Gene Autry

Gene Autry was the kind of man who paid the bills for old friends in their old age, rode in the front seat beside his chauffeur, and showed up in the bar of his resort hotel to lead guests in a sing-along. During his heyday as a singing cowboy, his fans ranged from the obvious — Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson — to the improbable — Franklin D. Roosevelt and Ringo Starr. Thirty years after he quit performing, his theme song, “Back in the Saddle Again,” returned to the pop charts on the movie soundtrack for Sleepless in Seattle.

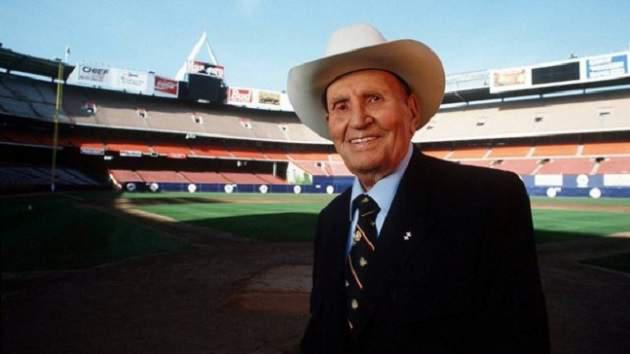

He once described himself as “a frustrated ballplayer,” and delighted in his second career as a baseball owner.1 The Angels were his passion for the last four decades of his life. A portly, perpetually smiling man decked out in a western suit and a big Stetson — white, of course — Autry often traveled with his team and spent lavishly on free agents in futile pursuit of a championship. The Angels retired number 26 in honor of their 26th man.

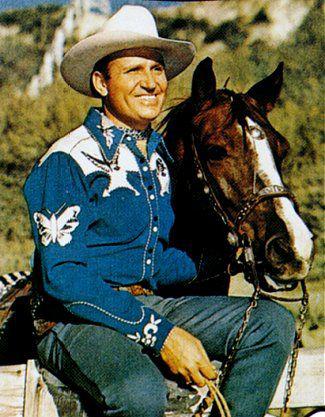

Autry never was a cowboy, but he played one on TV and radio and in movies. “I was the first of the singing cowboys,” he said. “I’m not sure I was the best. But when you’re first it doesn’t matter. No one can ever be first again.”2

He introduced two of the most popular Christmas songs, and invested his Hollywood earnings to build a fortune that landed him on Forbes magazine’s list of the 400 richest Americans for 10 years. His television sidekick, Pat Buttram, said, “Gene Autry used to ride off into the sunset. Now he owns it.”3

Orvon Grover Autry was born in Tioga, Texas, on September 29, 1907, the first child of Delbert Autry and the former Elnora Ozment. He seldom spoke of his childhood because he wanted to forget most of it. His father was generally worthless, absent more often than present, and his mother and her four children had to depend on the charity of relatives in Texas and Oklahoma. Orvon dropped out of high school to help support the family as a railroad telegrapher.4

When he was 12, he had saved $8 from farm chores to buy a guitar out of the Sears Roebuck catalog. He liked to tell of the night that the world’s most famous Oklahoma native, Will Rogers, walked into a railroad depot, heard him picking and singing, and encouraged his dream of a music career. The tale may be a press agent’s invention; its first documented appearance didn’t come until after Rogers’ death.

At 20, Orvon traveled to New York in search of a recording contract, but was turned away. He came home with a new name, Gene Autry, probably borrowed from a popular crooner, Gene Austin, whom he met on the trip.

In his first radio gig, at KVOO in Tulsa, he was billed as Oklahoma’s Yodeling Cowboy and imitated country star Jimmie Rodgers. His first hit record, “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine,” propelled him to the big time on Chicago’s WLS Barn Dance, the model for Nashville’s enduring Grand Ole Opry.

During a trip home to Oklahoma, Autry met Ina Mae Spivey and married her four months later, on April 1, 1932. The wedding was so sudden that some friends thought it was an April Fool’s prank, but the marriage lasted 48 years. After Gene’s mother died that spring, his two sisters and brother moved in with the newlyweds. Ina, just 21, became their surrogate mother. The Autrys never had children.

On July 4, 1934, he, Ina, and his comic sidekick, Smiley Burnette, left Chicago for Hollywood in Gene’s Buick. He thought movies would help sell his records. His debut was a singing cameo in In Old Santa Fe, starring a leading cowboy actor, Ken Maynard. The greenhorn appeared stiff and awkward on screen. Embarrassed, he decided to go back to radio. But Maynard was supportive and gave him a small part in a serial, Mystery Mountain. Autry was more singer than cowboy; a stunt man had to step in when he couldn’t handle a galloping horse.

Autry’s big break came when Maynard was fired for his drunken tantrums. The newcomer took over the lead role in a bizarre 12-part serial, The Phantom Empire, where he played a singing cowboy battling robots and mad scientists. (Years later, when Maynard was living in a trailer park, Autry sent him monthly checks. He made donations to several other early benefactors who were needy in their declining years.)

Three years after Autry arrived in Hollywood, a trade publication named him the #1 star of action melodramas in 1937. His movies for Republic Pictures followed a simple formula for wholesome, if bland, family entertainment: Good guy defeats bad guy, but never shoots first and never kills anybody. Hero gets girl, but never kisses her. Kissing was allowed in the early films, but the clinches disappeared when the studio realized that Autry’s core audience was pre-teen boys, who didn’t go for that mushy stuff. They preferred to see him with his horse, Champion.

While Autry made action movies, they were unconventional westerns. Before signing him to his first contract, a studio executive had complained that he lacked “virility.”5 At 5-feet-9, he was not tall, muscular, or imposing. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther described him as a “medium-height, sandy-haired, pink-cheeked, blue-eyed, baby-faced fellow.”6 Nor was he an acrobatic horseman like Maynard and the king of silent-screen cowboys, Tom Mix. Songs took on a larger role in Autry films than gunplay or fistfights.

By 1937 he was making $6,000 per picture, equivalent to around $100,000 in 2017, but was still ridiculously underpaid given his popularity.7 He went on strike.

During his holdout, Republic brass created a replacement singing “cowboy” they named Roy Rogers. Born Leonard Slye in Cincinnati, he had had bit parts in several Autry films.8 The two became rivals, but friendly ones.

From his earliest days, Autry used every avenue to turn his fame into money. The Sears catalog sold Gene Autry Roundup guitars, and he was said to be the first Hollywood star to put his name on comic books, school lunchboxes, jeans, and more than 100 other products, though he refused to endorse cigarettes.9 With records, songbooks, and personal appearances, his outside income exceeded his film earnings.

Autry took his stage show to England and Ireland in 1939. It was a triumph; his biographer, Holly George-Warren, likened it to the Beatles’ first American tour.10 A reported 250,000 people jammed the streets of Dublin for a look at the cowboy. In the crowd was another American tourist, P.K. Wrigley, the owner of the chewing-gum company. When Wrigley returned home, he ordered his ad agency to sign Autry for a weekly CBS radio show sponsored by Doublemint gum. That added a new profit center to Autry’s empire, giving him a foothold in all entertainment media.

His career reached its pinnacle when theater owners voted him the #4 male box-office attraction of 1940, behind Mickey Rooney, Clark Gable, and Spencer Tracy. It was a stunning achievement for a B-movie actor whose greatest appeal was in small towns rather than big-city film palaces. His income in 1941 approached half a million dollars.

Autry’s reign as the #1 western star ended while he was serving in the Army Air Corps during World War II. When he sued Republic trying to get out of his contract, the studio retaliated by promoting Roy Rogers, who was found unfit for military service because of a bad back. In 1943 Rogers climbed to #1, a pedestal Autry never regained. Life magazine headlined a cover story on Rogers, “King of the Cowboys.”11

Seeing harsh evidence that stardom was temporary, Autry turned his energy toward business after the war. He bought radio and television stations and hotels, and invested in oil wells and real estate. When the California Supreme Court finally freed him from his Republic contract, he formed his own production company to make movies in partnership with Columbia, one of the major studios. The arrangement gave him control of his work as well as a tax shelter.

He also resumed his radio show and personal appearance tours, and enjoyed six top-10 records in 1947. In the fall he released “Here Comes Santa Claus,” a song he co-wrote after he heard a child’s exuberant shout at a Christmas parade.12 It became a holiday standard, but nothing compared to his next Christmas song.

“Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” carried Autry to the top of Billboard’s country and pop charts for the first time and sold two million copies in 1949, with millions more to follow. It is often said to be the second best-selling Christmas record in history, after Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas,” but the Guinness Book of World Records lists it in third place behind another Crosby hit, “Silent Night.”

In 1950 Autry was the first major movie star to jump into television. William Boyd, whom he dismissed as a third-rate actor, had become a TV cowboy sensation by recycling cut-down versions of his old Hopalong Cassidy movies, igniting a children’s craze for “Hoppy” merchandise.

In 1950 Autry was the first major movie star to jump into television. William Boyd, whom he dismissed as a third-rate actor, had become a TV cowboy sensation by recycling cut-down versions of his old Hopalong Cassidy movies, igniting a children’s craze for “Hoppy” merchandise.

Autry began starring in weekly original half-hour films on CBS-TV. His company produced three more western series for the network. One was Annie Oakley, the first TV western with a female star, his sometime girlfriend Gail Davis.

But Autry’s career was sliding downhill, and so was he. His new records weren’t selling. Television killed many of the small-town theaters that had showcased his movies. So-called adult westerns, such as High Noon and TV’s Gunsmoke, made the singing cowboys seem campy. He released his last feature film in 1953.

His heavy drinking, which began during the war, was interfering with his work. After he missed a number of shows, his longtime sponsor, Wrigley, canceled his radio and TV series in 1956. His live performances became unreliable. Although his loyal staff tried to cover for him, fans saw him fall off his horse and appear too drunk to mount up.

As Autry’s entertainment career fizzled out, his business portfolio continued to expand. One of his biggest money-makers was Los Angeles radio station KMPC. The station aired Dodgers games after the team moved west in 1958, but its signal was too weak to reach club owner Walter O’Malley’s home at Lake Arrowhead. O’Malley moved the broadcasts to a more powerful outlet, one he could hear.

KMPC, billed as Southern California’s sports station, needed a new anchor for its summer schedule. Autry thought he had found one when Hank Greenberg came calling in November 1960. The home run slugger turned baseball executive had secretly won the American League’s blessing to put an expansion team in Los Angeles in 1961. Autry was negotiating for broadcast rights when Greenberg’s plans blew up.

O’Malley didn’t want to share the LA market. He leaned on Commissioner Ford Frick, and the commissioner decreed that O’Malley deserved compensation for allowing a competing team into “his” territory. Hearing that, Greenberg walked away, throwing the AL expansion blueprint into “frightful chaos,” as the writer Frank Finch put it.13 With a franchise already awarded to Washington, the league had to have a tenth club to balance the schedule, and time was slipping away.

The familiar story is that Autry went to the AL meeting hoping to secure radio rights for the new franchise, and wound up owning the team. In fact, published reports identified him as a bidder for the team before the meeting, and he said he became interested as soon as Greenberg dropped out: “I thought it was all Greenberg. When it appeared it wasn’t, the thought occurred to me that I’d like that franchise.”14 When he went to the league meeting, Autry brought along his choice for general manager: Fred Haney, an LA resident who had managed the Milwaukee Braves to two pennants.

AL owners were facing ridicule over their bungled expansion when they met in St. Louis on December 5. Just as in the movies, the hero in the white hat came riding to the rescue. The league welcomed him as a savior, and why not? He was a famous, popular — and rich — man who wanted to own a ball club.

But O’Malley exacted a stiff price. The new team would have to pay him $350,000 for a ticket of admission to enter Los Angeles. Instead of sharing the 90,000-seat LA Coliseum with the Dodgers, the American League club would play its first season in the city’s minor-league ballpark, Wrigley Field, with room for about 22,000. That ensured that the team would lose money. Beginning in 1962, it would be O’Malley’s tenant in his new park, under construction at Chavez Ravine, paying a minimum $200,000 in rent, or 7.5 percent of gate receipts. O’Malley would keep all parking revenue and some of the take from concessions.

In addition, O’Malley didn’t want competition from television. He televised only 11 Dodger games — those in San Francisco against the archrival Giants — and the new club was limited to the same number.

All told, Autry estimated the deal was worth $750,000 a year to the Dodgers. After a meeting with O’Malley that lasted nearly all night, he agreed to pay. It was the price of doing business.15

“For me, it’s the realization of a lifetime dream,” Autry said.16 He had played semipro ball in his youth and claimed to have been invited to a Cardinals tryout camp. While filming his movies, he had organized pickup games during breaks, and had once owned a share of the Pacific Coast League’s Hollywood Stars.

The new team adopted the name of LA’s other PCL entry, the Angels. Casey Stengel, recently fired by the Yankees, turned down an offer to be the manager. Haney talked to Leo Durocher, but Durocher’s price was apparently too high. The club hired Bill Rigney, who had succeeded Durocher as manager of the Giants.

Because of the delay in awarding the franchise, Haney had only a week to prepare for the player draft that would stock the Angels’ roster. Stengel gave him a rundown on the available players, who were mostly benchwarmers and over-age veterans. AL teams were permitted to keep their front-line talent and top prospects.

Haney went for well-known names in the draft, hoping to convince LA fans that the castoffs were a real big league team. But Ted Kluszewski, Eddie Yost, Ned Garver, and Bob Cerv had to look backward to see their 34th birthdays. Haney did grab a pair of young minor leaguers who became franchise cornerstones, shortstop Jim Fregosi and catcher Buck Rodgers. After the draft he acquired pitching prospect Dean Chance.

During spring training Autry put the players up at his hotel in Palm Springs, California, and mounted a bicycle to lead them in a parade to the ballpark. The Angels opened their inaugural season with eight games on the road. They lost seven of them. The home opener produced defeat number 8 before an embarrassing turnout of just 11,931. The club rallied to a 70-91 record, still the most victories by a first-year expansion team, finishing eighth in the standings but ninth in attendance, drawing barely 600,000.

In their second season, the Angels startled the league by charging into the pennant race. They held first place on the Fourth of July and finished third, with 86 victories. Attendance nearly doubled in their first year in O’Malley’s new ballpark. Its formal name was Dodger Stadium, but the Angels called it Chavez Ravine.

Autry soon began looking for a way to climb out of the ravine. He vented his complaints in uncharacteristically blunt language: “Chavez Ravine is an expensive stadium to operate, Walter O’Malley is a difficult landlord, the Angels are treated as a stepchild by the Dodgers, … we are playing in the shadow of the Dodgers and we must build our own fan following elsewhere.”17 On August 31, 1964, he broke ground for a new stadium in Anaheim, 30 miles south, to be paid for by the city.

Renamed the California Angels, the team moved into its new home in 1966. But attendance continued to lag far behind the Dodgers, who were setting records and piling up giant profits. The Angels were Southern California’s stepchild team. They settled into mediocrity, usually in the bottom half of the standings.

Autry yearned for a championship, but he was a hands-off owner. “I’ve tried hard not to interfere with the men on the firing line,” he said. “I have wondered often why a manager did this or that, but I have tried to restrain my second-guessing.”18 Some critics thought that was why the Angels didn’t win: The owner didn’t demand it. “Gene is a fan,” a former general manager, Dick Walsh, said. “The team is a plaything, a fun thing.”19

Instead of getting tough during losing seasons, Autry treated players and managers as friends. “He knew every player and knew everything about his players … their kids’ names, their wives’ names,” pitcher Clyde Wright said. Autry went along on many road trips and made the rounds in the clubhouse before home games asking, “Anything you need?”20

Fireballer Nolan Ryan was one of the team’s few stars in the 1970s. He set the single-season strikeout record and pitched four of his seven no-hitters for the Angels. Ryan was as big a Gene Autry fan as any 9-year-old boy: “I can honestly say he is among the greatest men I have ever had the pleasure to know.”21

When free agency arrived after the 1976 season, Autry saw a chance to lift his club out of mediocrity. All it took was money, and he and his minority partner, Signal Companies, had plenty. The Angels signed three of the top-ranked free agents — outfielders Joe Rudi and Don Baylor and second baseman Bobby Grich — to long-term contracts totaling $5.25 million, equivalent to $22 million in 2017.

That doesn’t sound like much in the context of 21st century salaries, but in 1976 it was an unprecedented splurge that outraged many of Autry’s fellow owners. “I still don’t think all this is good for baseball,” he said. “But this is the way it is now, and there are certain facts of life we’re going to have to live with.”22

While he was counting on the pricey players to win games, Autry was also counting on an axiom of the entertainment business: Stars sell tickets. Attendance more than doubled in the next three years. After adding seven-time batting champion Rod Carew to their collection of free agents, the Angels won their first American League West title in 1979, then won again in 1982 and 1986. Each time they lost the league championship series.

Ina Autry died of cancer in 1980. Although they were outwardly devoted, her husband had spent large chunks of their 48-year marriage on the road or on location for his films, and had affairs with several of his leading ladies and uncounted groupies. Friends said Ina shut her eyes to all that. Most important, she had nurtured him through periods of uncontrolled drinking and unsuccessful attempts to quit.

Autry’s family life was always a pain. He supported his ex-convict father and his father’s second family for decades. His brother, Dudley, was an unfortunate chip off the old block, a wastrel and an alcoholic who tried and failed to ride the family name to a singing career and often ended up on Gene’s payroll. Dudley’s ex-wife, a trick-rope artist, also exploited the Autry name to help her career.

Eighteen months after Ina’s death, the 73-year-old Autry married Jacqueline Ellam, who was 34 years younger. A former bank executive, Jackie took over management of his businesses as he aged.

In his last years, Autry became a leading philanthropist in Southern California. He spent about $100 million to establish the Autry Museum of the American West, now known as the Autry National Center. (He had lost his first collection of western artifacts in a house fire in 1941.) He gave $5 million to build a wing of the Eisenhower Medical Center in Palm Springs, where he and Jackie had a home.

Autry spent more years of his life as a baseball owner than as a singing cowboy, but the World Series eluded him. “For sure, baseball has been the most exciting and frustrating experience of my life,” he said. “In the movies, I never lost a fight. In baseball I hardly ever won one.”23

He turned over control of the Angels to his wife in 1990. In May 1995 Autry announced an agreement in principle to sell operating control of the team to the Walt Disney Company. Soon afterward the Angels climbed into first place and adopted the rallying cry “Win one for the cowboy,” but they blew an 11-game lead and lost the Western Division title to Seattle in a one-game playoff.

The Disney deal closed in early 1996, ending Autry’s active involvement. The company acquired 25 percent of the franchise with an option to buy the rest after his death. Autry continued to attend Angels games when he was able. He contracted lymphoma and died at 91 on October 2, 1998. He was mourned as a good man, an American success story, and, for many, a reminder of happy childhood.

Autry called himself a personality, not a singer or actor. “When I started, they said I couldn’t act,” he once recalled. “Other people said I couldn’t sing, but I sure as hell could count.”24

Four years after Autry’s death, the Angels won the 2002 pennant and defeated the Giants in the World Series to claim their first championship. In the joyful clubhouse after Game Seven, manager Mike Scioscia hoisted a bottle of champagne to toast the cowboy.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors” (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Notes

1 Myrna Oliver, “Gene Autry Dies,” Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1998: 24.

2 Al Martinez, “2 Old-Time Cowboy Stars Reflect a Heroic Age,” Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1977: II-6.

3 Bruce Fessier, “Autry was sunshine in lots of lives,” Desert Sun (Palm Springs, California), October 3, 1998: 3.

4 If not otherwise credited, information about Autry’s personal life and Hollywood career comes from Holly George-Warren, Public Cowboy no. 1: The Life and Times of Gene Autry (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

5 George-Warren, 138.

6 Bosley Crowther, “A Cowboy Without a Lament,” New York Times, August 6, 1939: X3.

7 Inflation calculator at https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

8 The apartment building where Slye was born stood on the future site of Riverfront Stadium, home of the Big Red Machine. He liked to say he was born on second base. Laurence Zewisohn, “Happy Trails: The Life of Roy Rogers,” http://www.royrogers.com/roy_rogers_bio.html, accessed May 19, 2017.

9 Some Gene Autry cowboy suits were made of flammable fabric. Two children died from fires and others were hurt. Autry was the target of several lawsuits over the product.

10 George-Warren, 182.

11 Life, July 12, 1943.

12 Autry is credited as co-writer on more than 300 songs, but many of those are “star credits.” Singing stars often took writing credit on songs they popularized, and some songwriters didn’t mind because the famous name made the song more salable.

13 Frank Finch, “Rumors have AL expanding,” Los Angeles Times, December 4, 1960: H5.

14 Jeanne Hoffman, “Autry Set to Build Angels in 120 Days,” Los Angeles Times, December 13, 1960: IV-5. The first mention of Autry as one of the bidders was before the AL meetings of November 22 and December 5: Paul Zimmerman, “Greenberg Out, L.A. Team Up for Bids” Los Angeles Times, November 18, 1960: II-1.

15 Finch, “It’s Official! Angels to Play in 1961,” Los Angeles Times, December 8, 1960: IV-1; Andy McCue, Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers, & Baseball’s Westward Expansion (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 292-293.

16 Hoffman.

17 Al Carr, “When and Will Angels Move?” Los Angeles Times, February 9, 1964: 14

18 Ross Newhan, “No. 26 on the Wall, No. 1 in their Hearts,” Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1998: C6.

19 Ron Rapaport, “Angels Haven’t Had a Sweet 16,” Los Angeles Times, October 12, 1976: III-1.

20 Tom Singer, “Tribute precedes Autry’s induction to Hall,” mlb.com, July 19, 2011, http://m.mlb.com/news/article/21960212/, accessed May 22, 2017.

21 Ibid.

22 Dick Miller, “Rudi, Baylor Give Angels Case of Flag Fever,” The Sporting News, December 4, 1976: 65.

23 Oliver.

24 Richard Simon and Susan King, “Friends and fans recall an American icon,” Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1998: 25.

Full Name

Autry

Born

September 29, 1907 at Tioga, TX (US)

Died

October 2, 1998 at Studio City, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.