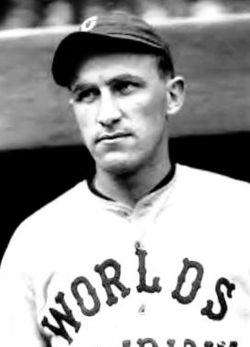

Bill Wambsganss

Contemporary accounts of Cleveland second baseman Bill Wambsganss’ fielding almost universally used the word “slick” to describe his play. Ever since his final year in the majors, 1926, he’s largely been remembered as the man who pulled off the only unassisted triple play in World Series history but he was also an important member of that 1920 world championship team and a ballplayer who stayed active in baseball in many ways, from managing in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League to working with indoor baseball and youth baseball.

William Adolph Wambsganss was a Cleveland native–born in the area that has since 1930 been known as the city of Garfield Heights–and lived to be 91 years old (March 19, 1894–December 8, 1985). He was right-handed with a playing height of 5-feet-11 and a listed weight of 175 pounds. During his years in baseball, he was more typically known as Wamby.

A Lutheran clergyman named Philip Wambsganss, age 36, born in Bavaria, is found in the 1860 Census, living in Root Township, Indiana, as was Elizabeth Wambsganss, one year younger and listed as a house maker. The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, assembled at Case Western Reserve University, however, states that Bill Wambsganss’ parents were Philip and Carrie (Shellman) Wambsganss and that he was born in what is now the city of Garfield Heights.

The Wambsganss name was German in origin, though the best a German professor at Concordia College in Fort Wayne, Indiana, could tell him was that it seemed to combine components of the word for overcoat, or at least a word that might have been used as overcoat in early 20th century German usage. Bill said, “I don’t know whether it fits me or not, but I have worn it all my life and will probably carry it with me to the end.” Not everyone in the family wore it as well. Bill’s wife had it listed as “Wamby” in the telephone directory. William Adolph Wambsganss Jr., took on the last name of Wamby, as did Bill Wamby III. Apparently another grandson named Robert preferred the most historic last name. [Christian Science Monitor, February 17, 1964, and The Sporting News, April 2, 1984] Another grandson, Michael, uses the surname Wamby and understands the family to have originated in the Alsace-Lorraine region. [E-mail from Michael Wamby, July 11, 2011]

Wambsganss was a tongue-twister of a name, and didn’t easily fit into newspaper boxscores–though some editors made the effort. He was W’ganss, Wam’g’ss, Wambs’s, W’bsg’ss, and any number of other renditions. In Cleveland, though, the nickname Wamby was more or less formally approved, he told The Sporting News, when the scorecard printing company at League Park asked him if they could shorten it. “It was Bang & Bigley, and they operated a shop under the stadium. This fellow Bang — he was the brother of Ed Bang, a longtime Cleveland sports editor — stopped me when I went through the gate one day and asked if it would be OK if they shortened me to Wamby, so the name would fit better on scorecards. I told him I thought it sounded pretty good.” [The Sporting News, April 2, 1984]

The Bang in question was Charlie Bang, and it was his brother Ed, the writer, who informed baseball fans of some of the details of Bill’s early life. When Bill was a bit less than two years old, his parents moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana. At first, Bill had thought of following in his father’s footsteps. Reverend Wambsganss was indeed a Lutheran minister and enrolled his son at Concordia College. Bill also studied for a while at a seminary in St. Louis. He graduated in 1913 but really enjoyed playing second base on the school’s varsity baseball team. His idol growing up was Indians second baseball Nap Lajoie. [The Sporting News, February 27, 1924]

Bill became what some called a reverse Billy Sunday–a minister-become-ballplayer, rather than the other way around. Bill’s father wasn’t the least upset. A true baseball fan himself, he urged his son to pursue the calling to play ball.

Bill spent his first year in the pros, 1913, with the Cedar Rapid Rabbits of the class D Central Association, playing shortstop and batting .244 in 67 games. His second year with Cedar Rapids, he played in 84 games and started hitting distinctly better, at .317. He was almost part of baseball history on July 10 as Rabbits pitcher Lefty Mellinger threw a no-hitter against Burlington, marred only by an error when his first baseman unaccountably dropped a “perfect throw.” The man who reached base was promptly retired on a double play.

As the season progressed, the Cleveland Naps wanted the hometown hitter. Owner Charles Somers bought him from Cedar Rapids on August 1, for a reported $1,250. Manager Joe Birmingham first put him in a game against the Washington Nationals on August 4, replacing Ray Chapman at shortstop late in the game. Batting in the bottom of the ninth, after Cleveland had come within two runs of Washington, Wambsganss grounded a ball to Wally Smith, the second baseman, and a run scored when Smith misplayed it. With two outs and the bases loaded, Joe Wood smoked one to second and this time Smith held onto the liner.

Wamby’s first start, on August 10, 1914, resulted in an 0-for-2 at the plate. He picked up his first hit, a single, on the 11th. His first big game was on August 16; he went 2-for-5 with a double, and helped execute two double plays. On September 30, he tripled in the bottom of the 12th (he had doubled earlier) and scored the winning run on Nemo Leibold‘s single, beating the White Sox, 6-5. That first year, as an understudy for Chapman, he appeared in 43 games, batting .217 and driving in 12 runs. He also filled in during four games for his childhood hero, Nap Lajoie, the baseball legend after whom the team was known. The Naps finished in last place, and even right fielder Shoeless Joe Jackson had a down year — hitting only .338.

In January 1915, Lajoie was sold to the Philadelphia Athletics, opening up the second base position. The Cleveland team, renamed the Indians, climbed one notch in the standings, to seventh place, but were 44½ games behind the first-place Red Sox. Wambsganss had an even more anemic bat (he hit .195 for the season, driving in 21 runs) but was valued for his slick fielding–now primarily at second base–and appeared in 121 games. He played in 35 games at third base, too. There were some remarkable games, notably the July 27 game against Washington in which Cleveland got one hit and Washington two–and Washington won thanks to Clyde Milan‘s steal of home in the first inning.

The day before the 1916 season began, the Red Sox traded one of their biggest stars, Tris Speaker, to the Indians for Sad Sam Jones, $55,000 in cash, and Boston’s choice (to be made within 10 days) of either Bill Wambsganss or infield prospect Fred Thomas. The Red Sox made the wrong choice. Indians manager Lee Fohl wanted to keep Wamby, so he benched him in favor of Joe Evans in order that the Red Sox scouts couldn’t get a good look at him. The ploy paid off, and after the Sox selected Thomas, Wamby was in the lineup and off to a hot start. Ray Chapman had suffered a number of injuries, so Fohl inserted Wamby at shortstop–he appeared there in 106 of his 136 games, and boosted his batting average to .246, with 45 runs batted in. Slick he may have been in the field, but there were days that were worse than others. On June 8, his first-inning error on a play that could have retired the side opened the gate for five Washington runs, the only ones the Senators scored; the game ended with a 5-5 score after 14 innings. Wamby’s stats might not look like anything special, but his play was highly regarded. A Washington Post look ahead to 1917 wrote of manager Fohl, “He looks for Wambsganss to be even more of a sensation than he was during the last campaign.” [Washington Post, December 12, 1916]

Wamby was, at the very least, steady in 1917. He bumped his average up a bit, to .255. Everything else stayed very much the same, except that Chapman reclaimed shortstop and Wamby played almost the whole season (137 games) as the second baseman. The two working together–Wamby and Chappie–were considered perhaps the best double-play combination in the league, but the one time Wambsganss made a major headline in the national press was due to an error that was said to cost an 8-2 loss to the White Sox. WAMBSGANSS TRIPS ON NAME read the Los Angeles Times headline on June 21. He made two errors in the same game on June 5–showing terrific range, getting to balls, and then making errant throws–“trying to do too much,” commented the Boston Globe. Ten days after he purportedly tripped on his name, he walked down the aisle and married Cleveland-born Effie Mulholland. They set up house in Lakewood, Ohio, near Cleveland, and raised a family–daughter Mary, son Bill Jr., and another daughter, Lois.

With the United States now in the World War, no one knew how the 1918 season would wind up, or whether it would be curtailed. The season was brought to a halt at the beginning of September, and for the third time in four years, Boston prevailed in the pennant race and won the World Series. On July 5 Wambsganss received his orders to report to Camp Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky. His last games were the two of the July 21 doubleheader against Philadelphia, in which he went 3-for-5 with two stolen bases and two runs scored in the first game (3-2, Cleveland in 11 innings) and 1-for-3 in the second (a 5-5 tie after eight, called so that both teams could catch the train).

Wamby left behind a .295 season average with 40 RBIs in just 87 games. He did very well in the Army, too, advancing to officers training camp at Camp Gordon in Georgia (in the process depriving the Camp Taylor baseball team of one of its best players). In 1919, with the war over, Lt. Wambsganss was back with Cleveland in time to put in a full 139-game season.

Bill had one of the best days of his career on May 18, 1919, going 4-for-4 against the visiting New York Yankees, three singles and an inside-the-park home run off George Mogridge which escaped the clutches of Ping Bodie and brought in the final three runs of the 4-3 win. It was his first career home run. He added a second homer on August 15, off Washington’s Jim Shaw, but in a losing cause. May was a good month overall, with Wamby batting .407 as of May 24, well ahead of Joe Jackson’s .386, but the season ended with Wamby hitting .278 (and driving in a career-high 60 runs) while Jackson hit .351 for the champion White Sox–a year later to become known as the Black Sox. Once again Wambsganss led the league in errors, with 30. One of them he was glad to take. It came at the Polo Grounds in the seventh inning of Ray Caldwell‘s September 10 no-hitter against the Yankees. The New York Times account called it an “easy roller,” in fact “such an easy affair that Wamby should have got it by one hand with his eyes closed. He ran in on the ball and then let it trickle through his mitts.”

That 1920 season was the year in which “Wambsganss” eventually became, if not a household name, well-known in the world of people who’ve learned unusual facts about baseball. It’s not always players themselves who know the game. In 1949, Philadelphia A’s pitcher Joe Coleman was speaking at a community event in Northampton, Massachusetts, and was asked whether or not anyone had ever made an unassisted triple play in the World Series. He had to admit he didn’t know–but Grace Coolidge, the former First Lady of the United States, quietly replied, “Yes, Bill Wambsganss, Cleveland infielder, in the 1920 Series.” [New York Times, November 12, 1948]

It was also the year in which Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman was killed at home plate, struck by a Carl Mays pitch on August 16. The two had worked so hard at perfecting the double play that Ray once told the second baseman, “Bill, you’re the only second baseman I’ll ever play next to.” [Mike Sowell, The Pitch That Killed, p. 101]

Of course, to get to the World Series the Indians first had to win the pennant. It was a three-team battle, with Cleveland on top, two games above the White Sox and three ahead of the New York Yankees, still pennant-less in the history of the franchise. For Cleveland, it was their first pennant. The Indians clinched it with a 10-1 win on October 2, a quickly-played (1:28) game that saw Wambsganss go 3-for-6 with two runs scored. He helped execute two double plays and might have had another hit except that he was struck by his own batted ball in the fourth and therefore ruled out.

Player-manager Tris Speaker led the club with a .388 average and 107 RBIs. Ex-Red Sox third baseman Larry Gardner drove in 118 and batted .310. Catcher Steve O’Neill hit .321. Wamby was one of only two position players to hit under. 300 (the team average was .303), and he was way under .300, finishing a disappointing season batting just .244. It was the only year in a nine-year stretch in which he didn’t achieve double digits in stolen bases. Wamby’s 36 errors led all second basemen in that category, but he was nonetheless a key cog in the Cleveland lineup. Three years later, Francis J. Powers, writing about Wambsganss in The Sporting News, observed something about his relationship to the team’s performance: “It is a strange coincidence that when Bill does have a bad day the whole team goes to pieces.” [The Sporting News, July 5, 1923]

And he had a very difficult time trying to deal with the death of his double-play partner.

The Series itself was full of milestones. Cleveland played the Brooklyn Robins, who had taken the National League with ease. Among other things, the Series would pit Brooklyn third baseman Jimmy Johnston against his two-year-older brother, Cleveland first baseman Doc Johnston. Jimmy hit .291 during the regular season; Doc hit .292. Neither played any significant role on offense in the Series.

Wamby was 0-for-3 in Game One, 0-for-3 in Game Two, and 0-for-3 in Game Three. It was a best-of-nine Series; Cleveland won the first game but Brooklyn beat them in the next two. Some Indians fans were starting to get down on Wambsganss. For his part, he apparently confided in F.C. Lane, the editor of Baseball Magazine, that he was still really struggling with the loss of Chapman. In Game Four, Wamby got going with a first-inning walk and scored the first run of the game, a 5-1 Indians win. He led off with a single in the third and scored again, and singled again, driving in the Indians’ fifth run of the game, in the sixth.

Game Five, on October 10, was a day for headlines. The public awoke that Sunday morning to read that Brooklyn pitcher Rube Marquard had been arrested, charged with scalping tickets before Saturday’s game. Turned loose so he could make the game (the Cleveland chief of police said it would “hardly be sportsmanlike” to hold him), Rube threw three innings in relief, giving up two hits but no runs. His manager, Wilbert Robinson, “was so provoked when he heard of Marquard’s arrest he is alleged to have said he would not give five cents to get him out of hock.” [Boston Globe, October 10, 1920] After Marquard was found guilty on October 12, Brooklyn severed all ties with him. So did his wife, who divorced him within the week.

In Game Five, Wambsganss singled in the first and was the second of four runners to score on right-fielder Elmer Smith‘s grand slam. One might have expected Smith to grab all the headlines; it was the first grand slam in World Series history. Then pitcher Jim Bagby homered, a three-run shot in the fourth inning, perhaps pushing for his own headline–it was the first home run by a pitcher in a World Series. The score was 7-0 Tribe after four innings, and things were looking good for Bagby, who’d lost Game Two but was 31-12 (2.89 ERA) in the 1920 regular season.

Bagby got himself in trouble in the top of the fifth, though, allowing back-to-back singles to second baseman Pete Kilduff and the catcher, Otto Miller. Kilduff held up at second. Two on, nobody out, and Mitchell was up–Clarence Mitchell, the left-handed reliever who had taken over for Brooklyn starter Burleigh Grimes. The Indians had two men warming up in the bullpen.

Mitchell was a decent hitter and Robinson had used him occasionally to pinch-hit. Wambsganss deliberately played back on the outfield grass, as Mitch often hit to right and Wamby wanted to keep the ball from getting through and perhaps scoring a run. When the count reached 1-1, the hit-and-run play was put on, and it had everything to do with the execution of the play that followed. Mitchell hit the ball hard, and it was heading toward center field several feet to the right of second base. Wambsganss had broken toward the bag, or he wouldn’t have been able to make the play. Make it he barely did, catching the ball in mid-flight with his outstretched glove. Kilduff was almost to third base and Miller rapidly approaching second. Momentum carried Wamby in the direction he was going and two or three strides took him to second base. The minute his foot hit the bag, Kilduff was out. And Miller’s own momentum brought him right to Wamby. He pulled up short and didn’t have time to turn back and try to retreat. He was just five feet away. “He stopped running and stood there, so I just tagged him. That was all there was to it,” Wambsganss explained. “Just before I tagged him, he said, ‘Where’d you get that ball?’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve got it and you’re out number three.’” It was all over in a flash. Three outs. There was dead silence in the park as everyone took in what they’d witnessed, and then an explosion of celebration. [The Wambsganss quotation comes from The Sporting News of January 22, 1966.]

Mitchell came up again as the second batter in the top of the eighth. There was a runner on first base and nobody out. Wamby watched as Mitchell grounded into a 3-6-3 double play. Two times up, five outs.

There was no guarantee that Cleveland would win. Jim Bagby gave up 13 hits that day, so the defense was very much a key. The Indians won the game in the end, 8-1, and took the next two as well. They were the world champions.

In recognition of their feats, Mayor Fitzgerald of Cleveland presented both Smith and Wambsganss diamond-studded medals before Game Six. (The Washington Post reported that the medals were given to Elmer Smith and Phil Wambsganss.) Wamby was 0-for-4 in Game Six and 1-for-4, an inconsequential single back to the pitcher in the third inning, in Game Seven.

The only other unassisted triple play in the still-young 20th century was also executed by a Cleveland player, Neal Ball, against the Red Sox in 1909, during a regular season game in Cleveland. Tris Speaker was the only player to have witnessed both.

After the Series, Wamby and five other Indians left for a deer-hunting trip in Pennsylvania. He’d hit .154 in the Series, but had a fielding percentage of 1.000, with 21 putouts. The three all made on the same play ensured that his name would go down in history.

On the day that Wamby pulled off the triple play, crowds gathered in front of newspaper offices around the country. These were the days before radio broadcasts of games, and the notion of television was pure science fiction. Play-by-play results were telegraphed to newspapers and conveyed to those gathered in front of the newspaper offices, sometimes by way of elaborate scoreboards erected for the occasion. In Fort Wayne, the Journal Gazette had set up a magnetic board that was being operated by sports editor Bob Reed. He knew that Rev. Wambsganss was in the crowd of several thousand people on the streets out front. When Reed received word of Wamby’s triple play, he said, he was stunned, then nervous. “Finally, I grabbed a megaphone and shouted the news. The roar which followed was the loudest I had ever heard. What a thrill that was–home town boy making a play like that!” [Chicago Tribune, January 13, 1955]

Arthur Daley of the New York Times said one other event of note occurred that day. “Prohibition agents put the arm on [Brooklyn owner] Charlie Ebbets because that soft-hearted gentleman took pity on chilled reporters and gave them nips from his pre-Prohibition stock.” [New York Times, September 22, 1955]

Riggs Stephenson seemed to offer some real competition for Wamby at second base in 1921, but Bill overcame a broken arm suffered early in the season and stepped it up at the plate when he came back, hitting .285, driving in nearly as many runs as he had the previous year, and scoring only three fewer despite being in just two-thirds as many games. The team average climbed to .308. The Yankees won the pennant by 4½ games over the Indians.

In both 1921 and 1922, Wambsganss led the league in sacrifice hits (43 and 42, respectively). He was a particularly good bunter, often reaching first safely. In 1921, Bill batted .285, and he hit .262 the following year. He drove in 47 runs each of the two years.

A broken finger on July 1 cut a couple of weeks out of the middle of the 1923 season, but he still appeared in 101 games and hit for an average of .290, driving in 59 runs. He cut back dramatically on his strikeouts, whiffing only 15 times while drawing 43 walks.

An early January 1924 look ahead in The Sporting News saw Wamby inked in at second, with no other Indian competing for the job. By the time the paper reached readers, though, he had been traded to Boston on January 7. The trade reunited him with manager Lee Fohl, now skipper of the Red Sox. Wamby was disappointed not to be playing for his home team any longer, but philosophical about the change. “It’s the fortunes of ball,” he said. “I have always liked Lee Fohl and Boston and they tell me I am going to like Bob Quinn [the Red Sox owner], too, so I have no cause for complaint.” [The Sporting News, February 27, 1924] The trade was a seven-player transaction sending Steve O’Neill, Dan Boone, and Joe Connolly to Boston with Wambsganss, for George Burns, Roxy Walters, and Chick Fewster.

Wamby was now playing against Tris Speaker again, but with the two teammates having swapped the uniforms they’d originally worn as rivals. Speaker was with Cleveland, and in his sixth year as player-manager. Wamby was now with the Red Sox, where Speaker had played against him in 1914 and 1915. Wamby played well, appearing in 156 games and participating in an even 100 double plays. He hit .275 (the team batted .277), and he and Steve O’Neill were credited with being “responsible, in large measure, for much of the improvement in the team. …Wamby’s hitting has actually become fierce. And his steadying, stabilizing influence in the infield is invaluable in measuring team values.” [The Sporting News, May 29, 1924] The hitting tailed off, and Wamby’s 30 errors led the league at his position. The Red Sox did rise out of eighth place, and finished only a half-game behind the sixth-place Indians.

The Sox switched their spring training from San Antonio to New Orleans in 1925. Bill Wamby was one of the later arrivals due to a trick knee that gave rookies Billy Rogell and Bud Connolly a chance to shine at second base in the early exhibition season. Well into May, Wamby was hitting up a storm and “playing a whale of a game,” in the words of Boston sportswriter Burt Whitman, driving in eight runs in a four-game stretch, with the 4-for-4 game on May 9 seeing his average reach .380. It was all downhill from there, though, with an 0-for-6 game on May 18 plunging him from .310 to .289. He never reached .300 again and tailed off to .231 by the end of the year. Even with a team as bad as the Red Sox were, they thought they could do better. Francis J. Powers was a bit premature, though, writing in the November 12 Sporting News that Wamby was “on the lookout for an assignment as he … is out of the big leagues.” He’d been placed on waivers and no one claimed him, but the Red Sox still held rights to his contract. They cashed in when the Athletics picked him up on December 12 for the $4,000 waiver wire price.

But 1926 was Wamby’s last year as a major leaguer. He didn’t see much duty, except in the pinch, appearing in 54 games but only in 25 of them as a fielder and even then handling only 48 chances. He batted .352 and scored 11 times — though he drove in only one run. After the season was over, Connie Mack worked a deal that sent Wambsganss to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association with Joe Hauser on option and paid $50,000 on top of that, all to acquire minor league prospect Dud Branom, whom Mack coveted. The deal was a dud, to say the least; Branom had only 94 big-league at-bats, hitting .234 lifetime.

Wambsganss still had a lot of baseball in him, and played seven more seasons of minor-league ball. At the time he was dealt to Kansas City, it was foreseen that he might become the manager of the team. [The Sporting News, December 16, 1926] That didn’t come to pass, but he put in three good seasons in Double-A for the Blues.

Questions were raised about how long Wamby’s legs would hold up after his 1927 season–though one wonders why, since he batted .307 and was said to have saved or won at least five games with his pinch-hits. In May 1928, he was said to be playing with a new zest for the game but as the season wore on, his legs did seem to weaken. In a year-end wrapup in November, Wambsganss was said to be “short-winded” and to have shown trouble with his legs if playing on a regular basis, but dangerous if used sparingly as a pinch-hitter. [The Sporting News, November 15, 1928] He hadn’t been used that way at all; he accumulated 637 at-bats and hit .298.

It was in 1929 that he was cut back. His average stayed about the same, .295, but he had only 359 at-bats. The Sporting News correspondent from Kansas City assessed his contribution: “Wamby has reached the age where he can not go at top speed for a long stretch, but he can make the youngsters look silly for two or three weeks.” [The Sporting News, September 12, 1929] Wamby also worked as a coach for the Blues. Before the year was out, the New Orleans Pelicans in the Single-A Southern Association purchased his contract from the Blues. He didn’t play much either for the Pels or for the Louisville Colonels, when he returned to Double-A in midseason. He hit .209 in 43 at-bats for New Orleans, coaching for the Pelicans, and .091 in 22 at-bats for the Colonels. It looked like the end of the road as a player, and Wamby became a free agent at the end of the season.

In 1931 the Springfield, Illinois, club of the Three-I League asked Kansas City to run the team for them, and Kansas City reached out to hire Bill Wambsganss as the manager. When he talked with reporters, he said he intended to play second base as well. As it transpired, he put himself into only eight games, at a time that a couple of his players were hurt. He made seven hits in 18 at-bats (.389) but it wasn’t the active season he’d anticipated. He did well as skipper, leading the team to a pennant. One of his players was Elmer Smith, who hit the grand slam in the same game in which Wamby had pulled off the triple play. [Mark McGuire and Michael Sean Gormley, Moments in the Sun, p. 192]

Even before the 1931 season began, Wambsganss had started taking a course in journalism with an eye toward finding work in the world of newspapers. For a few weeks at least in the late fall and early winter of 1934, his column “Character Sketches,” in the pages of The Sporting News (see, for instance, November 19, 1931), presented well-written looks at some of the players, umpires and others in the game.

In 1932, Wambsganss took the reins of the Fort Wayne Chiefs, a Class B Central League team. They came in second overall, but took first place in the second half of the split season. Bill hit .211 with three singles and a double in 19 at-bats. The Chiefs were swept four games by Dayton in the playoffs; Springfield had lost the 1931 playoffs in six games.

Wambsganss’ parents continued to live in Fort Wayne, but he and Effie maintained their home in Lakewood. For the rest of his days, he attended Cleveland area baseball functions and roasts, the baseball writers’ dinner, and a few old-timers games. One of the first old-timers affairs drew 7,000 fans to a July 3, 1938, exhibition game at League Park, which pitted the ballplayers from the 1920 World Champion Indians against the 1908 Naps. Tris Speaker led the 1920 team and, because Nap Lajoie was ill, the 1908 team was led by George Stovall. As one might imagine, the 1920 team was younger and fitter. Speaker was able to start the entire lineup that had played in the Series. Cy Young threw one inning for the ’08 team and held the younger men scoreless. Elmer Smith even hit a home run in the seventh inning, though the bases were not full. Wamby did not pull off a triple play. [Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1938]

In 1939, an attempt was made to launch a new venture, the name of which was self-explanatory: Tris Speaker was the president of the eight-team National Professional Indoor Baseball League. It was launched on November 14 with Eastern Division teams in New York, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Boston, and Western Division teams in Cleveland, Chicago, Cincinnati, and St. Louis. Bill Wambsganss was the manager of the Cleveland club. The league’s other managers were Gabby Street, Brick Owens, Moose McCormick, Harry Davis, Joe Dugan, Freddy Maguire, and the same Otto Miller whom Wamby had retired as the third man out in the 1920 triple play. The game was similar to softball, with 60-foot distances between the bases, and a 12-inch-circumference ball thrown underhand from 40 feet away. Though the league insisted it was baseball and not softball, a reporter noticed the words “soft ball” imprinted on the ball. The league started play later in November, but didn’t last long.

About 2,000 turned out for Opening Day in New York on November 19, and saw Brooklyn and New York split a doubleheader. The head of the Amateur Softball Association warned ASA players that they would lose their amateur status if they played in the pro league. By December 2, Wambsganss said, “It looks as if the league might suspend.” Several games were played, though the Chicago team never came together. On December 22 Speaker announced in Cleveland that the league would discontinue, citing the lack of sufficient availability at indoor venues.

Wamby’s next experience with another form of baseball was his involvement with the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, the wartime venture that was founded in 1943 and ran until 1954. Wamby managed the 1945 Fort Wayne Daisies and the 1948 Muskegon Lassies. With a record of 62-47, the Daisies came in second to the Rockford Peaches (67-43) in the six-team league. There were 10 teams in the league by 1948, broken into two divisions. The Muskegon Lassies (66-57) came in second in the Eastern Division, well behind the 77-47 Grand Rapids Chicks.

The 1948 Indians brought the World Series back to Cleveland, and Wambsganss took in–as a spectator this time–his first Series since 1920. Speaker, Steve O’Neill, Elmer Smith, George Uhle, and Jack Graney also attended.

Wamby left the Muskegon Lassies after the 1948 season to go into business in Cleveland. Beginning in late 1948, he worked for years in the sales department of Tru-Fit Screw Products Corporation. It may not have been coincidence that 1949 was the year that Bill Jr. reached the highest level in Cleveland sandlot baseball and Bill Sr. left managing of girls baseball to become involved in city sandlot ball. Bill Jr. played some second base growing up, and in April 1953 tried out for the Western Michigan College team.

Bill Sr. kept involved the game, managing some industrial teams in the city (including the Tru-Fit team, Lyon Tailors, and Fisher Foods) and supervising some youth baseball as well. An April 15, 1953, article in The Sporting News talked of the time he’d been overseeing players 14 and under in Class F of Cleveland sandlot baseball and encouraged future major league pitcher Al Aber.

Wambsganss made the news after nine-year-old Mickey Tabor of Paducah, Kentucky, pulled off an unassisted triple play on June 18, 1960. Tabor underwent open-heart surgery for a birth defect at St. Vincent Charity Hospital in Cleveland in mid-July. He had hit a grand slam the day before admission for the scheduled surgery, and Wambsganss came by his hospital room with a scrapbook of clippings of his 1920 World Series triple play. Mickey had runners on second and third, caught a liner behind second base, stepped on the bag, and saw the runner from third was still moving toward home plate so he ran over and stepped on the third-base bag.

In retirement, Wambsganss was often asked about his triple play and received at least a few letters and requests for autographs every week. He knew he’d been fortunate. “There were a lot of pretty good ballplayers in my time who have been forgotten,” he told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor, “but they remember me because of that one play. It’s identified me through the years. You’ve been around baseball long enough to know that it’s one of those once-in-a-lifetime things because everything has to fall in place at the right moment. … There are always a lot of opportunities. There are men on first and second, or three on, with nobody out, in almost every game. Why more aren’t made, I don’t know.” [Christian Science Monitor, February 17, 1964]

Asked about other moments in baseball, he recalled Joe Cronin with some pride. “I was at Kansas City in either ’28 or ’29 when Joe Cronin arrived and I must have helped him a little bit because he’s been a long-time friend. He used to stand behind me and watch my footwork, my balance, and my throws. He was a boy who really wanted to learn. It’s been thrilling to me to watch Joe progress in the game through the years. He’s a fine gentleman.” [Ibid.]

Wamby underwent a double hernia operation in the spring of 1965 and retired from Tru-Fit. McGuire and Gormley report that he had battled depression in the years after baseball and was briefly–and successfully–treated in a hospital. [McGuire & Gormley, op. cit., p. 192]

He lost Effie in 1977 just before their sixtieth wedding anniversary, but he enjoyed his three children and 10 grandchildren. He was feted by the Indians over the years, and in February 1979 was presented with the club’s Nostalgia Trophy at an event attended by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, heavyweight boxing champion Larry Holmes, and other sports celebrities. He was back in the news briefly in 1980 when he broke his ankle while out flying a kite–at age 86. He was active in senior citizen activities right up until November 1985, when he was hospitalized for heart failure, of which he died on December 8. The record books show him as playing in 1,491 major-league games with a .259 batting average. He had a .958 fielding percentage, except in World Series play, when it was 1.000.

Sources

Sources are noted within the text. Thanks to Norman Macht and Tom Ruane for confirming the details of the Dud Branom trade.

Full Name

William Adolph Wambsganss

Born

March 19, 1894 at Cleveland, OH (US)

Died

December 8, 1985 at Lakewood, OH (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.