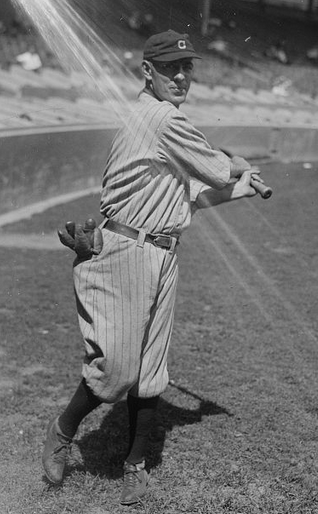

Braggo Roth

Bobby Roth, sometimes called Braggo, was an often insufferable self-promoter who bounced around among six American League teams in the years surrounding World War I, and was on the wrong side of two of the most lopsided trades of the Deadball Era. A player with diverse skills, Roth won a home run title and also stole home as many as six times in a season. But he was hampered by what one source called “the unhappy faculty of gaining enemies — apparently with cold deliberation.”

Bobby Roth, sometimes called Braggo, was an often insufferable self-promoter who bounced around among six American League teams in the years surrounding World War I, and was on the wrong side of two of the most lopsided trades of the Deadball Era. A player with diverse skills, Roth won a home run title and also stole home as many as six times in a season. But he was hampered by what one source called “the unhappy faculty of gaining enemies — apparently with cold deliberation.”

Robert Frank “Bobby” Roth was born in Chicago, Illinois, on August 28, 1892. For many years, baseball encyclopedias incorrectly listed Roth’s birthplace as Burlington, Wisconsin, where his parents spent several weeks each summer at the home of his mother’s brother, but he was actually born in Chicago. Situated on the banks of the Fox River, the tranquil village of Burlington did serve as a summer playground for Bobby during his childhood. Fourteen years in age separated Bobby from his older brother Frank, but the two shared a love of baseball, which was a pursuit encouraged by their father. Frank would enjoy a six-year career in the majors as a catcher, ending in 1910, but his claim to fame was the 36 home runs he belted in the Three-I League in 1901, a professional record at the time.

In 1910 when he was just 17 years old, Bobby signed his first professional contract with Green Bay of the Class-D Wisconsin-Illinois League. But after less than three months of underwhelming play, Roth was released and latched on with the Red Wing Manufacturers of the Minnesota-Wisconsin League (Class-D). The next season, with the Racine Belles, Roth displayed a strong throwing arm at third base, despite enough errant throws to accumulate 44 errors in 114 games.

Roth was a stocky 5’8″ right-handed batter, described as “small, but with fine forearms and the wrist action that poles a ball such long distances.” In 1912 he was optioned to St. Joseph, Missouri, of the Western League, where he played 39 games and made 14 errors at third. Four times that season his contract was bought and sold. His frequent travels from team to team earned him the nickname The Globetrotter.

In 1913, after being released twice, Roth caught on with the Virginia (Minnesota) Ore Diggers of the Class C Northern League. Roth improved his defense and hit .362 in just under two months of action, and his contract was purchased by the Class AA Kansas City Blues. He appeared in 123 games for the Blues in 1914, batting .293 with eight home runs and 91 runs scored. A quick runner, Roth earned a reputation as a “fleet-footed master” capable of “dismantling the enemy club with his spikes.”

Two important changes occurred in Kansas City in 1914 for Roth. First, he was made an outfielder by manager Bill Armour, former skipper of Cleveland and Detroit. Second, he earned a label that haunted him the rest of his career. In Kansas City, bolstered by his successes on the field, Roth began to acquire a taste for self-promotion. As author Tom Meany noted, Roth was “an entertaining talker and more often than not the hero of his stories was himself.” Based in large part on his boastful clubhouse attitude, Roth earned the nickname Braggo.

Helped by a recommendation from Armour, Roth was purchased by the White Sox in August of 1914. Playing regularly for the final month of the season, Roth performed well, hitting .294 in 34 games with six triples. In 1915 Roth switched to third base, where he stayed for the first six weeks of the season. “He has the range and judgment to track down flies, but his arm and glove work are needed at third,” manager Pants Rowland said. But Roth’s inconsistent defensive play, and the purchase of outfielder Eddie Murphy from the A’s, severely reduced Braggo’s playing time. On August 21 Chicago dealt Roth and two others to the Indians for Joe Jackson. As part of the swap, the Sox sent more than $30,000 in cash to Cleveland.

With Cleveland, Bobby struggled at first, but gradually his bat warmed up, as he hit .299 with an impressive .507 slugging mark in 39 games with the Indians to close out the 1915 campaign. Overall for the season, Roth ranked fifth in the league in slugging, third in triples, and eighth in OPS. Despite having been dealt for the popular Jackson, Cleveland fans took a liking to Braggo, who delighted them with flashy, though often unnecessary, diving catches. In the last week of the season, Roth slugged three homers to give him a total of seven, enough to edge Rube Oldring for the American League lead. Roth became the first man in the American League, and the first player since Bill Joyce in 1896, to capture a home run title while playing for more than one team. Ironically, the much-traveled Roth had hit all seven of his homers on the road.

On the eve of the 1916 season, Cleveland acquired center fielder Tris Speaker from the Red Sox, and Roth was nudged from center to right field, a position where he was far more comfortable. Batting in the cleanup position directly behind Speaker, Roth enjoyed a fine season, hitting .286 with 29 steals and four home runs. In April, Roth was at the center of an ugly incident at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. As an unruly partisan crowd grew strident during a lopsided game in their favor, fans began hurling objects onto the diamond. Roth was hit with a bottle, and retaliated by hurling the object back into the crowd. A ruckus ensued, which resulted in Roth’s ejection for his own safety. As a result, Roth became a villain in St. Louis and suffered taunting in that city for the remainder of his career.

In 1917, after a brief contract holdout, Roth displayed a different specialty, as he increased his stolen base total to 51, often swiping third on the front end of double steals with Bill Wambsganss. Though he was not credited with it at the time, Roth stole home six times in 1917, tying a major league mark. In 1918 Roth hit .283 in a season abbreviated by the war. Despite a back injury that plagued him most of the year and kept him from the Cleveland lineup for nearly three weeks, Bobby banged out 12 triples and was among the league leaders in extra-base hits and RBI. After a mediocre start the Indians inched to a second-place finish. Cleveland entered the off-season determined to acquire pitching. Their primary bait was Roth. With his talent for socking extra-base hits and swiping bases, Roth was coveted by nearly every team in the league. Eventually, it came down to the Yankees and the A’s, and Connie Mack won the sweepstakes, sending veteran third baseman Larry Gardner, pitcher-outfielder Charlie Jamieson, and pitcher Elmer Myers to the Indians for Roth.

Playing in right field and batting cleanup, Roth missed action early, suffering an injury in the first week of the season. Then in mid-May, Bobby shot his average above the .300 mark. The colorful Roth found it difficult to relate to the stoic Mack, however, and in short order Bobby was in the doghouse. More importantly, Mack was receiving offers from the Yankees and Red Sox, who still wanted Braggo in their uniform. Trying to turn around his franchise, Mack ignored Roth’s .323 average and 26 extra-base hits in 48 games and dealt Braggo to the Red Sox on June 27. The deal netted Mack both Amos Strunk and Jack Barry, two former A’s, although Barry retired when Mack refused his demand for a three-year contract.

The Red Sox moved Roth to center field, where he replaced Strunk and played alongside Babe Ruth, who was stationed in left when not pitching. In Boston The Globetrotter struggled, batting .256 with no homers, 23 RBI, and eight errors. The Red Sox slumped to sixth place and in the off-season dealt Roth to the Senators for three players. It was Braggo’s fourth team in less than two years. Playing under Clark Griffith in Washington in 1920, Roth was used in right field; he rebounded at the plate, batting .291 with nine homers, 92 RBI and 80 runs scored, all career bests. He also took more pitches, walking 75 times to post a .395 on-base percentage.

Despite Braggo’s fine season, Griffith dealt the outfielder to the Yankees on January 20, 1921 (one year to the day after he had been traded), for Duffy Lewis and George Mogridge. Like the Joe Jackson trade and the Charlie Jamieson deal, this trade proved one-sided for the team getting rid of Roth. Mogridge would play a key role on Griffith’s pennant-winning teams in the 1920s, as Shoeless Joe had helped the White Sox to two pennants, and Jamieson starred for Cleveland after having been dealt for Braggo.

With the Yankees in 1921, Bobby joined his older brother Frank, who served as New York’s pitching coach. Though Miller Huggins had tried to acquire Roth for nearly three years, the Yankee skipper showed little confidence in his new outfielder. Roth began the season in center, once again playing next to Ruth, but was benched after making three errors in the first few weeks of the season. Hampered by nagging injuries, Roth appeared in just 43 games for the Yankees, and was used primarily as a pinch-hitter in the last month of the season. In his eighth and final year in the big leagues, Roth batted .283 with 10 RBI and 29 runs scored, many of them as a pinch-runner. In January 1922, the Yankees released Roth, whose star had faded in quick fashion. Just a few years earlier, nearly every team in the AL had scrambled to acquire the hard-hitting outfielder, but after his 1921 season, no one wanted him. His failing legs were part of the reason, but his big mouth was a larger factor. The Reach Guide reported: “[Roth] is known as a tempermental [sic] player, who serves no club satisfactorily for any length of time.”

Just 29 years old in the spring of 1922, Roth found himself without a team and with few options. He spent the year in Burlington, playing sparingly for local semi-pro teams, before returning to the Kansas City Blues in 1923. The 1923 Blues were one of the greatest minor league teams of all-time, featuring sluggers Bunny Brief, Glenn Wright, Beals Becker, and Wilbur Good. Roth was hitting .339 for Kansas City when his stay with the club came to abrupt end on August 3, when Roth was released from the team for “indifferent play.” According to The Sporting News, “only with a hit in sight would [Roth] put his best leg power in motion and in the field it was a crime.” The Blues did not miss Roth’s contribution, going on to win 112 games. “There was a different atmosphere around the hotel lobby when Roth got his train out of Toledo,” The Sporting News observed. “To say that the members of the club are glad of his departure is to put it mildly.” The Kansas City Bulletin reported: “The Blues almost held a celebration when he was dropped.”

Despite the negative publicity surrounding his release by the Blues, a few weeks later Roth was signed by St. Paul, the team chasing Kansas City in the standings. With St. Paul, Roth hit .313 for the balance of the season, but could not help the club overtake his former teammates. In total, Roth had batted .324 in 133 games, scored 110 runs, with 32 doubles, eight triples, 12 home runs, 97 RBI, and 19 stolen bases. It would be his final season in professional baseball. In spite of his production, Roth was not invited back by St. Paul the following spring, having worn out his welcome once again. As the Kansas City Bulletin put it, Roth “was the exasperating grain of dust in the eye of whatever ballteam he became associated with.”

After spending several years playing for semi-pro teams in the Chicago area, in 1928 Roth reemerged with the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. Under his shaky 35-year-old legs, Roth played right field with limited range and effectiveness, appearing in 67 games. In his professional swan song, Braggo hit .283, but his foot speed and power had abandoned him: he hit just one home run and swiped a single base. He returned to Wisconsin and never played organized baseball again. On September 11, 1936, Roth was the passenger in a car driven by a friend when they were struck by an oncoming vehicle. Roth’s friend was killed instantly and Roth died later that day in a Chicago hospital from severe head injuries. He was 44 years old. Ironically for Roth, a man who had spent much of his life promoting himself, his car had been struck by a newspaper truck.

Note

A version of this biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Robert Frank Roth

Born

August 28, 1892 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

September 11, 1936 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.