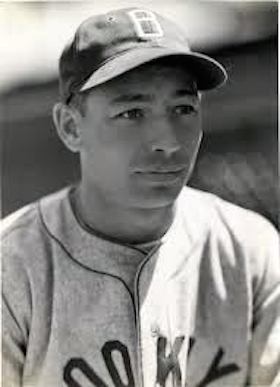

Gibby Brack

In 1937 rookie outfielder Gibby Brack captured the imagination of the baseball world with a 12-game hitting streak in the first two weeks of his major-league career, topping the National League in hitting. “There is power in his swing and speed in his legs,” exclaimed The Sporting News. “[H]e started out to make good for the Dodgers with a breathless drive that suggested [St. Louis Cardinals All Star outfielder] Pepper Martin … [Through July Brack was] far and away the best and most consistent hitter on the [Brooklyn] club.”1 Reportedly 24 years old, the right-handed hitter maintained a .300 average into August.

In 1937 rookie outfielder Gibby Brack captured the imagination of the baseball world with a 12-game hitting streak in the first two weeks of his major-league career, topping the National League in hitting. “There is power in his swing and speed in his legs,” exclaimed The Sporting News. “[H]e started out to make good for the Dodgers with a breathless drive that suggested [St. Louis Cardinals All Star outfielder] Pepper Martin … [Through July Brack was] far and away the best and most consistent hitter on the [Brooklyn] club.”1 Reportedly 24 years old, the right-handed hitter maintained a .300 average into August.

But all was not as it appeared. Brack was much older: a margin of five years that was successfully disguised throughout his entire career (a deception he perpetuated further with the 1940 US census takers). Brack was seemingly a sure bet for The Sporting News’ 1937 postseason all-rookie roster, but his severe second-half slump and a near-circuit-high 93 strikeouts blocked his inclusion. Though he exhibited power and speed in the minors, Brack never developed these assets fully in the major leagues. On December 4, 1939, after a year-plus with the Philadelphia Phillies, he was sold to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association. He never resurfaced, spending nine more years in the minors. On January 20, 1960, faced with the twin challenges of unemployment and despondency over the serious illness of his wife, Brack took his own life.

Gilbert Herman “Gibby” Brack was born on March 29, 1908, in Chicago. He was the last of 12 (step) children of Charles F. Brack through the father’s three (possibly four) marriages. In 1880, 23-year-old Charles immigrated to the United States from northeastern Germany and took up carpentry. Seventeen years later he married Gibby’s mother, Friedericke Schenk, also a German immigrant. Gibby grew up in Chicago’s 27th Ward, about three miles from the site of the present Wrigley Field. (He was 6 when the famed ballpark, originally dubbed Weeghman Park, was built.) Little is known of his education except its brief duration; he quit school after the eighth grade. The 1930 US census listed Gibby as a laundry bagger living with his parents.

But Brack’s sights were set far beyond an environment of washing and ironing. He secured a tryout with the Spencer Coals, a semipro club in the Chicago City League that had launched the professional careers of Milt Galatzer, Ed Linke, Wally Millies, Bob Weiland, and Phil Weintraub among others. In 1931 (and possibly the year before) Brack batted over .400 while working behind the plate for the Coals. The next year he entered the professional ranks with the Asheville (North Carolina) Tourists of the Piedmont League.

There is no evidence of a scout signing Brack to a contract, seemingly indicating he earned a roster spot through a tryout. The confidence gained by one season in Class B spurred Brack to set his sights even higher. In 1933 the 25-year-old successfully passed himself off as 20 and earned a brief stint with the Louisville Colonels of the Double-A American Association. But Brack’s slight build – 5-feet-9, 170 pounds – worked against him as a catcher. He was released and urged to develop at another position. In November the Colonels projected that Brack “perhaps could make the grade as [a] utility outfielder.”2

But the ambitious Brack had no intention of settling for a utility role. In 1934 he wrestled the right-field job away from all contenders and became a mainstay in the outfield corner for three years. (At some point during his run Brack moved to Louisville and spent at least one offseason working for the Hillerich & Bradsby Louisville Slugger plant.) In July 1935 Brack attracted major-league attention after a 27-game hitting streak hoisted his average to a near-league-leading .373. “[He] is nothing less than a natural,” claimed Bill Neal, the Colonels’ vice president and business manager. “Brack can hit, field, run, has baseball brains, can throw, and is hard as a pine knot and never sick.”3 Initially a line-drive hitter – Brack led the American Association in triples in 1935 – he gradually developed some pop as well. In 1936 Brack was the only player to hit a homer in every ballpark in the league while placing among the league leaders with 22 home runs,4 16 triples and 298 total bases. He also added 28 stolen bases to this impressive résumé. “[Brack] is one of the fastest right-handed hitters I ever have seen,” said Louisville manager Burleigh Grimes.5 The only downside to Brack’s season was The Sporting News’ report of a league-record 108 strikeouts. (That it was a record may be incorrect; another source indicates that Milwaukee Brewers outfielder Chet Laabs may have whiffed as many as 136 times that season.)

Having Grimes as his manager in 1936 worked out for Brack. The last-place Brooklyn Dodgers hired Ol’ Stubblebeard as manager to replace Casey Stengel, who had been fired at the end of the season.6 Grimes insisted upon taking Brack with him. Competing in spring training with five others for three outfield spots, Brack was initially anointed as the Dodgers’ center fielder before a severe sprained ankle suffered in an intrasquad game sidelined him for two weeks. Fortunately for him, just before the season opener Brack’s closest center-field competition, 36-year-old Johnny Cooney, was hospitalized with influenza.

On April 23, 1937, Brack made his major-league debut, against Phillies’ right-hander Bucky Walters in Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl. The leadoff hitter scored one run and collected two hits (including a triple) off the future NL Most Valuable Player in a come-from-behind 4-3 win. In his home debut, three days later, Brack greeted the Ebbets Field devotees with four hits in a losing effort against the Boston Braves. With a batting average that dipped below .400 just once through May 13, Brack stood atop the league in hitting. His offensive surge figured in a Dodgers four-game win streak, their longest in two years. On May 11, in the midst of a 7-for-17 run, Brack collected his first major-league home run in a 9-7 win over the St. Louis Cardinals.

But beginning on June 15 the shine began to lose its luster. A baserunning blunder in Cincinnati drew much criticism when Brack did not score from third during the Reds’ failed attempt at a game-ending double play. (His run would have tied the score.) It is unclear whether this criticism was the cause, but Brack’s batting line dropped to .226-1-5 in his next 93 at-bats; the dip was brought on in part by a leg injury that sidelined him for 10 games. Worse was a season-ending 2-for-28 collapse as Grimes was forced to platoon Brack. Though the rookie outfielder – Brack spent nearly as much time in left as in center – finished with a respectable .274-5-38, he trailed only Vince DiMaggio in strikeouts in the circuit (93). The “disappointing [second-half] showing”7 caused the club to reevaluate Brack’s future in the Dodgers’ outfield. During the offseason they signed 39-year-old veteran and future Hall of Famer Kiki Cuyler as insurance against a similar collapse.

In the spring of 1938 Brack competed with six others for an outfield berth; he failed. Though he showed signs of a rejuvenated bat – maintaining a .300 average in limited play through the first few weeks of the season – Grimes had turned his back on the once-promising Brack. On May 28 he was returned to the starting lineup when left fielder Buddy Hassett was mired in a 4-for-32 slump. Brack responded with a three-hit performance to lead the Dodgers to a 6-5 win over the Braves that earned four subsequent starts. But he then went hitless in 15 at-bats and was returned to the bench. He made just 10 plate appearances over the next 40 days, and the Dodgers placed him on waivers. The last-place Phillies claimed Brack, and a trade was worked out that sent him to Philadelphia on July 11 for 26-year-old outfielder Tuck Stainback. The addition of Brack was well received in the waning days of future Hall of Famer Chuck Klein’s career: “Under the new set-up, the Phillies’ logical outfield is [Hersh] Martin, [Morrie] Arnovich and Brack, all fast-steppers. They will form the nucleus for the new outfield [team president Gerald] Nugent hopes to have,” The Sporting News wrote.8

Within a week of the trade Brack responded with three doubles in an 11-0 romp over the Pittsburgh Pirates. On July 22 he scored three runs to pace the Phillies to an 11-10 win over the Reds. After this ferocious start, Brack batted.329 from August 2 through September 22, and his season average flirted with.300. The successful rebound captured the attention of the New York Giants; the Bill Terry-led club was rebuffed in trade inquiries for Brack.

But projections of Brack as a staple in the Phillies’ outfield faded in 1939 under new manager Doc Prothro. An initial platoon with rookie LeGrant Scott and Klein evolved into time shared with Joe Marty after the latter was acquired in a four-player trade with the Chicago Cubs on May 29, 1939. (The Phillies hoped Marty would provide some power to a punchless offense.) For the first time in his major-league career Brack played something other than outfield when he was shoehorned into first base after Les Powers was sidelined with a spinal injury. Though Brack batted .315 from May 2 through September 1 (well above the team’s .261), he could not secure more than periodic use throughout the season. On September 28 Brack played in both games of a doubleheader against the Giants. They proved to be his last games in the majors. On December 4 he was sold to the St. Paul Saints in the Double-A American Association. Despite his limited play in 1939 – a career-low 270 at-bats – Brack managed a .289-6-41 line (all single-season career highs).

Over the next four years Brack bounced among six teams in the American Association, the Texas League and the International League. In 1940 his “dizzy opening pace”9 led the American Association in homers and RBIs before a second-half slump relegated him to the bench. Two years later, while playing for Oklahoma City, a Giants affiliate, Brack was the team’s biggest drawing card before his promotion to Jersey City: “[after a] sensational early streak by the powerful little left fielder … [Brack has] been tearing the cover off the ball.”10 In an ironic twist, he ended the 1943 season with the organization that initially elevated him to the majors, playing for the Dodgers’ Doiuble-A affiliate in Montreal (.309 in 194 at-bats). But there was no evidence of the Dodgers – or the other major-league organizations for which he played over the four years – giving thought to a promotion for Brack.

On April 15, 1944, Brack enlisted in the US Navy. He trained at the Sampson Naval Training Center in upstate New York before serving in the Pacific Theater during World War II. During this time Brack was able to fit in some baseball. On July 16 his home run led the Sampson squad to an 18-2 win over Cornell University. In 1945 Brack was teamed with at least 23 other professional players while stationed in Hawaii. He was selected a second-team All Star in the 14th Naval District League. On November 22, 1945, two months after World War II ended, he was discharged.

In 1946 Brack attempted to revive his career by aligning himself with his former success with the Oklahoma City Indians. The reunion proved of short duration when he was released in June. Brack resurfaced with the Greenville (Texas) Majors in the Class C East Texas League, placing among the league leaders with a .349-18-107 line. He continued to produce in the low minors in Texas and Arizona through 1948. There is some indication that the 41-year-old (though he still passed himself off as five years younger) attempted another comeback in 1949 but did not play. He retired the same year.

Brack’s decision to play in the Lone Star State during the latter years of his career was driven in part by personal choice. At some point in the late 1940s he married Texas native Ruby Pearl Watts. This was Brack’s third and longest marriage. In the early 1930s he had a short-lived union with Lida Moore while playing in the Piedmont League. Around 1935 Brack married again: to Kentucky native Hallie B. Foree. Four years later the union produced his only offspring, Roger Herman Brack. But this marriage also ended in divorce (possibly while Brack was away in the service). It appears Brack had almost no interaction with his son thereafter.

Brack and Ruby Pearl moved to Longview in northeast Texas, where he found employment with the Lone Star Steel Company. This decision proved ill-fated in 1957 when the company was embroiled in a bitter strike called by the United Steelworkers of America. “[R]are was the kind of violence that marred the Lone Star Steel strike at Daingerfield [40 miles north of Longview] … where bombings and shootings occurred and a large force of rangers and highway patrolmen was needed to restore peace.”11 It is unclear whether Brack played a direct role in the strike but he appears to have suffered the consequences: At some point in the late 1950s he was either laid off or fired.

In October 1959 Brack faced another blow when his wife was hospitalized in Greenville, Texas (northeast of Dallas), for treatment of breast cancer. Despondent over the loss of work and the potential loss of his beloved spouse, on January 20, 1960 (two months before his 52nd birthday), Brack drove to a remote location in Greenville, placed a gun to his right temple, and took his own life. His wife followed him in death 26 days later. They were buried in Memoryland Memorial Park in Greenville.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Margaret A. Brack, the player’s daughter-in-law, and SABR member Bill Mortell for their research assistance. Further thanks are extended to Len Levin for review and edit of the narrative.

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted the following:

Ancestry.com.

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/0957655a.

http://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/oes02.

http://thedeadballera.com/Obits/Obits_B/Brack.Gibby.Obit.html.

Notes

1 “Batting Marks of Two Dodgers Rise and Fall on Fans’ Attitude,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1937: 1.

2 “Betzel Likely to Stay as Colonels’ Manager,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1933: 5.

3 “Scouts Watching Young Colonel,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1935: 2.

4 Another source indicates 23 homers. In June 1936 Brack was robbed of another dinger when a line drive down the left-field line was ruled foul. A long delay ensued when Louisville manager Burleigh Grimes and his Toledo Mud Hens’ opposite, Fred Haney, engaged in an on-field fight over the call.

5 “Grimes, Twice a Dodger, but Never a Work Dodger, Using Psychology-Cure to Take Goofiness Out of Club,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1937: 5.

6 Shortly thereafter Louisville negotiated a one-year working arrangement as the Dodgers’ only Double-A affiliate.

7 “New English Lure in Dodger Bait Box,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1937: 2.

8 “New Ball to Stay, Says Phils’ Prexy,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1938: 3.

9 “New Faces Help Saints Do About-Face on Road,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1940: 1.

10 “All’s Okay at Okla. City Except for Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1942: 16.

11 Ruth A. Allen, George N. Green, and James V. Reese, “STRIKES,” in Handbook of Texas Online (tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/oes02), accessed December 20, 2015. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Full Name

Gilbert Herman Brack

Born

March 29, 1908 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

January 20, 1960 at Greenville, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.