Johnny Grabowski

When the curtain rose on the New York Yankees’ 1929 season, for the first time in team history each ballplayer wore a numbered jersey. Catching for New York that day was John Grabowski, the large block 8 on his back signifying his spot in the batting order. One of three backstops that Yankee manager Miller Huggins alternated like tag-team wrestlers during the team’s World Series championship seasons of 1927 and 1928, Grabowski was anointed the every-day catcher for the 1929 campaign. However, an injury opened the door for future Hall of Famer Bill Dickey to take his job – and eventually his number too.

When the curtain rose on the New York Yankees’ 1929 season, for the first time in team history each ballplayer wore a numbered jersey. Catching for New York that day was John Grabowski, the large block 8 on his back signifying his spot in the batting order. One of three backstops that Yankee manager Miller Huggins alternated like tag-team wrestlers during the team’s World Series championship seasons of 1927 and 1928, Grabowski was anointed the every-day catcher for the 1929 campaign. However, an injury opened the door for future Hall of Famer Bill Dickey to take his job – and eventually his number too.

Grabowski was a part-time catcher with the Chicago White Sox before his time with New York and the Detroit Tigers after. Known as “Nig” or “Grabby” as well as John or Johnny, his chief attributes were his arm and defense. Babe Ruth called Grabowski’s head-over-heels dive into a Philadelphia dugout “the greatest bit of foul fly catching I ever saw.”1 The ensuing controversy prompted a rule still in place almost a century later.2

Grabowski “kept to himself and rarely asked for advice” during his time with the Yankees, according to Lou Gehrig biographer Alan D. Gaff, but he was a favorite of hurler Urban Shocker. He could spit tobacco juice through his catcher’s mask “with unerring accuracy,” providing a secondary source of fluid for Shocker’s money pitch, the spitball.3

John Patrick Grabowski was the first child born to Honora and Joseph Grabowski, on January 7, 1900, in the textile mill town of Ware, Massachusetts – the birthplace, five decades earlier, of curveball pioneer Candy Cummings. Born in Poland, Joseph and Honora emigrated to the US in the 1890s and became citizens in 1896. By 1910 the family had grown to include three young girls, and lived in Schenectady, New York, a fast-growing city that was home to several thousand Polish immigrants.4 A few years later the Grabowskis welcomed a second boy into the family, Joseph. A house painter when John was born, the senior Grabowski was listed as a Schenectady city hall janitor in the 1920 US census.5

At Electric City’s McKinley Intermediate School, young Grabowski played on a school baseball team that won the 1913 public school championship.6 A pitcher and infielder as he reached high school age, he switched to catching to fill a need on his semipro team.7 He attended Schenectady High but rather than join the school’s nine, he elected to play for local community teams, developing a reputation “as a speedy backstop and heavy hitter.” 8

When the Schenectady Knights of Columbus formed a team in 1920, Grabowski was one of the first players signed by manager Hank Bozzi, later owner of the Mohawk Colored Giants of Schenectady. Bozzi put him in the middle of the batting order and had him catch.9 Twice during the season, Grabowski traveled with the Albany Senators of the Eastern League as an un-rostered backup catcher but appears to have never made it into a game.10 Once the K. of C. season ended, Grabowski played for the Union Bag semipro team in nearby Hudson Falls. During a 1-1 Halloween tie with a local team, he batted against Cincinnati Reds spitballer Ray Fisher, who one year earlier had faced the Chicago “Black Sox” in the 1919 World Series.11

While playing for Union Bag, Grabowski attracted the attention of former Brooklyn Superba Phil Lewis, who gave a glowing recommendation to New York Giants coach Hughie Jennings. Jennings offered Grabowski a contract, but the youngster balked at the prospect of being sent to an unspecified minor-league team if he failed to make the big-league squad.12

After the baseball season Grabowski moved inside to play guard in local winter basketball leagues, where he was typically his team’s high scorer.13 He continued to play in Schenectady winter hoops leagues through early 1927.14

Convinced he’d found a diamond in the rough, Lewis rebounded from Jennings’ swing-and-miss to sing Grabowski’s praises to Joe Cantillon, manager of the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers. Cantillon contacted Grabowski and in February inked him to a contract.

Grabowski made the Millers’ Opening Day roster but was the number three catcher on a team that needed only two. He was optioned to the Saskatoon Quakers of the Class-B Western Canada League before getting into a game.15 Despite his brief Twin Cities stay, Grabowski left a good impression. “This Grabowski boy is a real catcher,” said the Minneapolis Tribune in reporting his demotion. “He can hit and he can catch and all of the pitchers, especially [clean member of the 1919 Black Sox] Grover Lowdermilk, say he can catch well and they ought to know.”16

Playing for Saskatoon’s first-year manager John Hummel, Grabowski showed so much “prowess with the willow” that a local newspaper claimed he “look[ed] to be the ‘Babe Ruth’ of the Western Canada circuit.17 By the end of June he was hitting .272 over 37 games, while demonstrating “a sweet peg to second” and posting a .977 fielding percentage, second-best among league catchers.18 Called up to Minneapolis in late July to fill in for a backstop who’d broken a finger, he was let go weeks later for the same reason.19

Minneapolis sold Grabowski’s rights to the St. Joseph Saints of the Western League in the offseason, reportedly at his request after being told he wouldn’t be the Millers’ regular backstop.20 Rather than catching every day, Grabowski got a preview of how much of his career would play out. With a pitching staff that included a mix of former major-leaguers and several still in the making,21 Saints manager Wally Smith evenly split playing time between Grabowski and another righty-hitting backstop. He hit .289 with 21 doubles and five home runs, though a gashed hand cut his season short in mid-September.22

Grabowski’s solid 1922 campaign earned him a promotion back to Minneapolis in 1923. Playing behind journeyman backstop Wally Mayer, he hit .317, with 100 hits in 98 games. On defense, he turned heads when he threw out three would-be base stealers in one game.23 After watching Grabowski in a midseason contest, Cleveland Indians scout Charlie Hickman called him “the best looking catcher [he’d] seen in four [minor] leagues.” Hickman elaborated, “He appears to be a brainy lad and possesses a whale of an arm. I like the way he stands up at the plate, too. He looks like a natural hitter to me… ripe for a tryout in the big show.”24

The Indians weren’t the only team to notice Grabowski. In December, both Cincinnati Reds manager Pat Moran and the Yankees’ Huggins extended offers for Grabowski to Millers owner Mike Kelley, but both were turned down.25 Midway through the next season, Chicago White Sox owner Charlie Comiskey made Kelley an offer he couldn’t refuse. Looking to beef up a team stuck at .500, Comiskey acquired Grabowski and his roommate, Millers ace Leo Mangum, in exchange for infielders Ray French and Bill Black, catcher Elwood “Kettle” Wirts, pitcher Doug McWeeny, $25,000, and a pitcher to be named later who seemingly never was.26

Batterymates with Albany (maybe), St. Joseph and Minneapolis, Mangum and Grabowski debuted together for Chicago on July 11 at year-old Yankee Stadium, hours after arriving from Minnesota.27 Grabowski was struck out by Bullet Joe Bush in his only plate appearance, as manager Johnny Evers pinch-hit for him early in a loss to the defending World Series champions. Installed as the Sox’ third-string catcher behind declining future Hall of Famer Ray Schalk and second-year backstop Buck Crouse, Grabowski posted the highest fielding percentage of the group in 19 games (.972), but managed an OPS+ of only 51.

As was then common, Grabowski barnstormed after the 1924 season, with Bill McCorry’s All Professionals, a team comprising mostly Eastern League ballplayers.28 Money that Grabowski earned playing foes like Chappie Johnson’s Stars, an independent Negro League team, came in handy; by then the 24-year-old had a wife, Janet, and a young daughter, Helen.29

By the end of the 1924 season, veteran second baseman Eddie Collins was at the helm for the last-place White Sox, the last of four managers Comiskey tried.30 Collins maintained the same pecking order among his catchers in 1925, which meant only 21 appearances for Grabowski. He hit .304, collected 10 RBIs and went 7-for-15 (.467) in the four games that he caught to completion.31

Before the 1926 season, Grabowski candidly assessed his situation. “Of course, I would like to work regularly but I realize that I must play the ‘catcher-in-waiting’ role to the great little Schalk.”32 A week into the season he still hadn’t gotten a start – but as a pinch-hitter, he clubbed his first career home run, a three-run blast off Cleveland’s Joe Shaute in a 9-5 loss. Over 122 at-bats that year, Grabowski collected only two other extra-base hits. He was behind the plate in 38 games, including Ted Lyons’ August 21 no-hitter over the Red Sox.33

Unable to lead the White Sox into the first division, Collins was released in November 1926, and Schalk became Chicago’s next manager.34 Two months later, Grabowski and infielder Ray Morehart were sent to the Yankees for Aaron Ward, a solid second baseman who’d been displaced by young Tony Lazzeri.35

Nominally 5-foot-10 with a playing weight of 185 pounds, Grabowski was heavier than manager Huggins wanted upon reporting to his first Yankee spring training. Huggins had him run laps around the field after both morning and afternoon practices to “lose that look of … heavyweight wrestlers.”36 Grabowski struggled with his weight throughout his time as a Yankee. Sportswriter Marshall Hunt raised an alarm about this near the end of the 1928 season,37 and when the backstop requested permission in February to drive from Schenectady to the team’s St. Petersburg camp, executive Ed Barrow quipped, “it would be better for you to run all the way down.”38

Defending AL champions, the 1927 Yankees boasted a record-setting, power-laden offense featuring “Murderers’ Row.” Led by Ruth, Lazzeri, veteran Bob Meusel and a young Gehrig, the Yankees had paced the majors in home runs the year before, but their catching corps committed more throwing errors than any AL squad (14), and gunned down a lower percentage of prospective base stealers than all but the last-place Red Sox. The addition of Grabowski gave New York “at least one good throwing catcher,” in the preseason opinion of sportswriter Frederick G. Lieb, to go along with holdovers Pat Collins, an offense-first backstop, and Benny Bengough, who was still recovering from an arm injury he’d suffered late in the 1926 season.39 Said former big-league umpire Billy Evans of Grabowski, “No catcher in the majors has a better arm.”40

Grabby earned the nod as Huggins’ Opening Day catcher against the Philadelphia A’s, paired with hard-throwing Waite Hoyt. The next day, he appeared in a newsphoto published nationwide showing Ty Cobb’s first-inning at-bat – the Georgia Peach’s first with Philly after 22 years in Detroit.41

Grabowski sat out the second game of the season, as Collins caught lefty Dutch Ruether. That pattern held through late July: regardless of who was pitching for either side, Huggins started Grabowski in odd-numbered games and Collins in even-numbered ones.42 All the while, New York was steamrolling all comers, going 71-27-1 (.725) to open up a 13-game lead.43

Luke Sewell’s foul tip on July 29 wounded Grabowski’s right hand, sidelining him for four weeks.44 In his first game back as a starter, he got spiked in the same hand on a tag play, causing him to miss another three weeks.45 When he returned in mid-September, Grabowski became the third wheel in the catching rotation of Collins and Bengough that Huggins had instituted in his absence. On September 27, Grabowski was on second base when Ruth clubbed a grand slam off Lefty Grove, the only one of the Bambino’s record-setting 60 home runs that Grabowski saw from a basepath.

Grabowski delivered on defense for New York in 1927, committing half as many errors and passed balls as Collins did, while catching roughly 75 percent as many innings. To the contemporary fan, he seemed to hold his own on offense, hitting .277, two points higher than Collins, but his OPS was almost 150 points lower.

Grabowski’s supporters back home in Schenectady cared little about his statistics. On Sunday, June 26, “more than 2,000 fans, fannesses and fanatics” trekked down to the Bronx for “Grabowski Day.”46 A committee representing the throng presented their hometown hero with a check for $1,300 and a lifetime membership in the Fraternal Order of Eagles.47

As expected, Huggins continued his three-catcher rotation in the World Series. Collins started in the opener against the Pirates at Forbes Field, with Bengough handling Game Two, both won by the Yankees. Nursing a broken finger he’d been quiet about,48 Grabowski started Game Three at Yankee Stadium, paired with 19-game winter Herb Pennock. Hitless in two at-bats, he was lifted for a pinch-hitter at the front end of a six-run rally in the seventh inning. The Yankees won and completed their sweep of Pittsburgh the next day with Collins catching. Grabowski earned a World Series share of just under $5,600 – outstripping his $5,500 salary.49

During the offseason, Grabowski enticed a few teammates to Schenectady for some friendly competition. He teamed with Hoyt in an exhibition baseball game days after the World Series,50 and in February hosted a basketball game with “Larrupin’ Lou [Gehrig]’s” Stars. Playing with a group of Schenectady “professionals,” Grabowski outscored Columbia Lou, four points to none.51

A few weeks before training camp opened in 1928, a new rule was adopted across the AL to address the uncertainty associated with a play Grabowski had made back on Decoration (now Memorial) Day. In the second game of a doubleheader with the A’s at Shibe Park, Philadelphia’s Al Simmons lofted a popup near the A’s dugout with one out and two runners on. Grabowski hustled over to make the catch, but unable to stop, flipped over a dugout railing and went head-over-heels down the stairs leading to the A’s dressing room. As he struggled to get out of the dugout, both baserunners, Ty Cobb on second and Eddie Collins on first, came around to score.52 Huggins objected to both runners scoring, and so the umpires caucused. AL ground rules addressed balls carried out of play from fair territory (i.e., over an outfield wall) but were silent on balls carried out of play from foul territory. Collins was allowed to score but Cobb was sent back to third. After the A’s lost by a run, manager Connie Mack formally protested but was denied by AL president Ban Johnson.53 An umpires’ conclave in February 1928 agreed to award runners one base “when a catcher or any other player catches a ball and falls into the dugout, field box or any other portion of the ball yard which is not on fair playing territory.”54

Heading into the 1928 campaign, Huggins announced that he intended to carry four catchers; Grabowski, Collins, Bengough, and a strapping 20-year-old Louisiana native, Bill Dickey.55 Grabowski shared catching duties at the outset of the season with Collins as Bengough nursed a sore arm and Dickey rode the bench. Once Bengough was cleared to play, Dickey was optioned to Double-A Buffalo, and Huggins went to a three-catcher rotation.

Up by 13½ games over second-place Philadelphia in early July, the Yankees came back to the pack over the next two months. His team tied with the Mackmen after getting swept in a September 7 doubleheader, Huggins benched both Grabowski and Collins in favor of Bengough, as the pair had “failed to hold up a slipping and sliding Yankee pitching staff.”56 Grabowski made only two more regular season appearances, both as a late-inning substitute, as the Yankees held off the A’s to win their third consecutive AL pennant. He finished the season with a career-high fielding percentage (.987) but batted a paltry .238.57 He watched from the sidelines as the Yankees swept the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series.

In a reversal, Grabowski was the last backstop standing at the end of training camp in 1929. Collins had been sold to the Boston Braves, Bengough was recovering from a tonsillectomy on top of his usual spring arm issues, and Dickey was too green for Huggins’ comfort. Grabowski handled the catching solo for the team’s first six regular season games.

Midway through the Yankees’ seventh game, on April 27, Jimmie Foxx’s foul tip split the pinky on Grabowski’s throwing hand, forcing him out of the game.58 Dickey started the next day, going 2-for-4 and gunning down the one baserunner who attempted to steal. By the time Grabowski’s finger healed, three weeks later, he was out of a job. He caught 15 games as Dickey’s backup before getting benched on June 27. With New York long out of the pennant race, Grabowski was sent home on September 22.59 Two days previously, Huggins, run down, worn out, and fighting a skin infection, had checked into a hospital. Within a week he was dead.

Over the winter, the Yankees reshaped their roster for their new manager, Bob Shawkey. Grabowski, reliever Wilcy Moore, and outfielder Ben Paschal were traded to the St. Paul Saints for catcher/manager Buddie “Bubbles” Hargrave, and Grabby’s number 8 was reassigned to Dickey. In 1972, the Yankees retired that number to honor both Dickey and another Hall of Fame catcher who wore it on his pinstriped jersey, Yogi Berra.

As St. Paul’s number one catcher, Grabowski shepherded the youngest pitching staff in the American Association, one that included a pair of 21-year-old future Yankee stalwarts; Lefty Gomez and Johnny Murphy. A fixture in the middle of the Saints’ batting order,60 he hit .285, with eight triples and nine home runs, and was named to the AA’s all-star team.61

Quiet as a Yankee, Grabowski opened up after leaving New York. He shared a favorite joke in a syndicated column,62 and offered thoughts about his former teammates. He claimed Pennock did his best without signs from the catcher, and called Shocker the smartest member of the 1927 pitching staff.63 Grabowski also took credit (dubiously) for goading Ruth into committing a costly act of defiance back when he was a White Sox catcher; enticing the slugger to swing away into a ninth-inning double play with the Yankees down a run, rather than bunting two runners over as instructed.64

In November 1930, the Detroit Tigers acquired Grabowski from St. Paul in exchange for pitcher Johnny Prudhomme and two unnamed players who turned out to be one, shortstop Joe Morrissey.65 The year before, Detroit had relied on inexperienced backstops who proved defensively challenged. The addition of Grabowski, 18-year veteran Wally Schang, and unnamed “replacements in center field,” gave them “immeasurably more defensive stability.”66

As the primary backup to Ray Hayworth, Grabowski caught roughly once every four games. Given the opportunity to finish more than 90 percent of his starts, he had the highest range factor (putouts plus assists) per game of his career (4.82). He hit .235, with one home run, off Cleveland’s Pete Jablonowski. Of Polish descent as Grabowski was, Jablonowski changed his last name to Appleton a few years later, reputedly at the request of his bride, who’d gone through life with the surname Leszcynski and wanted a simpler one as a Mrs.67

As it turned out, Detroit’s team defense fell from league average to below average in 1931, with a concurrent drop in power on offense relegating the team to seventh place. The Tigers parted company with Grabowski after the season, selling his contract to the Montreal Royals of the International League. Playing for a quartet of managers over the next two seasons, Grabowski shared catching duties first with pugnacious George Susce,68 and then with Bennie Tate, the Washington Senators catcher who was behind the plate on September 30, 1927, when Tom Zachary surrendered Babe Ruth’s record-setting 60th home run.

During a game in Toronto on August 30, 1933, Grabowski broke his leg stumbling into second base on a broken play, ending his season.69 Released by Montreal the following spring, he chose to end his career where it began, on Canadian soil. He settled into playing semipro ball and, with Prohibition repealed, opened a Schenectady tap room.70

His name had long been a source of mirth – newspapers had latched onto the coincidence of a catcher named Grabowski back in 1921.71 Grabby was also the protagonist in some fanciful stories. A Montreal Gazette sportswriter claimed that former White Sox outfielder Smead Jolley laughed so hard at a tale Grabowski told that he fell off a porch and rolled into a lake.72 Long before his touching Gehrig biography was adapted into the movie The Pride of the Yankees, writer Paul Gallico fantasized that Grabowski’s pneumatic chest protector expanded so much during a hot summer day in New York that he floated up out of Yankee Stadium and drifted all the way to Europe.73

In the mid-1930s, Grabowski took up umpiring. A good word from former Royals executive Frank “Shag” Shaughnessy opened the door in 1935 for the International League to hire Grabowski as an arbiter.74 He worked games in the Can-Am League for a few months the next year, and in 1937 was appointed to the New York-Penn League’s umpiring staff.75 From 1938 through much of the 1940 season, Grabowski was an Eastern League ump.76 His first marriage ended sometime during this period, as the 1940 US census shows him living with his father and one of his sisters.

“A good ball and strike umpire,” with a reputation for not being a homer, Grabowski deftly navigated controversy on the diamond.77 Together with future major-league umpire Al Barlick, in 1939 he was singled out as having the courage to stand up to unhappy managers.78 When Barlick was promoted from the IL to the National League a year later, Grabowski backfilled him, then joined the IL umpiring staff full-time in 1941.79 IL managers learned that Grabowski didn’t take any guff. When Montreal’s Clyde Sukeforth instructed one of his hitters to intentionally draw a catcher’s interference call by striking an opponents’ mask, Grabowski didn’t hesitate to toss him.80

Outside of umpiring season, Grabowski worked as a toolmaker at Schenectady’s American Locomotive and General Electric plants, applying a trade he’d learned in years past.81 With the onset of World War II, many American factories turned to producing equipment for the military, including those in eastern New York. Possessing a skill essential to the war effort, Grabowski was given an ultimatum in the midst of the 1942 baseball season: return to a defense job or face induction into the Army. He abandoned his umpiring career, and for the remainder of the war helped the American Locomotive company build tanks.82

On the morning of May 19, 1946, fire consumed Grabowski’s home in Guilderland, New York. He carried his second wife, the former Lorraine Stein, to safety after she’d suffered burns across much of her body, but was badly burned himself trying to pull his car out of the garage.83 Grabowski succumbed to his injuries four days later at St. Peter’s Hospital in Albany, and was buried in Schenectady’s Park View Cemetery.84 “It’s hard to believe that the Babe, Lou, Lazzeri, Hug, Herb Pennock and a good catcher, John Grabowski have all passed on,” Yankee teammate Bob Meusel said a few years later.85 Lorraine, who’d survived two fatal car crashes long before the house fire, lived until 1983.86

On February 4, 2008 – the 80th anniversary of his hoops tilt against “Larrupin’ Lou’s” Stars, and 90 years after graduating from high school – Grabowski was chosen for induction into the Schenectady city school district’s Athletic Hall of Fame.87

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

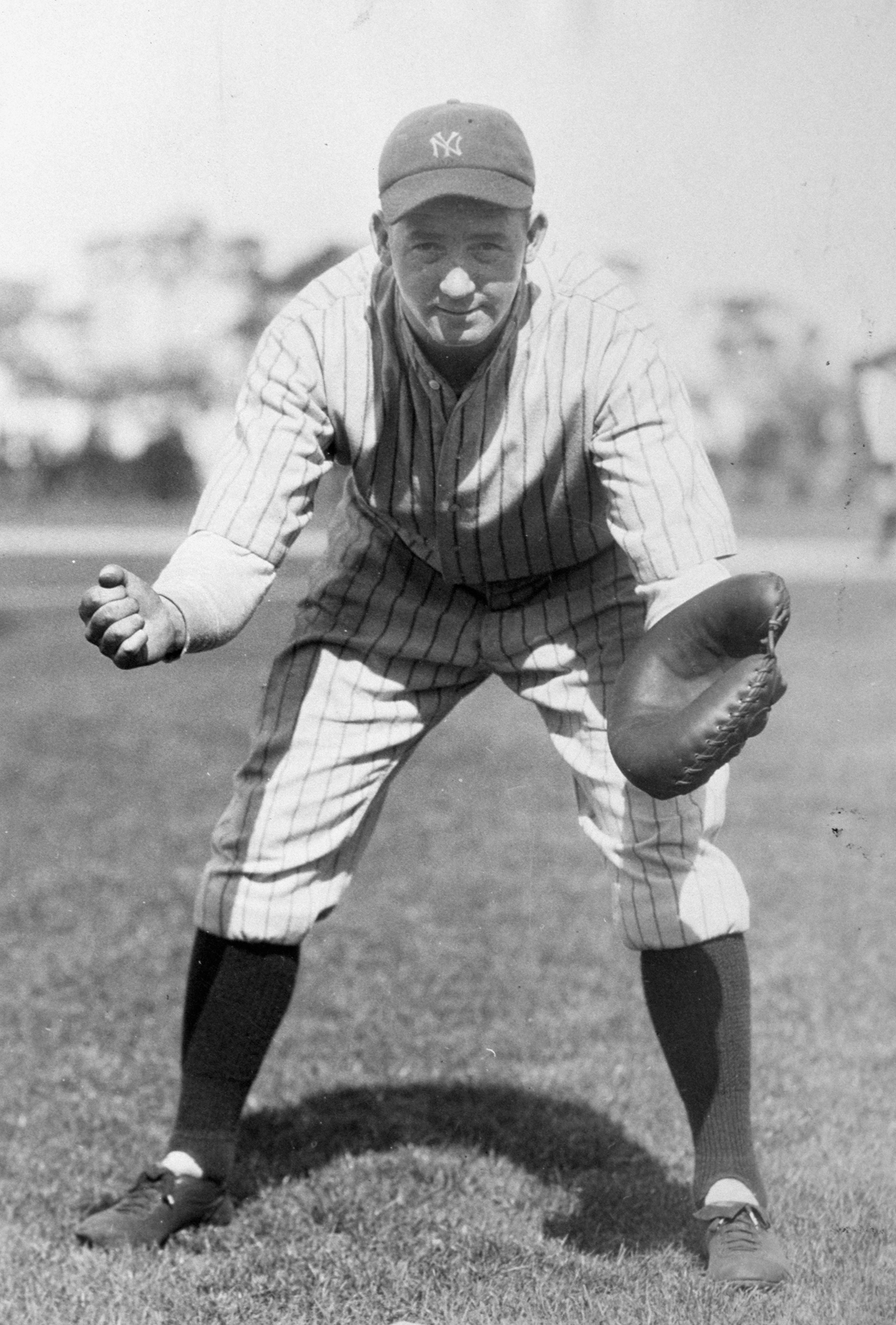

Photo credit: Johnny Grabowski, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Cort Vitty’s SABR Biography Project biography of Benny Bengough, Alan D. Gaff’s Lou Gehrig, The Lost Memoir (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), FamilySearch.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Statscrew.com, Baseball-Almanac.com and stathead.com.

Notes

1 Babe Ruth, “Babe Ruth’s Story in His Own Book of Baseball,” Paterson (New Jersey) Morning Call, February 9, 1929: 27.

2 See Rule 5.06(b)(3)(C) in the Official Baseball Rules, Office of the Commissioner of Baseball, 2024 Edition.

3 Alan D. Gaff, Lou Gehrig, The Lost Memoir (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 143. Statistics tabulated from the 1927 season by the author suggest Shocker’s preference mattered. In the 12 games he started with Grabowski behind the plate, he registered an ERA roughly one run lower (2.40 versus 3.38) as compared with his 15 starts paired with other Yankee backstops. Shocker was one of 17 major-league pitchers who were allowed to continue throwing spitballs after the pitch was banned in 1920. Jospeh Wancho, “Urban Shocker,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/urban-shocker/

4 “Electric City Immigrants: Italians and Poles of Schenectady, N.Y., 1880-1930, Chapter 1: Settlement,” Schenectady History website, https://www.schenectadyhistory.org/resources/pascucci/1.html, accessed June 23, 2024. One account that mistakenly claimed the Grabowski family moved to Schenectady in the mid-1910s asserts that they lived in Springfield, Massachusetts after leaving Ware. Ford Sawyer, “Johnny Evers Grabs Battery Mates from Minneapolis,” Boston Globe, August 16, 1924: 7.

5 Johnny was no longer listed as a member of the Grabowski household in 1920.

6 Schenectady earned the “Electric City” moniker from Thomas Edison’s Edison Machine Works, a manufacturer of electrical components that relocated its factory from the lower East Side of Manhattan to Schenectady in 1886 and later became General Electric.

7 “Johnny Evers Grabs Battery Mates from Minneapolis.”

8 Lauren Stanforth, “City sports legends honored,” Albany (New York) Times Union, February 5, 2008: D3; “Grabowski Leaves Today to Join the Minneapolis Club of American Ass’n,” Schenectady Gazette, March 2, 1921: 16. The author found no mention of Grabowski in the limited number of baseball game summaries published in local newspapers during the years in which he likely would have been in high school (1915-1918). One source erroneously lists Grabowski as attending Schenectady’s Mt. Pleasant High, a school that wasn’t constructed until 1931. Leo Trachtenberg, The Wonder Team: The True Story of the Incomparable 1927 New York Yankees (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1995), 160.

9 See, for example “I.P. Team is Loser to K. of C.,” Glens Falls (New York) Post-Star, June 21, 1920: 8, and “Box Score of Game Contested by A.C.,” North Adams (Massachusetts) Transcript, August 10, 1920: 8; “Mohawk Colored Giants (c. 1930’s),” Center for Negro League Baseball Research website, https://www.cnlbr.org/mohawk-colored-giants-uniform, accessed June 23, 2024. A barber with a passion for baseball, Bozzi resuscitated the Mohawk Giants in 1929, a team filled with Negro League superstars that had ceased operation in 1913 after owner William Wernecke fled with all the team’s money. The longtime centerpiece of Bozzi’s squad was former Homestead Gray William “Buck” Ewing. The Mohawk Colored Giants were arguably the most successful independent team in eastern New York during the 1930s.

10 “Johnny Evers Grabs Battery Mates from Minneapolis.” Based on author’s review of Senator box scores published in local newspapers. According to Grabowski, he attended a tryout with the Albany club that may have happened a year earlier. Randall Cassell, “Years as Yankee Grabowski’s Peak,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 2, 1941: 33.

11 “Whitehall and Union Bag Tie,” Glens Falls (New York) Post-Star, November 1, 1920: 3.

12 “Grabowski Leaves Today to Join the Minneapolis Club of American Ass’n.”

13 “All-Schenectadys Lose by One Point,” Schenectady Gazette, February 2, 1921: 12; “Cyclones Take Lead in Winter League by Berlin Stormers,” Schenectady Gazette, February 11, 1921: 18.

14 See, for example “Whirlwinds Tie Cyclones for Weather Lead,” Schenectady Gazette, January 12, 1922: 14, “Basketball Team at Hoosick Falls,” North Adams Transcript, November 5, 1925: 14. J, and “State League to Open Play in Fortnight,” Glens Falls (New York) Post-Star, November 17, 1926: 7.

15 “Camera Views of Millers at Kansas City Opener,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, April 17, 1921: 45; Earl Arnold, “Notes of the Millers,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, April 20, 1921: 10.

16 Earl Arnold, “Notes of the Millers,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, April 20, 1921: 10.

17 “Local Team Show Form,” Saskatoon (Saskatchewan) Star, April 28, 1921: 6.

18 “The Dope on the Hitters,” Saskatoon Star, August 12, 1921: 12; “A Good Grabber,” Saskatoon Star, May 7, 1921: 19; “Fielding Figures,” Saskatoon Star, July 26, 1921: 11.

19 Grabowski appeared in three games for the Millers, going 4-for-9 with a double. “Grabowski, Catcher, Will Join Pongs in Toledo, Minneapolis Morning Tribune, July 26, 1921: 10; Charles Johnson, “Millers Drop George and Grabowski,” Minneapolis Star, September 13, 1921: 8; “How Millers Hit,” Minneapolis Star, September 13, 1921: 8; Earl Arnold, “Millers Take Second Game in 10 Innings,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, August 31, 1921: 1.

20 The Schenectady Gazette mistakenly reported that Grabowski had been dealt to the American Association’s St. Paul franchise, whose team was also known as the Saints. “Jean Duval is ‘Holding Out’,” Schenectady Gazette, March 4, 1922: 16.

21 That group included World War I veteran Karl Adams, Alex McColl, who 11 years later, at the age of 39, made his major league debut with the 1933 AL champion Washington Senators and Hal Haid, a future member of two NL pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals teams.

22 “Grabowski Is Out of Game for the Season,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, September 17, 1922: 17. Grabowski went back home to a job with General Electric, a place he would work on and off during off-seasons for nearly two decades.

23 George A. Barton, “Nicollet Pickups,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, August 16, 1923: 15.

24 “Indian Scout Spends Day at Nicollet Park,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, July 18, 1923: 10.

25 George A. Barton, “Miller Huggins Seeks Grabowski,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, December 16, 1923: 35; “Crack Kelley Catching Corps,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, April 15, 1924: 21. The author did not uncover any mention in contemporary newspapers of Kelley rejecting the Yankee offer, but Grabowski’s presence on the Millers’ roster in the spring of 1924 makes clear that Kelley had done so.

26 George A. Barton, “Leo Magnum and John Grabowski Traded to Chicago White Sox,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, July 7, 1924: 10: George A. Barton, “French and Wirts May Make Their Debut with Millers Today,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, July 8, 1924: 16. Multiple accounts of the transaction published over the next few years made no mention of Comiskey sending Kelley another hurler. One retelling claimed Kelley netted “in the neighborhood of $50,000 in cash” from Comiskey, with another saying Comiskey paid $65,000 for the pair. Charles Johnson, “33 Players Go to Big Leagues in Late Years,” Minneapolis Star, June 26, 1926: 15; Ernie Phillips, “The Sport-O-Log,” Asheville (North Carolina) Times, December 26, 1927: 16.

27 Joe Hendrickson, “Always the Rush,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, May 26, 1951: 14.

28 “Grabowski to Catch,” Schenectady Gazette, October 17, 1924: 26. The most notable player on the team was future major-league doubles record-setter Earl Webb. Later a scout and then traveling secretary for the Yankees, McCorry is best known for persuading the Yankees to pass on Willie Mays in 1949, asserting that the young Birmingham Barons outfielder couldn’t hit a curveball. Allen Barra, Mickey and Willie: Mantle and Mays, the Parallel Lives of Baseball’s Golden Age (New York: Crown Archetype, 2013), 100.

29 Ford Sawyer, “John Grabowski,” Boston Globe, January 8, 1925: 21.

30 Former Chicago Cub star Frank Chance was hired to manage the White Sox after the 1923 season, but he developed a bronchial infection that left him unable to assume his duties at the start of the 1924 season, and ultimately took his life.

31 In the third of those four, on September 26, Grabowski went 3-for-5, including two doubles as Chicago dealt Boston Red Sox hurler Howard Ehmke, later star of the 1929 World Series, his 20th loss of the year. Six days later, in the last game Grabowski played in its entirety, he went 3-for-3 with a double off Cleveland rookie Carl Yowell.

32 Grabowski, Who Bucks Schalk, Has Toughest Job in Big Show,” Wilmington (Delaware) Commercial, March 18, 1926: 16.

33 At the start, I couldn’t get the ball over the plate,” Lyons recalled a quarter-century later. “I walked the leadoff batter in the first inning on four pitches so high that John Grabowski had to reach over his head to handle them.” Sam Greene, “Lyons Has tale,” Detroit News, August 5, 1951: 2-3.

34 “Eddie Collins,” Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1926: 8.

35 Several years later, the Minneapolis Star reported that the Yankees also gave Chicago $7,500 in the trade. “Connery Engineers Another Smart Deal,” Minneapolis Star, December 4, 1931: 27.

36 “Grabowski Must Reduce,” Berkshire (Massachusetts) Eagle, March 3, 1927: 15.

37 Hunt claimed that Grabowski’s “grocery warehouse … had increased to such an alarming degree that he cannot stoop to retrieve a bunt.” Marshall Hunt, “Yankees Totter into Detroit for Last Pennant Stand,” New York Daily News, September 27, 1928: 42.

38 “Did You Know That.”

39 Frederick G. Lieb, “Big Comeback Foreseen for Pirates: Pitching is Gretest Hazard of Yankees,” Washington Evening Star, April 6, 1927: 31; “Karpe’s Comment,” Buffalo Evening News, April 1, 1927: 33. According to Gehrig biographer Alan D. Gaff, “Pat’s biggest drawback was that too often his throws to second base ended up in the glove of center fielder Earle Combs.” Alan D. Gaff, Lou Gehrig, The Lost Memoir (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 143. Bengough stayed behind in St. Petersburg, Florida when the Yankees broke training camp in late-March.

40 Billy Evans, “One New Face Certain to be Seen in Game,” Pittsburgh Press, March 8, 1927: 30.

41 See, for example “Cobb and Grabowski in Action,” Schenectady Gazette, April 14, 1927: 22 and “Cobb’s First Time Up for Mack,” St. Joseph (Michigan) Herald-Press, April 14, 1927: 10.

42 Huggins was also even-handed over that span in how often he removed his starting catcher. Twelve times, Grabowski finished a game that Collins started, and eleven times Collins finished a game that Grabowski started. The constant changes didn’t seem to affect the pitching staff; for the year they led the league in WHIP (1.304), ERA (3.20), ERA+ (122) and walked fewer batters than any other team (409).

43 Through July 29, the Yankees won more often when Collins started, 39-10 versus 32-17-1 in Grabowski’s starts, but, as tabulated by the author, New York’s starting pitchers registered an ERA that was 0.35 lower in Grabowski’s starts (2.94 versus 3.33).

44 “Grabowski Out, Huggins After New System,” New York American, July 30, 1927: 9.

45 “Injured Hand Again Benches Grabowski,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 27, 1927: 12; “Grabowski Returns,” Schenectady Gazette, September 21, 1927: 23.

46 “2,500 Fans Will Honor ‘Nig’ and Make a Large Gift at Yankee Stadium,” Schenectady Gazette, June 25, 1927: 14.

47 “Grabowski Grabs $1300,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 1, 1927: 17.

48 “Years as Yankee Grabowski’s Peak.”

49 “1927 Yanks All-Time No. 1 – Except in Pay,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1952: 13; “Players Will Split Largest Series Purse,” San Francisco Examiner, October 9, 1927: 36. Grabowski presumably applied some of his World Series winnings toward his purchase of a new 1927 REO Flying Car. “‘Likes ‘em Fast’,” Scranton Republican, November 18, 1927: 18; “1927 REO Flying Cloud,” Classic Auto Mall website, https://www.classicautomall.com/vehicles/2489/1927-reo-flying-cloud, accessed June 26, 2024.

50 “Yankee Battery Here Today,” Schenectady Gazette, October 15, 1927: 14.

51 “Lou at Dorp Tonight,” Saratoga Springs (New York) Saratogian, February 4, 1928: 11; “Gehrig Five is Defeated by 6 Points,” Schenectady Gazette, February 6, 1928: 12; Adrian Garro, “Watch new footage from a 1927 barnstorming exhibition game featuring Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig,” Cut-4 MLB website, November 27, 2018, https://www.mlb.com/cut4/babe-ruth-and-lou-gehrig-footage-from-1927-c301173748. The Stars shared a name with the baseball team that Gehrig headlined during his fall 1927 barnstorming tour with Ruth.

52 James C. Isaminger, “Macks Divide with Yanks, Protesting Second Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 31, 1927: 22. Five years later, sportswriter, and later Commissioner, Ford Frick recounted how Grabowski had to fight his way back onto the field through a crowd of A’s who’d “rushed to his aid.” Ford Frick, “Ford Frick’s Broadcast!”, New York Evening Journal, May 26, 1932: 28.

53 Marshall Hunt, “Bam’s 14th Gives Yanks Split,” New York Daily News, May 31, 1927: 31; “Mack Protest Disallowed by Prexy Johnson,” San Francisco Examiner, June 12, 1927: 68. In anouncing his decision, Johnson cited an existing rule that addressed balls thrown or dropped into a dugout as the basis, consistent with the logic the game’s umpires had applied, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. Contemporary accounts of the play give no indication that Grabowski dropped the ball. “Macks Divide with Yanks, Protesting Second Game.”

54 “Umps Rule Out Scoring on Spill,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 21, 1928: 22. In describing the new rule, the Cleveland Plain Dealer mistakenly reported that Huggins rather than Mack filed the protest over the play’s outcome.

55 Chet Youll, “Karpe’s Comment,” Buffalo Evening News, March 22, 1928: 29.

56 Thomas Holmes, “Wilson Better Than Yankee Catchers if Not Worn Out,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 29, 1928: 10.

57 A few months after the season ended, Grabowski claimed he didn’t hit well “because Huggins made him choke up.” “Did You Know That,” Bayonne (New Jersey) Times, February 16, 1929: 8.

58 James C. Isaminger, “Simmons Slaps Home Run with Three on Sacks,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 28, 1929: 1S.

59 “Six Yankee Players Get Rest with Pay,” Paterson Morning Call, September 23, 1929: 17. During his time on the bench, Grabowski appeared in at least one exhibition game, in Buffalo. W.S. Coughlin, “Gehrig Subs for Babe, Autographs Four Swats, Baseballs; Nekola Hurls,” Buffalo Courier Express, July 23, 1929: 14.

60 See, for example, “Blues Slug Out 7 to 5 Victory Over Colonels,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, August 3, 1930: 17.

61 Tommy Fitzgerld, “Five Colonels are Selected; 12 Men Named,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 23, 1930: 11.

62 John Grabowski and Frank E. Nicholson, “Favorite Jokes of Famous Folk,” Paterson Evening News, May 5, 1931: 7.

63 “Catcher Better Off Not to Give Pennock ‘Sign’.”; Jimmy Powers, “The Power House,” New York Daily News, May 26, 1941: 42.

64 J.E.C., “Catcher Better Off Not to Give Pennock ‘Sign’,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, March 22, 1939: 12. The day after grounding into a ninth inning twin-killing with two runners on in Chicago on August 27, 1925, Ruth was fined $5,000 and suspended by Huggins for a variety of offenses. Grabowski’s tale implied that he was catching at the time, but he did not appear in that game. He also erred in some of the game’s finer details, putting it in 1924 rather than 1925, with Chicago up 2-1, rather than 6-5.

65 Grabowski Goes Back to the American Loop; Sold to Detroit Team,” Schenectady Gazette, November 27, 1930: 19; “Saints Sell Infield Star to Cincinnati,” Sioux Falls (South Dakota) Argus-Leader, September 13, 1931: 9.

66 Harry Bullion, “Team is Stronger at Every Position,” Detroit Free Press, March 15, 1931: 17. In 1930, Detroit led the majors in stolen bases (109) and passed-balls (17), and finished last in the AL in throwing out base stealers (31 percent). The un-named center field replacements were presumably rookies Hub Walker and Gee Walker, who started over 90 games combined in center for Detroit in 1931.

67 “Tiges Beat Cleveland,” Detroit Free Press, August 6, 1931: 15; Bill Lamb, “Pete Appleton,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Pete-Appleton/

68 SABR biographer David E. Skelton claims that Susce was involved in 37 fights during his first six years of his baseball career. In 1946, Susce came out ahead in a battle that Grabowski tragically lost. Nine months after Grabowski died from burns he suffered in a house fire, Susce had to rush his family out of their Pittsburgh home when it caught fire from an overheated furnace. David Skelton, “George Susce,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/George-Susce/

69 “Toronto Rallies in 9th to Down Royals by 4-3,” Montreal Gazette, August 31, 1933: 12; “Red Munn is Signed,” Montreal Gazette, September 1, 1933: 14.

70 C.E. McBride, “Sporting Comment,” Kansas City Star, August 25, 1934: 5.

71 “Get the Name, Then His Job on Team,” Buffalo Times, February 13, 1921: 45.

72 D.A.L. MacDonald, “Sports on Parade,” Montreal Gazette, March 14, 1936: 14. The story may have been true but not the circumstances; Smolley, Grabowski and Buzz Arlett were supposedly enjoying an off-day from playing for the San Francisco Missions. Smolley played for the Missions from 1926 through 1929, but Arlett played across the bay in Oakland and Grabowski never played for any California team.

73 Paul Gallico, “It Was THAT Hot,” New York Daily News, July 10, 1928: 28. Invented in 1891, air-filled chest protectors were used by major-league backstops into the 1930s, and by umpires for another two decades. In a later re-telling of Gallico’s tale, Grabowski lands in Ireland after encountering cooler weather there. Marc T. McNeil “About an Ex-Catcher and an Ex-Sports Writer,” Montreal Gazette, April 30, 1941: 16.

74 D.A.L. MacDonald, “International League News and Gossip,” Montreal Gazette, August 26, 1935: 14; Paterson Morning Call, September 11, 1935: 20. The man who hired Grabowski was International League vice president, and future NL president, Warren Giles.

75 Walter Gilhooly, “In the Realm of Sport,” Ottawa Journal, July 11, 1936: 23; “Canadian-Amer. League,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1936: 8; Joe Polakoff, “Football at Taylor High?”, Scranton Tribune, November 14, 1937: 25.

76 “’Nig’ Grabowski New Eastern League Umpire,” Hartford Courant, March 31, 1938: 52. In late May 1940, Grabowski was fired for reasons never reported, only to be reinstated by the end of June. “Grabowski Released by Eastern,” Springfield News, May 28, 1940: 2; Les Stearns, “Real Story is Yet to Be Told,” Springfield Evening Union, June 3, 1940: 16; “George Holds Triplets to 3 Blows, 3-0,” Scranton Tribune, July 1, 1940: 15.

77 Charles Young, “Grabowski Signs to Umpire in Eastern League,” Albany Knickerbocker News, March 9, 1938: 21; Charles Young, “Umpire Grabowski is ‘No Homer’,” Albany Knickerbocker News, May 6, 1940: B-7.

78 Charles Young, “Barlik Called Greatest Young Umpire,” Albany Knickerbocker News, June 21, 1939: 6-B. For example, a few weeks earlier, Grabowski had gotten diminutive Albany Senators manager Rabbit Maranville hot under the collar when he insisted that a game proceed during a rain shower. “Another Reason Why a Uniform Rule is Needed,” Scranton Tribune, May 24, 1939: 14.

79 “Richardson Send Ump to Int. Loop,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times Leader Evening News, September 10, 1940: 18; “Van Graflan Gets Assignment for Red Wing Opener,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 16, 1941: 23.

80 “So They Say,” Holyoke (Massachusetts) Transcript-Telegram, June 27, 1944: 10. The Montreal catcher was former AL backstop Wid Matthews. Sukeforth’s claim to fame is that he was Jackie Robinson’s first major league manager, serving as the Brooklyn Dodgers interim manager to start the 1947 season until a replacement was hired for the suspended Leo Durocher, a Yankee teammate of Grabowski’s.

81 “Years as Yankee Grabowski’s Peak.”; “Briefs from the Baseball Leagues,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 23, 1942: 5. Grabowski probably learned the trade working off-seasons at General Electric, which he did dating back to at least 1922. “Grabowski Is Out of Game for the Season,” St. Joseph Gazette, September 17, 1922: 17.

82 “Rosie’s Round-Up,” Bayonne Times, June 2, 1942: 8. American Locomotive’s Schenectady plant turned out all of the roughly 1000 M-7 tanks that routed German and Italian tank divisions under the command of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in the North African Battle of El-Alamein, fought during the fall of 1942. “American Locomotive Company (Alco or ALCO) in World War Two,” USA Auto Industry in WWII website, https://usautoindustryworldwartwo.com/alco.htm, accessed June 28, 2024.

83 “Necrology,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1946: 32.

84 “John Grabowski Expires of Burns,” Troy (New York) Times Record, May 23, 1946: 15. Grabowski’s death certificate listed second degree burns to his face, neck, back, hands, arms and both feet. New York State Certificate of Death, Johnny Grabowski file, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

85 Ray Canton, “Yanks of ’27 Would Run Away from Present Clubs – Meusel,” Los Angeles Mirror, January 24, 1950: 56.

86 “1 Killed, 7 Injured When Auto Jumps Over Embankment,” Buffalo Courier, May 19, 1924: 2; “Holyoke Man Killed near Canadian Border,” Springfield News, June 1, 1931: 25; “Grabowski Rites Monday; Bank Retiree,” Schenectady Gazette, February 19, 1983: 21.

87 Lauren Stanforth, “City sports legends honored,” Albany Times Union, February 5, 2008: D3.

Full Name

John Patrick Grabowski

Born

January 7, 1900 at Ware, MA (USA)

Died

May 23, 1946 at Albany, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.