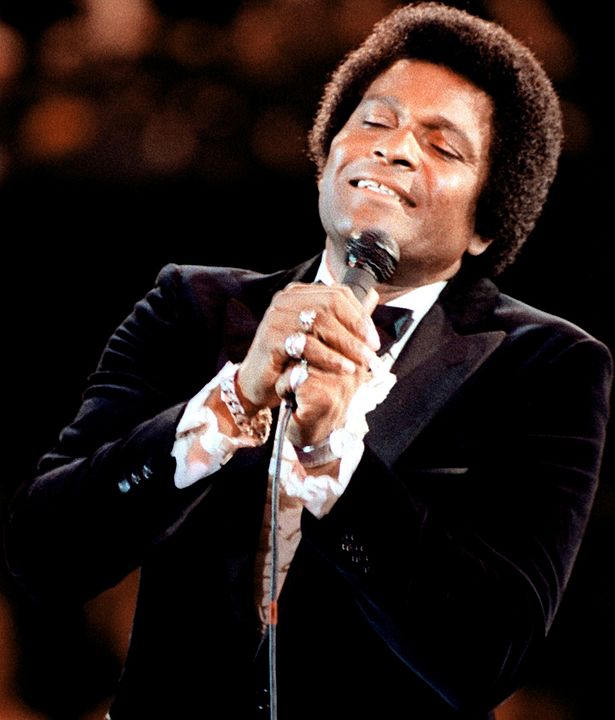

Charley Pride

Charley Pride, the son of a Mississippi sharecropper, dreamed of becoming a Hall of Famer. “Years from now,” he once said, “when they ask who hit the most home runs, I don’t want the answer to be Babe Ruth, I want it to be Charley Pride. When they ask who was the last player to hit four hundred, I don’t want the answer to be Ted Williams, I want it to be Charley Pride.”1 Baseball was Pride’s ticket out of picking cotton as a young boy in the sweltering heat. He had watched his hero, Jackie Robinson, break baseball’s color barrier and knew poor boys like him now had a chance at the major leagues. “For kids like me and my brothers, baseball was suddenly something worth working at,” he said.2

Charley Pride, the son of a Mississippi sharecropper, dreamed of becoming a Hall of Famer. “Years from now,” he once said, “when they ask who hit the most home runs, I don’t want the answer to be Babe Ruth, I want it to be Charley Pride. When they ask who was the last player to hit four hundred, I don’t want the answer to be Ted Williams, I want it to be Charley Pride.”1 Baseball was Pride’s ticket out of picking cotton as a young boy in the sweltering heat. He had watched his hero, Jackie Robinson, break baseball’s color barrier and knew poor boys like him now had a chance at the major leagues. “For kids like me and my brothers, baseball was suddenly something worth working at,” he said.2

His baseball dreams never materialized, however. The Negro Leagues were vanishing, and Pride injured his arm. Before long, Uncle Sam requested his services. Pride fought to keep his dream alive, even inviting himself to spring training with the Mets. But that career was just a dream, and Cooperstown would never become a reality.

But Charley made it to another hall of fame. He couldn’t throw a ball like a major leaguer, but he could pick and pluck a guitar and attract crowds with a smooth baritone voice. That talent led him to the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville. Through the 1980s, only Elvis Presley had sold more RCA records. With 29 No. 1 hits — 52 in the Top 10, gold records, GRAMMY and Country Music Association awards, and millions of records sold worldwide, Charley Pride is a star in the music industry. Because of the color of his skin, he was forced to overcome the Jim Crow South. While he didn’t follow Jackie Robinson on the field, he broke the color barrier in country music — despite those who claimed country music fans would never accept an African American singer.

Charl Frank Pride was born on March 18, 1934, in Sledge, Mississippi, in the Delta region, the second of 11 children born to Mack and Tessie B. (Stewart) Pride. His father was a sharecropper. His older brother, Mack Jr., played in the Negro Leagues in 1955-56. When the clerk who typed his birth certificate added “ey” to his name, his father would have none of that. “I named you Charl and that’s your name,” he bellowed.3 But his son chose to become Charley.

Mack Sr. was a strict religious disciplinarian and deacon in a Baptist church. “He was never playful with us, seldom praised us for our accomplishments, never hugged us or otherwise expressed affection,” Charley remembered. “When he decided that something would be a certain way, there was no further discussion.”4 The family lived in a small three-room house where the children slept three or four to a bed alternating head to toe. “The house was little more than a tin and cracked-wood shack and in wintertime there was no way to keep it warm throughout the night,” Pride remembered.5

The days of the segregated South had a profound effect on Charley’s life, from the lack of public colored toilets to facing racial slurs walking to school. Yet Pride remembered his mother’s words: “There’s good people here. There’s good people everywhere. You’ve got a lot you’re going to have to do and you can’t do it carrying a load of resentment with you.”6

When the evening chores were completed, Charley sat by the Philco radio, listening to the Grand Ole Opry on WSM in Nashville and singing along. “Charley, how come you want to sing white folks’ music?” his sister Bessie asked. Charley had no idea—he simply liked the music. Others had even stronger responses to him singing “white men’s music.” Pride saved enough money to order his first guitar from the Sears, Roebuck catalog when he was 14. He learned to play it by listening to the radio and from watching the country singers who came to Sledge on the weekends.7 Charley also played baseball with his brothers Mack and Ed, practicing using a henhouse for a backstop. They would sneak off on Sundays to play ball despite facing their father’s punishment for dishonoring the Sabbath.8

In the spring of 1952, the 18-year-old Charley unsuccessfully tried out for the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League. He instead joined an all-black team in the Iowa State League called the Wall Lake Popcorn Kernels.9 Players were paid from the gate receipts and went without food when games were canceled. “It rained a lot,” he remembered. “We were getting hungrier and hungrier. I pulled up weeds and chewed the roots. Certain types didn’t taste too bad.”10 Pride was cut from the Iowa team, which later disbanded.11

He returned to Memphis and won a spot on the Red Sox. Pride would sing country songs on the long bus rides. “He’d be in the back of the bus picking his guitar with two strings,” his teammate, Otha Bailey, remembered. “We’d all laugh at him, but I think he knew where he was going.”12

New York Yankees scout Dizzy Dismukes — a former star pitcher in the Negro Leagues — offered Pride $300 to sign with the Yankees’ farm team in Boise, Idaho, in 1953. “You could pick cotton all season and not make that much money,” Pride wrote.13 He joined the club for spring training in Rio Vista, California. “I had a strong pitching arm,” Pride remembered, “but a tendency to overwork it, throwing too hard before I was ready.”14 He was demoted to the Class D club in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, but wasn’t with the team long after being hammered in a loss.15 He was given a bus ticket back to Memphis, where he pitched briefly at the end of the season.16

Manager Goose Curry took Pride and Jesse Mitchell with him in 1954 when he went to manage the new Negro American League team in Louisville, Kentucky. The team was financially destitute and had no means of transportation, so Pride and Mitchell were later sold to the Birmingham Black Barons for cash so Curry could buy a team bus. “Jesse and I may have the distinction of being the only players in history to be traded for a used motor vehicle,” Pride joked.17 He was released by Birmingham, because, said club owner William “Sou” Bridgeforth, he kept everyone up at night with his singing.18

Pride joined the El Paso club in the Arizona-Texas League in 1955. He was released in April but caught on with the Nogales Yaquis of the Class C Arizona-Mexico League.19 “I was unaccustomed to Mexican and Tex-Mex food,” Pride joked, “and it seemed that the whole time I was on the border my mouth bore wounds inflicted by hot peppers.”20 Pride rejoined the Memphis Red Sox and enjoyed the best season of his career, batting .367 with 10 home runs.21 But an injured arm ended his season. “When [major league scouts] saw that arm go, I didn’t see them at the park no more.”22

Pride’s arm healed, but he started throwing a knuckleball to alleviate strain on his arm. He returned to Memphis in 1956 and made an amazing turnaround, winning 14 games and representing Memphis at the East-West Game in Chicago.23

Charley Pride, second from left, with the Memphis Red Sox in the mid-1950s. (CHARLEYPRIDE.COM)

In the offseason Pride toured the South with an All-Star team against a team organized by Willie Mays. He remembered losing a 2-1 game in Albany, Georgia, with his knuckler silencing the bats of Mays and Hank Aaron. Pride guided his team, which had lost 16 straight, to victory, closing out a 4-2 game with four scoreless relief innings. “Hank Aaron never got a hit off me during that whole tour,” Pride boasted.24

Pride also met the love of his life in the summer of 1956. Rozene Cohran worked in a restaurant down the street from Martin Stadium. “Rozene came from a background that was as alien to me as a camel in a cornfield,” Pride wrote. “She had finished high school, attended college and cosmetology school, and had an air of maturity and self-assurance. She came from a home where love and affection were openly expressed.”25 Rozene and her three sisters (Pauline, Hortense, and Irma) worked the farm and followed baseball like their father. “She was smart, beautiful, independent, and could explain the infield fly rule,” Pride wrote. “What else could a guy want?”26

That November, Pride was drafted into the Army and reported to basic training at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas. He and Rozene were married before the year ended and Charley was sent to quartermaster school in Fort Carson, Colorado. He helped the Fort Carson baseball team win the All-Army Sports Championship. Pride was discharged after 14 months. He could now spend time with his newborn son, Kraig.27

Pride had a strong 7-3 season for Memphis in 1958. He was the starting pitcher in the East-West game, shutting out the East for the first three innings.28 Refused a raise, he sat out the 1959 season, choosing to work at a lumber company.29 In 1960, he read an ad in The Sporting News: the Missoula (MT), Timberjacks of the Class C Pioneer League were looking for players.30 Missoula was the antithesis of the South. “It had the kind of free, frontier spirit that made anything seem possible and I fell in love with the state immediately,” Pride beamed. His career in Missoula was disappointingly brief, however. After just a handful of games, he was released.31

“I was 23 years old, out of money, out of prospects, and 1,700 miles from my wife and son and mortgaged furniture,” Pride wrote. “Back then they had quotas on colored players. Most teams wouldn’t have more than one or two blacks.”32 But Missoula manager Joe Tedesco helped Pride land a job at the American Smelting & Refining Company in Helena for $100 a week. Pride joined the smelter semipro baseball team: the East Helena Smelterites of the Montana State League. Rozene and Kraig soon joined Charley there, where she became a lab technician. Charley would empty coal from the railcar to the grinder during the day, go home and wash the soot from his face, then play baseball and sing at night.

Charley won his Opening Day start for the Smelterites, a complete game victory over Anaconda.33 On July 27, he went 4-for-4 in an 18-10 win, but the pregame show had more significance. The crowd was thrilled watching Pride do “a little pickin’ and singing with his guitar.”34 Their response was so overwhelming that his performing became a regular fan request.35He would often sing the national anthem and a pregame song or two, then after the game sing in the all-white bars where the team gathered. The extra cash allowed Pride to buy his own guitar and equipment.36 In early August, he was batting .420 (third in the league) and was first in hits (29).37 “Pride, who has become a favorite for his ball playing ability and singing,” The Independent-Record noted, “will answer five requests each night.”38 They finished the season with a 21-game winning streak to win the Montana State League championship. Pride batted .424.39

Pride diligently sent out newspaper clippings of his Memphis and Smelterite highlights, but major league clubs were not impressed. Then he received an invitation to a tryout from the expansion California Angels. “It was a short trial,” Pride remembered of the tryout in Palm Springs, California. “My pitching arm was sore a lot during that camp, probably from trying too hard to impress Marv Grissom, the pitching coach.”40 The Angels released him, but Pride thought it was worth a shot to appeal to the club owner, the “Singing Cowboy,” Gene Autry. Autry listened while eating a hamburger as Pride asked for another chance. Autry said he didn’t make decisions on talent. So Pride went back to Montana, where he and Rozene welcomed their second son, Dion.41 He sang and played throughout 1961 and in 1962 he batted .372.42 His 1963 season was derailed in January when a truck at the smelter ran over his foot, breaking his ankle.43

In December, Pride sang at the intermission of a show in Helena headlined by Red Sovine and Webb Pierce, but Red Foley subbed for Pierce that night. Pride sang, “Heartaches by the Number” and “Lovesick Blues.”44 Neither “Red” had ever heard such a voice. “I don’t believe it,” Sovine said. “You ought to go to Nashville. I don’t care what color you are. You should go to Nashville. Go to Cedarwood Publishing and tell them I sent you.”45 But Pride had another goal in mind: trying out for the New York Mets.

“Surely I could get a shot with the worst team in the country,” he surmised of the expansion team which had finished 51-111 the previous year.46 Pride mailed newspaper clippings from his scrapbook to George Weiss, the Mets’ general manager, announcing that he would be attending camp. He even purchased some Louisville Sluggers with his name engraved on them and shipped them to the Mets’ spring facility. He set out for Florida. “If I didn’t come back as a member of the Mets,” he said, “I could hitchhike.”

Sammy Drake, whom Pride had met at the Angels’ camp in 1961, helped get Pride to the ballpark. Players had seen the shipment of bats and wondered who the heck Charley Pride was.47 The next morning, he saw manager Casey Stengel walking down the hall. “Mr. Stengel, I’m Charley Pride and…” Pride clumsily introduced himself. “We’ll be going to the ballpark in a few minutes,” Stengel growled back. At the park, Pride overheard Stengel telling team officials. “We ain’t running no damn tryout camp down here. Take him downtown and put him on a bus to anywhere he wants to go.”48 Pride’s major league dreams were over just like that.

Flipping through his wallet, Pride found the Cedarwood card Red Sovine had given him and took a bus to Nashville. He saw Webb Pierce, who sent him to meet agent Jack D. Johnson. Johnson asked Pride to sing a few numbers, then asked Pride how long he was going to be in Nashville. “I’m on vacation,” Charley replied. “Since I’m here I intend to meet everybody in Nashville that I can.” “Fella,” Johnson replied, “you’ve met everybody here you need to meet. I’m going to be your manager. You go on home and I’ll send a contract for you to sign. I’ll start trying to find you a record label.”49 But Johnson struggled trying to convince record companies that America was ready for a black country singer. Executives liked the music until they were shown Pride’s picture. Meanwhile, Pride was back in Missoula performing in a band called the Nighthawks and playing one last season for the Smelterites.50

Johnson eventually found a receptive producer in Jack Clement, who brought Pride to RCA to record seven songs he had written. When the songs were marketed to local radio stations, neither a biography nor a picture of Pride was included for fear of racial backlash. “I knew that many of them wouldn’t accept me if they realized I was black,” Pride said. “When the record company decided to hide my color, I thought it was a good idea.”51 RCA Executive Chet Atkins signed Pride to a contract in late 1965. By then, Charley and Rozene had welcomed their only daughter, Angela.

Pride’s first single, “The Snakes Crawl at Night,” was an immediate Top 10 country hit, followed by “Just Before I Met You,” in 1966 and “Just Between You and Me,” in 1967.52 His first album, Country Charley Pride, hit gold and many fans came to realize for the first time that Charley was black.53 The audience still didn’t know at a show in Detroit until he came out on stage to uncomfortable silence. “Ladies and gentlemen,” Pride said, “I realize it’s kind of unique, me coming out here on a country music show wearing this permanent tan.”54 In 1967, Pride toured the South with Willie Nelson, which helped break down more racial awkwardness.

Pride’s 1971 song, “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin’,” is still his most recognizable work. He released three albums in 1969 and the first, Charley Pride In Person, went gold. A hectic schedule made it difficult to keep living in Montana, so the Prides moved to North Dallas, Texas. In 1971 he received the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award; he was the CMA’s top male vocalist for 1971 and ’72. Pride won two GRAMMY awards in 1971: “Did You Think to Pray” won the Best Sacred Performance, and “Let Me Live” won the Best Gospel Performance (other than Soul). In 1972, he took home another GRAMMY when Charley Pride Sings Heart Songs won the Best Country Vocal Performance, Male.

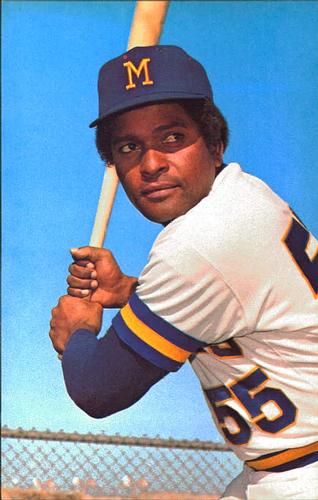

When the new Texas Rangers franchise began in 1972, Pride became a regular guest. The Rangers helped Pride fulfill one of his lifetime dreams: batting in the major leagues. Granted, it was just a spring training game in 1974, but Pride (then nearly 40) still showed some of his athletic abilities by singling and grounding out against the legendary Jim Palmer.55

When the new Texas Rangers franchise began in 1972, Pride became a regular guest. The Rangers helped Pride fulfill one of his lifetime dreams: batting in the major leagues. Granted, it was just a spring training game in 1974, but Pride (then nearly 40) still showed some of his athletic abilities by singling and grounding out against the legendary Jim Palmer.55

Pride struggled with manic depression and fought bouts of paranoia and delusions, which convinced him to enter a psych ward in Dallas in 1989. He slowly recovered and remembered those dark times in his autobiography, Pride: The Charley Pride Story, which he wrote with Jim Henderson in 1994. “Manic depression can be a nightmare,” he wrote. “I was probably hesitant to accept the fact that I was afflicted by it because it smacked of mental disease or emotional disorder or something just as horrible. It is neither of those. It is a medical condition like diabetes or any other malady over which the mind has no control. My advice,” he continued, “get help. It is treatable and controllable.”56

Pride became involved in real estate, banking, and Chardon, his own booking and management company. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000. Monetary success also enabled Pride to fulfill a small part of the fantasy of his youth. In 2010 he invested $2.5 million and became a part-owner of the Texas Rangers.57

He didn’t follow Jackie Robinson on the ballfield, but the Negro League Baseball Museum presented Pride with the Jackie Robinson Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013. “The award is given for career excellence in the face of adversity,” said Bob Kendrick, museum president. “You look at what he did — he’s a really good baseball player. And then he fell back into a country music career. We should all have a fallback plan like that.”58

Charley and Rozene have surpassed 60 years of marriage and still lived in North Dallas as of 2020. In 2017 he received the GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement award, and in 2020 Country Music’s Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement honors. A 2019 episode of Public Television’s American Masters series entitled “Charley Pride: I’m Just Me,” told the story of his life, from a Mississippi cotton field to Memphis, Montana, Mexico, and all over the world,

Pride died at the age of 86 on December 12, 2020.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author wishes to thank Cassidy Lent of the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York, for providing a copy of Charley Pride’s Hall of Fame file.

Photo credits: Charley Pride performs at the Capital Centre on President Reagan’s Inauguration Day, January 20, 1981 — US Department of Defense photo. Charley Pride poses with a baseball bat during spring training with the Milwaukee Brewers in 1973 — Trading Card Database.

The author also benefited from the following:

Baseball-Reference.com

Bob Lemke, “Charley Pride’s Boise career detailed,” in Bob Lemke’s Blog, May 13, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2019. https://boblemke.blogspot.com/2012/05/charley-prides-game-boise-career.html

“Charley Pride.” Grammy Awards. Retrieved December 17, 2019. https://grammy.com/grammys/artists/charley-pride

“Charley Pride: Chart History.” Billboard. Retrieved December 15, 2019. https://billboard.com/music/charley-pride/chart-history/HSI/2

Greg Gosselin, “Biography,” Charley Pride website. Retrieved December 15, 2019. https://charleypride.com/about

Jason Ratliffe, “Baseball Set Stage for Country Legend Pride,” MILB.com. February 23, 2006. Retrieved December 21, 2019. https://milb.com/milb/news/minor-league-baseball-set-stage-for-country-music-legend-charley-pride/c-310870752

Nadira Hira, “Country Music Star Charley Pride Shines Brighter Than Ever After Decades in the Business.” Newsweek, November 1, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019. https://newsweek.com/charley-pride-country-music-interview-1469059

William J. Plott, Black Baseball’s Last Team Standing: The Birmingham Black Barons. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019).

Notes

1 Charley Pride and Jim Henderson, Pride: The Charley Pride Story. (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1994), 65. (Hereafter referred to as Autobiography).

2 Autobiography, 58.

3 Autobiography, 23.

4 Autobiography, 33-34.

5 Autobiography, 24.

6 Autobiography, 46, 50.

7 “Country Singer Charley Pride Talks About His Career.” Weekly Edition: The Best of NPR News [NPR] (USA), 15:00 ed., 14 Oct. 2000. NewsBank: America’s News. Accessed 15 Dec. 2019.

8 Autobiography, 59-60.

9 “Merchants Meet Wall Lake Here Sunday Night,” Carroll Daily Times, June 7, 1952: 2.

10 Bill Plott, “From Pitching to Picking: Ex-Black Baron Charley Pride Comes Back for Rickwood Classic,” Birmingham News, May 9, 1999: 17-A.

11 “Wall Lake Quits Loop,” Des Moines Register, July 8, 1952: 14.

12 Autobiography, 60-62; Bob Carlton, “For the Love of the Game: Former Negro Leagues Players Say They Just Wanted a Chance to Play,” Birmingham News, February 5, 1995: 1E.

13 Autobiography, 67.

14 Autobiography, 67; “Yankees Take Bees in Ninth Frame,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 1, 1953: 14.

15 Associated Press, “Green Bay Wins 21-5 to Take League Lead; Gets 14 runs in Fifth Inning,” Wausau Daily Herald, May 15, 1953: 12; “Boise Options Pride,” The Semi-Weekly Sportsman-Review, May 10, 1953: 32.

16 Autobiography, 68; Ken Dulo, “Auscos Show No Respect for Memphis Club,” Herald Press (St. Joseph, Michigan), August 5, 1953: 12.

17 Autobiography, 69.

18 “William ‘Sou’ Bridgeforth. Limestown County Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 21, 2019. https://lcshof.com/view.php?id=36

19 “Texans to Meet Indios,” El Paso Times, April 13, 1955: 27.

20 Autobiography, 70.

21 Autobiography, 72. This is by his recollection and not any definite statistics.

22 Sam McDowell, “Negro Leagues Museum Honors Singer and Ex-Ballplayer Charley Pride,” Kansas City Star, April 10, 2013.

23 Autobiography, 75.

24 Autobiography, 84-86; Associated Press, “Charley’s Pride: Country Singer Loves Baseball,” unknown article in Pride’s Hall of Fame file.

25 Autobiography, 79.

26 Autobiography, 81.

27 Autobiography, 87-89; 96-97.

28 Lee D. Jenkins, “East Defeats West, 4-3,” Chicago Defender, August 25, 1958; “Memphis Ready With New Faces,” Chicago Defender, May 23, 1959.

29 Plott; Autobiography, 101.

30 Autobiography, 102.

31 “Boise Braves Defeat Timberjacks Twice,” The Missoulian, May 2, 1960: 8; “Jacks Open Series Against Great Falls Here Tonight,” The Missoulian, May 10, 1960: 9.

32 Plott.

33 Dave Carlson, “Smelterites Win Opener 4-3 in Eight Innings,” The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana), June 11, 1960: 8.

34 “Special Entertainment Program Will Precede Ball Game,” The Independent-Record, July 27, 1960: 11.

35 “Singin’ Charlie [sic] Pride to Appear at Game in East Helena Monday,” The Independent-Record, July 31, 1960: 10.

36 Autobiography, 109-112.

37 “State League Leaders,” The Independent Record, August 7, 1960: 12.

38 “Charlie [sic] Pride to Sing at East Helena Games Tonight, Friday,” The Independent Record, August 10, 1960: 9.

39 Dave Carlson, “East Helena Smelterites Win State League Crown,” Independent-Record, September 2, 1960: 10. “Final State League Records,” Independent-Record, September 18, 1960: 7.

40 Autobiography, 114; Larry Whiteside, “Singer Snubs $100,000 to Join Brewer Drills, The Sporting News, March 13, 1971.

41 Autobiography, 114-116.

42 Independent-Record, May 19, 1961: 9; Ibid, several issues in July of 1961; Mayo Ashley, “Smelterites Smash McQueens, 26-4,” Independent-Record, July 27, 1962: 11; Mayo Ashley, “Butte Mace Master Paces Final 1962 Copper League Statistics,” Independent-Record, August 26, 1962: 8.

43 “Charley Pride is Injured in Smelter Mishap,” The Independent-Record, January 30, 1963: 10.

44 The show was advertised in the Independent-Record between December 5-12, 1963. Some accounts, including Pride’s own autobiography, place or infer that this show and the smelter truck incident both happened in 1962. Newspaper articles in Montana clearly reveal the truck accident occurred in January 1963 and this show happened (with Pierce being replaced by Sovine) in December of 1963. The tryout with the Mets, which some sources list happening in 1962 or 1963, had to have happened in 1964, since Pride would not have recovered that quickly and the tryout had to happen after the show since he then remembered the contact for Nashville.

45 Autobiography, 119.

46 Autobiography, 124.

47 Autobiography, 125.

48 Autobiography, 128-129.

49 Autobiography, 136.

50 “Charley Pride in Helena: Hits on the Baseball Diamond—and the Country Music Charts,” Helena As She Was. Retrieved December 17, 2019. https://helenahistory.org/Charlie_Pride_In_Helena.htm

51 Lardine, 6.

52 Autobiography, 139-148.

53 “Charley Pride,” Country Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 14, 2019. https://countrymusichalloffame.org/artist/charley-pride/

54 Hira.

55 Associated Press, “Pride’s Dream Blasting Balls, His Business Belting Ballads,” from an unknown article in Pride’s Hall of Fame file marked 5/23/71; Another unknown clipping in Pride’s Hall of Fame file marked 3/24/74.

56 Autobiography, 193; Jack Dickey, “How Charley Pride Went From Negro League Ballplayer to Country Music’s Jackie Robinson,” Sports Illustrated, March 21, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2019. https://si.com/mlb/2018/03/21/charley-pride-texas-rangers-country-music

57 Country Music Hall of Fame; Evan Grant, “Charley Pride: Pride of the Rangers,” Dallas Morning News, March 11, 2010: C3.

58 McDowell.

Full Name

Charl Frank Pride

Born

March 18, 1934 at Sledge, MS (USA)

Died

December 12, 2020 at Dallas, TX (USA)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.