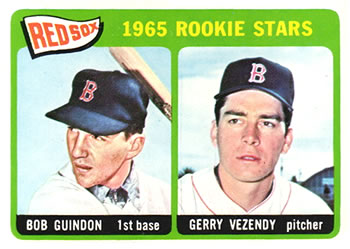

Bobby Guindon

Bobby Guindon’s major-league career spanned nine days in 1964, but he worked hard for six more years hoping for another shot, even converting from a first baseman/outfielder to a pitcher after a horrific encounter with a snow blower permanently hampered his ability to grip a baseball bat.

Bobby Guindon’s major-league career spanned nine days in 1964, but he worked hard for six more years hoping for another shot, even converting from a first baseman/outfielder to a pitcher after a horrific encounter with a snow blower permanently hampered his ability to grip a baseball bat.

Robert Joseph Guindon was born just down the street from Boston’s Fenway Park, in the bordering town of Brookline, Massachusetts, on September 4, 1943. His parents were Henry and Mary Guindon, and they had three other children — Henry Jr., Paul, and Marie. The family lived in Roslindale at the time, later moving to West Roxbury. Henry Guindon worked in the retail shoe business as a salesman for Coward Shoe. May Guindon was a homemaker, “a very, very good homemaker,” Bob Guindon said in a February 2018 interview. “She sewed at home and she also worked along with her sister, who owned a dress shop. And she also made curtains. She loved to sew. The shop was in the White City, a little area at the end of the MTA tracks around Forest Hills. It was kind of like a village within a village. It was a small area, with everyone involved with other families. All the parents and mothers knew exactly where their kids were and where the other kids were. It was just a nice place to live.”1

The Guindon parents discouraged him from playing sports. “Bobby had a blood disease when he was very young,” Mary Guindon said the day he signed with the Boston Red Sox, “and the doctor said he would never be able to engage in sports. Since then we were always worried. He was big for his age and had to play with the older boys and the field is far away from our house. We were afraid he’d get hurt and we wanted him to try for college instead.”2 He was indeed an all-scholastic honoree his last three years in high school.3

He had been discouraged from playing Little League when the family had first moved to the West Roxbury neighborhood of Boston because he was already large and strong for his age and local League officials felt he would overpower the other children.4

Bobby attended the Robert Gould Shaw School in West Roxbury and then Boston English High School. He played basketball and ran track, but by age 16, it was his baseball playing that was already attracting the attention of local scouts. He played first base for Boston English, and semipro ball in the summertime for the Malden City Club in the Suburban Twilight League. He led that league in home runs and RBIs in the summer of 1960.5

In 1960 he became the only player in the country to make the Hearst All-Stars two years in a row, one of the top 18 players selected in the six weeks of tryouts and games in the national competition. He was 15 years old at the time he played in the 1959 game at Yankee Stadium, which he believes made him the youngest player to appear in the national Hearst game.6 Wilbur Wood, also from the Boston area, was selected in 1959. Wood won the game and Guindon was 2-for-5 with a single and a double.

Manager Ossie Vitt predicted they’d be back at Yankee Stadium playing in big-league uniforms after they were old enough to sign. “They’re the two kids who came through when the pressure was on. We could have blown the game big, but with Wood pitching and Guindon coming up with that hit we broke through and it was all downhill from there.”7

One of his favorite days at the plate came in a game between English High and Watertown High School in 1960. “We were behind 8-2 entering the last of the ninth. I batted twice in the inning and hit consecutive homers to drive in five runs and we rallied to win.”8

A Boston Globe report said that Guindon came to Fenway Park for the 1960 Hearst trials limping due to a hurt ankle and figured he had no chance to make the team, but the left-handed youngster pulled three of the five pitches he was thrown into the bullpens in right field.9 He had struck out in the championship Hearst game at Yankee Stadium in the summer of 1960, but not before hitting three “foul ball homers” into the upper deck. At age 16, he was already 6-feet-1 and weighed 185 pounds; he later added another inch and is listed with a playing weight of 195 pounds. He attracted the attention of a number of former big-league players who took time out to help tutor him. “Mr. [Eddie] Waitkus has been wonderful to me,” Guindon said in July 1960. “He’s been out to every one of our games for three weeks and he gets out on the field during our practice and gives me advice [on fielding at first base.]”10

He was scouted heavily during his senior year at Boston English. He hit .538 in his final high school season. In the end, it was reported that 14 clubs made offers, each team representative given a half-hour to make his pitch to Bobby and his parents. The winning team was the Boston Red Sox, who offered a reported $135,000 signing bonus, which at the time was said to be $10,000 more than the largest bonus previously paid (to Lew Krausse of the Athletics two days earlier).11

Mary Guindon said, “We’ve always been Red Sox fans.” Bobby himself said they selected the Red Sox because, “they made the top offer and I’ve always wanted to play for them.” Mary Guindon added, “Naturally, we wanted him to be close to home and we’re glad that he’s going to be.”12

These were the years between the bonus rule and the major-league draft. There were no player agents yet. How did he know what to ask for? It turns out he didn’t know. Bob Guindon told the story at length in the February 2018 interview:

“My parents were hard-working people. They had no concept about working as a professional baseball player. My dad always felt as though it was a game. If it got in the way of school, you wouldn’t be able to play. They never watched any of my games, before the Hearst games at Yankee Stadium. They just had no idea. It was all a big surprise to them. They didn’t have any reason to come watch my games, or they just couldn’t.

“Four or five scouts started to call. They talked to my parents. They could talk to me back then, but that was useless because I didn’t know anything — what to say. They would talk to my parents and say they were very interested, and they would like to be considered, to make an offer to me for my contract when I graduated from high school. They [my parents] didn’t know what that meant.

“We had a friend of ours who was in the newspaper business, by the name of Ralph Wheeler. He was with the Globe, I think, and he was the high school reporter. He come over to the house once and talked to my mom and dad and said this was going to happen. The scouts are very interested in talking with you and making an offer. They asked, ‘What do we do?’ So he helped guide them a little of what to expect. He had some knowledge and it was his recommendation — by this time, there were 10 or 12 teams that wanted to bid on my contract. They were shocked. They said, ‘Well, we don’t know much about this. We don’t know how to handle it.’ Back then there was no attorneys involved, no agents. Nothing like that. He said, ‘Well, there’s a lot of interest. To make it easy for you people, and for them as well, set aside a day after graduation. Just pick a day, a day after or two days after, and give them each a half-hour or whatever they need – but keep it less than an hour — give them a time they can come out.’

“So they did. My dad was working all the time, but my mother would take those calls and set them up with their appointments. I don’t know what the hell is going on; I had no idea. As far as money was concerned, we were pretty excited because they were throwing around numbers of $10,000 or $15,000. My parents thought that was just crazy.”

Given the times, that was more than his father would ever make in a year as a shoe salesman.

“Oh, absolutely. It was crazy to even consider this. My dad was going to take the day off to make sure I got the right kind of support. There was about 13 or 14 clubs interested. They were all going to make an offer. They filled up the schedule.

“And then the night before they were all to come in, we had them calling us and canceling. Wishing us well. They were talking to my parents, obviously, saying how happy they were to have scouted me, what a nice boy I was, congratulations for bringing up a wonderful boy, ‘You people must be nice’ and ‘We wish you luck. Be very careful with the kind of money that you’re going to get.’ It was just too much for my parents. They started to believe that maybe — just maybe – it could be $10,000.

“The next day, they started to come in, and the first guy that come in, he was apologizing. He wanted to show up, to show his respects to my parents, but said, ‘My team is just not going to make an offer. We think he’s wonderful and yada, yada, but we’re just not going to be able to afford the kind of numbers that we hear are being passed around.’ He’s ready to walk out the door and my father asks, ‘You’re not going to say anything? Are you sure? You don’t want to leave us with some kind of number? Well, give us an idea.’ So he says, ‘I’ll tell you what, Sir. I’ll just give you a verbal offer. If you don’t get an offer over $35,000 today, you call this telephone number and I’ll be here in a half an hour.’ And he left. And my mother started bawling her eyes out.

“The whole day, my parents were very emotional. The Red Sox came in as the last team. I’m not going to mention the other teams. It doesn’t matter. But the Red Sox came in — this was Neil Mahoney — and said, ‘OK, we would love to have you. Mr. Yawkey has given me permission to offer you whatever you need for us to have you on our team. But we’re not interested in making this a bidding war. Just tell us, would you like to play for the Red Sox? If you really want to do that, then we’re very interested in having you.’ He asked me, ‘Do you want to play with the Red Sox?’ I said, ‘Yes, I do.’ He said, ‘OK, then tell us what it is that we have to match.’ My dad said, ‘It’s $125,000.’ Neil Mahoney almost fell off the couch. [laugh

“He said, ‘Hold on. I have to call back Mr. Yawkey. We expected it to be high but we had no idea it would be that high.’ It was the highest ever [highest bonus ever offered to that point in history]. It was just crazy.

“I had three other teams that had offered over $100,000. There was one other team that had offered me $125,000.

“I think there were some players [the Red Sox] had missed [just earlier] and I think the local press was giving them a little bit of a hard time about not showing as much interest in the local talent. I think they felt it would be smart not to pass on me at that point. I was that young. I was on all these all-star teams — national teams as well as state all-star teams for three years. So there I was, and it began.”

Guindon was assigned to play in Alpine, Texas, for the Sophomore League (Class D) Alpine Cowboys. In 1961, he got into 64 games playing first base, and hit .284 with 43 runs batted in. That winter he worked on a crew surveying for an engineering firm in Boston.

In the spring of 1962, Guindon went to spring training with the Boston Red Sox. He did indeed play closer to home in ‘62, in the New York-Penn League (also Class D) for the Olean Red Sox in Olean, New York. He played in 111 games and hit .320 with 37 homers and 121 RBIs. Guindon led the league in the latter two categories and was named Rookie of the Year. He had been the only unanimous selection to the league All-Star team.

That fall, he worked out in the outfield during the Florida Instructional League. Rico Petrocelli roomed with him and later said what Guindon had already acknowledged — that he felt a lot of pressure due to signing the large contract. He needed to forget that, Petrocelli said, “and play every day as though he didn’t have a dime for a cup of coffee. If he does that, he’ll make it big.”13

He had, as one might expect, taken a good deal of flak from other players, some good-naturedly and some likely with an edge, regarding the big bonus he’d been given. In spring training in 1962, he said a few years later, “When I got into the batting cage, they needled me pretty good. I couldn’t take it. I talked back to them fresh and acted like a pop=off.” He told one of them he’d wrap the bat around his neck. Another time, when he couldn’t even hit the ball out of the batting cage, “I stepped out and threw the bat all the way into the first base stands.” He confessed, “I think I pulled all that stuff because I thought I was another Ted Williams. I found out the hard way I wasn’t…There are times I wish that I never got the money. I mean that. Sometimes I wish I was just another kid that signed for nothing and that no one paid any attention to.”14 He let it be known that he’d lost 30 pounds during his time with Alpine, worried about shaping up to expectations.

Before 1963 spring training began, Guindon had asked not to train in Scottsdale with the Boston ball club, but to go to spring training with Boston’s Triple-A club, the Seattle Rainiers.15 He was assigned to play Double-A ball in 1963, for the Reading (Pennsylvania) Red Sox in the Eastern League. It was a down year; he played in 118 games but only hit .238 and drove in 56 runs. That fall he returned for more work in the Instructional League, and later said that he had learned a lot at Reading.

It was in 1963 that Bob married Patricia Dorsey. She lived is West Roxbury, too. “We knew each other for…forever, it seemed like. She was my sweetheart. I was hers.”

In 1964 he was assigned to Seattle and improved to .264 in the higher classification, with again 56 RBIs but with 20 homers. The Red Sox finished in eighth place in 1964, 27 games out of first, and had a decision to make as to whether or not to protect Guindon in the draft. The team wasn’t going anywhere so they figured they’d give him a look.

Guindon had a very busy couple of weeks. He was called up to the Red Sox on September 10. He joined the team, and became a father on September 14. Five days later, he had his major-league debut. “A very busy time, yes. A little bit of stress on my part. Of course, my wife had the biggest challenge. But, yeah, to have all that going on at once…and I was a kid…I had just turned 21 on the 4th.”16

Pattie and Bob’s son Christopher Guindon was joined about 2 ½ years later by Craig. “Christopher has two wonderful children, both girls. He lives in Houston. Craig lives in Dallas and he has two boys and a girl.”

His major-league debut came in the September 19 game against the visiting Minnesota Twins, pinch-running for Dick Stuart in the bottom of the seventh inning. The next batter up hit into the third out of the inning, and Guindon was replaced. The next day, he pinch-hit and drew a base on balls, but again languished on the base paths. He got a start on September 23 in Detroit, playing first base, and was 0-for-4 in the game with one strikeout. On the 26th, he pinch-ran again. On the 27th, still at Tiger Stadium, he got another start, this time playing left field. He struck out his first time up, and his second, but then stroked a double to left field in the top of the seventh off Joe Sparma. In top of the ninth, he got a fourth at-bat. There were two outs and the Red Sox were losing, 3-0. He struck out for the third time on the day. It proved to be his last appearance in a big-league game.

There was no way to know that at the time, and Guindon put in a lot of hard work over ensuing years hoping to make it to the majors again.

Playing the two positions, first base and left field, in the two games he had started, Guindon handled eight fielding chances without an error. He might have played more for the Red Sox, at first base, but Dick Stuart — the reigning American League RBI king — was in the hunt for the title again. Stuart finished with four RBIs fewer than Baltimore’s Brooks Robinson.

So Guindon finished the season with one base hit. That earned him a chapter in the book One Hit Wonders.17 “I only had one hit,” he said in 2018, “but I had two line drives that were caught. Those don’t count. You never see those in the stats, but if [those had dropped in] instead of being 1-for-8, you were 3-for-8 and all of a sudden the stats count.”

Guindon trained with the Red Sox at Scottsdale in 1965 and had a legitimate shot at the first-base job but came up short and was cut from the squad on April 5 and sent to Florida to join the Toronto Maple Leafs, Boston’s Triple-A club of the day. He had a very rough year. In early May he was obtained by the Seattle Angels, the Triple-A club of the California Angels, on option from the Red Sox. In 31 games, he batted just .207 with 14 RBIs.

On June 13 the Red Sox recalled him from Seattle, and placed him with Toronto after they brought Tony Horton up from Toronto to play in Boston. He had liked playing in Seattle, but now found himself with the Maple Leafs. He hit .206 with 24 RBIs in 83 games, more or less the same as he had hit in Seattle. On October 22, Boston sold his contract outright to Toronto, which made him subject to the minor-league draft. He was dejected. “I wish now I’d gone to college,” he said. With a wife and child, he was working in a clothing store and taking a real estate course.at night.18

He was, indeed, still quite young. Dick Williams, his manager in Toronto, said, “He was confused and wanted to quit after the season. But I told him he could be my first baseman next year. He’s only 21 and has all the equipment to be a good ball player.”19

Guindon started the season with Toronto, but didn’t fare that well at the plate, batting .225 after 78 games. At the start of August, he simply left the club and appeared to be missing, but he had spent a couple of days driving back to Boston. He let Neil Mahoney know that he wasn’t happy, that he wasn’t playing enough.20 It was worked out that he would play in Double A for the Pittsfield Red Sox. He got into 31 games and hit .330. But he was far from satisfied. He said he couldn’t play for an organization that didn’t really want him. “I still want to play baseball,” he said, “but I won’t play for the Red Sox. If they won’t release me, I’ll quit.” Sox GM Haywood Sullivan wasn’t pleased with the attitude. “As long as he feels that way, then we don’t want him. Yes, we’re trying to deal him off.”21

They didn’t trade him, tempers cooled, Mahoney offered some advice, and Guindon played for Pittsfield again in 1967, batting .242 in 80 games. But he also started trying his hand at pitching (even though he had never pitched before, even in high school), and was 2-0 with a 0.69 earned run average in four starts and four other pitching appearances. “I think Bobby can make it as a pitcher. I really do,” said Pittsfield manager Billy Gardner. “He’s got the arm and looks really good. Bob throws as good as any left-handed pitcher in this league. He has a heck of a slider, a good fork ball and a fast ball that really moves.”22

As it happened, over the winter of 1966-67, Guindon had caught his right hand in a snow blower and it had taken somewhere around 100 stitches to close the cuts on the two fingers which were damaged. He was late to spring training, and apparently couldn’t grip the bat quite the way he previously could. “I don’t have tendons there anymore,” he revealed a few years later.23 But his left hand was still good, and he proved he could pitch. He filled in during a stretch of makeup doubleheaders. He even threw a 5-0 seven-inning no-hitter in the first game of a doubleheader against York on August 25. Two runners reached base by way of walks.24

The Boston Red Sox won the American League pennant in 1967, under skipper Dick Williams. And Williams, who had managed Toronto when Guindon skipped out in ’66, said that Guindon would never play for the Red Sox if he had anything to say about it: “If Guindon comes, I leave.”25

Guindon stayed in the organization, though, for another year. He went back to Florida Instructional League that fall to work on his pitching (and worked in a combined no-hitter there), and then started 20 games for Pittsfield in 1968. He was 10-6 with a 2.46 ERA. Pittsfield won the Eastern League pennant that year.

In the December 2 minor-league draft, Tulsa selected Guindon from Pittsfield and he joined the St. Louis Cardinals system. He was assigned to the Arkansas Travelers (Double-A) in the Texas League. He didn’t get much mound work — only 21 innings — and was 1-1 with a 4.67 ERA, but the Travs had him play in 92 games at first base. He hit .281 in 113 games.

His final season in pro ball was with the Triple-A Tulsa Oilers in 1970. Again, he was used more as a position player, only working a total of six innings as a pitcher. He played in 53 games in the outfield and 23 at first base. He hit .276 with 44 RBIs. Guindon resigned after the season.

He had begun training to become a bank officer with a bank in Boston, in case baseball didn’t work out.

In his post-baseball career, Guindon earned exceptional success in business at a variety of different positions. During the offseasons he had worked doing outdoor surveying work for an engineering firm for 70 cents an hour. He went to school at night and got his real estate broker’s license, and spent two offseasons working for a real estate firm. Then he got the invitation to join State Street Bank and Trust in their advanced executive training program. When he saw that baseball wasn’t going to pan out for him, he already had this other opportunity available to him and he worked for State Street for three years after retiring as a ballplayer.

Another friend invited him to apply for a position with Wang Laboratories, and he started in sales for the rapidly-growing Massachusetts-based computer company. He worked for Wang for the next 14 years. From sales, he become involved in sales training, even working overseas. He then moved to Chicago as a district sales manager, then came back to Massachusetts to head up the company’s services department as the company moved more in the direction of providing services such as programming. He later became a regional vice president.

After 14 years, the Guindons bought a country inn in Jackson, New Hampshire — the Inn at Thorn Hill. They ran that for three years, then sold it. Another opportunity came up. “A friend of mine had been doing a wonderful job helping a small company grow. They reached a point where they needed to expand their executive group and reached out to me. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of Stephen R. Covey. He wrote The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. It sold over 20 million copies. He had a top executive training program. I went out and helped them grow and grow and grow, until we merged with another company about 15 years ago. And I retired. It worked out tremendously. We all were happy.” He had served as Chief Operating Officer and as Senior Vice President.

He and Pattie lived in Florida and enjoyed their retirement years. Guindon died at the age of 80 on October 26, 2023.

Looking back on his baseball career, Guindon said, “Ten years is a good run, isn’t it? My baseball career was full of challenges. But I enjoyed some wonderful years in the minor leagues. It was a great experience. I tried hard. We played hard. A lot of great things happened to me in baseball. I had my chances. I had a lot of chances. The Red Sox gave me chances. The Cardinals gave me chances. I played Triple A for a long time, and I guess I wasn’t good enough. I’m happy going to bed every night — and I have been since I left the game — feeling I did the best I could.”

Bob Guindon died peacefully surrounded by family in Venice, Florida on October 26, 2023.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by David Kritzler. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Guindon’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Author interview with Bob Guindon on February 23, 2018. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations attributed to Guindon come from this interview.

2 Will McDonough, “Sox Pay Top Bonus,” Boston Globe, June 10, 1961: 15.

3 Warren Walworth, “Sox Get Guindon With $135G Bonus,” Boston American, June 10, 1961: 3.

4 Red Hoffman, “Guindon Expects to Reach Majors by 1963,” Boston Traveler, June 10, 1961: 4.

5 Will McDonough, “Bird Dogs Flying to Hub Again,” Boston Globe, April 6,1961: 39.

6 Author interview.

7 Bill McSweeny, “Sandlot Aces Hits on B’way,” Boston American, August 19, 1959: 17.

8 Red Hoffman.

9 Art Ballou, “Bird Dogs Like Hub’s Guindon Like They Liked Elbie, Murphy,” Boston Globe, September 4, 1960: 54.

10 Pat Horne, “Waitkus Aids Hearst Star,” Boston American, July 27, 1960: 35.

11 Will McDonough, “Sox Pay Top Bonus.” His signing was credited to Red Sox farm director Neil Mahoney. See “Guindon Thrice Honored, HR Mark Within Reach,” Boston Globe, August 19, 1962: 75.

12 Ibid.

13 Ed Costello, “Murphy Case Tops Guindon,” Boston Herald, March 31, 1963: 200.

14 Will McDonough, “Guindon Poorer, Wiser Than in ’62,” Boston Globe, March 3, 1965: 21.

15 Hy Hurwitz, “Guindon Spurns Scottsdale Camp,” Boston Globe, February 13, 1963: 16.

16 Author interview. “She came back three weeks early. She wanted to stay and have the baby in Seattle. Her mother wanted her to come back. I had had some indication that I might be called up at the end of the year. Having a baby in Seattle alone and all that responsibility when I might go with the Red Sox, she didn’t want to do it but she agreed to come back early. We had an apartment in Foxborough. We had that lined up, to be able to move into that whenever we got back home.”

17 George Rose, One Hit Wonders (iUniverse, 2004). Second edition 2009 available at www.baseballwonders.com.

18 Tim Horgan, “Guindon, 22, At Crossroads,” Boston Traveler, October 22, 1965: 37.

19 Herb Ralby, “Toronto Players Seen Great Help to Sox,” Boston Globe, September 30, 1865: 50. Guindon was 22 at the time, but indeed quite young.

20 “Guindon in Boston, Future Still in Air,” Boston Globe, August 4, 1966: 41.

21 Tim Horgan, “Bonus Gone, Guindon Now Seeks Trade,” Boston Traveler, December 15, 1966: 41.

22 George Sullivan, “Guindon Fighting Back As Pitcher,” Boston Traveler, June 14, 1967: 53.

23 John Ferguson, “Home-Run Punch Not An Uppercut, Guindon Discovers,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1970: 33.

24 A good account of the no-hitter is provided by Roger O’Gara, “Guindon Glitters With A No-Hit Job,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1967: 35.

25 Larry Claflin, “O’Connell Feels Sox Draft Cupboard Bare,” Boston Record American, November 28, 1967: 42.

Full Name

Robert Joseph Guindon

Born

September 4, 1943 at Brookline, MA (USA)

Died

October 26, 2023 at Venice, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.