom, a well-known music aficionado who was playing a cassette loudly. “Shut it off,” Mangual barked. “Hell no,” Odom retorted, charging Mangual. The two had to be separated by teammates.12

On another occasion, Mangual threw his helmet to the ground in disgust when manager Williams ordered Jackson to pinch-hit for him in a game in which Mangual had started. Williams fined him $200. “I wasn’t tossing my helmet because Reggie pinch-hit for me. I did it just to relax,” an uncontrite (and unconvincing) Mangual told The Sporting News. “If Williams no like me, why doesn’t he trade me?”13 But given both his attitude and poor performance on the field, the real question is what the A’s could get for their unhappy outfielder. Although they won the American League West again in convincing fashion, there would be no heroics for Mangual in postseason play this time to compensate for a subpar season. He batted .111 in the American League Championship Series against Baltimore and went hitless in six at-bats during the World Series against the Mets.

The 1974 season proved to be more of the same. Mangual started erratically in all three outfield positions, and also served as the A’s designated hitter in 37 games, batting a dismal .233 with only 9 home runs and 43 RBIs. During the playoffs he was reduced to an afterthought, collecting a single in four at-bats against Baltimore in the ALCS, and striking out in his only World Series at-bat against the Los Angeles Dodgers. Nonetheless, he collected his third World Series championship ring.

By 1975 the writing was on the wall. A sullen Mangual played in only 62 games during the regular season, collecting a mere 24 hits en route to a .220 average. His one highlight was winning the team bubble-gum blowing championship. The contests were sponsored by the Bazooka Gum Company and overseen by “gum commissioner” Joe Garagiola, but Mangual was replaced for the finals by Glenn Abbott. More significantly, he was left off the roster for the A’s ALCS encounter with the Boston Red Sox. In September he was placed on waivers to make room for César Tovar. “It’s just a necessity when you are going for all the marbles,” said Finley. “We felt that he was expendable. We just thought that Tovar could be of more help to us than Mangual.”14

The following year, Mangual broke spring training with the A’s Triple-A farm team in Tucson. He was called up to Oakland briefly in June, collecting a single and a double in a dozen at-bats, and his numbers in the Pacific Coast League weren’t much better. He batted .274 at Tucson in 42 games, with two home runs. A nerve injury in his neck had left one of his hands feeling numb. What little power he had was gone. He also lost several fly balls in the desert sun — one of his miscues cost a Toro teammate a no-hitter – and the A’s released him outright. As though adding insult to injury, both of his Toros baseball cards issued that season misspelled his last name as “Manguel.”

Mangual bounced around in the lower minor leagues for three more seasons — he played with the Aguascalientes Rieloeros and the Poza Rica Petroleros in the Mexican League, and later with the Puerto Rico Boricuas of the Inter-American League (batting a paltry .190 in a handful of games), but he never gained traction again as a player. His days in baseball were over — at the age of 32.15

For the next two decades, Mangual was off the radar of professional baseball, but in May of 1997 he made headlines again, this time of a different sort. According to several news accounts, Mangual “and 21 other alleged members of [a] drug ring [based in Puerto Rico], including a policeman and a prison guard, were taken into custody Monday by police officers and federal agents.” A federal indictment accused Mangual of acting as “an intermediary between drug-buyers and sellers.”16

Whether or not Mangual served time for his alleged activities is unknown. In August 2010, his personal 1972 world championship trophy, presented to all A’s players by Finley, was sold at auction. His last recorded public appearance was in January of 2013, when he participated in SABR Day, sponsored by SABR’s Orlando Cepeda Chapter at the Francisco “Pancho” Coimbre Sports Museum in Ponce, Puerto Rico, where he appeared with his cousin and former major leaguer José “Coco” Laboy.17

Mangual died on February 16, 2021 at the age of 73.

Last updated: February 16, 2021 (ghw)

Notes

1 Baseball-Fever.com. Thread: “70’s A’s —Angel Mangual,” May 2010.

2 Associated Press, Santa Cruz (California) Sentinel, October 20, 1972, 19.

3 Raleigh Register, Beckley, West Virginia, October 20, 1972, 8. Anderson’s exact quote was: “I’d rather pitch to Mangual than to Bert Campaneris, who was up next. I thought we could handle Mangual.”

4 Pittsburgh Press, October 20, 1972, 29.

5 “Twelve Pirate Hopefuls Named Minor League All-Stars,” Uniontown (Pennsylvania) Evening Standard, February 9, 1970, 19.

6 “Pirates to Open Friday,” Simpson’s Leader-Times (Kittanning, Pennsylvania), March 5, 1970, 14.

7 Mark L. Armour and Daniel R. Levitt, Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books Inc.: 2004), 253.

8 Kentucky New Era (Hopkinsville, Kentucky, July 2, 1971, 12.

9 “Williams Promises Mangual More Work,” San Mateo (California) Times, July 10, 1971, 6.

10 Steve Ames, “Mangual of the A’s: An Angel with a Quick Bat,” Baseball Digest, April 1972, 35-36. I have quoted Ames’ article verbatim. He invokes a typical journalistic practice of the times, that of quoting Spanish-speaking players from Latin America in broken English rather in their native Spanish. It tended to make them sound illiterate. As such, it is important to understand Mangual’s career in a larger framework that addresses the various ways in which Latino ballplayers at all levels of professional baseball were subjected to the racist and ethnic stereotypes of their times. See Adrian Burgos, Jr., Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos and the Color Line (Berkeley: University of California Press: 2007).

11 Ibid.

12 Hope (Arkansas) Star, July 13, 1974, 6.

13 Cited in “Cooperstown Confidential” Regular Season Edition, by Bruce Markham, Oaklandfans.com, June 12, 2003.

14 Kansas City Star, September 1, 1975, 9.

15 Mangual’s statistics from playing in Puerto Rico’s winter league are not available online.

16 Toledo Blade, May 7, 1997, 3.

17 According to Luis Machuca, president of the Orlando Cepeda SABR Chapter (Puerto Rico), Mangual as of 2014 resided in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Efforts to contact him via telephone for this profile proved unsuccessful.

Full Name

Angel Luis Mangual Guilbe

Born

March 19, 1947 at Juana Diaz, (P.R.)

Died

February 16, 2021 at Ponce, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.