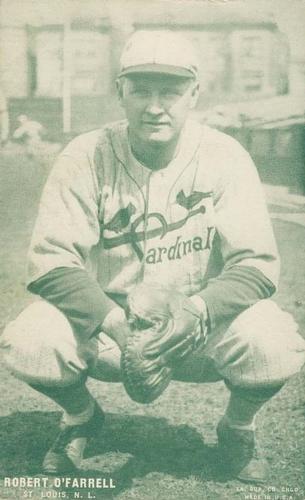

Bob O’Farrell

It is known as “creative license” and in Hollywood it often becomes urban legend and, unfortunately, even fact to many. In the movie, The Winning Team, a biography of pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, such a measure was employed. The film, starring Ronald Reagan as Alexander and Doris Day as his wife, Aimee, was released in 1952.

It is known as “creative license” and in Hollywood it often becomes urban legend and, unfortunately, even fact to many. In the movie, The Winning Team, a biography of pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, such a measure was employed. The film, starring Ronald Reagan as Alexander and Doris Day as his wife, Aimee, was released in 1952.

The climax of the movie is Game Seven of the 1926 World Series between the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees. The Yankees had just loaded the bases against Cardinals starter Jesse Haines, and Alexander is summoned from the bullpen by St. Louis manager (and second baseman) Rogers Hornsby. “Alex the Great,” as he is referred to, strikes out Tony Lazzeri to preserve the first World Championship in St. Louis Cardinals history.

Not so fast. These events actually occurred in the seventh inning, not the ninth as the movie’s executives would have you believe. No, the real story is that the ending happened in a much different way. And although Alexander was the hero of the day, it was Bob O’Farrell who put the finishing touch on the Cardinals’ victory.

O’Farrell, the backstop of the Cardinals, relayed the circumstances to Lawrence Ritter in The Glory of Their Times. “Most people seem to remember that as happening in the ninth inning, and ending the ballgame,” said O’Farrell. “It didn’t. It was only the seventh inning and we had two innings still to go. In the eighth, Alex set down the Yankees in order, and the first two men in the ninth. But then, with two out in the bottom of the ninth, he walked Babe Ruth. Bob Meusel was next up, but on the first pitch to him the Babe took off for second. Alex pitched, and I fired the ball to Hornsby and caught Babe stealing, and that was the last play of the game and the Series.

“You know, I wondered why Ruth tried to steal second then. A year or two later I went on a barnstorming trip with the Babe and I asked him. Ruth said he thought Alex had forgotten he was there. Also that the way Alex was pitching they’d never get two hits in a row off him, so he better get in position to score if they got one. Well, maybe that was good thinking and maybe not. In any case, I had him out a mile at second.”1

Robert Arthur O’Farrell was born on October 19, 1896, in Waukegan, Illinois, the second son (with his brother Harold) born to Sars and Amy O’Farrell. Sars O’Farrell worked as an electrician, but later was the fire chief of Waukegan.

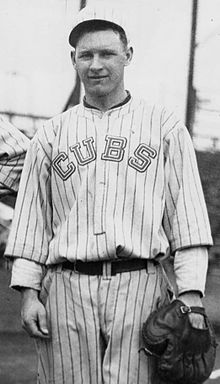

O’Farrell’s parents encouraged their son to participate in sports at an early age. The elder O’Farrell also brought up his youngest son to be a White Sox fan. He was a member of the baseball team at Waukegan High School, and joined a Waukegan semipro team. Nobody wanted to be the catcher, so O’Farrell took the job because it was the sure way to stay on the field. He caught a break when the Waukegan team was hosting an exhibition game against the Chicago Cubs in 1915. O’Farrell caught the eye of Roger Bresnahan, the Cubs player-manager. Bresnahan was in the last year of a Hall of Fame career, and he knew talent behind the plate when he saw it. O’Farrell joined the Cubs that year, making his major league debut on September 5.

O’Farrell appeared in only a couple of games. The following year he served as a bullpen catcher before being sent down to Peoria of the Three-I (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa) League to gain more experience. He spent all of the 1917 season there as well. He batted an even .300 for the Distillers in 1917.

O’Farrell rejoined the Cubs and he was in the big leagues to stay. In 1918 he served as the backup catcher to Bill Killefer. But the season was shortened as a result of World War I and it concluded on Labor Day. The edict that was given to the players was to “work or fight,” It was a good time to be a member of the Cubs as they captured the National League pennant. But Chicago lost to the Boston Red Sox in six games, as Babe Ruth and Carl Mays each went 2-0.

Killefer was starting catcher in 1919 with O’Farrell as his backup. But the following year, Killefer suffered a gash to his forehead and a broken right index finger that sidelined him for a good portion of the season. O’Farrell stepped into the starting role, starting 75 games.

Johnny Evers was relieved as manager of the Cubs in 1921 and Killefer was named as his replacement. Despite the change in managers, the Cubs finished in seventh place, 30 games behind the league champion Giants. O’Farrell was again given the bulk of the catching duties. O’Farrell was described as a laid back receiver. He seldom tussled with umpires and he went about his job absent of much fanfare. He was known for his defense, specifically his throwing arm, ability to block pitches in the dirt, and his handling of a pitching staff.

In 1922, O’Farrell led the league in games started (119), putouts (446), assists (143), and double plays (22). He threw out 83 of 126 (66%) would-be base stealers. He also batted a career-high .324. In 1923, O’Farrell set career highs in home runs (12) and RBIs (84) while batting .319.

In a game on July 22, 1924, an injury to O’Farrell knocked him out of the Cubs lineup for three weeks. Essentially, it cost him his starting job. In the first inning of the first game of a doubleheader, a foul tip off the bat of Stuffy McInnis struck O’Farrell’s catcher’s mask. The impact caused the steel support rods to jam right into O’Farrell’s forehead far enough that he suffered a concussion. He was rushed to the hospital where he would remain for two to three weeks.

“It was my own fault,” O’Farrell said to Ritter. “It was an old mask and I knew I shouldn’t have worn it. You know, a lot of times a catcher’s mask gets so much banging around it gets dented here and there. If you try to bend it back the way it’s supposed to be, it weakens it. Well, I got on an old mask that day and asked the clubhouse boy to go get me my regular one. Before he could get back with it, the ball had spun off the bat, smashed through the mask, and knocked me unconscious.”2

O’Farrell’s misfortune opened the door for Gabby Hartnett. He had joined the club in 1922, as Killefer retired as a player after the 1921 season to tend to his managerial responsibilities full time. Hartnett stepped right into the starting role. He was more of a fiery, no-nonsense catcher than O’Farrell. He took to his new role, parlaying it into a career that would eventually end with enshrinement in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The emergence of Hartnett made O’Farrell expendable. On May 23, 1925, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for catcher Mike Gonzalez and utility player Howard Freigau. O’Farrell went from bench warmer to starting catcher with the Cards. Hornsby took the managerial reins from Branch Rickey at the end of May. O’Farrell provided a steadying influence behind the plate. St. Louis moved from sixth place in 1924 to fourth place in 1925.

Maybe the biggest difference between the Cards of 1925 and 1926 was the pitching. Flint Rhem posted an 8-13 record in 1925 and the next year led the league with a 20-8 record. Jesse Haines won 13 games both seasons. But in 1925 he had 14 losses and in 1926 he only had four defeats. And he lowered his ERA by one run.

As it turned out, the Cardinals may have made their biggest move when they signed Alexander on June 22 after he was waived by the Cubs. He and O’Farrell had been teammates for years with the Cubs, so Alexander knew exactly what he was getting in a catcher. For instance, O’Farrell did not go through the trouble of flashing pitch signs to Alexander, rather he just faked them. “He don’t pay no attention to me and I don’t pay no attention to him. I just pitch whatever I happen to want to pitch and I know Bob will get ‘em all.”3

After splitting a doubleheader on September 18 with Philadelphia, the Cardinals were one game ahead of Cincinnati. St. Louis finished the season with a 2-4 record. But the Reds could not close the gap, going 2-4-1 in the same period, being swept by the seventh-place Boston Braves.

O’Farrell was being considered for Most Valuable Player honors, and Hornsby agreed. “Bob ought to win the most valuable player prize,” said Hornsby. “He’s done more for us than any other player and the whole team is pulling for him to win. You know he’s caught more games than any other catcher in either league. All the pitchers want him there. There’s no better catcher in baseball.”4

O’Farrell did win the top prize, although his statistics were not overwhelming. He batted .293 with seven home runs and 68 RBIs. He led the league in games started (142) and putouts (466). He fielded his position at a .983 clip.

Even though the Cardinals won their first world championship in 1926, there was friction between Hornsby and club owner Sam Breadon. So it might not have been a big surprise when Hornsby was traded to the New York Giants for Frankie Frisch and pitcher Jimmy Ring on December 20. O’Farrell was named player-manager for the 1927 season. “I am greatly pleased over the signing of O’Farrell as manager,” said Breadon. “My one ambition was to get one of the world champions as manager and I do not think I could have picked a better man than O’Farrell.”5 To give O’Farrell a hand with his new post, Bill McKechnie was hired as a coach. McKechnie had piloted Pittsburgh for five seasons (1922-1926).

Because O’Farrell was battling injures to his shoulder and right thumb for much of the season, he split the catching duties with Frank Snyder and Johnny Schulte. The Cardinals finished in second place, 1 ½ games behind Pittsburgh. Ironically, they had a better record in 1927 (92-61) then they had in the pennant-winning year of 1926 (89-65-2). The tale of the tape was in their head-to-head matchups with Pittsburgh. The Cardinals went 8-14 against the Pirates during the regular season. O’Farrell was relieved as manager and replaced with McKechnie. “O’Farrell was successful as a manager,” said Breadon, “but I have considered the problem carefully and I think that the worries of managing the club handicapped him. In 1926, he was the league’s most valuable player and the best catcher in baseball. In 1927, perhaps because of the managerial responsibilities, he was injured several times and able to catch only a few games. Had he escaped injuries I believe we would have won the pennant. To spoil a great catcher like O’Farrell is an expensive way of obtaining a manager and for that reason, after a conference with Bob, I decided to make a change.”6

O’Farrell married Arolene Edwards of Churchville, New York, on February 15, 1928. They had one son, Robert.

On May 10, 1928, O’Farrell was traded to the Giants for outfielder George Harper. “I consider this a good trade for the Giants,” said New York manager John McGraw. “O’Farrell is one of the ranking catchers of the majors, and we have protected ourselves by stipulating that he must come to us in good condition to catch good ball or the trade is automatically cancelled. We have no doubt that O’Farrell will help us.

On May 10, 1928, O’Farrell was traded to the Giants for outfielder George Harper. “I consider this a good trade for the Giants,” said New York manager John McGraw. “O’Farrell is one of the ranking catchers of the majors, and we have protected ourselves by stipulating that he must come to us in good condition to catch good ball or the trade is automatically cancelled. We have no doubt that O’Farrell will help us.

“(Shanty) Hogan’s status is in no wise affected by this trade. Hogan has worked hard and hustled. He has hit in runs in the pinches and done everything we asked him to do.”7

And that’s exactly how it played out. O’Farrell backed up Hogan at the catcher position from 1928 to 1932. He batted .266 in 395 games. Although the Giants were near the top of the NL standings and in contention for most of O’Farrell’s time, he did not enjoy playing for McGraw.

“Now, McGraw, he was tough as a manager,” said O’Farrell. “Very hard to play for. I played for him from 1928 to 1932, when he retired, and I didn’t like it. You couldn’t seem to do anything right for him, ever. If something went wrong, it was always your fault, not his. Maybe it was because he was getting old and was a sick man, but he was never any fun to play for. He was always so grouchy.”8

The Giants packaged O’Farrell in a six-player swap back to the Cardinals on October 10, 1932. After spending the year backing up Jimmie Wilson, O’Farrell was on the move again. He was sent to Cincinnati with pitcher Syl Johnson in return for pitcher Glenn Spencer on January 11, 1934.

As it turned out, the appointment was an abbreviated one. On July 26, 1934, the Reds were in last place with a 30-60-1 record. O’Farrell was canned. He was picked up by the Cubs on August 6; the Cubs trailed the Giants by only three games. But neither the Giants nor the Cubs took the pennant, as the Cards won it in 1934.

O’Farrell finished his major league career in St. Louis, appearing in only 14 games for the Cards in 1935. He was released on December 9. O’Farrell retired after a stint with the Rochester Red Wings in 1936 and 1937. In 1,492 games over 21 years, O’Farrell had a lifetime batting average of .273. He clubbed 51 home runs and drove in 549 runs. His lifetime fielding percentage at catcher was .976. He threw out 48% of would-be base stealers.

In retirement, O’Farrell operated O’Farrell Recreation in Waukegan. The recreation hall was a bowling alley and a billiards room. O’Farrell, who enjoyed a round of golf whenever he got the opportunity, was a good bowler in his own right. He carried a 200+ average for many years while a member of the American Bowling Congress.

Robert O’Farrell passed away on February 20, 1988, at St. Theresa Medical Center in Waukegan.

Last revised: September 29, 2023 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Notes

1 Lawrence Ritter, The Glory of Their Times, New York: Macmillan Company: 1966, 237

2 Ritter, 235

3 Charles C. Alexander, Rogers Hornsby, New York: Henry Holt and Company: 1995, 119,

4 J. Roy Stockton, “O’Farrell Worked So Quietly That He Became the Big Noise Among Catchers”, St, Louis Post-Dispatch, August 27, 1926: 32,

5 J. Roy Stockton, “Bob O’Farrell Takes Up Duties As Cardinals’ Manager Today”, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 28, 1926: 20,

6 J. Roy Stockton, “McKechnie Made 1928 Manager Of Cardinal Team”, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 7, 1927, L 1,

7 “Giants Acquire O’Farrell In Trade”, New York Times, May 11, 1928, 28,

8 Ritter, 239-240,

Full Name

Robert Arthur O'Farrell

Born

October 19, 1896 at Waukegan, IL (USA)

Died

February 20, 1988 at Waukegan, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.