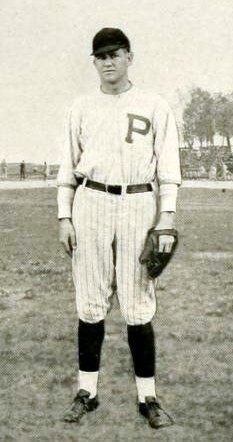

Charlie Wilson

Charlie Wilson, a shortstop in the 1930s for parts of four seasons with the Boston Braves and St. Louis Cardinals, had a modest career but may be part of cinematic history. An alleged prank by Wilson – flooding the baseball diamond because he didn’t want to practice – is said to have been one of the inspirations for a scene in the movie Bull Durham when Kevin Costner and his teammates flooded the infield with hoses. Similar pranks have been discovered going as far back as 1883, and where and when Wilson did it can’t be determined, but the fact that one of his nicknames was Swamp Baby lends some credence to the legend. If it did happen, it may have been while Wilson was a student at Presbyterian College in Clinton, South Carolina; still, the first mention of the Swamp Baby nickname that can be found was not while he was a student, but while he was playing for the Rochester Red Wings. The Rochester Evening Journal described him as Charlie Wilson, “affectionately known locally as the Swamp Baby.” So it may have happened after he turned pro.

Charlie Wilson, a shortstop in the 1930s for parts of four seasons with the Boston Braves and St. Louis Cardinals, had a modest career but may be part of cinematic history. An alleged prank by Wilson – flooding the baseball diamond because he didn’t want to practice – is said to have been one of the inspirations for a scene in the movie Bull Durham when Kevin Costner and his teammates flooded the infield with hoses. Similar pranks have been discovered going as far back as 1883, and where and when Wilson did it can’t be determined, but the fact that one of his nicknames was Swamp Baby lends some credence to the legend. If it did happen, it may have been while Wilson was a student at Presbyterian College in Clinton, South Carolina; still, the first mention of the Swamp Baby nickname that can be found was not while he was a student, but while he was playing for the Rochester Red Wings. The Rochester Evening Journal described him as Charlie Wilson, “affectionately known locally as the Swamp Baby.” So it may have happened after he turned pro.

Charles Woodrow Wilson was the son of Joseph Calvin and Laura Catherine Wilson, who were natives of North Carolina and living in Rutherfordton in 1900. By 1905, like many North Carolina mountain people, they had moved to upstate South Carolina in search of better-paying work in the textile mills. Charlie was born in Clinton, South Carolina, on January 13, 1905. His father died in 1908, and in 1910 his widowed mother was living in Hunter Township with her children: Ola, 16; Sidney, 14; George, 12; Furman, 10; Charlie, 5; and Rosa, 2. Both Laura and Sidney were working as spinners in a textile mill.

Laura Wilson died in 1911, and George, Furman, and Charlie were sent to live at Thornwell Orphanage in Clinton. Furman died while they were living at the orphanage. Thornwell, which was founded in 1875, provided a good education for its pupils, as well as teaching them such trades as printing and farming. According to a history of the orphanage, “Charles was always full of fun and took life and work with a smile. He tackled work on the farm, then took a little experience working in the printing office. But his ‘hobby’ was athletics.”[1] Charlie starred on the orphanage’s football team, which won the state championship in 1923. During two of his years at Thornwell, he also played on local textile-mill teams, appearing for Clinton in 1920 and Laurens in 1922.

After graduating from Thornwell, Charlie spent four years at Presbyterian College in Clinton, where he was a true athletic standout. He was the captain of the freshman basketball, football, and track teams, and played varsity basketball, track, and baseball. After his first year on the baseball team, the college yearbook was singing his praises: “His feet and hands worked like magic; often before we knew where the horsehide had been batted, Charlie would have it scooped up and on its way to first. At bat he was a terror for the opposition, and whenever he made his appearance, the outfielders could be seen moving outward and at the same time surveying with their eyes the woods in the background. You should set those woods afire before you leave us, Charlie!”[2] During his senior year he was the captain of the varsity baseball team, and won the Laval Medal as the best collegiate athlete in South Carolina. The summer after his graduation from Presbyterian, he once again played on the Clinton Mill team.

Although most sources say that Charlie started his professional career with the Class B Danville Veterans (Three-I League) in 1929, his biography in Thornwell: Its Principles and Product says he first played in Marshalltown, Iowa, in 1927. This would have been the summer before his senior year at Presbyterian College. In 1928 Charlie was playing with Topeka of the Class C Western Association. Paul Richards, later a major-league catcher, manager, and general manager, but then a pitcher for Muskogee, later told writer Arthur Daley an amusing incident that occurred when he faced Charlie: “ ‘We were playing Topeka that day and I pitched right-handed to the rightie hitters and left-handed to the lefties. Then Eddie Dyer, the Topeka manager, sent up Charlie Wilson, a switch hitter.’ Richards toed the rubber as a left-handed pitcher. Wilson switched to the right-handed side of the plate. Richards transferred the glove to his other hand. Wilson crossed to the opposite side. At every switch of the glove by the pitcher, the hitter had a matching maneuver. This continued for so long that the fans began to stomp their feet and clap in derision. The nimble-minded Richards climbed off the horns of that dilemma in a hurry. He discarded his glove and took his position on the mound, the ball held over his head in two bare hands, ready to pitch with either. ‘Okay, wise guy,’ he said to Wilson. ‘What are you gonna do now?’ Wilson was helpless. He had to take his position first before Richards would throw. ‘That’s when it got interesting,’ confessed Paul. ‘I got him on a swinging strike lefty and three or four fouls rightie. There also were some near-misses for balls, some right and some left. When the count reached 3 and 2, I came in with a left-handed curve that just missed the plate. I know I should have struck him out to give this the proper touch of the dramatic. Instead, I walked him. Oh, well. You can’t have everything.’ ”[3]

Wilson was with the St. Louis Cardinals during spring training in 1929. According to the Miami News, “A rookie second baseman, Charlie Wilson led the St. Louis Cardinals’ attack against the Philadelphia Nationals Thursday. … Wilson made four hits for a total of five bases in five times up.”[4] Despite this promising start, the Cards sent him down to Danville, where he played 137 games and sported a batting average of .317 and a slugging percentage of .429.

In 1930 Charlie was with the Rochester Red Wings, a Cardinals Double-A affiliate. He did not start off well. In April the Rochester Evening Journal and the Post Express reported that he was put into a game to replace George Toporcer at second base, and was either directly or indirectly responsible for all of the opponents’ unearned runs. Red Wings manager Billy Southworth lamented to a sportwriter, “That boy … simply must show better than he has to stay with us.” The sportswriter commented, “And that was a big reproach for Billy to make. Wilson’s case is curious indeed. He can throw like a rifle; he’s fast and he can hit, but, except in one game with the Reds, he hasn’t had, apparently, one idea of what the game is all about. Perhaps he is in love.”[5]

This final observation was probably accurate, as Wilson had fallen in love with a Rochester girl, Mary Collins, whom he married the following April. Mary, born in Ireland, was the daughter of James Joseph and Mary Collins, and in 1930 was working as the bookkeeper at a local country club. Her father worked for the railroad, and died tragically several years later when a pile of lumber fell on him.

By July 1930 Charlie was still was still playing with the Red Wings, and had definitely changed his tune, “hitting like nobody’s business,” as well as playing well defensively.[6] He ended the year with a batting average of .300 and a slugging percentage of .464. The Red Wings, with a 105-62 record, won the Junior World Series that year.

Wilson was with the Boston Braves for spring training in 1931. The Braves were all set to pay $30,000 for Charlie had he been successful, and he started out playing well, “performing in a manner that makes even the old-timers blink.”[7] On March 4 he was spiked in the knee by a runner sliding into third, producing a severe cut and keeping him out of action for a while. By late March he was being referred to as the “big flop” of the Braves.[8] He was proving to be a real puzzle for Braves manager Bill McKechnie: “Frankly, McKechnie is worried about third base. Wilson, the high priced recruit from Rochester, is a slick fielder and a fast pegger, but is not an impressive ball player. He lacks the fire that some of his known rivals have when on the ball field. Wilson has done his fielding chores up to advance notices, but he has been weak with the willow, a department in which he is supposed to be particularly strong. Wilson showed up in camp with a trick knee and a cold. McKechnie is impressed with his throwing arm, but can’t account for his poor showing at the bat.”[9]

Wilson did stay with the Braves for the first part of the season, making his major-league debut on April 14. He had the best game of his major-league career on April 28, driving in four runs in five at-bats in a losing effort against the Phillies. All of his best major-league hitting performances came while he was playing for Boston that year. But despite his promising beginning, he was sent back to the Red Wings in early May after appearing in only 14 games. The Red Wings once again won the Junior World Series that year, with a record of 101-67.

By December 1931, Red Wings manager Billy Southworth had decided to switch Charlie from third base to shortstop. Wilson admitted to feeling a little cramped at third base, and Southworth decided that Charlie could “take ’em on the wrong hop as well as anybody.”[10] He played with the Red Wings for most of the 1932 season, but late in August he was called up by the Cardinals. The Rochester Evening Journal wrote, “The Swamp Baby wasn’t ready for his big chance when he had a whirl with the Braves a year ago, but he has acquired poise and polish since that time and Wilson’s work with the Reds has been of a quality that entitles him to promotion to baseball big time.[11] He played in 24 games with the Cardinals that season, the most he would play in a major-league season. He also had his best defensive year, with a fielding percentage of .935.

Wilson was back with the Cardinals in 1933, but injured his back and played in only one game. Then he returned to the minors, first with the Columbus Red Birds, another Cardinals farm team. He was traded to Rochester when the American Association determined that he and four other Columbus infielders were being paid more than the league’s salary cap allowed. He went back to Columbus in 1934, and played 145 games. His batting average that year was .325, and he sported a slugging percentage of .460 and a fielding percentage of .958.

Charlie was back with the Cardinals for spring training in 1935, but he was apparently having difficulty with manager Frankie Frisch. According to the Palm Beach Post, he was sent home to St. Louis in early April for breaking training for the second time.[12] He did play 16 games at shortstop for the Cardinals that year, participating in his final major-league game on May 25. He batted.323 in 33 at-bats, with an on-base percentage of .364 and a slugging percentage of .323. During his four different seasons in the majors, Wilson played 25 games at shortstop and 22 games at third base. He never did perform up to expectation as a batter. He had 186 at-bats, an average of .215, and a slugging percentage of .317. His fielding percentage as a shortstop was .935, and at third base .922. He was released to Rochester on July 16, 1935. The Cards finished in second place in 1935 and even though Wilson was gone by midseason, his teammates voted him a half-share of first-division money.

Wilson’s performance with the Red Wings was not stellar in 1935. He played in 48 games and batted.246 with a slugging average of .306. His fielding percentage, however, was good, at .955. At some point late in the season, he left the Red Wings to manage the Huntsville Red Birds of the Class D Arkansas State League. He was the third of three managers of the last-place team that year, following James Nicely and William Werner.

In December the Rochester club sold Wilson to the league rival Montreal Royals. According to the Rochester Journal, the sale might have been related not to Charlie’s performance, but rather to the poor relationship he and new Red Wings manager Ray Blades had developed when they were together in Columbus.[13] The Sporting News, however, had a different take on things, suggesting that Wilson had behavior problems: “St. Louis club officials have shown sufficient faith in Wilson’s natural ability to keep a string on him and move him forward, as his showing justified. … Wilson would have received his opportunity in due course. Had he shown the proper diligence and attention to self-discipline that chance would have been afforded him. It begins to appear that he has permanently shut the door to his own prospect of advancement.”[14]

Wilson played one season for the Royals, appearing in 110 games and ending the season with a .262 batting average. In February 1937 the New York Giants acquired his contract to have him play for their Jersey City farm club. This was Wilson’s final season in baseball. He played in 137 games for Jersey City and batted .266. During his years in the minor leagues, he played in 1,070 games, had a batting average of .292, and a slugging percentage of .423.

Wilson and his wife, Mary, continued to live in Rochester after he retired from baseball. They had two children, Charles W. Wilson, Jr., born in 1933, and James Collins Wilson, who had Down syndrome, born in 1941. For several years, the Rochester city directories indicate that he was employed as an inspector, although they give no clue as to his employer. By 1944 he was a foreman with General Motors. By 1948 he was working as a traveling salesman. Mary was also employed for much of her life, working for Rochester Products for 30 years. Their son Charles Jr., known as Swampy, died suddenly in 1969 at the age of 36. He is buried with his grandparents, James and Mary Collins, in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Rochester. Charlie Wilson died in Rochester of cardiac arrest on December 19, 1970. He is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester. His wife, Mary, died on June 25, 1995, and is buried in Henrietta, New York, a small town south of Rochester. Buried in the same plot is her son, James Collins Wilson, who died in 2003. In addition to James, Mary was survived by her grandson, James Charles Wilson, and his wife, Pamela; great-grandchildren Jennifer, Rachel, and Tyler; and daughter-in-law Marlene Wilson.

April 29, 2011

Sources

Ancestry.com (Census records, Rochester city directories)

Baseball-Reference.com

Thomas Perry. Textile League Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 1993.

Retrosheet.org

[1] Thornwell Orphanage: Its Principles and Product, 1942: 187.

[2] PacSac. Presbyterian College, 1925.

[3] Arthur Daley. “A Matter of Pitching.” New York Times, June 13, 1954: S2.

[4] Miami News, March 20, 1929: M23.

[5] Reds Present Six Runs to Cardinals.” Rochester Evening Journal and the Post Express, April 8, 1930.

[6] “Rochester Evening Journal, July 19, 1930: 17.

[7] Reading Eagle, March 16, 1931: 12

[8] Berkeley Daily Gazette, March 27, 1931:15.

[9] “Charlie Wilson Puzzle to Bill McKechnie.” Rochester Evening Journal and the Post Express, April 3, 1931: 31.

[10] Rochester Evening Journal and the Post Express, December 16, 1931: 63.

[11] John Burns. “Chance for Swamp Baby.” Rochester Evening Journal, August 12, 1932: 99.

[12] “Several Other Players Disciplined by Frankie Frisch.” Palm Beach Post, April 4, 1935.

[13] “Red Wings sell Charley Wilson to Royals.” Rochester Journal, December 11, 1935.

[14] The Sporting News, April 11, 1935: 4.

Full Name

Charles Woodrow Wilson

Born

January 13, 1905 at Clinton, SC (USA)

Died

December 19, 1970 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.