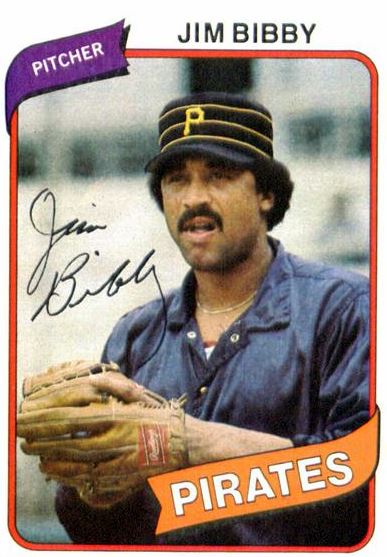

Jim Bibby

Everything about Jim Bibby was big. His frame: 6’5” and 235 pounds, with “legs like oak trees.”1 His hands: he could fit eight baseballs in his right hand — palm down — one more even than Sandy Koufax and Johnny Bench.2 His fastball: “vicious … serious heat … would scare the bejesus out of most batters.”3 His appetite: as his older brother Fred said, “Jim’s the only guy I’ve ever known who has to have two plates in front of him. One for meat, one for greens.”4 And most of all, his heart — so many fond memories flowed in after he died in 2010.

Everything about Jim Bibby was big. His frame: 6’5” and 235 pounds, with “legs like oak trees.”1 His hands: he could fit eight baseballs in his right hand — palm down — one more even than Sandy Koufax and Johnny Bench.2 His fastball: “vicious … serious heat … would scare the bejesus out of most batters.”3 His appetite: as his older brother Fred said, “Jim’s the only guy I’ve ever known who has to have two plates in front of him. One for meat, one for greens.”4 And most of all, his heart — so many fond memories flowed in after he died in 2010.

The burly righthander didn’t make it to the majors until he was nearly 28. He was wild, and it took him time and effort to harness his ability. His development was also delayed because he missed three full seasons in the minors — two in Vietnam and one after a back operation. Yet eventually he won 111 games as a big-leaguer (against 101 losses). He was an important part of the staff for the World Series champions of 1979, the Pittsburgh Pirates “Fam-a-lee.” He followed up with his career year in 1980, at the age of 35.

After his big-league career ended in 1984, Bibby spent 16 years as a minor-league pitching coach — 15 of them in Lynchburg, Virginia, the area where he lived much of his life. He also pitched in the Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1990. Upon his death, the Lynchburg Hillcats issued a statement saying, “Bibby was a foundation for baseball in the Lynchburg area, an institution in the Carolina League and his #26 is the only retired number in Lynchburg baseball history. Anyone who knew Bibby would tell you, you could not find a more jovial soul.”5

James Blair Bibby was born on October 29, 1944 in Franklinton, North Carolina. This small town is in Franklin County, in the north-central part of the Tar Heel State. Jim was one of three brothers in a family headed by Charlie Bibby and his wife, Evelyn Stallings Bibby. After Frederick and James came Henry Bibby, who went on to fame in basketball. In college at UCLA, under the great coach John Wooden, Henry was the point guard for three straight NCAA championship teams from 1970 to 1972. As a rookie in the NBA, he was a reserve for the New York Knicks, who won the 1973 championship. His playing days ended in 1981 after nine seasons, and he then went on to a long career as a coach. Henry Bibby’s son Mike played in the NBA from 1998 through 2012.

In 1981, Rick Telander of Sports Illustrated wrote an in-depth feature about Jim and Henry, providing much detail about their early lives and subsequent careers. They and Fred grew up on a farm in Franklinton.6 Bibby described it in his own words the previous year, talking with Dan Donovan of The Pittsburgh Press. “My dad owns his own farm and it’s 150 acres. The three boys, we all had a lot of work to do with the tobacco, corn, cotton, the animals. There was no need to lift weights. Farm work’s terrible — I hate it — but we were never poor. We had everything we wanted — we never had to make ends meet. We had everything you buy at the store now, only it was better.

“We always had time to play baseball and basketball. Some of the other kids didn’t have time because of all the work we had to do. But whenever it was time to play baseball, my dad would always say, ‘Go ahead.’” 7

Jim went to Franklinton High School, which “wasn’t big enough to field a football team,” he told Donovan. “We graduated 26 people my senior year. We had all the grades, elementary school through senior high, in one building. We were small, but we always had good sports teams in both baseball and basketball.”8

Bibby then followed brother Fred to Fayetteville State University in North Carolina, about 90 miles from home. Fred was a basketball star at FSU, eventually becoming a member of its athletic Hall of Fame. He helped Jim obtain a basketball scholarship too.9 Yet while Jim had great size, his true talent was not on the hardwood. As Henry Bibby told Rick Telander in 1981, “Jim was a hot dog, the 11th man. He’d get in a game, look up in the stands, score two points and think it was a big deal.”10

During the 1965 summer break from FSU, Bibby was told about a New York Mets tryout camp near his home town. He got to throw only a few pitches before the rain came and he was sent home. Yet later he got a call to come to the club’s rookie-league team in Marion, Virginia, where he signed for no bonus but started his career.11 That team included another fireballing righty, Nolan Ryan. “I just threw one fastball after another and I was always wild,” said Bibby in 1981. “Neither one of us knew a damn thing about baseball. We were both ungodly wild.”12 In 13 games that season, Bibby walked 27 batters in 24 innings, fueling an 11.25 ERA.

At the end of Bibby’s first pro season, the U.S. Army drafted him and shipped him to Vietnam, where he served as a truck driver. Returning in 1967 to Fort Lee, Virginia, he picked up with his second love, basketball, playing on the post team with NBA star Lou Hudson. Discharged in January 1968, Bibby returned to baseball with the Mets’ Carolina League team (Class A) in Raleigh-Durham. In 23 games (19 starts), he posted a 7-7 record and improved his control to a degree (74 walks in 131 innings). He had 118 strikeouts and a 2.82 ERA.

Bibby’s showing with Raleigh-Durham was impressive enough for him to attend spring training with the big club in 1969. He impressed manager Gil Hodges and pitching coach Rube Walker with his strength, staying power, and stuff. Walker also thought that control would come over time. Jim himself said, “I don’t really know how good I am — or if I’m any good at all. I’ve never pitched against really tough competition.”13

The Mets assigned their prospect to Double-A Memphis. After a 3-5 start, he finished 10-6 with a 3.32 ERA for the Blues, striking out 115 and walking 57 in 122 innings. As he had hoped in camp, the hot streak won him promotion to the Mets’ top farm club, Tidewater in the International League, in July 1969. He went 4-4, 3.48 in 11 starts for the Tides, who won the IL regular-season pennant but then lost in the first round of playoffs to Columbus.

The Mets then called up Bibby, and though he didn’t get to appear in a game for the eventual World Series champions, he was part of the celebration as the team clinched the National League East. Video footage shows an exuberant Jim and teammate Amos Otis up on the interview platform along with Mets broadcaster Lindsey Nelson. Bibby remained with the club as a batting-practice pitcher while they beat Atlanta in the playoffs. For his services, he received $100.14

During spring training with the Mets in 1970, Bibby’s “back, weakened by a congenital bone spur, gave out one day as he was covering first base.”15 The injury was initially reported as a “strain” or “sprain” but it was a lot more serious. Spinal fusion surgery was required, and “he was given a 50-50 chance of playing again.”16

After his surgery, Bibby missed the entire 1970 season with the Mets. Rehabilitation and hard work enabled him to come back strong with Tidewater in 1971 with 15 wins and 6 losses (and an ERA of 4.04 due to 109 walks in 176 innings). That August, The Sporting News featured Bibby as he hoped for another call-up to the majors. He said, “I wonder what more the Mets want me to do or show. I feel I’ve proved myself down here, and remember I’ve already had my share of waiting.”17

Although the Mets did recall Bibby again that September, he never did get into a game with them. On October 18, 1971, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in an eight-player trade, which was dismissed at the time as a minor deal. Out of all the players involved, in retrospect Bibby clearly had the most upside. Perhaps the Mets — at that time viewed as a pitching-rich organization — thought they could afford to deal a player who was nearly 27, unproven and with control problems. At the time, beat writer Jack Lang said, “The sale of Jim Bibby came as no surprise. The big guy throws hard but that’s about all.”18

Yet as Lang pointed out that November — even before the Mets made the infamous Nolan Ryan trade — the club’s pitching depth was not actually that great. Jerry Koosman was then battling injuries and Jon Matlack was the lone prime prospect.19 One wonders if Bibby was included in the trade over the objections of Whitey Herzog, then the farm director for New York.

In the winter of 1971-1972, Bibby played his only season of winter ball in Puerto Rico. He spent most of the 1972 season with the Cardinals’ top farm club, Tulsa, Oklahoma in the American Association. He had a very good year, going 13-9 with a 3.09 ERA, while striking out 208 (and walking just 76) in 195 innings. The Cardinals called him up after the rosters expanded in September, and he made six starts, winning his debut — which was actually his least impressive performance — but losing his last three.

The Cardinals used Bibby just six times with poor results in the early part of the 1973 season before dealing him to the Texas Rangers on June 6 for Mike Nagy and John Wockenfuss. Whitey Herzog, who had become the manager in Texas after leaving the Mets organization, was instrumental in the deal. In his fifth outing for the Rangers, Bibby threw a one-hit shutout at home against Kansas City. The only hit was a sixth-inning double off the wall by Fran Healy. Herzog said after the game, “I’ve known Bibby for four or five years and he has never lacked talent. I thought he was a good risk when I picked him up. I didn’t give up anything and I was desperate for pitching help.”20

Yet the righty’s best outing of the year was a no-hitter (the first in Rangers history) in Oakland on July 30. Bibby threw 148 pitches in his gem, nearly all fastballs, as he struck out 13 and walked six. “You couldn’t dig in against him because he was wild,” said Reggie Jackson. “He’s close to Nolan Ryan.” Sal Bando concurred, saying, “That’s the first time I’ve seen Bibby and I hope it’s the last.” A’s manager Dick Williams added, “Damn he was quick. He was conveniently wild. He did a heck of a job. I can’t get upset.”21

The last out was a looper into right center, which Texas beat writer Mike Shropshire called “a ball that I had seen the Rangers misplay with numbing frequency.” Yet while Vic Harris did ram into second baseman Dave Nelson, Nelson hung on to preserve the no-hitter. Catcher Dick Billings said, “The big guy was absolutely unbelievable. I don’t think there is a man in baseball who could have touched some of those pitches. I’ve never seen smoke like that.”22

Bibby — who was known for sweating buckets when he pitched — said afterward, “I bet I lost ten pounds by the time it was over. But I’m gonna get it all back in the clubhouse with some of that good cold beer and I’m ready for it right now.”23 As another reward, club owner Bob Short gave him a $5,000 raise on the spot.

The big man finished the season at 9-10, 3.24 for the Rangers, a dreadful club that got Whitey Herzog fired in early September. In 1974, Billy Martin (who had taken over as skipper) lifted the Rangers to second place. Bibby posted a 19-19 record in 41 starts, though his 4.74 ERA was a sign of inconsistency — he still didn’t have much besides his fastball. Author Joe Posnanski broke down the extremes of hot and cold in his Bibby retrospective of February 2010. “In his 19 victories, he had a 2.50 ERA and the league hit .194 against him. In his 19 losses, he had a 9.23 ERA and the league hit .359 against him.”24

Posnanski added, “The rest of his career was not quite so up and down, not quite the same blend of brilliant and disastrous. But Jim Bibby always seemed to carry a part of 1974 with him. It seemed like most days when he went out there to pitch, a team would say ‘Oh man, we don’t stand a chance tonight.’ Trouble is, you never knew which team.”25

Bibby’s social awareness was on display in a July 1975 article in Texas Monthly. Writer Paul Burka, who followed the Rangers for a week earlier that season, got into a conversation with Jim on a bus ride. “Baseball, Bibby said, is a white man’s game — not on the playing field, but in the stands. Black people don’t come to the ballpark, and it bothers him.” They went on to exchange various theories about how this came to be.26

Bibby’s social awareness was on display in a July 1975 article in Texas Monthly. Writer Paul Burka, who followed the Rangers for a week earlier that season, got into a conversation with Jim on a bus ride. “Baseball, Bibby said, is a white man’s game — not on the playing field, but in the stands. Black people don’t come to the ballpark, and it bothers him.” They went on to exchange various theories about how this came to be.26

After a 2-6, 5.00 start, Bibby was traded that June (along with Jackie Brown, Rick Waits and $100,000) to the Cleveland Indians for Gaylord Perry. As the Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia noted, “The financially strapped Indians. . .also cleared the air in the clubhouse, as Perry did not get along with manager Frank Robinson.”27

During his two-plus seasons with the Indians — who were then actually mediocre, not terrible on the field — Bibby won 30 and lost 29 with a 3.36 ERA. He was a swingman, starting 61 games and relieving in 34 others. Indians pitching coach Harvey Haddix helped him greatly with his delivery. As Haddix told Rick Telander, “It’s very hard for a big man to be coordinated. Jim was never in control of himself. For someone like Jim, with hands that size. . .well, it’s like you or me trying to throw a golf ball accurately.”28

Joe Posnanski said, “Bibby pitched his guts out for the Indians, especially in ’77. I loved Bibby. Big, wild, overpowering, frustrating, scary, larger than life.”29 In August 2011 Posnanski also told another funny anecdote that he heard from Duane Kuiper, Bibby’s Cleveland teammate. Kuiper was furious with Rod Carew of the Twins after Carew had slashed him while breaking up a double play. “Don’t worry,” Bibby said. “I’ll get him for you.” However, the opportunity did not arise until years later — in an exhibition game in Japan. Bibby drilled Carew in the ribs with his fastball, flexed, and said, “That was for Duane Kuiper.”30

Bibby’s time as an Indian was also productive off the field. He went back to school at Lynchburg College and obtained a degree in physical education, graduating with the class of 1977.

Bibby left Cleveland for the same reason he arrived. The Indians Encyclopedia said, “Lack of ready cash also cost the Indians the service of Jim Bibby, which was then unfairly blamed on [general manager Phil] Seghi. Because the team was late in paying Bibby a $10,000 incentive bonus he’d won in 1977, he was declared a free agent and was lost to the Tribe.”31 Cleveland sportswriter Terry Pluto added, “Bibby had to continually bug the front office for the bonus he was owed from the 1976 season, so this time he was really running out of patience.”32

On March 15, 1978, nine days after arbitrator Alexander Porter upheld Bibby’s breach of contract grievance, the pitcher signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He had other offers, but even though the money in Pittsburgh wasn’t the best — an estimated $700,000 over an unspecified multi-year contract — he liked the Pirates because they were not too far from his home in Virginia. He also rightly noted, “The team has good potential and can go places.”33

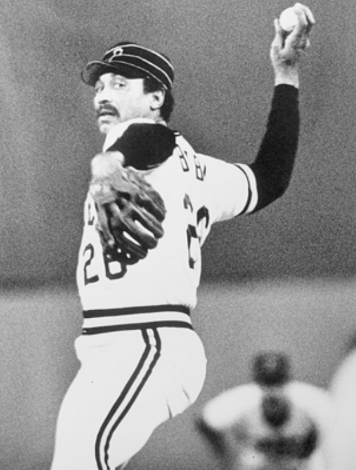

Manager Chuck Tanner continued to use Bibby as a swingman. In 1978, he started 14 games out of 34 appearances, and in 1979 he started 17 games and relieved in the same number. Harvey Haddix had come over from Cleveland starting in 1979 and he helped keep Bibby’s delivery smooth. Haddix said, “If he hadn’t wanted it real bad, he’d have been a goner. You don’t hang on in the big leagues because you look good in uniform.”34 Bibby was 12-4 with a 2.81 ERA for the ’79 champions. He also hit two of his five career home runs that year; Big Jim hit only .148 in the big leagues, but as The Pirates Encyclopedia put it, he could drive a ball a long way when he connected.35

The “Fam-a-lee” clubhouse was a boisterous place, and as Rick Telander observed, Bibby “fit in nicely, giving and taking insults with the best.” He’d also shown his fun-loving side in Texas, where he used the stage name “Fontay O’Rooney.”36 Yet he was also a serious man who sincerely cared about his teammates’ personal well-being.37

In the playoffs against Cincinnati, Bibby started one game. He then started two more in the World Series against the Orioles, including Game Seven. He had no decisions but pitched effectively, allowing just four earned runs in 17 1/3 innings.

That was the only time Bibby ever got to the postseason, though. The Pirates fell back to third in the NL East in 1980 — despite his best year ever. Moving back into the starting rotation (he relieved just once all year), he tied his career high with in wins with 19, and since he lost just 6, his .760 winning percentage led the NL. Jim was named to the All-Star team for the only time in his career; he finished in third in the voting for the Cy Young Award (behind Steve Carlton and Jerry Reuss). “I’m not raring back and throwing hard all the time,” he said that May. “I only do it when I have to.”38

The 1981 season featured another of Bibby’s most brilliant performances — he thought it surpassed his no-hitter. On May 19, he threw his other big-league one-hitter, and it was nearly a perfect game. At Three Rivers Stadium against Atlanta, Terry Harper’s bloop single to right led off the game — but after that, not another Brave reached base. “I was more consistent tonight than in my no-hitter,” said Bibby, who threw just 93 pitches that night.39

However, Bibby’s year was interrupted not only by baseball’s strike but also by injury. He made only four starts after the strike ended. He underwent surgery for a slight tear in his rotator cuff on April 21, 1982 — bone fragments were also removed from his shoulder. He missed the entire season, though he was able to throw on the sidelines in September. In January 1983, he expressed optimism about his comeback.40 As it turned out, though, he had a poor year: 5-12, 6.69 in just 78 innings pitched. He got into the seventh inning in just two of his starts. As Chuck Tanner noted that May, “Bibby was throwing hard. It was just a matter of location.”41

In November 1983, the Pirates allowed Bibby to become a free agent. He signed with the Rangers in early February 1984, again sounding upbeat. “I feel that I’m 100 percent right now. I don’t know if I’m going to throw as hard as I did when I was a rookie in Texas but I’m more of a pitcher now. I have a repertoire of pitches that I can put over the plate. I felt good physically last year. My mechanics were a little off.”42

Bibby made the club out of spring training, but relieved in just eight games before Texas released him on June 1. Eight days later, he signed as a free agent with the St. Louis organization. He appeared in two games for Louisville, their top farm club, but even though he allowed just two hits in five innings and did not give up any runs, the Cardinals released him on July 1. The U.S. Olympic squad had also hit him hard in a game on June 17. “I saw a lot of good players on that team,” said Jim.43 The hitters included Mark McGwire, Will Clark, Barry Larkin, and B.J. Surhoff.

That wasn’t quite Bibby’s last professional action on the mound, though. During the fall and winter of 1989-90, when the Senior Professional Baseball Association held its only full season, he joined the Winter Haven Super Sox. He pitched 54 2/3 innings in 11 games, going 2-4 with a 4.12 ERA.

In July 1984, Bibby went directly into coaching, starting with the Durham Bulls in North Carolina. He learned of a vacancy for the 1985 season in Lynchburg, near his home in Madison Heights, Virginia, which he pursued. He thus could enjoy full-time family life while still working and giving to his love, baseball. From 1985 through 1999, he was pitching coach for Lynchburg. The franchise was affiliated with the Mets (1985-87), Red Sox (1988-94), and thereafter the Pirates. Among the notable future major-leaguers he coached were Aaron Sele, Kris Benson, and Frankie Rodriguez. In 2002, after Lynchburg retired his number, he said, “When I see guys make it to the bigs and have success there, that’s more gratifying to me than anything else.”44

In 2000, Bibby stepped up to Pittsburgh’s top affiliate, Nashville in the Pacific Coast League. After that season, his contract was not renewed, he underwent double knee replacement surgery, and so retired. Though his knees weren’t up to throwing BP and hitting fungoes after more than 30 years on the field, he still often got out to games in Lynchburg.45

Among his other leisure pursuits, golf was Bibby’s favorite. In October 2011, his wife Jackie (they were married in 1968) and daughters Tanya and Tamara staged the first Jim Bibby Golf Classic at his club, Colonial Hills Golf Course in Forest, Virginia. The tournament was under the aegis of the James “Jim” Bibby Memorial Foundation, the non-profit organization that his family created “to continue Jim’s initiatives for supporting organizations and programs promoting fitness and health and wellness.” Proceeds of the tournament went to benefit two of his favorite causes, the YMCA of Central Virginia and the Children’s Miracle Network.46

Bibby was a longstanding member of First Baptist Church of Coolwell in Amherst. He was also active in his community. In addition to serving on the board of the Lynchburg YMCA and acting as an ambassador for the Children’s Miracle Network, he was an advocate for the Sickle Cell Foundation. He was also a loyal supporter of both the Jerry Lewis Labor Day Telethons and the American Cancer Society’s Relay For Life.47

After battling bone cancer, Jim Bibby died on February 16, 2010. At his memorial service, his friend Susan Landergan, CEO of the Lynchburg YMCA, said, “Big heart, big body, big talent, big personality, big hands, big humor, big hugs. Bibby lived life big.”48

This biography appears in “When Pops Led the Family: The 1979 Pitttsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Gregory H. Wolf.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Tamara and Jackie Bibby for their help and input.

Sources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.lynchburg.edu

Notes

1 Shropshire, Mike. Seasons in Hell. New York, NY: Dutton Books, 1996: 39.

2 Telander, Rick. “He’s Not Hot Stuff, He’s My Brother.” Sports Illustrated, March 2, 1981. “For the Record.” Sports Illustrated, March 1, 2010.

3 Shropshire, op. cit., loc. cit.

4 Telander, op. cit.

5 “Lynchburg Legend Jim Bibby Dies at 65.” Lynchburg Hillcats website, February 17, 2010 (http://lynchburg.hillcats.milb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20100217&content_id=8086010&vkey=news_t481&fext=.jsp&sid=t481)

6 Telander, op. cit.

7 Donovan, Dan. “Pirates’ Bibby Becoming BIG Factor.” The Pittsburgh Press, May 15, 1980: C-1.

8 Ibid.

9 An article in the Fayetteville Observer, published shortly after Jim Bibby’s death, alludes to the pitcher’s purported baseball career at Fayetteville State University. However, the Bibby family regards this account as inaccurate. See Batten, Sammy. “Jim Bibby (1944-2010).” February 19, 2010.

10 Telander, op. cit.

11 The scout was Bill Herring, a North Carolinian who had pitched and managed in various minor leagues in the area.

12 Telander, op. cit.

13 Girard, Fred. “Rookie Bibby Makes Pitch For Mets Job.” St. Petersburg Times, March 4, 1969: 3-C.

14 “Pennant Playoffs Sweetened World Series Pot.” The Sporting News, November 29, 1969: 34.

15 Telander, op. cit.

16 Telander, op. cit.

17 McClelland, George. “Bibby Impatiently Awaits Mets’ Next Distress Signal.” The Sporting News, August 7, 1971: 43.

18 Lang, Jack. “Mets Dump Ex-Heroes, Seek Slugger.” The Sporting News, November 6, 1971: 50.

19 Lang, Jack. “Met Rep as Pitcher-Rich Club Just Doesn’t Tally.” The Sporting News, November 13, 1971: 45.

20 Rothenberg, Fred. “Bibby Pitches 1-Hitter.” Associated Press, June 30, 1973.

21 “No-Hitter Bibby ‘Close to Ryan.’” Associated Press, August 1, 1973. “Bibby was also once a Met.” Associated Press, July 31, 1973.

22 Shropshire, op. cit.: 106.

23 Ibid., loc. cit.

24 Posnanski, Joe. “The biggest pitcher I ever saw.” Sports Illustrated, February 18, 2010.

25 Ibid.

26 Burka, Paul. “If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Oakland.” Texas Monthly, July 1975: 88.

27 Schneider, Russell. The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004: 235.

28 Telander, op. cit.

29 Posnanski, op. cit.

30 Posnanski, Joe. “That Was for Duane Kuiper.” Joe Posnanski’s “Curiously Long Posts” blog on the Sports Illustrated website (http://joeposnanski.si.com/2011/08/18/that-was-for-duane-kuiper/). This game probably took place in November 1979, as part of an All-Star series between the National League and American League. A combined American squad also faced Japanese players in two games.

31 Schneider, op. cit.: 380.

32 Pluto, Terry. The Curse of Rocky Colavito. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994: 195.

33 Feeney, Charley. “Bibby, at Start, Booked for Buccos’ Bullpen.” The Sporting News, April 1, 1978: 45.

34 Telander, op. cit.

35 Finoli, David and Bill Rainer. The Pirates Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2003: 363.

36 Shropshire, op. cit.: 39.

37 Telander, op. cit.

38 Donovan, op. cit.

39 Feeney, Charley. “Harper’s leadoff single ruins bid at perfect game.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 20, 1981: 17.

40 Feeney, Charley. “Bibby Feels He’s Set for Comeback.” The Sporting News, January 24, 1983: 40.

41 Feeney, Charley. “McWilliams Adds Strength, Deception.” The Sporting News, May 16, 1983: 18.

42 Reeves, Jim. “Bibby, 39, Rejoins Rangers.” The Sporting News, February 20, 1984: 42.

43 “Olympians Impress Bibby.” The Sporting News, July 9, 1984: 37.

44 Winston, Lisa. “Longtime player and coach honored.” USA Today Baseball Weekly, July 10, 2002.

45 Ibid.

46 Press release for Jim Bibby Memorial Golf Classic, July 7, 2011.

47 “James Blair ‘Jim’ Bibby.” Lynchburg News & Advance, February 19, 2010.

48 Thompson, Dave. “Mourners remember Jim Bibby’s big personality, care for community.” Lynchburg News & Advance, February 21, 2010.

Full Name

James Blair Bibby

Born

October 29, 1944 at Franklinton, NC (USA)

Died

February 16, 2010 at Lynchburg, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.