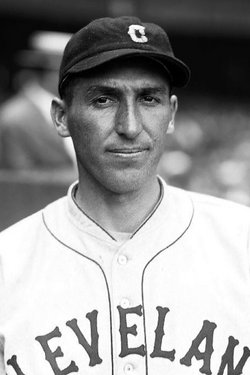

By Speece

The Cleveland Indians made their share of trading blunders even before 1960’s infamous Rocky Colavito for Harvey Kuenn debacle. In December 1924, the Washington Senators were looking for a veteran pitcher and the Tribe was in search of a good young right-hander. The two teams agreed to exchange future Hall of Famer Stan Coveleski for submarine hurler By Speece and spare outfielder Carr Smith. Coveleski went on to win 20 and lead the league in ERA for the pennant-winning 1925 Senators. Smith never played for Cleveland while Speece was gone by midseason in 1926 after 30 appearances with just three victories.

The Cleveland Indians made their share of trading blunders even before 1960’s infamous Rocky Colavito for Harvey Kuenn debacle. In December 1924, the Washington Senators were looking for a veteran pitcher and the Tribe was in search of a good young right-hander. The two teams agreed to exchange future Hall of Famer Stan Coveleski for submarine hurler By Speece and spare outfielder Carr Smith. Coveleski went on to win 20 and lead the league in ERA for the pennant-winning 1925 Senators. Smith never played for Cleveland while Speece was gone by midseason in 1926 after 30 appearances with just three victories.

In defense of the Cleveland front office, Coveleski was on the downside of his career and faded after his fine 1925 season. The hope was that Speece would become an important right-handed piece of the pitching staff that had more than its share of southpaws. His main asset was his control, which was “hard to acquire with such a delivery.” Compared favorably to Carl Mays, he became the top right-handed reliever on a Cleveland pitching staff that counted seven left-handers amongst their top ten most active hurlers in 1925.1

The following year, however, Speece was odd man out. Troubled by inconsistency thereafter, the only other time he spent in the majors was an ineffective 11-game stint with the Phillies in 1930. Yet he pitched on in the minors until 1945, when he was a remarkable 48 years old.

Byron Franklin Speece was a Hoosier, born in West Baden Springs, Indiana on January 6, 1897. His parents, Albert and Mary (McDonald) Speece, had five children; Byron was the youngest in the farming family. He listed himself as “American of Scotch-Indian” descent on the questionnaire he filed with the Cooperstown Hall of Fame in the early 1960s. To which tribe he could trace ancestry is unknown. His mother’s family hailed from central Ohio. His father’s lineage could be traced back to Virginia.

Speece grew to be quite athletic and played baseball and football growing up. Living near the French Lick Resort, he also learned the game of golf. He graduated from the West Baden schools and joined the work force before enlisting in the infantry in 1918. He stood 5’11” and weighed about 170 pounds as a 21-year-old. Over the years he would bulk up to 185 pounds.2

On April 13, 1921, Speece married Helen Grace Whittinghill, who was five years his junior. Grace was from the West Baden Springs area, but the marriage took place in Woodbury, Iowa. Speece had gone to the northwest corner of that state in 1920 when the town of Sheldon recruited him for their baseball team. The sponsors also provided him with a day job.

Speece’s performance with Sheldon caught the eye of Clifton “Runt” Marr, who recruited him for the Norfolk (Nebraska) Elk Horns, members of the Class D Nebraska State League. Speece debuted with a 3-2 win over Lincoln on May 12, 1922, delivering the winning run with a single in the ninth.3 With Marr leading the league in hitting and Speece winning 14 games and leading the team in innings pitched, the Elk Horns captured the second-half crown.

Speece’s first season in professional ball was marked by a couple of headline-making events. In June he was facing Pat O’Connor, the catcher for Fairbury. Byron delivered “a high curve and struck O’Connor behind and above the left ear.” O’Connor insisted he was not hurt but later that night his teammates found him unconscious in his room. He had to be hospitalized with a concussion but recovered and finished the season.4

On July 8, Norfolk was in Grand Island playing a game that quickly got out of hand because of the “crabbing and roughneckism of the Norfolk players.” Speece entered the game as a pinch-hitter and was playing outfield. In the ninth inning he assaulted the umpire and in turn was dragged aside by the angry crowd and “badly beaten up.”5

League President C.J. Miles was in attendance and immediately suspended Speece indefinitely. He also imposed a $50 fine. The local police, after rescuing Speece from the crowd, placed him under arrest. He was fined $25 by the local judge. Speece’s suspension lasted about 20 days.

In the postseason Norfolk faced the first-half champion Fairbury Jeffersons (also known as the Coyotes). The series went to seven games before Fairbury won. Speece struggled in his Game 3 start—getting pounded for 19 hits while his teammates made nine errors—leading to an 18-4 loss.6 In December Speece was sold to Omaha of the Class A Western League.

Omaha was managed by Ed Konetchy and featured a powerful lineup of veterans and up-and-coming players like Nick Cullop and Fresco Thompson. By then 26, Speece excelled on the mound and at bat. He went 26-14 in 314 innings and was ably supported by Buckshot May, who won 18 games. Speece batted .336 with a .504 slugging percentage. Despite his strong performance, the Buffalos (also called the Burchrods in honor of their owner, Barney Burch) finished in fourth place, well behind Oklahoma City.

Burch saw the scouts following Speece late in the 1923 season and set a $20,000 price tag for his services. Washington Senators scout Joe Engel was favorably impressed by Speece but thought the price tag too steep. Over the winter Pittsburgh offered two pitchers and $10,000 for Speece. On February 1, 1924, Clark Griffith of the Senators acquired Speece for shortstop Jimmy O’Neill, a pitcher to be named later (Fred Schemanske), and cash. The amount of money was not revealed at first, but “Griffith said it was ‘plenty.’”7

With spring training in Tampa, Florida just three days away, catcher Muddy Ruel and Speece had not returned signed contracts to Griffith. Both men signed soon after and Speece became one of a dozen rookies in the camp. Manager Bucky Harris gave Speece plenty of mound time but had issues with his work ethic and attitude. Harris issued a fine, but after Speece improved his “unfortunate disposition” and worked “earnestly,” it was rescinded.8

Washington broke camp and headed north with an improved pitching staff but otherwise seemingly few improvements over 1923. One local writer picked them for a fifth-place finish.9 The Senators would prove their detractors wrong by winning the pennant and the World Series.

Behind Walter Johnson the Senators opened the season with a shutout of Philadelphia. Speece debuted on April 21 in a 4-2 loss to the Yankees. He surrendered a hit in two innings of work. He claimed his first victory on April 27 in relief against Boston. Harris used Speece sparingly that season, giving him just one start and 20 relief outings for a total of 54 1/3 innings. Speece’s next decision was a win in Cleveland on September 18, when he hurled six strong innings of relief in a 9-5 victory. He got his only start on the final day of the season. He tossed six innings against the Red Sox, surrendering 12 hits. He made one of the seven Washington errors in the 13-1 loss. His ERA nudged up slightly to 2.65 because nine of his runs were unearned.

In the World Series Speece was called on just once, in Game Three. He allowed a run on three hits in an inning of work as the Giants triumphed, 6-4. The Senators took the crown in seven games to earn a parade before 100,000 adoring fans (Speece rode with Joe Judge and Firpo Marberry). The players earned just under $6,000 apiece for their accomplishment.

The Speece family now numbered four with the addition of Wilma (aka Irene) and Byron, Jr. They returned to Indiana for the winter. Speece had carpentry skills but it is unknown whether he worked that winter after the hefty World Series payday. His chance of earning another postseason payday in 1925 diminished greatly when he was traded to sixth-place Cleveland on December 12. As it turned out, the Indians finished sixth in the AL again the following year.

Despite his success as a starter at Omaha, Cleveland management also quickly decided that Speece was bullpen material. When throwing a pitch, he bent so low that he “used to scrape his cuticles on the ground every time he delivered.”10 Just when he decided to go with the unique style is unknown because it was reported he could pitch overhand. It is possible that an arm injury in 1920 precipitated the change but no corroboration has been uncovered. His style meant that a fastball was still rising as it approached the batter. He also had a sweeping curve.11

Speece picked up his first win for the Indians on May 15 with a fine three-and-one-third innings of relief against Boston. He also contributed a double and scored a run. His worst performance of the year came a month later in Philadelphia. Cleveland was ahead 15-4 when the Athletics staged a miraculous eighth-inning rally. Jake Miller was lifted with one out, up 15-6, and replaced by Speece—who promptly surrendered four consecutive singles. Carl Yowell relieved, giving up a single and walking one to make it 15-11. George Uhle was brought in and got the last two outs, but not before he allowed six runs (two charged to Yowell) to top off the 13-run rally that gave Philadelphia a 17-15 win.

On August 29 Speece was given the start against Boston. He responded with a 3-2 win as he scattered nine Boston hits. When doubleheaders started to pile up in September, he earned two more starts in Detroit and New York. He tossed complete games but lost each time (3-2 and 4-3).

Speece rejoined Cleveland in 1926 and was one of 12 pitchers who made the trip north out of training camp. The Indians had led the American League in complete games with 93 in 1925; well above the league average of 72. Speece had led the team in relief appearances with 25 while Garland Buckeye had the most by a lefty with 12. The 1926 starters increased their complete games to 96 while the league average dropped to 68. Buckeye was again the busiest lefty reliever, but Benn Karr took over as the top righty.

Speece made just two scoreless appearances, allowing a hit and walking two. When rosters had to be cut back, manager Tris Speaker let Speece be outrighted to the Indianapolis Indians in the American Association. He did not resurface in the majors for another four years.

Speece fit in nicely with the Indianapolis staff and won 17 games to match teammate Dutch Henry. Bill Burwell and Carmen Hill both won 21 for second-place Indianapolis. The Pittsburgh Pirates acquired the rights to Speece over the winter.

Speece went to the Pirates’ spring camp in California but developed a sore arm. On April 14, he was returned to Indianapolis. He won his first start, 11-3, over Milwaukee on April 24. He pitched in relief for a month before earning a spot in the rotation, but was plagued by inconsistency. Management soured on him and included him in a conditional trade with the Toledo Mud Hens for shortstop Bud Connolly. According to press reports he could be recalled by Indy after the season.12

Speece lost his first start for Toledo, then shut out Indianapolis on July 27 in a game shortened by a midsummer rainstorm. Again inconsistent, he closed out the year with a 12-10 record and a 4.14 ERA.13 Nonetheless, Indianapolis exercised its option and brought Speece back for the 1928 season. Used mainly in relief, he struggled and posted a 1-4 record with a 5.20 ERA for the league champions.

Indianapolis defeated the Rochester Red Wings five games to one in the Junior World Series. Speece saw action in Game Two, which was the Red Wings’ only victory. He tossed two scoreless innings.14 In 1929 he was used as a starter/reliever and regained good form. He posted a 9-2 record with a 3.80 ERA, drawing the attention of the pitching-starved Philadelphia Phillies, who drafted him.

Speece looked good in the Winter Haven camp with the Phillies and earned a spot on the roster as a reliever. Two weeks into the season the local paper labeled him the team’s “star relief slabman.” That was high praise for a man who had made two appearances and sported a 10.38 ERA. Unfortunately, he came down with influenza and was confined to the hospital with a fever of 102 while the team left on a western swing.15 He missed over three weeks of action before returning on May 21.

The 1930 Phillies pitching staff posted the worst numbers in the modern era (since 1901), ending with a 6.71 ERA and 1.847 WHIP. Speece proved to be inconsistent again. Two scoreless outings in June were followed by an 11-run debacle in Chicago. After retiring one batter and surrendering seven runs against New York on July 10, he was released. Speece had made 11 appearances with an ERA of 13.27. The Phillies surrendered double-digit runs in all his games.

Speece was signed by the Newark Bears in the International League and closed out the season in their bullpen. After posting an unsightly WHIP of 2.288 with Philadelphia, he reduced that to 1.021 with the Bears in 19 games. He remained with the Bears until June 1932, when he was sent to Nashville in the Southern Association.

The Nashville manager was Jo Jo Klugmann who had played with Speece in Cleveland. He was excited to have the submariner join his staff, especially since they had been overworked and a fresh arm was needed. Speece got his first start on June 27 in Little Rock and was breezing along until a pain in his side sent him to the bench. It was revealed after the game that Speece had sore ribs from a traffic accident.16

On July 10 he hurled the first shutout of the season for the Vols, beating Little Rock, 4-0, in seven innings. He added another shutout on August 5 over Memphis. He closed out the campaign at 9-6 and saw additional action as a pinch-hitter. He batted .246 with five doubles and two triples.

Speece found a home with the Vols. He tossed over 200 innings in each of the next four seasons and posted wins totals of 17, 22, 15, and 22. The 22 wins in 1936 led the league. Nashville was in the top echelon of the Southern Association but was unable to get past the first round of playoffs in each of Speece’s top seasons.

In total, Speece spent parts of seven seasons (1932-38) with the Volunteers. In addition to anchoring their staff, he served as a pinch-hitter and occasionally played the field. He went 137-for-541 (.253) at the plate for Nashville. He also developed into a talented fungo hitter. Pitchers were often used during warmups and practices to drill infielders and outfielders with practice balls. Speece could place the ball as needed and had the power to reach any part of the park. In his Indianapolis days he got into trouble for hitting home runs one-handed during practice when he should have been lofting flyballs for the outfielders to shag.17Indianapolis teammate Elmer Yoter proclaimed in later years that Speece was “the most accurate I ever saw.”18

His exploits on the mound, at bat, and as a coach led sportswriters to dub him “Lord” Byron Speece. He turned 40 before the 1937 season and showed signs of wearing out. He was not sent a contract in 1938 as the Vols attempted to sell him to another franchise. When no takers could be found, Speece reported to camp and prepared himself for a role as a reliever. In his first outing he finished the game with two scoreless innings; it would have been a save in today’s world, since Nashville won, 5-4.

Speece worked a seven-inning stint before he was released on May 1. Grace and the children were with him in Nashville. With his career and livelihood at a crossroads, Byron and Grace weighed their options before he decided to head to Buford, Georgia, to join the Bona Allen Shoemakers semipro club. This team had been to the national semipro tournament the last two seasons and had finished as national runners-up in 1937. Intent upon a title, they were known to pay $200 or $300 a month to a player. They also supplied offseason employment in the “shoe factory, harness shop or tannery.” 19 Whether the family moved to Georgia or Grace and the children returned to Indiana is unknown.

Speece was an instant success on the semipro level, winning his first six starts. Called upon to play the field because of injuries to teammates, he hit a double, triple, and home run in a 14-8 win on June 7.20 Bona Allen advanced to Wichita, Kansas, in August for the National Semi-Pro Tournament. They cruised through the preliminary round, then posted a 7-1 record in the final stage for the championship. Speece was named most valuable pitcher.21

The Bona Allen team won $5,000 for their victory and the funds were split amongst the players. Speece took his share and returned to Indiana, where he played semipro ball at a less intense level in 1939.

The following year Speece was enticed back into the professional ranks when the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League signed him. At 43 he was the oldest man on the roster.22

Speece spent three seasons with the Beavers, retiring in late July 1942. He had three different managers and the team never came close to challenging in a pennant race. He made 55 starts and 26 relief appearances over three seasons in the PCL and posted 25 wins. The family had left Indiana and was now settled in the Portland area. Speece put his carpentry skills to work with a company called Timber Structures, Inc.

In the winter of 1942-3, with World War II in full swing, he served as chairman of a fund drive to provide athletic equipment for the troops. The workers at Timber Structures contributed $450 “plus a considerable assortment of used gear.”23 Speece had planned on the 1942 season being his last in baseball, but when spring came, he hedged on that decision. Portland was loaded with pitchers and opted to sell Speece to the Seattle Rainiers on April 7.

The Rainiers were a much better team than Portland had been. They finished in third place in 1943, helped considerably by Speece’s 13 wins and 2.83 ERA. The following year, at age 47, he tossed 180 innings and spun 15 complete games while posting a career low 2.80 ERA. He retired partway through the 1945 season because of a bone chip in his elbow. He embraced his reputation as a Methuselah and patriarch, even joking that he wanted to pitch—and win—when he was 60. His plan was to gather two teams and have one last fling.24 There is no evidence that he followed through on that dream.

In retirement, Speece worked for Timber Structures and managed their company ballclub. He played a strong game of golf and enjoyed attending old-timers’ events. When he retired from Timber Structures, he and Grace left Portland and moved over 200 miles east to the small town of Elgin, Oregon where their daughter lived with her large family. He passed away there on September 29, 1974, and was buried in the Elgin Cemetery. Grace moved back to the West Baden Springs area, where she died in 1999. She was buried near Paoli, Indiana, in the Ames Chapel Cemetery.

The local Indiana newspaper ran a story in 1997 that Grace was the last surviving person associated with the 1924 Washington Senators. The claim was made that Speece struck out Babe Ruth when they faced one another. “That was a snap,” Grace remembered. “He got him out easy.”25 In truth, they faced each other seven times in two seasons. Indeed, Speece struck Ruth out twice while allowing just two singles.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Baseball Reference and Retrosheet were used for statistics and records unless noted otherwise. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball was consulted for standings and records.

Notes

1 Norman E. Brown, “A Blessing in Disguise,” News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio), January 4, 1925: 6.

2 As noted on his questionnaire in Cooperstown.

3 “Lincoln is Beaten in its First Game,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), May 13, 1922: 3.

4 “Fairbury Catcher Recovers,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Journal Star, June 20, 1922: 10.

5 “Game Ends in Small Riot,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), July 9, 1922: 7.

6 “Norfolk Wins Second State League Contest,” Omaha World-Journal, September 12, 1922: 13.

7 Frank H. Young, “Griffith Gets Pitcher from Western League,” Washington Post, February 2, 1924: 13

8 John B. Keller, “Harris Seeks to Bolster Attack of Nationals,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), March 26, 1924: 31.

9 N.W.Baxter, “Griff Entry Looks no Better than 1923 Except in Box,” Washington Post, April 1, 1924: S1

10 Tom Anderson, “From Up Close,” Knoxville Journal, June 1, 1959: 8.

11 Denman Thompson, “Battle Among National Rookie Hurlers Narrows: Costly Recruits Distributed,” Evening Star, May 5, 1924: 26.

12 “Byron Speece Goes to Toledo in Deal for Star Infielder,” Indianapolis Star, July 13, 1927: 14.

13 John B. Foster, ed., Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide (American Sports Publishing: New York, 1929), 193.

14 “Indians Backs up for Third Game,” Indianapolis News, September 29, 1928: 4.

15 “Phillies Spanked by Indianapolis Club,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 2, 1930: 22.

16 Blinkey Horn, From Bunker to Bleacher,” The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), June 30, 1932: 11.

17 The Indianapolis Star, May 28, 1927: 13.

18 Bob Beebe, “Fungo Hitters May be Fiends- But They’re Artists,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), March 29, 1959: 96.

19 Rebecca McCarthy, “That Championship Season,” Atlanta Constitution, May 8, 1988: 123,125. The Shoemakers reportedly had a 96-16 record in 1938.

20 “Buford Sweeps Riegals Series,” Atlanta Constitution, June 8, 1938: 10.

21 “Buford Takes U.S. Semipro Ball Title,” New Orleans States, August 29, 1938: 8.

22 Baseball-Reference lists Rudy Kallio, age 47, on the team but research by SABR member Bill Nowlin revealed that to be Rudy’s son.

23 “Timber Structures Employees Collect $450 for Equipment Drive; Albina Push Grows,” The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), February 14, 1943: 41.

24 L.H. Gregory, “Greg’s Gossip,” The Oregonian, May 14, 1951: 25.

25 Fred Smith, “In the News,” The Herald (Jasper, Indiana), February 14, 1997: 4.

Full Name

Byron Franklin Speece

Born

January 6, 1897 at West Baden Springs, IN (USA)

Died

September 29, 1974 at Elgin, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.