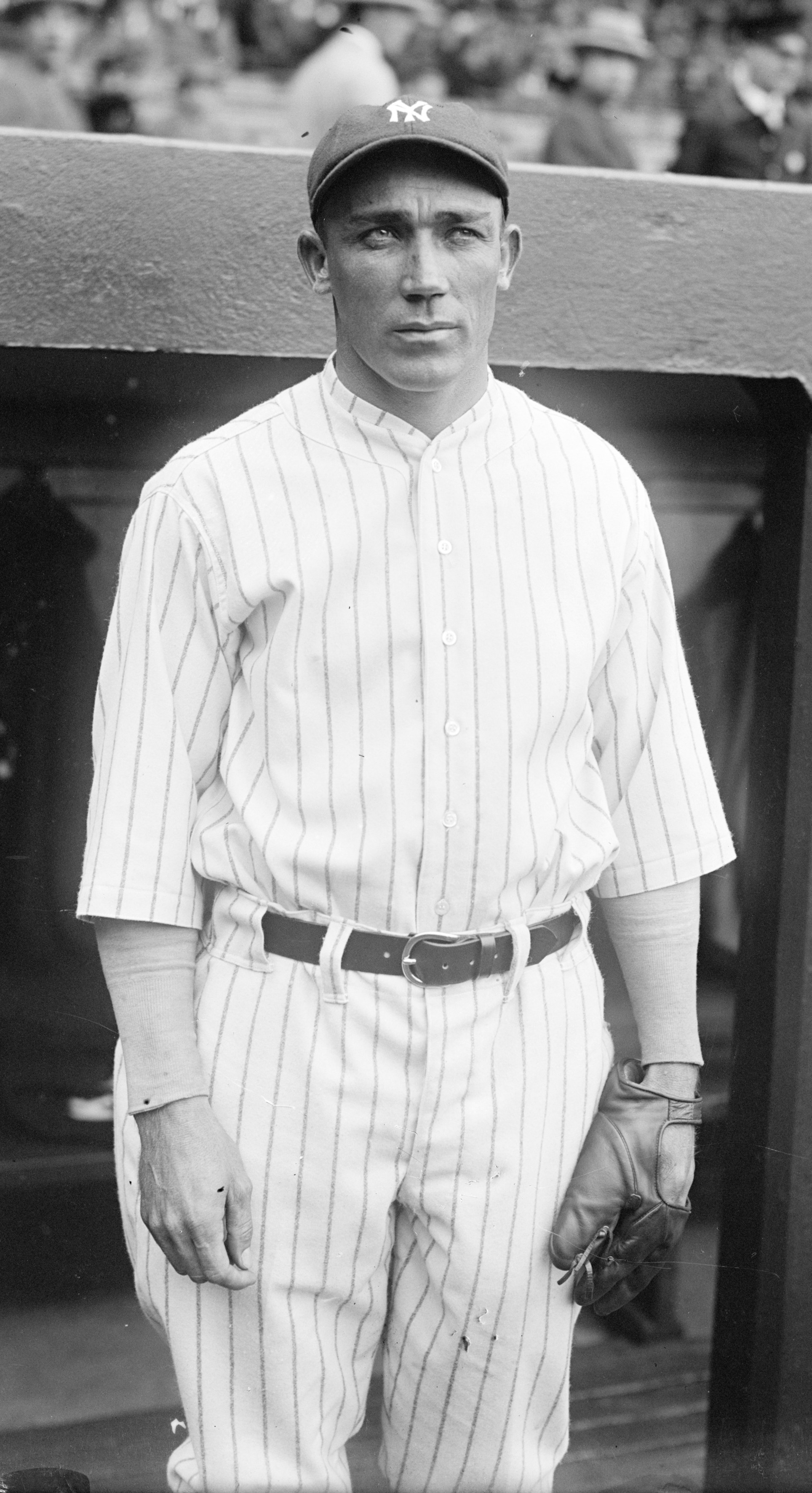

Ben Paschal

“Ben was a fine hitter. He could have starred on any team in the major [leagues] except the Yankees. He wound up playing behind Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel in the Yankee outfield.”

“Ben was a fine hitter. He could have starred on any team in the major [leagues] except the Yankees. He wound up playing behind Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel in the Yankee outfield.”

— Hall of Famer Joe Sewell[i]

One wonders what might have become of a player like Benjamin Edwin Paschal had he actually been given the chance. Had the designated hitter existed in the 1920s, he might have been a household name. Instead, he spent the bulk of 364 major-league games batting .309 as a career backup to two men enshrined in Cooperstown (Babe Ruth and Earle Combs) and one who arguably could have been (Bob Meusel).

When the New York Yankees purchased Paschal’s contract from the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association in August 1924, the newspapers hailed him as the “Second Babe Ruth.” And although he never reached the level of Ruth’s reputation, by odd coincidence, Paschal’s career often paralleled Ruth’s on a much smaller scale. Born the same year, they started playing professionally at age 19 for their hometown team (and within weeks had made a major-league club), played for the Boston Red Sox before the Yankees, retired a year apart. Fittingly, Paschal is among a small handful of players to have pinch-hit for the Bambino.

They are all, of course, coincidences. Paschal might have had a fraction of the talent, but not a scintilla of Ruth’s flamboyant personality. If anything, Paschal resembled the more reticent Lou Gehrig in that respect – they were apparently roommates, after all.[ii] “There were three social segments on the club,” wrote Hall of Fame pitcher Waite Hoyt of the Yankees in the 1920s. “There were those whom we can label the movie-going set, and there were those who were inclined toward house parties and social gatherings, and then there was Babe Ruth, who stood alone.” Paschal, he said, along with Gehrig and others was among the movie-going set.[iii]

Benjamin Edwin Paschal was born on a farm in Enterprise, Alabama, on October 13, 1895, probably named for his paternal grandfather. His mother, Anna Marie Helms (who also may have gone by Emily)[iv], was 19 at the time of his birth and had already had a son, Robert, the previous year. His father, Charles, 13 years her senior and of French and English descent, died before Ben was 2. Sometime thereafter, Anna’s father, Andrew Helms, moved in to help tend to the farm and care for his widowed daughter and her two young sons. Anna was remarried briefly to Joe Davis and produced a daughter, Annie Davis, around 1905, then was widowed again.

The house where young Ben grew up is part of a trailer court now, but still stands. “It’s a little small bungalow house,” said his nephew, Robert Paschal, who spent his life in Enterprise. “I’d imagine it was a pretty good size house for the time.”

Ben attended elementary school in Enterprise for seven years, and when he was old enough he and his brother Robert helped out on the farm, possibly harvesting peanuts, corn, cotton, and other crops indigenous to that area. In his free time, he played baseball on the playgrounds with the neighborhood children.

Some sources (including his obituary) say Paschal played intercollegiate sports for the University of Alabama, but the school was unable to confirm that he suited up for the Crimson Tide,[v] and his nephew Robert doesn’t recall hearing that he went there. Addressing his education on a survey sent out by the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Paschal himself left the lines “High school attended” and “College attended” blank. Any higher education he may have had would have been brief – by 1915, he was already playing professionally.

Paschal debuted with Dothan (Alabama) of the short-lived Class D Florida-Alabama-Georgia League, as the property of the Cleveland Indians.[vi] One of his teammates was a 16-year-old pitcher named Bill Terry – who would later make the Hall of Fame as a first baseman. The team practiced in Battens Crossroads, a stone’s throw from Enterprise, and was in first place on July 17 when the league disbanded. Paschal, who in 64 games had batted .290 with seven home runs, was soon snapped up by Cleveland’s big-league club, which paid him $150 a month for the remainder of the season.

Paschal’s introduction to the major leagues came auspiciously on August 16 in the second game of a home doubleheader against Detroit. Curveball specialist Bernie Boland had not allowed the Indians a hit when Cleveland manager Lee Fohl summoned Paschal to bat for the woefully weak hitting pitcher Rip Hagerman[vii] with two outs in the eighth. The husky rookie mumbled his name to the umpire, who relayed it to the announcer.

“Paschal now batting for Hagerman,” the announcer said.

“What’s the name please?”

“Come again?”

“Where did they get him?”

According to the New York Times, Paschal had joined the Indians so quietly that “few knew there was such a player on the bench” that day.[viii] His name had not even been on the scorecard.[ix]

Paschal took Boland’s first pitch down the middle for a strike. The second one nearly beaned him and made him drop to the ground. But on the third pitch, a knee-high curve on the outside, Paschal took a robust swing and lined the ball cleanly into center field for a single – Cleveland’s only hit of the game. No one applauded. Boland would have to settle for a one-hitter.

“I suhtainly was sorry not to have Mistah Boland get his no-hit game,” Paschal said after the Indians’ 3-1 loss (with the papers obviously mimicking his country-boy drawl), “but you see, sah, we all is trying to break into this big league you all have got up here, and how am I going to bust in if I don’t bust the ball on the nose when they pitch it where I’m a-swinging?”[x]

Unfortunately for Paschal, he didn’t “bust” the ball at all after that, going 0-for-8 to finish out the season. The Indians liked what they saw, however, and invited him to spring training in 1916, but released him in March to New Orleans, which sent him to Charlotte of the North Carolina State League.

Initially chided for his poor fielding, Paschal hit his stride in Charlotte as a slugger. In 123 games, he pounded a league-high 15 home runs (an impressive feat in the Deadball Era) and won fans’ hearts as he led the Hornets to a pennant.

After quietly marrying Tommie Verna Barber in early 1917,[xi] Paschal split the season between Muskegon of the Class B Central League and Waterloo of the Class D Central Association, where his prodigious power and fleetness afoot continued to impress. Then the Central Association disbanded on August 7, and Paschal went home. With a war going on overseas and a new wife and young sister to support,[xii] Paschal turned his attention to tending his farm and starting a family. Ben Paschal, Jr., whom one paper described as a “husky youngster”[xiii] like his 5-foot-11, 190-pound father, was born on April 13, 1918.

In the spring of 1919 Charlotte president Felix Hayman attempted to lure Paschal back to the club, now in the newfangled Class B South Atlantic (Sally) League, but Paschal would have nothing of it. He wrote that he had a “mighty fine crop planted” that season that he could not afford to leave; however, he promised that when he did return to baseball, he would wear a Hornets uniform.[xiv] A year later, he honored his word.

From 1920 to 1923 Paschal became one of Charlotte’s favorite sons, leading the team in home runs each year. Enamored of the city, he eventually moved his family there. He considered his years in the Sally League the best time he had in baseball. Sportswriters called him Big Ben, Larruping Ben, Bustin’ Ben, Ben the Buster. Fans dubbed him the man “who hit sticks of dynamite” because of an incident involving a defective fence.

“I got hold of a ball,” Paschal remembered. “It was a line drive and it sailed square into the fence. Normally it would have bounced off but this time it hit a knot in the board just like it was hit by a sledgehammer. When the knot went, the board literally flew apart. It was a one in a million shot, but they called me a fence buster. I never took much time to explain.”[xv]

In 1920 he had a cup of coffee with the Boston Red Sox. “I’d like to go up there and give them a battle,” he said in July after the editor of the Charlotte Observer informed him that Red Sox scout Ed Holly was interested. “I believe I can crack a few up there, same as I have been doing down here.” He just hoped that the club would allow him to finish out the Sally League season. “The Charlotte folk have been nice to me and I like ’em,” he added.[xvi]

Paschal was purchased by Boston in July; he agreed to a $300-a-month contract for the balance of the season and batted .357 (10-for-28 – all singles) in nine games, and was returned to Charlotte at the end of the year. Apparently, the Red Sox were unimpressed with him defensively,[xvii] but planned to keep tabs on him.

“I didn’t mind that the Sox sent me back,” he said the following spring. “I like Charlotte and the people here and I had rather play ball at Wearn Field than anywhere else except the big leagues. If I had to come down again, I am glad it was to Charlotte.”[xviii]

On August 20 – shortly after the Hornets announced they’d sold him to Rochester – fate intervened to keep Paschal in the Queen City even longer. In the first inning of the opener of a doubleheader against Augusta, he broke his leg sliding into second base, and was sidelined for the remainder of the season. His Charlotte teammates collected $179 that day for Paschal to split with another recently injured player,[xix] and Rochester voided the sale.

Fully healed by the start of the 1922 season, Paschal returned with a vengeance, tearing up the Sally League over the next two years – including a .351 average, 200 hits, 26 home runs, and 22 triples in 1923 to lead the 89-56 Hornets to the championship.

His bat didn’t slow even after he was sold to Atlanta of the Class A Southern Association in 1924 – and scouts began vying for his services fast and furious throughout the season.[xx] Had opportunity better favored Paschal, he would have landed with the Cincinnati Reds, who lacked a consistent third outfielder. Atlanta and Cincinnati had tentatively agreed to a deal for $2,500 (money back guaranteed) plus $10,000 and a player to be named if the Reds retained Paschal for the 1925 season.[xxi] But the New York Yankees, a team already rich in outfield talent, had a working agreement with Atlanta, and scout Bob Gilks had also been looking Paschal over.

On August 13, 1924, the Yankees exercised the terms of their agreement with the Crackers and purchased Paschal for $20,000. In close contention with Washington for another pennant, New York was looking to compensate for having lost red-hot rookie Earle Combs to a season-ending ankle injury; the team planned to use the man some sportswriters heralded as the best all-around player in the Southern Association as a pinch-hitter down the stretch.

“But after that pinch hit, where to?” Paschal asked, perhaps sensing the turn his career might take.[xxii]

Paschal arrived in New York on a salary of $600 a month, went 3-for-12 (.250) with a double and three RBIs in four games during the final week of the season, and the Yankees finished two games behind of the Senators. In 1925 the Yankees signed Paschal for $3,000 for the full season.

Center field was up for grabs in spring training, and Combs got it, likely because he was the better fielder.[xxiii] Fair fortune favored Paschal as the Yankees made their way north to start the season, though, when Ruth collapsed in Asheville with “the bellyache heard round the world” a week before Opening Day.

Paschal got the call in right field and batted leadoff in the Yankees’ season opener against Washington. He hit his first big-league home run (and New York’s first round-tripper of the season) – a two-run shot to left off George Mogridge in the bottom of the sixth – as the Yankees defeated the world champion Senators, 5-1.

Tuning in from his bed at St. Vincent’s Hospital, The Babe smiled. “They don’t seem to miss me much,” he said.[xxiv]

But Ruth’s absence would be felt, as the Yankees stumbled into seventh place by late May – though Paschal was anything but the problem, at least statistically. Ironically (or perhaps fittingly), New York’s worst season of the decade (the team’s record wouldn’t dip below .500 again for another 40 years) was also Paschal’s best. In 22 of the Yankees’ first 40 games (17 of them starts), Paschal batted .373 (28-for-75), with six homers, 17 RBIs, 21 runs scored, and five stolen bases. But Ruth’s return to the lineup on June 1 sent him back to the bench.

“Everybody knows Ben Paschal is a natural .300 hitter, and if he takes over for Ruth he can do a bang-up job,” said Yankees manager Miller Huggins. “But if Ruth is out even for a day, you’ll notice right away the rest of them aren’t so cocksure of themselves. He’s the one guy they KNOWN [sic] will bring home the bacon.”[xxv]

Like many of Ruth’s teammates, Paschal also looked up to the Bambino. The two sometimes went on hunting trips together in eastern Carolina during the offseason. [xxvi]

“He was the best ever in helping a young player,” Paschal wrote of Ruth[xxvii] (who was older than him by mere months – but had nearly a decade more of big league experience).

But Ruth wasn’t quite Ruthian in 1925, and Huggins reinserted Paschal into the starting lineup in late August (shifting Bob Meusel over to third base) in the Yankees’ unsuccessful attempt to claw their way out of the American League doldrums. On September 8 Paschal homered twice in the second game of a doubleheader at Boston; on September 22 he went deep twice in the opener of a doubleheader against Chicago. All told, he finished the season batting .360 with 12 home runs, 56 RBIs (an American League record for a rookie with fewer than 250 at-bats), 49 runs scored, and 14 stolen bases in just 89 games.

Paschal’s performance gave him a little room to negotiate in 1926, and he returned three contracts to the Yankees before inking a $5,000 deal. He saw sporadic playing time as a pinch-hitter and late-game substitute, with the occasional spot start mixed in early on, but he started 34 straight games in right field from July 9 to August 11 after Meusel broke a bone in his foot. He alternated some with Combs in center field in September (likely strategic – Paschal batted from the right, Combs from the left), as the Yankees reclaimed the American League pennant.

Had the Yankees not lost the World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals, Paschal’s lone Series hit, in Game Five, might have been the turning point. With the Series tied at two games apiece and the Yankees down by a run in the top of the ninth, he pinch-hit a game-tying RBI single off Bill Sherdel to short center, and New York won in extra innings. The Yankees had the Cardinals on the brink of elimination, but lost the final two games.

Add that hit to another productive season (.287, seven home runs, 31 RBIs in 96 games), and Paschal put himself in line for another raise – and was “well pleased”[xxviii] with the terms of his $7,000 contract for 1927, the most he’d ever make.[xxix]

On the most celebrated of Yankees teams, Paschal was a mere footnote. Led by Ruth’s 60 home runs and Gehrig’s 175 RBIs, Murderers’ Row (a term coined a few years before, but used most famously to describe the 1927 squad) smashed their way through the record books, going 110-44 and sweeping the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. With Combs and Meusel healthy and thriving most of the year, as well, there was little need for any other outfield lineup – though whenever Paschal was called, he made himself count.

On Opening Day Paschal made his way into the trivia books as the last man of a select few who pinch-hit for Babe Ruth.[xxx] According to Fred Lieb of the New York Post, the Bambino, who was 0-for-3 with two strikeouts in the game, suffered a “bilious attack” in the sixth inning – “something he had eaten, and he couldn’t see the ball.”[xxxi] Paschal smacked an RBI single off Lefty Grove.

On June 13 Paschal came within inches of becoming the first modern big leaguer to hit four home runs in a game. As the city of New York feted Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic, only 20,000 showed up to watch the balding man subbing for Meusel hit two inside fastballs into the left-field seats in his first two at-bats. In two other at-bats, Paschal hit a pair of hard liners to right that barely missed clearing the wire screen in front of the bleachers. The final tally: two home runs, a double, and a triple.

“Mac, I’m getting a hold of that apple today, but there doesn’t seem to be any luck with me,” Paschal told umpire Bill McGowan upon arriving at third base in his final at-bat. “Just missed my third homer again by a few inches. Gee, I’d like to join the class of ‘three home runs per game’ hitters.”

“Well, Ben, if you had any luck, if the wind had been blowing toward the foul lines you would have been the third man in major league baseball to have hit four homers in a single game,” McGowan replied.

“That’s right, Mac,” Paschal said wistfully, “four in one game would just about put me up there with the stars, I guess.”[xxxii]

Curiously, these were the only two home runs Paschal hit in a season limited to 87 plate appearances. He batted .317.

Paschal rode the bench during the World Series sweep, but his blinding speed petrified Pirates fans as he chased after Ruth’s fly balls to all corners of the outfield.[xxxiii]

“Don’t hit any more out here!” he shouted to Ruth, gasping for breath. “Two of those balls haven’t come down yet.”[xxxiv]

Being the little man on the best team in baseball made any player big, though, and Paschal was aware of his fans, particularly in the Charlotte area, where he and his family had settled and he ran a local garage in the offseason. When a former employee at the nearby Gastonia Gazette took ill and requested a baseball signed by Ruth, Paschal, and possibly the rest of the Yankees, Paschal dutifully responded two weeks later to the mutual acquaintance who wrote him. Not only did he send a ball autographed by the entire team, he paid for the shipping.

“I am always glad to do what I can for the sick and there is no expense. It is all on me,” read the note he enclosed.[xxxv]

Generally a “reserved, quiet-type person” and “a good man” (as his nephew remembered him), Paschal did have his moments of disagreement with the umpires. Bill McGowan once tossed from a game against Boston for calling him “Little Willie from Wilmington, the talk of the league!”

“Hang it!” said Paschal, justifying his behavior to writer John Kieran. “That’s what he calls himself, and I was just agreeing with him.”[xxxvi]

He also wasn’t averse to talking smack, his booming baritone jockeying opposing hitters during batting practice,[xxxvii] and rattling pitchers on the mound.[xxxviii] Before the Yankees played the Cardinals again (and won) in the 1928 World Series, he revealed his own brash predictions regarding St. Louis’s Game One starter, Bill Sherdel.

“We got his goat,” said Paschal, remembering his big hit two years earlier. “He can’t beat us.”[xxxix]

Starting two games in center field in place of the injured Combs, Paschal went just 2-for-10 in the Series (including a pinch-hit RBI single), but the Yankees hit Sherdel hard, and rolled over the Cardinals in four games for back-to-back titles. Coming off a regular season in which he batted .316 in just 92 plate appearances, Paschal probably couldn’t ask for much more.

But then, at 33, he was no longer a young man by baseball standards, and the Yankees seemed to be stockpiling strong reserve outfielders who would never break through the Ruth-Combs-Meusel bulwarks. Which could only mean one thing for a $7,000-a-year sub like Paschal: trade bait. Indeed, New York placed him on waivers several times in 1928 and ’29, dangling his name in talks for Philadelphia A’s pitcher Eddie Rommel, or in a package deal for the Washington Senators’ Bobby Reeves, a supposedly up-and-coming infielder.[xl]

Symbolically (perhaps intentionally), when the Yankees wore numbers for the first time in 1929 based on their place in the batting lineup, Paschal was given No. 25 – as the final man on the roster. His reaction after hitting a pinch-hit home run on July 1 that won the game in front of a hostile Boston crowd was telling:

“Just about time I hit one,” he said defensively to a reporter for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (who might have interviewed him only because he couldn’t track down the more fiery Leo Durocher). “Perhaps if I was in there every day—a fellow gets cold sitting on a splinter so long between hits. But I wasn’t cold this afternoon.”[xli]

Paschal’s batting average that season fell to .208, and after the Yankees’ disappointing finish that year (not to mention the fairly sudden death of manager Miller Huggins), he and the team parted ways. On November 9, 1929, New York sold him to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association along with Wilcy Moore and Johnny Grabowski for catcher Bubbles Hargrave.

Although he never returned to the majors, Paschal’s four seasons in St. Paul were nothing to scoff at. Playing full time again, he hit .350 in 1930; when the Saints broke the American Association record for runs scored in a game in a 23-4 victory over Toledo that August 22, Paschal led the attack with four hits and four RBIs. In 1931 his .336 average helped St. Paul to a league championship. And on June 4, 1932, against Milwaukee, Paschal tied a league record for hits in a game by going 6-for-6 (three singes, three doubles). But after he lost a step or two in 1933, the Saints released him as part of a radical roster overhaul that offseason.

In 1934, despite talks that Paschal might return to Charlotte to manage the Piedmont League team, he signed with Knoxville of the Southern Association, perhaps as a favor to new manager and good friend Pee Wee Wanninger.[xlii] He was expected to bat cleanup and add power to the Smokies’ lineup, but after Wanninger quit two days before the season started because of a disagreement with ownership,[xliii] Paschal didn’t last long, released after 38 games.[xliv] He returned to Charlotte and managed a semipro team, Baldwin of the Catawba league, effectively calling it quits on his professional career.

Paschal became a salesman for Cunningham Wholesale Co. in Charlotte. Sometimes people would recognize him when he would return to visit family in Enterprise and watch the local Class D team, but indications are that he had little to do with baseball after he retired. In fact, by 1974, when the Yankees were in the process of forming an alumni association for ex-ballplayers, the club had lost track of his whereabouts.[xlv]

Whether the Yankees reconnected with him, it turned out, made little difference, as a few months later, on November 10, 1974, he succumbed to arteriosclerotic heart disease at Presbyterian Hospital in Charlotte at the age of 79. He was buried next to his wife, Tommie (who had died the previous year), in Sharon Memorial Park in Charlotte.

—

Special thanks to Gabe Schechter, formerly at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; Robert Paschal for his recollections of his uncle; the reference assistants at the Hoole Library at the University of Alabama for attempting to track down what probably didn’t exist; and Gary Sarnoff for sharing some of his research. All statistics, unless otherwise noted, are from baseball-reference.com. All salary amounts are from the contract cards for Ben Paschal on file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

April 11, 2011

[i] “Joe Sewell Is Qualified When It Comes To Hitting.” Anniston Star. 18 Jul 1969.

[ii] Bolton, Mike. “Ben Paschal Played With Babe Ruth” Enterprise Ledger, Ben Paschal file, Baseball Hall of Fame archives. Also affirmed by nephew Robert Paschal in an interview with the author, August 12, 2009. The author finds the credibility of both these sources slightly suspect, but was never able to refute this assertion either, and chooses to believe there is some truth to Paschal and Gehrig rooming together at some point.

[iii] Fleming, G.H. Murderer’s Row: The 1927 New York Yankees. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1985. Foreword, p. 14.

[iv] Paschal’s death certificate says the former; multiple census records say the latter.

[v] Author’s correspondence with reference assistant J. Robertson McIllwain, W.S. Hoole Special Collections Library, University of Alabama, November 27, 2007; further correspondence with reference assistants Jenna Weber and Kevin Ray, December 23, 2010.

[vi] His transactional card filed in the Baseball Hall of Fame carries the notation, “C. 8/19/15 A. with Cleveland 9/22/14.” The author was unable to uncover how (and by whom) Paschal was first discovered.

[vii] The previous year, 1914, Hagerman had gone 1-for-61 (.016).

[viii] Evans, Billy. “Single-Hit Games in the American League.” New York Times. December 5, 1915. Paschal had pinch-hit for pitcher Lynn Breton in the first game of the doubleheader, but seeing the Indians were losing by four in the ninth inning and the bases were empty, perhaps few noticed.

[ix] “Spoiled No-Hit Game.” The Morning Leader. August 26, 1914.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] The Montgomery Advocate on March 11, 1917, listed the wedding as having taken place the previous Thursday – that is, March 8. Paschal listed his anniversary as April 1, 1917. on a Hall of Fame survey. The author has been unable to reconcile the discrepancy.

[xii] World War I draft card, dated Jun4 4, 1917.

[xiii] “Ben Paschal Is Strong With Fans,” Spartanburg Herald, 10 Apr 1921.

[xiv] “Along The Sport Trail With The Old Scout: Ben Paschal,” Charlotte Sunday Observer, April 20, 1919.

[xv] UPI obituary, printed as “Ex-Yank Paschal Succumbs” in Mansfield News Journal. November 13, 1974.

[xvi] “Paschal Anxious for Chance on Big Time,” Charlotte Observer, July 5, 1920.

[xvii] “Ben Paschal Is Strong With Fans,” Spartanburg Herald, April 10, 1921.

[xviii] Brietz, Eddie, “Citrano, Brown, O’Connell and Whelan Report,” Charlotte Observer, April 4, 1921.

[xix] “Ben Paschal’s Leg Broken in Sliding,” The Spartanburg Herald, 21 Aug 1921.

[xx] Although Paschal batted right-handed, newspaper accounts around the time he was sold to the Yankees indicated that he might have done some switch-hitting, at least in Atlanta.

[xxi] Correspondence between Cincinnati Reds president August Herrmann and Atlanta president Daniel Michalove, August 8, 1924, et seq, Ben Paschal file, Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

[xxii] Brown, Norman E., “New Yankee Member is Ben Who Once Pinch Hit Himself Out of Majors,” Hamilton Evening Journal, August 21, 1924.

[xxiii] “Centerfield Is Only Doubtful Yank Position,” Bridgeport Telegram, February 28,, 1925.

[xxiv] New York Times, April 15, 1925.

[xxv] “’Big Man’s’ Value In Any Sport Is Shown In Career of Babe Ruth.” Chicago Defender, May 3, 1958.

[xxvi] “The King of Swat Once Got Sick in Asheville,” The Landmark, August 19, 1948.

[xxvii] Survey on “Babe Ruth’s Playing Style and Personality,” Professor Marshall Smelser, University of Notre Dame; Ben Paschal file, Baseball Hall of Fame archives.

[xxviii] Washington Post, February 18, 1927.

[xxix] Considering that Paschal didn’t play every day, $7,000 was actually quite a bit of money. According to The Sporting News on October 22, 1977, regulars Pat Collins and Mark Koenig made the same salary that year, and young stars Lou Gehrig and Tony Lazzeri were being paid just $1,000 more – and none of the other reserve position players were making more than $5,000 (and most of them less).

[xxx] Ruth was pinch-hit for a few times during his pitching days, but on only one other occasion after he became a full-time outfielder, when Bobby Veach went in to bat for him on August 9, 1925.

[xxxi] Article excerpted in Fleming, G.H., Murderer’s Row: The 1927 New York Yankees (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1985), p. 94. Lieb and other accounts suggest that alternatively Ruth may have been simply disgusted with his performance that day and wanted out.

[xxxii] McGowan, Bill. “Busy With Yanks, Sees Little of Lindbergh.” Delmarvia Star. June 19, 1927.

[xxxiii] “Sidelights of World’s Series.” AP report, Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, October 5, 1927.

[xxxiv] “World Series Sidelights,” AP report, Morning Leader, October 5, 1927.

[xxxv] “New York Yankees Autograph Baseball And Send It To E.R. Gamble.” Gastonia Daily Gazette, July 29, 1927.

[xxxvi] Kieran, John, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, August 19, 1928.

[xxxvii] New York Sun, May 18, 1928.

[xxxviii] Ruth, Babe. “Shires, Durocher Real ‘Jockeys,’ ” Telegraph Herald and Times Journal, August 22, 1929 (The Christy Walsh Syndicate).

[xxxix] Kirksey, George. “Yankees ‘Shoot the Works’ Against Cardinals.” (United Press report), Binghamton Press. October 4, 1928.

[xl] Stewart, Dixon. “Tenth Man in Line Up Seems Unpopular.” (United Press report), Oelwein Daily Register. December 13, 1928.

[xli] Burr, Harold C. “Riding by the Red Sox So Upset Paschal He Made Pinch Homer.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 2, 1929.

[xlii] “Paschal a Pal to Wanninger.” The Sporting News. January 11, 1934. Wanninger, also born in Alabama, and Paschal were teammates on the 1925 Yankees, and roommates in St. Paul.

[xliii] Levy, Sam. “Peewee Wanninger Signed by Brewers to Bolster Infield.” Milwaukee Journal. May 1, 1934.

[xliv] Baseball-reference.com says Paschal also played 18 games with Scranton of the New York-Penn League and 90 games with Jeanerette of the Evangeline League that year, but on a Hall of Fame survey years later Paschal listed “Knoxville Tenn. 1934” as the answer to the question, “What was your final year of professional baseball?”

[xlv] “Yanks Seek Addresses of 13 Former Players.” The Sporting News, June 8, 1974.

Full Name

Benjamin Edwin Paschal

Born

October 13, 1895 at Enterprise, AL (USA)

Died

November 10, 1974 at Charlotte, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.