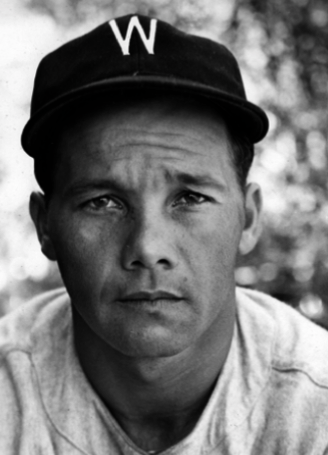

Bobby Estalella

Estalella was a pudgy, happy-go-lucky sort of a guy who struck people the right way.” — Ossie Bluege1

The 12th player among those in Dave Frishberg’s “Van Lingle Mungo” lyrics lineup is Roberto Estalella, and he is united by rhyme with Danny Gardella, the song’s sixth man.2 There may not have been anything intentional about it, but nonetheless, they encountered each other elsewhere in the arts as well as on the ballfield. Baseball fans are now more familiar with his namesake grandson Bobby Estalella, who debuted in major-league baseball in 1996, playing for the Phillies, Giants, Yankees, Rockies, Diamondbacks, and Blue Jays. Less is remembered about the original Roberto Estalella, who graced the infield and outer garden of the Washington Senators, the St. Louis Browns, and the Philadelphia Athletics between 1935 and 1949, with a brief hiatus spent in the Mexican League. But like many lesser-known players, he is the star of a monumental saga, and like many other players who have left indelible impressions and memories, he accumulated nicknames, attesting to his popularity with fans and reporters: “El Tarzán,” “Cuba’s Gift to the Washington Senators,” “The Hotcha Kid,” “Esty,” and “Cheese and Crackers.” Sportswriters routinely called him “Bob” and “Bobby.” Roberto Estalella’s story begins in 1933 with the Washington Senators, Clark Griffith, and baseball scout Joe Cambria.

The 12th player among those in Dave Frishberg’s “Van Lingle Mungo” lyrics lineup is Roberto Estalella, and he is united by rhyme with Danny Gardella, the song’s sixth man.2 There may not have been anything intentional about it, but nonetheless, they encountered each other elsewhere in the arts as well as on the ballfield. Baseball fans are now more familiar with his namesake grandson Bobby Estalella, who debuted in major-league baseball in 1996, playing for the Phillies, Giants, Yankees, Rockies, Diamondbacks, and Blue Jays. Less is remembered about the original Roberto Estalella, who graced the infield and outer garden of the Washington Senators, the St. Louis Browns, and the Philadelphia Athletics between 1935 and 1949, with a brief hiatus spent in the Mexican League. But like many lesser-known players, he is the star of a monumental saga, and like many other players who have left indelible impressions and memories, he accumulated nicknames, attesting to his popularity with fans and reporters: “El Tarzán,” “Cuba’s Gift to the Washington Senators,” “The Hotcha Kid,” “Esty,” and “Cheese and Crackers.” Sportswriters routinely called him “Bob” and “Bobby.” Roberto Estalella’s story begins in 1933 with the Washington Senators, Clark Griffith, and baseball scout Joe Cambria.

Estalella explained that he learned how to bat and take a terrific cut at a ball by swinging a bat in the same arc as cutting sugar cane. He was born on April 25, 1911, in Cardenas, Cuba, where he played baseball on a company team comprising workers from the sugar fields, deep within a culture rich with baseball talent. Cuba had been known for decades as fertile territory for American baseball organizations seeking raw young players, but there were a few bothersome problems. There was the language barrier. Cuban players rarely knew even a little English and there was no organized effort to teach them once they arrived here. American scouts, Joe Cambria included, were not inclined to learn Spanish. And then there was the pigmentation issue.

“Everybody having a known trace of Negro blood in his veins – no matter how far back it was acquired – is classified as a Negro. No amount of white ancestry, except one hundred per cent, will permit entrance to the white race.” — Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma, Vol. I, 1944

When Roberto Estalella debuted with the Washington Senators in 1935, his introduction included the remark that he was “born of Spanish parents in Havana,” and, adding a note of poverty-stricken innocence, that “he never wore a pair of shoes until he was 11 years old.”3 His arrival in the United States inspired a rags-to-mythical-riches tale guaranteed to delight fans.

He had played baseball in Cuba with the amateur and semipro teams Club Deportivo Cardenas and Central Hershey.4 Cambria, known as the “laundry man” for his side job of providing laundry services around Baltimore, an enterprise that employed some of his acquisitions in the offseason, heard about Estalella in 1933 from Albany outfielder Ismael Morales, Estalella’s teammate in Cuba’s winter league.5 “He hit good, he field all right, he good arm and he pretty fast. You better take a look at him queek before some other club pick heem up,” Morales advised Cambria.6 Estalella hit a “crucial late-inning home run” which won the season’s final game for Havana’s Leones in the 1932-33 winter season, bringing about a tie with the rival Alacranes.7 Estalella had hit .351 in the 1931-32 season and .317 in 1932-33.8 Almost every year from 1936-37 through 1953, he played winter ball in Cuba. Using Morales as the go-between, Cambria offered Estalella $150 a month, which was attractive money for an apprentice machinist earning $1.20 a day at a Cuban sugar refinery. Transportation and a meal allowance were sent to Estalella’s home in Cardenas.

“I [made] myself plenty [of] trouble,” Estalella said when he recalled that July day in 1934 when he arrived by boat from Havana at Key West with a ticket pinned to the lapel of his coat with the instruction: “Albany, New York. Please deliver to the baseball park.”9 The customs officer, realizing the young man could not speak any English at all, handed him a slip of paper and told him to keep it in his hand at all costs. At Jacksonville, Florida, he encountered difficulty finding something to eat. The food seemed familiar to him but he didn’t know how to ask for anything. He pointed at a bottle of milk and then noticed a man enjoying a slice of pie, so he thought that might do for him, too. Unfortunately it was peach pie. “I no like peaches, he recounted later. “But I was so hungry I eat all the pie – one hand, too, because I hold slip in other hand.”10

The train brought Estalella as far as Washington D.C., and not knowing what else to do in this bewildering situation in which he found himself, he espied the sign “Information,” and, figuring it was close enough to “Información,” he took a chance and indicated to the woman at the booth that he needed help. With rudimentary hand signals and drawings she made him understand that the bus he was to board would leave at 10:45. A porter was summoned to escort him to the bus. All that kindness of strangers succeeded in getting him to Albany, where he arrived 72 hours later, not having slept the entire time. Once there, Estalella showed that critical slip of paper in his hand to a policeman who put him in a taxi and sent him to the ballpark. Cambria had expected him to arrive in May, but instead Estalella appeared unexpectedly in midseason and consequently did not appear in a game until September 5, 1934. His story continued to be nothing less than classic baseball history.

Local cuisine continued to be a problem. The manager of the Albany club took Estalella out to breakfast and ordered up a plate of ham and eggs. Estalella, considering the dish acceptable, remembered the three words and over the next month ate nothing else for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. This illustrated how Roberto Estalella acquired much of his English – picking up words casually and inserting them into his mental dictionary. His fractured English was a source of amusement among sportswriters, managers, and fellow players, and he was accused of hiding behind a feigned ignorance of the English language. And yet, when it came to needing someone to bridge the language gap, Estalella was called upon to intervene. Clark Griffith, president of the Washington Senators, the team that Estalella joined in 1935, said he regretted releasing Moe Berg in 1934, for in that day and age, learning even a little Spanish was never considered practical by managers or players except, perhaps, for Moe Berg.

“He’s just the man to talk to some of these foreigners,”11 Griffith lamented, pointing out that he had Roberto Ortiz, a Cuban pitcher who spoke no English; pitcher Rene Monteagudo, who spoke very little English; and Venezuelan Alejandro Carrasquel, whose name was so confounding to Griffith that he renamed him Al Alexander. And there was Joe Krakauskas, a Canadian of Lithuanian descent who did speak English – with an accent – but when overly excited, Griffith couldn’t understand at all what language he spoke. “The way things are going now, we sound like a row in the League of Nations.”12 With no formal English-language classes, players had to pick up whatever they could hear. Joe Cambria did not think players should learn English and believed the Latin recruits would get along better if they were not able to express any opinions or complaints or let on that they knew what was going on when the manager bawled them out.13

The story of Estalella’s arrival in America served to entertain readers, but the tale also portrayed a stereotypical ignorant immigrant, while overlooking the fact that it took Estalella a great deal of wit and creativity to travel alone from Cuba to Key West and all the way to New York and actually arrive at the intended destination.

Roberto Estalella’s professional career began in earnest in 1934 in Albany. Cambria, actually owned the Albany Senators of the International League, the minor-league team that served as the portal for raw talent intended for the Washington Senators. He moved on through the minor-league ranks to the Harrisburg team – also owned by Cambria – of the New York-Penn League in 1935, hitting .316 with a league-leading 18 home runs.14 August 9, 1935, was “Bobby Estalella Night” at Harrisburg’s Island Park, a tribute to how far he had come in winning the esteem of fans. By this time Estalella had been dubbed “Tarzan” for the yell he belted out every time he stepped up to the plate, described as akin to that heard in the popular Tarzan movies starring Johnny Weissmuller.

Reports conflicted about how much Estalella was improving. Local baseball fans supported him while Harrisburg Telegraph columnist Nobe Frank remained a skeptic: “Call it a hunch or whatever you will, I cannot see Bobby Estalella staying up there in the big leagues. Of course, the type of team that the Washington Senators have been sporting the past few years cannot exactly be classed as big league.”15

The subsequent backlash from fans was unrelenting, but Frank was still not convinced of Estalella’s impending greatness, and wanted him banished from Harrisburg. As he saw it: “Estalella has been spoiled by the fans’ hero worshipping adulation. He has come to think that everything he does is O.K., whether he swings three times and misses or loses one over the fence. He has that inherent flair for color and the bizarre. … He struts to that plate like Casey at the bat, and as many times does the same as Casey in the clutch, but he has the mistaken impression that as long as he swings heftily, though breezily, and gives the fans a treat, everything is O.K. for Bobby.”16

Mr Frank: Personally I think your article in the paper Monday night was terrible, and that you are more detrimental than anything we know by attempting to write an article of that sort. The only time the games have any pep whatsoever is when Bob is playing. — Signed: Two Lady fans that have never missed a game.17

On September 7, one month after Frank’s tirade, Estalella made his major-league debut at third base with the Washington Senators. He appeared in 15 games near the end of the 1935 season, hit .314 with two home runs, had a .485 on-base percentage, and immediately became the idol of the Washington fans. Years later, in 1949, Shirley Povich wrote that fans would call the ballpark to see if he was in the lineup before deciding whether they would come to the game.

Estalella later recalled an incident where he was suddenly introduced to Goose Goslin. “I play third base while I was with Washington, and one afternoon de player named Goosie Gooslin slid into the base and I tagged him out. He got mad and kicked at me and I kicked back. He get up and poosh me and I pooshum back. I couldn’t speak over 20 words in English and when the umpire came up and asked what was the matter, I couldn’t tell him. I got mad and just said quack, quack, quack.”18

Estalella returned to the Senators in 1936, making only 13 plate appearances. Manager Bucky Harris noticed that he was using a cheap, inferior glove, and once provided with a professional mitt, his fielding dramatically improved. Also improved, as Harris observed, was Estalella’s English-language proficiency. Yet, he still had to win over the Senators staff even when fans and other observers applauded his ability and charisma. While at batting practice at Fenway Park in April, 1936, Senators southpaw Earl Whitehill was tossing a few warm-up pitches. Not until Estalella stepped up to bat did he actually ramp it up and let loose with his best stuff. He threw all his best fastballs and curves at Bobby, seemingly determined to make him look bad, but Estalella dug in and, much to the amusement of the spectators, he hit three consecutive pitches over the left-field wall.

Estalella’s work at third base during that game at Fenway Park caught the attention of reporters and fans, but apparently not that of his manager or the team owner. The team continued to harbor doubts about his defense, so he was returned to Joe Cambria in Albany on condition that he get more playing time and a trial in the outfield. While there, he hit .331 with 14 home runs. He started the 1937 season with Chattanooga and maintained a .299 average before the Senators shifted him to the Charlotte club of the Piedmont League.

Estalella’s fielding was apparently a source of some amusement in D.C. at the time. Peter Bjarkman writes, “Washington fans of the late thirties had so much fun watching the gritty Estalella knock down enemy grounders with every part of his anatomy save his glove hand that they often phoned the park in advance to find out if the handsome swarthy Cuban was in the lineup before making the trek out to the usually sparsely populated Griffith Stadium grandstands.”19

From 1936 through 1938, Roberto Estalella wandered around minor-league baseball. He continued to be a fan favorite and he also built a reputation among baseball players he encountered along the way. His statistics continued to reflect a player with good potential, but always something would interfere with his return to the Senators. He was called a “notoriously slow starter at bat … a weak sister with the stick during the first month of the season.”20

“Estalella can powder a ball and can really toss an agate around but he just doesn’t seem to be major league timber,” wrote Al Clark, sports editor of the Harrisburg Telegraph, in April 1938. What one needed to fulfill that requirement is lost in the fog of Estalella’s minor-league statistics. What was it that he lacked in the eyes of coaches, managers, and club owners? Bucky Harris considered him a very bad fielder, and his arm was suspect, but he could hit,. Estalella would have made it on the roster if the decision had been left in the hands of the fans, who adored him. At the end of the 1938 season in Charlotte, his batting average was .378, better than his 1937 average of .349, and he had won the batting crown for the Hornets for the second year in a row, despite being out for part of the season with a broken jaw caused by a fungo bat thrown by a teammate.

Bats were not the only object Estalella had to beware of while playing with minor-league teams in the South. He was known to rocket line drives that traveled back toward the pitcher, some of whom refused to throw batting practice to him. One incident so angered a pitcher that he grabbed a ball and threw at Estalella’s head, dropping him to the ground. Such incidents became routine and pitchers in the Piedmont League had a field day knocking Bobby down for nearly two years and peppering him with epithets disparaging his ethnic origin. Despite the controversies, he was named by The Sporting News as the Most Valuable Player in the Piedmont League in 1938 by one point over Phil Rizzuto of the Norfolk Tars. “He’s learned a lot since I saw him last,” said Harris. “He isn’t a bad fielder at all and he’s fairly fast. Best of all, he’s got a great arm and plenty of power at bat.”21

Two impressive years in minor-league baseball earned Estalella a return trip to Washington, where other issues came up. Calvin Griffith had to keep him on the roster in 1939 or lose him because he was out of options. In order to make room for Estalella on the roster, Griffith traded Zeke Bonura to the Giants and sold Al Simmons to the Boston Bees, a move that shocked many. Griffith said he did so because Simmons had “used profane language in front of ladies at the park last year. I won’t stand for a player of mine cursing fans, and when Simmons did it, he washed himself up as far as my club was concerned.”22 Griffith also denied that he made the Bonura-Simmons moves because he could drop $25,000 in salaries to make room for the cheaper Estalella, who was paid $2,750 in 1939. Griffith was also accused of using the Cuban players on his roster for publicity purposes to hide a bad ballclub behind “circusy press notices.”23

The 1939 season appeared to be Estalella’s best chance of returning to the Senators roster, and the way looked clear for him to inherit the left-field position. He finished the season with the Senators with a “disappointing” .275 average in 82 games. Doubt and skepticism remained. “Estalella cowhides minor league pitching, but they say he doesn’t like the high hard one inside.”24 Bucky Harris still expressed concerns, for in early in spring training, he noticed that the star hitter of the Piedmont League seemed to be having difficulty hitting curveballs. Despite making progress and getting extra batting practice from the Senators pitching staff, he was sent back down to the minors, to Minneapolis in the American Association, because, Griffith explained, “the American Association will give Estalella the kind of minor league experience he needs. It’s lots faster than the Piedmont.”25

At Minneapolis in 1940, Estalella maintained a .341average and hit 32 home runs. In 1941 the St. Louis Browns, his next major-league experience, gave him the chance to compete for the right-field job. Tom Sheehan, who had managed the Minneapolis team where Estalella had played the previous year, was convinced the “Cuban thunderbolt” had solved his problems with curveballs.26 He received a raise to $3,500, but appeared in only 46 games, mainly as a pinch-hitter. His baseball career again stalled, as he was sent back down to the minors, this time to Toledo.

World history changed the course of Estalella’s career when the United States entered World War II. Once again Clark Griffith acquired him from the Browns, for $7,500 – and paid him a $3,500 salary – and was interested in adding him to the Senators roster, but it was not merely because of Estalella’s continued minor-league accomplishments that the Old Fox wanted him back. By March 1942, 13 Washington players had been drafted or had enlisted in the armed forces; the Cuban players were granted six-month visas and called “entertainers,” which exempted them from the draft. Estalella was also outhitting any other prospect available at the time, and Bucky Harris acknowledged that the time spent playing winter baseball in Havana had given him a big advantage.

The fans still loved Estalella, and his English language skills still fascinated: “Estalella, a squatty number built closer to the ground than a flat tire, wields one of the few big bats on the weak-hitting Washington squad. Bobby is the club’s ‘chatter guy.’ His scrambled Cuban-English has the crowds in the aisles. Here are a few samples of Bobby’s repertoire. ‘Hong rong’ is home run. ‘Tubeis’ means a double. ‘Mata el arbitro’ translates as kill the umpire and ‘keche’ is the Cuban for catcher.”27 Not everyone was amused. Harris complained that Joe Cambria was inflicting him with the painful duty of looking after a bunch of temperamental players. “Bah! Cuban ballplayers. Haven’t I enough troubles without Cambria bringing me some more of those rhumba dancers to look over.”28

The 1942 season turned out to be Estalella’s most productive year to that point in the majors, as he hit .277 with an on-base percentage of .400 in133 games, while playing mostly third base and left field. His baseball career took a major turn during the 1943 season, when he was traded to the Philadelphia Athletics, who sent Bob Johnson to the Senators after he and Connie Mack couldn’t agree on the bonus Johnson said he had coming to him. Although Mack lost an All-Star player, he was relieved of the $10,000 salary he was paying Johnson, and acquired Estalella, whom he paid $4,000.

Johnson’s and Estalella’s stats were not very different over the remainder of their careers, but Mack would eventually lament that after all was said and done it was not a good deal, and said he truly missed Johnson after he was gone. Johnson, with the Senators that year, appeared in 117 games. His batting average was .265, his OBP was .362, and he hit seven home runs. In 1943 Estalella also played in 117 games, batted.259 .352 OBP), and hit 11 home runs. He also brought his flamboyant personality to the ballpark and continued his knack for putting fans in the seats. He finished the 1943 season as the leading hitter on the Athletics. What was not to like? Estalella did spend a brief exile in the minors again. Despite the .259 average, Mack sent him to Indianapolis for Jo-Jo Moore, the veteran Giant outfielder, but Moore was inducted into the Army and Roberto was back up again.

It was not just language that set Roberto Estalella apart from his teammates. He was a different sort of player than what Americans were used to. Exuberant at the plate, irrepressible on the field, and relentlessly noisy in the clubhouse, he arrived in the US bringing with him a style of baseball that was lost in translation by the American managers, magnates, and teammates.

Roberto Estalella lamented that in the eight years that he been playing baseball, he had always been with clubs deep in the second division. When he joined the Philadelphia Athletics, Connie Mack heard about his lament and chuckled: “Don’t worry sonny,” he told him. “We’ll probably make you feel right at home. [You’ve] come to the right place to keep that record intact.”29

Estalella arrived at spring training in Frederick, Maryland, in 1944, just back from another winter playing ball in Havana, waving the new bat he predicted was going to “show zem somesing weeth thees thees year.”30 The majagua wood bat, from the tropical pariti tiliaceum tree, would surely improve his game and bring him luck. “Nine years and never weeth a contender,” Roberto said, his brown eyes flashing “Always eet was the second deevision – and sometimes even the third deevision. But thees year he’s deferent. I theenk we have thee chance for thee pennant. Meester Mack he says so and I think heem right.”31

Shortly after the 1944 season opened, the Detroit Tigers came to Shibe Park. The players of the two teams exploded into a punchless melee around the pitcher’s mound with the requisite pushing and shoving. Estalella was in the middle of it, making himself useful by picking up cast-off baseball caps, dusting them off and handing them back to the players. “Bending down, working off my stomach,” he explained, that the extra exercise was intended to decrease the weight that was affecting his batting average. He proudly reported that he had lost 30 pounds since 1943, when he weighed 210 pounds, and his batting average had increased in 1944 by as many points as pounds he lost.

By mid-May Connie Mack admitted that Estalella was not only hot, but also the “most improved” player in the major leagues. By then he was hitting .343 and his fielding had improved significantly. “It’s fruit that did it,” said Mack. “Fruit and changing his playing position. He never played center field before. The position is made for him.”32 There was no mention whether the majagua bat was a hit, but Bobby shed another 20 pounds.

Estalella was truly hot during the 1945 season. He finished with a .299 batting average and felt the ire of the Detroit Tigers, who held him personally responsible for their unfortunate finish the previous September, accused him of having a jinx bat33 and held him responsible for misjudging a fly ball that allowed the St. Louis Browns to overtake them in the standings and win the 1944 pennant. They also condemned him for hitting a line drive that fractured the leg of Tigers pitcher Al Benton, who had just returned from several years in the service. And then to add insult to injury, he also spoiled a one-hit shutout by Tigers pitcher Prince Henry Kauhane Oana by driving in the tying run with a ninth-inning double on a 3-and-2 pitch with two outs. The Athletics went on to win the game, 3-2, in 16 innings when once again Estalella doubled to bring home the winning run. The United Press reporter who wrote the story advised, “the Tigers best bet where the bothersome Cuban is concerned appears to be to buy the fellow.”34

With the end of World War II, the players who had spent years in the service contended that the GI Bill entitled them to return to the jobs they held before the war, and many of those players who were on teams during the war now found themselves back in the minors or out of a job. Players also came back from the war with a heightened awareness of dealing with the owners in regard to contract negotiations and pay. Then along came the Pasquel brothers of the Mexican League with mountains of money and promises of wealth and glory. At the start of spring training in 1946, Connie Mack, despite the rumors, still expected Estalella show up. Bobby told Mack he was examining a big wage offer from the Pasquel brothers. Mack waited. Roberto did not report.

Major League Baseball called the Mexican League the greatest threat since the Federal League.35 Estalella joined several popular players, among them Mickey Owen, Sal Maglie, Ace Adams, Max Lanier, and Danny Gardella – his eventual rhyme scheme partner in “Van Lingo Mungo.” Their adventures in Mexico were also recounted in the novel Vera Cruz Blues by Mark Winegardner.

Gordon Cobbledick of the Cleveland Plain Dealer condemned the “contract jumpers.” He wrote, “The Americans could afford to be complacent – though they were not conspicuously so – in the face of the desertion of such second-raters as Roberto Estalella, Alejandro Carrasquel and Danny Gardella, whose Latin antecedents fitted them naturally into the Mexican picture.”36 Estalella was the home-run leader of the Mexican League, slamming four homers in his first five games. His batting average in April 1946 was .471.

Eighteen players from the major leagues went to Mexico, and were punished for it with five-year suspensions handed out by a very unhappy Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler. The hardships of playing in uncomfortable circumstances – along with the Pasquel brothers’ fright-inducing business practices and their army of gun-toting bodyguards – compelled the players to come straggling back. A few were welcomed by their former teams but many, including Roberto Estalella, looked elsewhere to play ball. In 1947 he returned to winter ball for Marianao, Cuba, and was the center fielder for Pasquel’s Los Tuneros de San Luis Potosí in Mexico during the summer. “Tarzan” Estalella continued to thrill fans with his signature flamboyant, vociferous presence at the plate and in center field.

In 1948 Estalella was the left fielder for the Havana team and played great baseball, but no one in the major leagues was paying much attention. Hoping that all had been forgiven, he tested Connie Mack’s mood. Mack commented that he would expect to “dispose of” Estalella if he applied for reinstatement.37 But Mack did not dispose of him immediately. Bobby returned to the Philadelphia A’s in 1949, near the end of the season, appearing in eight games, with 20 at-bats and five hits. He was paid $2,604. In November 1949 the Browns purchased Estalella from the Athletics and sent him to their San Antonio farm club of the Texas League. After appearing in a few games with the San Antonio Missions, Estalella was sold to the Havana team of the Class B Florida International League in June 1950, after being placed on the waiver list.

Estalella’s playing days over, he returned to Washington and worked as a butcher, but he was not far from baseball. In 1955 Senators manager Chuck Dressen hired him to teach English to the next generation of Cuban players on the team – Carlos Paula, Pedro Ramos, Juan Delis, and Camilo Pascual. He appeared at old-timer’s games and events that celebrated the veteran Cuban players. When Luis Tiant, Sr. was allowed to come to the United States in 1975 to see his son pitch in the World Series, he also wanted to visit his friends and fellow players from the old Cuban teams. His list included Roberto Estalella.

Major-league teams of the 1930s, mindful of baseball’s unwritten color-line, had been walking a thin line in order not to cause controversy and also not to rile other players who might abuse a new player with darker skin. If Clark Griffith was curious, he never outwardly appeared to be concerned. A few American-born players cast the usual epithets, and other Cuban players who knew Estalella considered him to be of mixed-race heritage and had little interest or concern about his skin color. Many baseball historians contend that Estalella slipped under the discriminatory barrier that kept many great players with darker skin from reaching the major leagues before Jackie Robinson.

Author and academic Roberto Gonzalez Echeverria writes that Estalella was “a very light mulatto …white enough to play in the American League and in Organized Baseball.”38 Throughout his career in major-league baseball, questions about his ancestry were a shadow behind the headlines. Many of his teammates and a few prominent sportswriters of the era considered him to be black. Shirley Povich wrote that there was blatant racism: “Estalella was the first of the Cubans in the American League in a couple of decades and it was a tribute to him that he did hit .400 one season while ducking dust-off pitches from guys who didn’t cotton to his particular pigmentation.” Decades later, when asked to comment about it, Estalella simply answered, “It was only an issue for the Americans.”39

Estalella handed down his love of baseball to his son, Victor, and grandson Robert, who was a catcher for six major-league teams over a career that spanned 1996-2004. “The reason I wear my stirrups so high is because my grandfather did. It’s to honor his memory,” The younger Estalella said in 1998. “Up until last year I always wore No. 26 because that was his number. Then I reached a point where I knew I’d have to get a number [27] for myself. But still, I respect everything about my grandfather’s career.”

Roberto Estalella died on January 6, 1991, in Hialeah, Florida. when his grandson was a junior in high school. Selected by the Philadelphia Phillies in the 23rd round of the 1992 draft, Bobby said, “… and I know he knows what I’m doing.”40

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Other than those referenced in the endnotes, the author consulted the following sources:

Myrdal, Gunnar, An American Dilemma, Vol. I (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1944)

Wallace, Steve, “Jazz, Baseball, Life and other Ephemera.” wallacebass.com, May 2, 2013.

Silary, Ted, philly.com, August 4, 1998

Welch, Matt, “The Cuban Senators,” espn.com

Heuer, Robert, “Minnie,” chicagoreader.com

Graham Jr., Frank, “The Great Mexican War of 1946.” si.com

Notes

1# Robert Heuer, “Minnie,” chicagoreader.com, May 7, 1987.

2 Frishberg did not pronounce Estalella’s name correctly in the song; see his explanation in the BioProject biography of Dave Frishberg.

3 The Sporting News, November 17, 1938.

4 Roberto Gonzalez Echeverria, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 264.

5 The Sporting News, April 16, 1936.

6 The Sporting News, July 20, 1944. The fractured English was typical of the time.

7 Peter C. Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 119.

8 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 145.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Canton (Ohio) Repository, February 26, 1939.

12 Ibid.

13 New Orleans Times-Picayne, April 45, 1953.

14 The Sporting News, April 16, 1936.

15 Harrisburg Telegraph, October 19, 1935.

16 Harrisburg Telegraph, August 5, 1935.

17 Harrisburg Telegraph, August 9, 1935.

18 Richmond (Virginia) Times Dispatch, August 30, 1937.

19 Bjarkman, 331.

20 The Sporting News, April 27, 1939.

21 The Sporting News, February 23, 1939. Later that year, on December 2, in a game pitched for Havana by Luis Tiant (father of the major-league pitcher), Estalella hit a ball so deep to left field at La Tropical that, though his ball was caught, baserunner Frank Crespi tagged up and scored from second base, giving Tiant another run with which to work. See Echeverria, 265.

22 The Sporting News, April 27, 1939.

23 Ibid.

24 Richmond Times Dispatch, September 13, 1939.

25 Ibid.

26 The Sporting News, March 21, 1941.

27 Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, May 9, 1942.

28 Dallas Morning News, March 15, 1940.

29 Kansas City Star, April 6, 1943.

30 Richmond Times, March 24, 1944.

31 Ibid.

32 Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, May 16, 1944.

33 United Press, Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, September 19, 1945.

34 Ibid.

35 Baton Rouge Advocate, April 3, 1947.

36 Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 28, 1946.

37 Terre Haute Star, June 7, 1949.

38 Echeverria, 264.

39 Baseball-Reference.com.

40 Silary, Ted, philly.com, August 4, 1998.

Full Name

Roberto Estalella Ventoza

Born

April 25, 1911 at Cardenas, Matanzas (Cuba)

Died

January 6, 1991 at Hialeah, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.