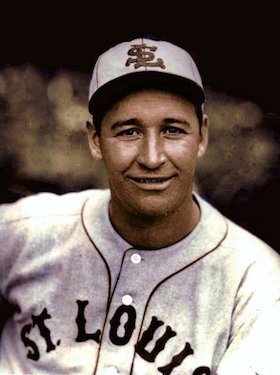

Bump Hadley

After three uncharacteristic second-place finishes in 1933, ’34, and ’35, the New York Yankees responded in decisive fashion. Changes were in order, as reported by Dan Daniel in The Sporting News: “Joe McCarthy is making every effort to win this year.”1 Significant personnel moves prior to the start of the1936 season included the signing of Joe DiMaggio and the acquisition of veteran pitcher Bump Hadley.

After three uncharacteristic second-place finishes in 1933, ’34, and ’35, the New York Yankees responded in decisive fashion. Changes were in order, as reported by Dan Daniel in The Sporting News: “Joe McCarthy is making every effort to win this year.”1 Significant personnel moves prior to the start of the1936 season included the signing of Joe DiMaggio and the acquisition of veteran pitcher Bump Hadley.

“McCarthy liked power pitchers,” a baseball historian has written. “Within reason, he was willing to put up with pitchers who did not have outstanding control.”2 This definition perfectly fit Hadley’s erratic career path to New York, where the right-hander became a valuable part of the (1936-39) dynasty.

Irving A. and Effie B. Hadley were of English ancestry and residents of Lynn, Massachusetts, when Irving Darius was born on July 5, 1904. Irving A. Hadley was a successful Boston area lawyer, and almost from the day the Hadleys’ only child was born, it was assumed he would earn a law degree and follow in his father’s footsteps.

Classmates at Lewis Elementary School couldn’t help but notice how young Irving resembled a husky contemporary comic-strip character named Bumpus. Friends started calling him Bumpus; the sobriquet soon evolved to Bump and was destined to last a lifetime.

At Lynn English High School, Hadley earned letters in baseball, basketball, track, rowing, and football – considered his top sport. Gridiron coach Bill Joyce not only admired Hadley’s offensive and defensive prowess, but also acknowledged him to be “the finest schoolboy punter on the north shore.”3 By graduation in 1923, the versatile Hadley set an interscholastic shot-put record, threw a no-hitter against Chelsea High School, and was drawing serious attention from college football scouts.

Hadley’s parents encouraged their son to enroll in a postgraduate program at Mercersburg Academy in south central Pennsylvania as preparation for Brown University and ultimately law school. After admission to the prep school in Pennsylvania, the right-handed-hitting Hadley became the starting third baseman, patrolled the outfield on occasion, and pitched when the need arose. After the team’s ace pitcher abruptly quit school, Bump took the mound and hurled a perfect game against the State Forestry School, on June 4, 1924. Of the 27 batters he faced, 26 went down on strikes; the lone batter not victimized tapped a weak grounder to third.

In the fall of 1924 Hadley entered Brown University. School officials assumed football would be his sport of choice; Bump surprised administrators by selecting baseball instead. Below-average grades hastened his departure from Brown during his sophomore year.

Signing on with East Douglas in the independent Boston Twilight League, the 5-foot-11, 190-pound Hadley and his live right arm produced an impressive 17-2 mark. The performance drew attention from a neighbor of sorts, former major-league pitcher and future Hall of Famer Jack Chesbro, who lived nearby.

Chesbro alerted his old teammate, former New York Highlanders manager Clark Griffith, to Hadley’s potential. Griffith trekked north and liked what he saw, comparing the hard-throwing Hadley to Walter Johnson. The Old Fox signed Bump to a Washington Nationals contract in the spring of 1926. As a football prospect, Hadley had been relatively ignored by baseball scouts, pleasing the thrifty Griffith, who didn’t have to fork over a large signing bonus.

The green-as-grass rookie made his major-league debut on April 20, 1926, in a relief appearance against the New York Yankees. Hadley quickly gave up five runs, three of them on a bases-loaded double stroked by Babe Ruth. Shuttled down to the Southern Association (Class A) Birmingham Barons, Hadley posted a 14-7 record with a 3.83 earned-run average.

Promoted back to Washington in 1927, Hadley became starter number three, finishing at 14-6 with an efficient 2.85 ERA. A serious case of mumps hospitalized the rookie late in the season. Teammates accompanied coach Nick Altrock, on a hospital visit. Altrock remarked, “You look funnier than me, you’re full of bumps, just as if you had been stepping into Johnson’s fast ball.”4 For the balance of the season, teammates referred to Hadley as Bumps.

Years later, Hadley reminisced about facing Babe Ruth during the Babe’s 60-home-run season of 1927. Bump was invited to visit Ruth’s posh New York apartment. Touring through Babe’s study, Hadley noticed a wall displaying photos of each pitcher who surrendered a 1927 dinger. Hadley was proud not to have given up a homer to the Bambino, but silently regretted being excluded from such an exclusive gallery.

Author Dick Farrington described Hadley as “an intelligent fellow, his speech shows culture and it is set off with a New England twang. He is personable and can smile easily and effectively. His hair is wavy brown and his eyes brown.”5 Apparently Hadley greatly impressed the former Jessica Gibbs, a Lynn native and his former high-school sweetheart; the couple married in 1927.

Despite a case of appendicitis in 1928, Hadley chalked up a 12-13 record with a 3.54 earned-run average. On September 3, 1928, he earned a footnote in the record books, surrendering a ninth-inning double to Philadelphia Athletics pinch-hitter Ty Cobb; it was the last hit in the storied career of the Georgia Peach. Washington won the contest, 6-1.

Walter Johnson became Washington skipper in 1929. Johnson painstakingly worked with the young hurler, instructing Hadley to mix pitches, keep hitters off balance and speed up his delivery. Hadley perspired heavily during the oppressive Washington summer heat, sometimes losing up to five pounds during a nine-inning contest. He slipped to a disappointing 6-16, with his ERA ballooning to 5.62.

That less than impressive season spurred Hadley to get an early start on spring training in 1930. That and improved conditioning helped him improve to a 15-11 record for the second-place Nats.

Hadley took exception when his next contract contained a weight clause, stipulating forfeiture of salary for tipping the scales at more than 195 pounds. A gym equipped with a rowing machine and stationary bike was added to his basement. “Working out in a gymnasium at his home in Lynn, Mass., the chunky chucker was minus the superfluous poundage he was usually burdened with after a winter of idleness,” The Sporting News reported.6

“Hadley has a world of stuff,” remarked Walter Johnson to Washington Post writer Shirley Povich.7 The pitcher was also admired from a distance by a sapient Joe McCarthy, the new manager of the New York Yankees. Marse Joe had a passion for hard throwers, especially those with the capability of starting or relieving. McCarthy offered veteran second baseman Tony Lazzeri for Hadley and infielder Jackie Hayes. The deal was later nixed by Griffith, after New York insisted on Buddy Myer instead of Hayes.i

Hadley remained a Nat in 1931, going 11-10, while sharpening his ERA to 3.06. He led American League pitchers with 55 mound appearances, starting 11 games and closing out 28, while tallying seven saves. A postseason trade indeed occurred on December 4, 1931, when Washington sent Hadley, Jackie Hayes, and Sad Sam Jones to the Chicago White Sox for pitcher John Kerr and outfielder Carl Reynolds.

Opening 1932 in a White Sox uniform, Hadley posted a 1-1 record before being dealt on April 27 with Bruce Campbell to the St. Louis Browns for Ralph “Red” Kress. Bump finished 13-20 with a 5.53 ERA under manager Bill Killefer. His 21 total losses, 149 earned runs surrendered, 171 walks and 8 hit batters were all league-leading figures. Hadley pretty much summed up his season in remarking to John Farrington: “Batters are all tough when you can’t put the ball where you want it.”9

In a June 1933 Baseball Magazine article, John L. Ward described Hadley’s repertoire: “Hadley’s stock in trade is his fastball, which is plenty fast. He pitches a few curves, but he has never developed a particularly serviceable bender. His change of pace is mainly a shift from a fast ball to a ball that isn’t quite as fast.”10. Browns catcher Muddy Ruel taught Hadley to relax on the mound, keep batters off stride, and not trying to strike out every hitter. Bump toiled a league-leading 316⅔ innings for the last-place Browns, going 15-20 with a 3.92 ERA.

Hadley’s start on June 6, 1934, against Washington at Griffith Stadium was an eerie precursor to an event in the pitcher’s future. With Washington leading 2-1 in the bottom of the third, an errant offering by Hadley struck the head of Nats catcher Luke Sewell.

Washington Post columnist Shirley Povich described the incident: “If I recall, before the ball hit, Hadley yelled – look out, but (Sewell) couldn’t duck. As he sagged to the ground, Hadley whitened in horror.”11 Manager Rogers Hornsby removed the still trembling Hadley, who later remarked, “I’ll never throw that side-armed curve again. I can’t control it. I’ll hit somebody bad.”12

Sewell recovered to play again that season. Hadley finished 10-16, helping the Browns improve to sixth place. Ironically, Hadley was traded back to Washington for Sewell (and cash) on January 19, 1935. Bump posted a 10-15 record, with a 4.92 ERA, for the 1935 Nats.

The Yankees and Joe McCarthy finally attained their goal of acquiring Hadley, on January 17, 1936. Washington packaged the pitcher with Roy Johnson for Jimmie DeShong and Jess Hill. Reporting to New York, Hadley was assigned to room with rookie prospect Joe DiMaggio; the two would remain lifelong friends. Hadley’s other pals in New York included hunting partner George Selkirk, New Hampshire native Red Rolfe, and future Hall of Famer Joe Gordon. Early speculation figured Hadley to be a member of the relief corps, but McCarthy had other ideas, assigning him to a starting role. Hadley compiled a very effective 14-4 record, good enough to post a league-leading winning percentage of .778.

The hard-charging 1936 Yankees won 102 games, finishing 19½ games ahead of the second-place Detroit Tigers. It was the first American League flag for the Yanks since 1932. The observant Hadley’s ability to steal the opposition’s signs was deemed a contributing factor to the club’s success. The Yankees won the World Series over the New York Giants in six games. Game Three at Yankee Stadium on October 3 was a classic pitchers’ duel, with Hadley besting Giants right-hander Freddie Fitzsimmons, 2-1.

The 1937 Yankees were first-place occupants when the third-place Detroit Tigers arrived at Yankee Stadium in late May for a three-game series. The pitching matchup on May 25 pitted Hadley against Schoolboy Rowe. Down 1-0, the Tigers tied the game in the third when Detroit player-manager Mickey Cochrane took a Hadley curveball deep.

Hadley faced the left-hand hitting Cochrane again in the fifth with one out, a runner on first, and the score still deadlocked at 1-1. With a 3-and-1 count, Hadley threw a fastball high and tight in the strike zone. “Cochrane froze as the ball continued at him,” a Cochrane biographer wrote. “Mickey did throw up his right arm to protect himself but it was too late. He slumped to the ground after the pitch struck him in the head.”13 Hadley desperately yelled seconds before Cochrane was hit and then joined Mickey’s teammates, carrying the struck batter off the field. Cochran suffered multiple skull fractures and a concussion. The crowd of more than 15,000 sat in stunned silence, as afternoon shadows began overtaking Yankee Stadium.

According to author Sid Mercer, Hadley steadfastly maintained that the pitch was not intended to be a beanball. “For some reason that I can’t explain, my fastball was taking off – sailing at times and behaving normally at other times. I can’t understand why Mickey didn’t get away from the one that hit him.” Hadley was downcast over the injury to Cochrane.”14 Some of the Detroit players thought Cochrane lost sight of it. He looked as if he would pull away and then it happened. Hadley remarked, “I’m grateful to Joe McCarthy for keeping me in there. It gave me a chance to settle myself.”15

“Hadley keenly felt the seriousness of the accident,” the New York Times reported. “He visited the hospital Tuesday night and again yesterday morning, trying to see Cochran. Detroit players were particularly outspoken, declaring the pitch was an accident.”16 Cochrane remained unconscious, lingering between life and death, for several days; his condition was considered doubtful at best. Mickey ultimately recovered; however, his playing days were over.

Cochrane later publicly absolved Hadley from any blame, remarking to Joe Williams of the New York World Telegram: “He’s not the type of a man who would throw at a batter’s head, and besides, why would any pitcher try to bean a batter with the count 3 and 1?”17 Cochrane considered Hadley to be among the elite hurlers in the league; a hard thrower – albeit lacking control. “Always works hard. Knows how to pitch, though sometimes his execution falls short.”18 “When Hadley next pitched in Detroit, on June 5, the crowd cheered (Hadley) to express the belief that he hadn’t dusted Cochrane,” Hadley’s biographer wrote.19

The 1937 Yankees repeated as AL champs, winning 102 games, 13 games ahead of the second-place Tigers. Hadley’s season totals included an 11-8 mark, with a 5.30 ERA. The club again prevailed over the New York Giants, winning the World Series in five games. Hadley started (and lost) Game Four to Giants lefty Carl Hubbell.

Relegated to the bullpen early in 1938, Hadley got a spot start on June 23 and beat the Cleveland Indians 8-6. His next start produced a decisive 13-1 victory over the Philadelphia Athletics, winning him a promotion back to the staring rotation. He scattered eight hits, defeating Washington 2-0, on the day Lou Gehrig played in consecutive game number 2,100. Season totals included a 9-8 record, with a 3.60 ERA. The Yankees won their third straight pennant and swept the Chicago Cubs in the 1938 World Series.

The Yanks made it four consecutive pennants, securing the 1939 American League flag with 106 wins – 17 games ahead of second-place Boston. Hadley ended 12-6, with a fine 2.98 ERA. In Game Three of the World Series he relieved a sore-armed Lefty Gomez in the second inning and held the Cincinnati Reds scoreless. The next day, New York swept the World Series at Crosley Field.

In 1940 Hadley slipped badly to 3-5, with a 5.74 ERA. Commenting on the club’s disappointing performance (the Yankees finished in third place as Detroit won the pennant), he remarked: “It was overconfidence following four straight championships and I suppose some of the players got the idea they were invincible. This feeling made it difficult to light the old spark again.” Hadley admitted to sportswriter Dan Daniel: “Don’t think I’m passing the buck, I was in the same boat with the rest.”20

On December 31, 1940, Hadley was sold to the New York Giants via the waiver route, marking the first-ever direct transaction between the rival New York ballclubs. Yankees GM Ed Barrow remarked, “I hate to see Hadley go, always one of my favorite ballplayers; however with so many youngsters coming up, we must make room.”21

Bump predicted he’d be a starter with the 1941Giants; he looked forward to spring training with his new club, marking the occasion by slimming down to 190 pounds. Hadley won his only decision as a Giant, before the Yankees curiously repurchased his contract on April 29, 1941, only to sell him a day later to the Philadelphia Athletics.

This odd circumstance was somewhat explained by Shirley Povich in the Washington Post. “Hadley is on the payroll of the American League publicity department as exhibiting for its official movie film, and the National League would scarcely permit one of its pitchers to promote good-will for the AL.”22 Hadley was 4-6 with a 5.01 ERA before the A’s released him at the end of the season.

The country was at war and with two young children at home, Hadley remained close in 1942, choosing to pitch semipro ball for the Fraser All-Stars, of Lynn. In an exhibition game benefiting the war-effort, Hadley took the mound against the Boston Braves and won a tidy four-hitter.

Boston radio station WBZ hired the affable Hadley in 1942 as a sports announcer; he went on to broadcast play-by-play for the Boston Braves. He later did color commentary for the Red Sox and produced his own TV sports show.

Jessica Hadley adjusted the antenna on the couple’s black and white TV, preparing to watch the premiere of her husband’s show in 1948. When he got home after the broadcast, a meager dinner awaited Bump: “My wife saw that first television appearance and decided then and there that if I’m going to appear on video regularly, my 220 must be slimmed down to about 185 pounds.”24

After baseball, Hadley worked as a paint salesman, represented a fuel oil company and sold office equipment. In the early 1960s he signed on as a scout for the Yankees. The family was residing in Swampscott, Massachusetts, near Lynn, when Hadley was hospitalized after an auto accident. Bump succumbed to a heart attack at Lynn hospital on February 15, 1963. The former pitcher was buried in Swampscott and was survived by his wife, Jessica; a son, Irving L. Hadley, stationed at West Point; and a daughter, Joan Stephenson.

Hearing the news of Hadley’s passing, former Washington teammate Joe Cronin called him “one of the greatest curve ball pitchers who ever lived.”25 A workhorse on the mound, the durable Hadley pitched over 200 innings seven times during his career, posting over 300 innings in 1933. He compiled a 161-165 lifetime record, toiling mostly for second-division clubs, with the notable exception being those four glorious seasons (1936-1939) pitching for the New York Yankees, considered by many baseball historians as one of the greatest dynasties of all time.

Sources

A special thank-you goes to the team at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library for scanning the contents of Hadley’s player file. Vital information was gleaned from baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, sabr.org/bioproject, and ancestry.com. The Sporting News, accessed through sabr.org and the Newspaper Archive, available through the Anne Arundel County (Maryland) library system, also provided pertinent details.

Notes

1 Dan Daniel, The Sporting News, January 23, 1936.

2 Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers (New York: Scribner, 1997), 96.

3 Boston Globe, February 6, 1963.

4 Fitchburg (Massachusetts) Sentinel, September 27, 1927.

5 Dick Farrington, undated article in Hadley’s file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York .

6 Denman Thompson, The Sporting News, January 29, 1931.

7 Shirley Povich, Washington Post, May 9, 1931.

8 Gary Sarnoff, The Wrecking Crew (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 74.

9 Dick Farrington, Sporting News, November 2, 1933.

10. John L. Ward, Baseball Magazine, June 1933; Rob Neyer and Bill James, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004).

11 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, May 26, 1937.

12 Ibid.

13 Charlie Bevis, Mickey Cochrane, The Life of a Baseball Hall of Fame Catcher (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998), 142.

14 New York Journal American, May 27, 1937.

15 Unidentified article in Hadley’s Hall of Fame File.

16 New York Times, May 27, 1937.

17 Joe Williams, New York World Telegram, June 26, 1937.

18 Stanley Frank, undated article in the New York Post.

19 Bevis, 143.

20 Dan Daniel, New York World Telegram, February 13, 1941.

21 John Drebinger, New York Times, January 1, 1941.

22 Shirley Povich, Washington Post, February 2, 1941.

24 Boston Globe, September 9, 1949.

25 Boston Herald, February 16, 1963.

Full Name

Irving Darius Hadley

Born

July 5, 1904 at Lynn, MA (USA)

Died

February 15, 1963 at Lynn, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.