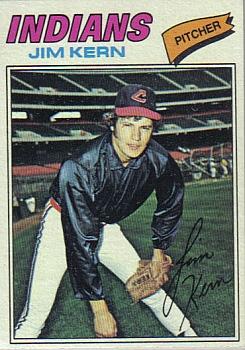

Jim Kern

For Jim Kern, the 1979 season was unlike any other he had experienced in the major leagues. Not only had he established himself as one of the top relief pitchers in baseball, but he was finally on a contending team. After years in Cleveland, where the organization’s perennial mantra was “wait until next year,” Kern was now the top pitcher out of the bullpen in Texas. And perhaps his value was never more evident than it was on July 4, 1979.

For Jim Kern, the 1979 season was unlike any other he had experienced in the major leagues. Not only had he established himself as one of the top relief pitchers in baseball, but he was finally on a contending team. After years in Cleveland, where the organization’s perennial mantra was “wait until next year,” Kern was now the top pitcher out of the bullpen in Texas. And perhaps his value was never more evident than it was on July 4, 1979.

The Rangers were hosting the Baltimore Orioles in a three-game set at Arlington Stadium beginning July 2. The O’s were on a 22-3 tear going back to June 6, and led Boston by 5½ games in the American League East. But Texas was no slouch. Since June 23, the team had posted an 8-1 record, with their only loss a 15-inning, 13-12 setback by Oakland. In the first game of the series with the O’s, Steve Comer beat Dennis Martinez as the Rangers won 2-0. The Rangers shut out the Orioles again in the second game, 4-0, behind Ferguson Jenkins, who tossed a one-hitter and fanned 10.

The third game pitted the Orioles’ Mike Flanagan against the Rangers’ rookie hurler Danny Darwin. Texas jumped all over Flanagan, scoring four runs in the bottom of the first inning and sending the Oriole southpaw to an early shower. However Darwin was having his troubles as well; the Rangers’ lead through five innings was only 7-5.

The Ranger bullpen was well rested thanks to the two complete-game shutouts by Comer and Jenkins. Kern entered the game in the sixth and struck out the side after giving up a single to Billy Smith. Texas then tacked on two runs in the bottom of the frame to extend the lead to 9-5. In the eighth inning, Kern surrendered a leadoff walk to John Lowenstein. No matter; Kern struck out the side again to strand Lowenstein.

The ninth inning showed Kern’s true mettle. He walked Al Bumbry and then gave up a double to right-center field to pinch-hitter Pat Kelly. With runners now on second and third, Kern bore down. He struck out Ken Singleton and Eddie Murray, then got Doug DeCinces to ground out to third base to end the game. Kern had pitched four innings, tying a career-high in strikeouts with nine, notching his 14th save and lowering his ERA to 1.38. With the 9-5 win, the Rangers climbed into a virtual tie with California for first place in the AL West. “What set this up tonight was the two shutouts earlier,” said Texas manager Pat Corrales. “Our bullpen was rested, and the rest helped Kern, obviously. A team like Baltimore is going to keep coming at you like they did tonight. They wouldn’t give in.”1

James Lester Kern was born on March 15, 1949 in Gladwin, Michigan. Kern lived in Midland, Michigan, where his father owned an upholstery business. His mother worked there as a seamstress. At 6’4” Kern was unusually tall for a high school freshman. But he weighed only 159 pounds and was, in his owns words, “a terrible athlete.”2 Kern was drawn more to participate in other outdoor sports such as hunting or fishing. For him, baseball was just a way to fill time. “I was always able to throw the ball through a cement block wall,” said Kern. “The only problem was, I could never hit the wall.”3

Baseball may have been just a hobby for Kern, but major league teams took notice when he fanned 43 batters in the final two games he pitched in the state high school baseball tournament when he was a senior. Cleveland signed him as a non-drafted free agent on September 4, 1967, giving him a $1,000 bonus.

Kern began a long and winding road through Cleveland’s farm system. Through his early career, there was no question that he could throw hard, with a whip-like motion that often had his fastball reaching 100 MPH. But throwing it consistently for strikes was another matter.

After a season in Rookie League ball and Class A in 1968, Kern enlisted in the United States Marine Corp. He ended up serving one year of active duty and five years in the Reserves. “I did a lot of growing up in the Marines,” said Kern. “I kind of found myself and decided I wanted to play baseball as a profession. That year let me look at baseball as an outsider.”4

He returned to the minor leagues in 1970. He was assigned to Class A Sumter of the West Carolinas League and spent some time with Class A Reno of the California League. He posted a 5-6 record in 17 starts between both teams. Although he totaled 91 strikeouts, Kern issued 90 free passes—far too many for that number of strikeouts. Clearly, Kern would need to better control his missile-like fast ball if he hoped to ever make it to the majors.

That year Kern married his high school sweetheart from Midland, the former Jan Gunkler. They eventually had three children, Jason, Ryan and Emily.

Kern spent the 1971 season with Reno, throwing a no-hitter on May 29 against San Jose. The game was only a seven-inning affair because it was the first game of a doubleheader. Kern struck out eight and walked only two in the abbreviated game. “I’ve lost games in the last inning and I didn’t want to lose this one,” said Kern. “I just wanted to keep them from getting a run.”5 But Kern was still struggling with his control, walking 100 batters against 109 strikeouts for the year.

It was when Kern was promoted to AA San Antonio of the Texas League in 1973 that he received some much-needed tutoring. Joe Horlen, who had been a pitcher for 12 years in the major leagues, played his last season in the majors in 1972 with Oakland. Horlen, a San Antonio native, joined the San Antonio Brewers as a player-coach. “The general manager in San Antonio asked Horlen to come out and pitch a few games for us,” said Kern, “just to draw more fans. Horlen pitched, but on his own he came out and helped me several times during the season.”

Kern went on, “He taught me so much. It’s a pleasure to watch someone like him work. He showed me how to make the ball sink a little or run a few inches away from the hitter, how to set up a hitter, just a lot of little things.”6

The help from Horlen yielded good results as Kern posted an 11-7 record for San Antonio with a 2.98 ERA in 1973. He totaled 182 strikeouts and 129 walks. The following year he went 17-7 with a 2.52 for Oklahoma City and was named the American Association Pitcher of the Year for 1974. No doubt because of the help he got from Horlen he had found his control, striking out 220 batters and issuing only 104 walks in 189 innings of work. His splendid mound work earned him a call-up to Cleveland, where he made his major league debut on September 6, 1974 against Baltimore. Kern went the distance in the 1-0 loss to the Orioles.

Kern earned a spot on Cleveland’s pitching staff in 1975. New skipper Frank Robinson placed Kern in the bullpen. But when Jim Perry started the year with a 1-5 record, Robinson moved him to the bullpen and Kern replaced him in the rotation. (Perry was subsequently traded to Oakland, on May 20).

Kern beat the California Angels and Frank Tanana by a score of 3-2 on May 21 for his first win in the big leagues. Then, when Cleveland traded Gaylord Perry to Texas on June 13 for Rick Waits, Jim Bibby and Jackie Brown, they sent Kern down to Oklahoma City in order to make room for the new pitchers. Kern eventually returned to Cleveland, but what was later diagnosed as tendinitis cropped up in his right shoulder. The injury ended his year.

The Indians were forming a competitive club in 1976. Newer players like Dennis Eckersley, Rick Manning, Duane Kuiper and Kern mixed in with veterans George Hendrick, Ray Fosse, Buddy Bell and Dave LaRoche to form a nucleus to build on. They finished the year with an 81-78 record, the first time the Tribe finished over .500 since 1968.

At first Robinson used Kern in long relief, and then moved him into the back end of the pen to pitch the later innings. With Kern, a righty, and LaRoche, a southpaw, Cleveland had a good one-two in its short relievers. “Jim has done an outstanding job for us,” said Robby,” he’s so much more valuable working out of the bullpen, though I know he can start if necessary. When I came to the Indians, everybody told me about Kern’s potential, but it seems that’s all they were able to talk about–his potential. The line on Jim always was the same–if he can throw strikes, there’s no doubt he can win in the big leagues. But the trouble always was that part about throwing strikes.”7

Perhaps the true value of having Jim Kern in its bullpen was displayed on May 23, 1976 when Cleveland hosted Milwaukee in a doubleheader. In the opener, Cleveland was clinging to a 2-1 lead going in the top of the ninth inning. With runners on first and second base, Kern came in to relieve LaRoche. He hit Bobby Darwin to load the bases. But then he settled down to get the next two batters to win for starter Jackie Brown. In the nightcap, Kern entered the game in the fourth inning after Cleveland starter Fritz Peterson gave up five runs in three innings. Kern shut the door on the Brewers the rest of the way, and Cleveland rallied to beat the Brewers 8-5 and complete the sweep.

Kern had a reputation as a jokester. He would routinely apply Vaseline to door knobs, give teammates the hot foot, and line their jockstraps with a heated liniment. Kern was generally described as a bit crazy, and he would often introduce himself that way. Once on a flight, a sportswriter was reading John Dean’s book Blind Ambition. Kern tore the book away from the unsuspecting writer, ripped out the last few pages and ate them. “Now figure out how it ends,” said Kern.8

But Kern himself read books on philosophy and anthropology, and he worked on a degree in chemical engineering at Michigan State University. He was given the nickname “Emu” after the tall, non-flying Australian bird similar to an ostrich. “The emu stuff began in 1976,” said Kern, “when Fritz Peterson and Pat Dobson were with us. One Sunday morning in the clubhouse they were working on a crossword puzzle, and I was doing my usual crazy stuff, running around crowing and flapping my arms. One of the clues in the crossword puzzle was the name of the world’s largest non-flying bird.”9 The answer of course was “emu” and Kern extended the moniker to the “Amazing Emu.”

Kern established himself as a top reliever in 1976. He posted a 10-7 record with a 2.37 ERA and 15 saves. In 117 2/3 innings pitched, Kern struck out 111 batters while walking only 50. His control had vastly improved since his minor league days. When LaRoche was traded to California in early 1977, the burden of closing games fell solely on Kern’s shoulders. Kern saved 18 games in 1977, and he was selected to the first of his three All-Star teams that summer.

Cleveland finished with a 69-90 record in 1978. Their pitching staff was dismal, as Rick Wise led the AL in losses with 19 and Mike Paxton was the only starter who finished with a winning record at 12-11. Kern finished with a 10-10 record and a 3.08 ERA. He saved 13 games as the Indians started to look to other arms in the bullpen. He was truly the lone bright spot of the entire pitching staff, and was the only Cleveland player to be selected to the All-Star Game.

But Sid Monge, who came over from California in the LaRoche deal, was being favored as the new closer for the Tribe. Thus, it was no surprise when Kern was dealt with infielder Larvell Blanks to the Texas Rangers for outfielder Bobby Bonds and pitcher Len Barker on October 3, 1978. Like many former Indians, Kern did not complain about leaving the losing culture in Cleveland: “In Cleveland, a successful year is playing .500. The manager and general manager come into the clubhouse have a meeting with the players, and what they say is ‘Play .500 ball’. I heard that every year I was there. You go to another club like the Rangers and nobody talks about .500. They talk about winning. We know we’ll be in contention. We know we have a chance.” 10

Kern had not liked the rules set forth by the Cleveland organization, such as not being allowed to wear jeans on the road and having to shave off his beard. “And then there was all that religion in the clubhouse. I know Andy Thornton is deeply religious, and I have nothing against that. He lives by what he preaches, and that impresses me. But there’s a time and place for everything. Essentially, you’re going out to do battle. The batter is trying to knock my head off with a line drive. You can’t preach ‘Love thy neighbor’ when you’re going out to try to beat the other fellow. The ballpark is simply not the place for it.”

The Texas air must have agreed with Kern. He was selected to the American League All-Star Team for the third consecutive season in 1979. Kern also was the recipient of the American League Rolaids Relief Pitcher of the Year Award in 1979. He led the Rangers in games pitched with 71. He went 13-5 with 29 saves with a miniscule ERA of 1.57. Sparky Lyle added 13 saves from the left side to give the Rangers a terrific 1-2 closing punch. However the team’s results were not as positive. The Rangers trailed California by two games at the All-Star break, but they lost 30 of their next 40 games to drop them into fourth place in the division and nine games off the pace. They would not recover.

But it sometimes happens to a player that after having a career year, there is a hangover. The 1980 season was a hangover one for Jim Kern. He battled neck and arm injuries and his production hit bottom. Danny Darwin was moved to the bullpen as both Kern and Lyle struggled. “There’s no question that Darwin is a starting pitcher and should be a starting pitcher right now,” said Texas manager Pat Corrales. “However, because we’re hurting so bad in the bullpen, we need him there. That’s why Kern getting straightened out is so important to this team. When Kern gets right, Darwin becomes a starter again. And the sooner that happens, the better off we’ll be.”11 When Kern developed a sore right elbow, he tried to compensate in his delivery. That caused him to feel pain in his right shoulder and damaged his vertebrae along with the velocity on his fastball. The pain was so much for Kern that he could barely turn his head. He went on the disabled list in August, essentially ending his year. He finished with a 3-11 record, two saves and a 4.83 ERA.

Kern’s list of ailments continued into the 1981 season. They included impacted vertebrae, neck spasms, a kidney stone, a hyper-extended elbow and atrophied muscles in the rotator cuff of his left arm. All of these impediments, in addition to a players’ strike that cancelled 713 major league games, caused Kern to pitch in only 23 games, the lowest total to that point in his career.

It was hardly a surprise when Texas traded Kern to the New York Mets for infielder Doug Flynn and pitcher Dan Boitano on December 11, 1981. Two months later, the Mets dealt Kern to Cincinnati along with pitcher Greg Harris and catcher Alex Trevino for George Foster.

Kern faced the same off-field issue in the Queen City that he did in Cleveland–the Reds demanded that their players shaved their beards. Kern fought the organization on this point. “There’s no rule (about beards),” said Kern. “There’s absolutely nothing about it in our rules and regulations.”12 Kern’s battle with the front office drew Marvin Miller, the Director of the Major League Players’ Association, into the discussion. Miller said that any such ruling was “quite absurd” in that day and age.

Reds’ skipper Russ Nixon was more concerned about the team, which finished 1982 in last place in NL West with a 61-101 record. But the distraction over Kern’s beard took care of itself when the Reds sent him to the Chicago White Sox on August 23, 1982 for two players to be named later.

After appearing in 50 games for Cincinnati and 13 more for Chicago in 1982, Kern threw out his arm in his lone appearance for the Sox in 1983. He had season-ending surgery to repair two torn muscles in his right forearm. It was a tough break for Kern, as the White Sox won the AL West that year. He missed out on his first opportunity to play in the post season.

Kern spent each of the next three years with a different team. After he was released by the White Sox in 1984, he signed on with Philadelphia that same year. But the Phillies released him on July 27, and he signed on with Milwaukee. The Brewers released him nearly a year later, on June 17, 1985. His career then came full circle when he signed with the Indians in 1986. But the Indians released him too, on June 17, 1986, and he retired from the major leagues.

In a total of 416 games, Kern compiled a record of 53-57 with an ERA of 3.32. He totaled 651 strikeouts and 444 walks.

Kern retired to Arlington, Texas after his playing career. In 1987 he began the Emu Outfitting Company. “I had been a hunter and fisherman all my life, so it was a natural extension for me,” said Kern. “We run hunting and fishing trips to Alaska, Zambia, South Africa, Uruguay, Argentina…actually almost any place you might want to go to hunt and fish.”13 Kern also stayed close to baseball; he worked for 12 years as a color commentator on college baseball games for FOX Sports Southwest.

Jim Kern was a competitor whose career was cut short by various injuries. He threw hard and played hard. But instead of just throwing hard, he learned how to pitch from veteran hurler Joe Horlen. Horlen taught Kern how to set up hitters, which Kern was apt to do with his fastball. But had a batter ever set him up? “Sure, Hank Aaron once set me up better than anybody ever did,” said Kern. “In an exhibition game I got behind Hank 2-1 then threw him a 95 MPH heater that he just looked sick swinging at. I said to myself ‘Damn, this old man is mine!’ I threw the same exact pitch and he hit the ball so hard off the center field wall that Rick Manning was able to hold him to a single. When I looked over at first, Hank was giving me this coy smile. I said about ten words under my breath that I can’t repeat, but they were all mumbled with respect.”14

This biography was reviewed by Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Randy Holloway, “Wills directs Ranger sweep of Orioles”, Dallas Morning News, July 5, 1979: 1B

2 Alan Greenberg, “Zany Kern having a ball in Texas”, Akron Beacon Journal, June 28, 1979: B1, Originally published in the Los Angeles Times, Date Unknown.

3 Ibid

4Steve Sneddon, “From My Corner”, Reno Evening Gazette, May 31, 1971: 14

5 Steve Sneddon, “Merrill’s Marauders keep win streak”, Reno Evening Gazette, May 31, 1971: 14

6 J. Carl Guymon, “89er Kern Pelts Opponents To Retain High Whiff Ratio, The Sporting News, July 6, 1971: 37

7 Russell Schneider, “Kern Pens Nifty Ditty in Tribe Bullpen, The Sporting News, July 17, 1976: 18

8 Alan Greenburg, “Flake: Jim Kern once ate half a Sporting News”, Los Angeles Globe-Democrat, June, 1979:

9 Russell Schneider, Whatever Happened to “Super Joe”?, Gray and Company, Cleveland, OH, 2007, 179

10 Hal Lebovitz, “Did ‘Heiden Effect’ Really Make Kern?’, Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 7, 1980: 1C

11 Randy Holloway, “Kern, Lyle Fade Away, Rangers Do the Same”, The Sporting News, August 2, 1980: 21

12 Peter King, “Miller Says Reds’ Policy ‘Absurd’”, Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1982: E1

13 Schneider, Whatever Happened to “Super Joe”?: 180

14 Stephen Hanks, “Interview: Jim Kern”, Baseball Magazine, June 1980: 32

Full Name

James Lester Kern

Born

March 15, 1949 at Gladwin, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.