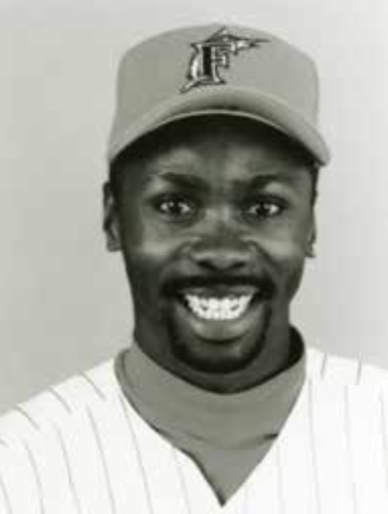

Chuck Carr

Entertaining and irritating by turns, outfielder Chuck Carr was known for his speed and cocky personality. Carr’s running ability was what made him fun to watch. He made many circus catches and stole a lot of bases. That made him a fan favorite in Miami, where he enjoyed his best year in 1993 for the Florida Marlins, as the first-year expansion team was then known. “He was once the Marlins’ first impression, their leadoff hitter, part cartoon and mostly character, the ego and image and swagger of a franchise that had little else.”1

Entertaining and irritating by turns, outfielder Chuck Carr was known for his speed and cocky personality. Carr’s running ability was what made him fun to watch. He made many circus catches and stole a lot of bases. That made him a fan favorite in Miami, where he enjoyed his best year in 1993 for the Florida Marlins, as the first-year expansion team was then known. “He was once the Marlins’ first impression, their leadoff hitter, part cartoon and mostly character, the ego and image and swagger of a franchise that had little else.”1

Carr went through four organizations, getting brief big-league trials with the New York Mets and St. Louis Cardinals before emerging in Florida. “Why did it take him a while to make it?” said Clint Hurdle, one of his minor-league managers with the Mets. “No. 1, he had to refine his baseball skills. And No. 2, it probably took him a while to refine his social skills, as far as maturing and taking responsibility. He’s a free spirit, one with a high evaluation of himself.”2

Carr played just 507 games in a major-league career that ended after spring training in 1998. The switch-hitter had little power, and as it had been during much of his minor-league career, getting on base enough to use his speed was a factor. Various reports also focused on perceptions of Carr’s flamboyant antics. For example, he was named one of baseball’s “top ten jerks” ahead of the 1996 season.3

Yet as much as “Chuckie” may have annoyed teammates, managers, and opponents, he was also likable. In particular, he was always fan-friendly. “It’s out there that I have an attitude problem,” the man himself acknowledged. “Then you hear fans say, ‘He’s a nice guy, he’s down to earth.’”4 Throughout his career, Carr was active in stay-in-school and antidrug programs aimed at children.5 His desire to help others was also visible as he played ball off and on overseas and in independent leagues through 2003. He later became a minor-league coach.

Charles Lee Glenn Carr was born on August 10, 1967, in San Bernardino, California. His father, Charles Lee Carr, was an Air Force veteran who became a Baptist minister while also conducting vocational and rehabilitation work. The elder Carr was a fine athlete too, becoming a Junior Golden Gloves champion in boxing. Known as Charles Benson when younger, he had also hoped to make the Olympic track team in 1964 but tore a hamstring.6

Young Chuckie was a daredevil who enjoyed the sensation of flight. A 1994 feature on Carr described him as a 12-year-old, doing wheelies off the roof of his parents’ house in Fontana, California. He also liked to jump off the same roof onto the diving board of the family’s swimming pool. That article mentioned his mother’s name, Charlene.7 However, no other information is presently available about her or any other children in the Carr family.

Available articles about Carr also do not discuss any other sports he may have played, such as football, basketball, or track. He attended Fontana High School, where he was a year ahead of a future teammate with the Marlins, Greg Colbrunn. Fontana was known as a football school. “The football stadium holds 10,000. The baseball stadium holds a couple hundred,” said the Steelers’ baseball coach then, Steve Hernandez. “When it came to baseball, we didn’t have a fancy operation. It was a rags-to-riches story. … When I got to the school the team had won something like two or three games the year before. But I inherited these two incredible athletes.”

Hernandez added, “Carr thought he was a second baseman. As soon as I took over, I told him he was going to play center field. He told me I must be mistaken. I told him there was a new sheriff in town.” Carr started working on the diving catches that became his trademark, and Hernandez said, “Once in a while I’d get the feeling that Chuck was waiting a second before he started for the ball so he’d have to make the spectacular catch. But I’ll say this much, you haven’t seen anything on ESPN that I didn’t see in our little ball field.”8

By Carr’s senior year, 1986, Fontana was playing Esperanza High of Anaheim in Dodger Stadium for the championship of the California Interscholastic Federation’s Southern Section, division 4-A.9 Just a couple of days later, the Cincinnati Reds selected Carr in the ninth round of the amateur draft. The scout was former big-league reliever Ed Roebuck.

Carr’s pro career got off to an uncertain start. In 44 games of rookie ball in the Gulf Coast League, he hit just .171 and the Cincinnati organization released him. By one report, it depressed the 18-year-old so much that he considered taking his own life.10

In 1987, however, Carr signed with the Seattle Mariners. Reporting to Bellingham of the Northwest League (short-season Class A), he did better with the bat: .242 with a homer and 11 RBIs in 44 games. Getting on base more also enabled him to steal 20 bases. Carr’s natural confidence had rebounded. Allegedly he told his teammate Ken Griffey Jr., then a first-year pro, to find a position other than center field.11 Griffey was already a budding superstar, though; the M’s experimented with Carr at shortstop and second base that season.

Carr also met his wife, Candace Gilbert, that summer on a road trip to Oregon. “We were staying at the same hotel,” Candace (an Arizona native) remembered in 1993. “It was his first road trip, and he’d forgotten to bring underwear. I gave him a ride to the mall. I helped him buy his underwear, he bought me an ice-cream cone, and we`ve been together ever since.”12

Carr lifted his steals total to 62 in 1988. He batted .299 and stole 41 bases in 52 attempts for Wausau of the Midwest League (Class A). That won him promotion to Vermont of the Eastern League (Double A), where he swiped 21 in 30 tries. He hit .281 overall with 7 homers and 43 RBIs. That August 18, he and Candace were married.13

The Mariners traded Carr to the Mets in November 1988 for Reggie Dobie, a pitcher then at Triple A who lasted just one more season in the pros. Carr spent all of 1989 in Double-A ball, posting a line of .241-0-22 in 116 games for Jackson in the Texas League. He stole 47 bases, tied for second in the league, but got caught 20 times.

Carr started 1990 with Jackson again. After batting .306 with six steals in 14 games, he got his feet wet in the majors that April. The Mets called him up to replace injured center fielder Keith Miller.14 Carr pinch-hit in one game; he was returned to Jackson after the Mets acquired Daryl Boston and promoted Darren Reed.15

Carr made it up to Triple-A Tidewater that summer, and in August the Mets summoned him again after outfielder Mark Carreon got hurt.16 The next day, Carr played in the field for the first time as a big leaguer. It was only for the last half-inning in a blowout loss. He appeared twice more in August and went back to Tidewater after the Mets acquired veteran Pat Tabler.17

Carr hit just .195-1-11 in 64 games for Tidewater in 1991, yet he still got some limited action with the Mets. He played in two games in June during a call-up that lasted less than a week. He returned in August when Vince Coleman reinjured a hamstring and landed on the disabled list for the second time that year. Carr appeared nine times and got his first base hit in the majors, a single off Pittsburgh’s Bob Kipper, in a loss at Three Rivers Stadium.

Carr then went on the DL himself.18 He wore the Mets uniform in one more game, on September 26. That November, New York sent him outright to Tidewater. The next month, they traded him to St. Louis for Clyde Keller, a pitcher who never got beyond the low minors and was finished after 1992. The Mets then had a very similar center fielder in their chain: Pat Howell, who also had blazing speed, made many dazzling outfield plays, but had an even harder time reaching base.

To start the 1992 season, Carr went back to Double-A ball. However, minor-league hitting instructor Johnny Lewis helped shorten his swing and he averaged .308 at Louisville after being promoted from Arkansas.19 Between the two levels, he totaled 61 steals. When Ozzie Canseco injured a shoulder, St. Louis called Carr up. He hit .219 in 64 at-bats over 22 games. He also stole 10 more bases.

Reportedly, the Cardinals seriously considered protecting Carr from the expansion draft that November because of his speed.20 That November, however, the Marlins selected him as the 14th pick. It was his big break.

Right around then, Chuck and Candace welcomed their first child, a boy named Sheldon. The blessings of parenthood were hard-won; Candace had had six miscarriages and a baby born prematurely who lived only a few days. “This was a great off-season,” she said at the end of March 1993. “We had the baby, and then Chuck got his first major league chance.”21

Scott Pose, a Rule 5 pickup, was Florida’s starting center fielder and leadoff hitter to begin the 1993 season. By mid-April, however, Carr had taken both spots. In May, The Sporting News wrote, “Carr emerged as a genuine leadoff threat, stealing three bases twice in a game and 10 in April. Carr, who may be the fastest player in the league, is erratic in the outfield but gives the team its one disruptive force on the basepaths.”22

Carr used his speed another way: He put 42 bunts in play that year, getting 17 base hits.23 One notable example came on July 28 at Shea Stadium in New York. In the ninth inning of a 3-3 tie, acting on his own, he beat out a two-out drag bunt to bring in the go-ahead run.24 Anthony Young stood to lose his 28th straight decision, but the Mets rallied for two in the bottom of the ninth against closer Bryan Harvey, finally snapping Young’s record losing streak.

Carr led the National League in 1993 with 58 steals, although he got caught a league-high 22 times. In contrast to the earlier report, he was routinely making great catches. STATS Inc.’s Scouting Report for 1994 wrote, “With Andy Van Slyke out for half the season, Carr dominated the highlight shows; every other night, it seemed, he was making another spectacular diving catch.”25

In September 1993, Miami Herald writer Dan Le Batard said, “Chuck Carr catches balls no one else touches.” However, he quoted Van Slyke, who had won five straight Gold Gloves in the outfield, as predicting that Carr would not get one because the NL’s coaches and managers wouldn’t vote for a hot dog. While acknowledging Carr’s range, Van Slyke said, “Coaches like guys who don’t draw extra attention to themselves. Chuck gives them reasons not to vote for him. His whole package tends to offend.” Darren Lewis (Van Slyke’s pick) and Marquis Grissom (one of the eventual winners) were mentioned. Yet in Le Batard’s view, while both were as worthy as Carr, neither was as wonderful. Marlins manager René Lachemann said flatly that Carr was the best center fielder he had ever had. “There is nobody who covers more ground than Chuck Carr,” Lachemann said. “Nobody I’ve seen.” 26

Le Batard also observed, “Never mind that fans love Carr’s flair, love the color he brings to a game that can be as black and white as its box scores. There is no one in the league who does what Carr does, no one who can make the home crowd rise on a ball the other team hits into the gap … who plays with such reckless disregard for his health.”27 Around the same time, Carr won a “Your Favorite Marlin” contest conducted by the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel.28

After a contract holdout in the spring, Carr tempered his baserunning in 1994. He stole 32 bases in the strike-shortened season and got thrown out just eight times, but he had mixed feelings about it. That June, he said, “I feel like I’m learning and becoming a better ballplayer. At the same time, I kind of liked the old me, my wild style of play. I was real aggressive, real wild on the bases. I don’t feel that wildness in me. It takes a little fun out of the game.” That report also observed that the Marlins didn’t like Carr’s arrogance and independence, and that the team was likely to deal him as soon as Carl Everett was deemed ready.29

Carr’s woofing, strutting, and taunting were the talk of the National League. Marlins first baseman Dave Magadan noted that when opposing players reached base, the “pedigree hot dog” was the primary topic of conversation. “They ask how we can stand being around that guy,” said Magadan. “I just smile and shrug. Chuck’s all right if you’re playing on the same team. To the other team he’s an irritant, because he’s always jumping around, always has a big smile on his face, having fun at your expense.’”30

Whereas in 1993 Carr hit leadoff for all but two-at-bats, in 1994 René Lachemann used him in the number-two hole frequently and even dropped him down to eighth for several games. Carr’s on-base percentage slipped from .327, already subpar, to .305. He wanted to be like Brett Butler, who also had little power yet was a consummate leadoff hitter (lifetime OBP .377). Butler was also a superior bunter, and shortly before the strike Carr noted that he’d been thinking about getting back to bunting more (though a later scouting report said he didn’t do it particularly well).31

In the winter of 1994-95, the Marlins sent Carr to play in the Dominican Republic, challenging him to prove that he could be a good leadoff hitter — or plan to bat eighth in the order in 1995. Six games into the season, however, the Licey Tigres kicked Carr off the team after discovering that he had been banned for five years from playing in Latin American winter leagues. That stemmed from his decision to leave Hermosilla, in Mexico’s Pacific League, in 1991.32

That same report noted that Carr sought permission from the players union to work with the Marlins’ new hitting coach, José Morales. The potential job challenge from Carl Everett was mentioned again. In late November, however, Florida traded Everett to the Mets. Thus, Carr remained the team’s primary center fielder in 1995. He played in 105 games, starting 77 and batting mainly in the number-two spot. Though his average slid to .227, he did draw more walks and got his on-base percentage up to a career-high .330. He stole 25 bases and was caught 11 times.

That November, the Marlins signed Devon White, a seven-time Gold Glover in center field, to a three-year contract worth $10 million. The Sporting News observed, “He not only gives them speed and defense in center, but also a legitimate bat that the enigmatic Chuck Carr could not provide in three seasons.”33 Florida also opted to keep Jesús Tavarez, a younger player who was out of options, as the backup center fielder.34

Soon thereafter, the long-awaited Carr trade finally took place. Florida dealt him to the Milwaukee Brewers for a minor-league pitcher named Juan González. Brewers general manager Sal Bando said he wasn’t worried about Carr’s clubhouse reputation. “He rubs some people the wrong way, but fans love him and he plays hard. Do you want a bunch of nice guys that lose?”35

Carr started strongly for Milwaukee. He was “giving us an identity, a spark at the top of the lineup,” said manager Phil Garner. “He got on and he made things happen and he was making great plays defensively.”36 However, Carr played just 27 games in 1996. First, he strained a hamstring in April and went on the 15-day disabled list. Then, on May 30, he tore up his right knee making a sensational catch on the warning track. He landed awkwardly and bent the knee backward. He underwent surgery to repair two major ligaments, a hamstring tendon that was ripped from the bone, and a deep bone bruise. “The only thing keeping the knee together was the skin,” said Brewers trainer John Adam.37

The injury ended Carr’s season, but his return after the gruesome blowout was remarkably swift. By October, he knew he’d be back because he could dunk a basketball.38 He beat out Gerald Williams for the starting job in center field in 1997. But after getting just one hit in his first 16 at-bats, he was benched. Sal Bando later said that Carr’s attitude became a distraction, and that the front office didn’t think he looked the same as he had in 1996. According to Phil Garner, though Carr was playing the field with his usual abandon, the knee affected his swing from the left side.39

Carr started just six games from April 7 onward. His time in Milwaukee ended after one of those starts, on May 16. The story of his release has become a minor legend. As he led off the bottom of the eighth inning, the Brewers trailed the California Angels 4-1. Carr got the take sign with the count in his favor. Instead, he swung away and popped up. Garner, who’d already had a one-hour, closed-door talk with Carr that month, confronted him about it after the game. Carr’s response (as reported in the press): “That ain’t Chuckie’s game. Chuckie hacks on 2 and 0!”40

“I swear to God, that’s what he said,” Garner remarked later that month. “The guy is always talking about himself in the third person, which often gets you one of those white jackets that ties in the back.”41

However, Carr — whose average had dropped to .130 after that last hack — denied the quote. The following year, he said, “It was just time to leave. I wanted to get out of there. I still felt like I could be a spark somewhere. I could’ve kept my mouth shut and taken the money. That wasn’t my role. I asked, can they release me.” Indeed, the Brewers let him go after he refused an assignment to Triple A, forfeiting the rest of his $325,000 salary. “I had to put everything on the line,” said Carr. “But I believed. I felt like there was a team out there that needed me.”42

There was — at the beginning of June, he signed as a free agent with the Houston Astros. He played for a few weeks with Triple-A New Orleans, and then the Astros called him up. Carr got into 63 games over the remainder of the season, starting 48 of them, and hitting .276-4-17 while also playing his usual exciting style of center field. Early that August, he returned to Florida to play against the Marlins for the first time after they traded him. The fans received him warmly, and Carr also said that he’d grown up.

“I was still living that kid life when I was here,” he remarked. “People wanted me to be an adult, but I wasn’t ready for that. That’s different now. Believe me, I’m not the same person I used to be.” Nonetheless, he added, “I look back and don’t have any regrets. None at all. I’m serious. People don’t like the fact that I’m so positive. I have a lot of confidence and expect big things. That’s just the way I am. I’ll never change.”43

Carr got his only taste of major-league postseason play in 1997. He appeared in two of three games in the National League Division Series and went 1-for-4 as Atlanta swept Houston. He started Game Three, hitting a solo homer off John Smoltz.

Although Carr had played reasonably well in Houston, he did not get a contract offer and was granted free agency on December 21. The very next day, the Astros obtained their new starting center fielder — Carl Everett. It was ironic because Everett’s odd behavior made Carr’s look mild.

Carr never played again in a regular-season big-league game. The Montreal Expos invited him to spring training in 1998 on a minor-league contract, but he did not win a job.44 He then went to Taiwan, joining the Mercuries Tigers. In 36 games, he hit .308-3-12 and stole 15 bases.

That July, the Carrs’ fourth child was born prematurely, and Chuck decided that he would rather be with his family than continue playing in Taiwan. He told the story of the baby’s fight for survival. “My oldest son, Sheldon, named him. He said, ‘Mommy, let’s call him Chance,’ because all he had was a chance. It was iffy.”45 One of the two middle children was named Aeron; research has not turned up the name of the other.

Carr still wanted to keep his baseball dream alive, though, so in 1999 he joined the Atlantic City Surf of the independent Atlantic League. Eric Davis, an old friend from Southern California, told him to keep following his passion until someone came and snatched the uniform off his back. Carr also said that his kids were getting tired of having to share video games with him!46

Carr hit .263-8-21 in 49 games for the Surf and was regarded as genial, self-effacing, and popular. The self-effacing part stood in contrast to the past, but late that season, he said, “Life is about making mistakes, correcting them and going on and learning.”47

A different Atlantic League team, the Long Island Ducks, began operations in 2000. The team’s manager and part-owner, Bud Harrelson, had been Carr’s skipper with the Mets in 1990 and 1991. Carr became the first player to sign with the Ducks. He was there to help himself, saying, I really believe teams are going to see how much I’ve matured as a ballplayer and as a man.” However, he also expressed a desire to mentor younger players, as veterans such as Garry Templeton and Hubie Brooks had helped him when he was breaking in.48 Carr hit .253-10-48 with 28 steals in 73 games for the Ducks. It does not appear that he got any feelers about returning to the majors.

Carr was out of pro ball in 2001. He then went abroad again in 2002, joining Rimini of the Italian Baseball League.49 Rimini won its fourth consecutive Serie A/1 pennant, and Carr played a key role as his team overtook Bologna, which led Rimini by two games with six to play. Rimini then swept a three-game series from Bologna, as Carr went 6-for-12 with two homers. Even though the teams finished with identical records, Rimini was awarded the pennant because its head-to-head record against Bologna was 4-2.50

Carr gave it a last shot in 2003 as a player-coach with the Bisbee-Douglas Copper Kings of another indie circuit, the Arizona-Mexico League. (The Carr family had made its residence in Mesa, Arizona.) “He’s looking to get back into Organized Baseball as a running coach,” said Bisbee-Douglas general manager John Guy. “He still thinks he can play.”51 Carr was the four-team league’s biggest name. In 14 games, he hit .365-1-8. The Copper Kings and the Nogales Charros both ran out of money, though, and so the league folded in mid-June, just 16 games into its schedule.

Carr rejoined the Astros organization in 2004. He was a coach with one of Houston’s farm teams, the Salem Avalanche (Carolina League, high Class A), from 2005-2007. Since then, he was out of the public eye, although he did participate in private memorabilia signings. Nonetheless, his name still popped up now and again. In 2017, the Miami New Times ran a column called, “Twenty Ways to Tell if You’re a True Miami Marlins Fan.” Number 18 was “About every five seasons, you ask someone out of the blue: ‘Hey, remember Chuck Carr?’”52

After a battle with cancer, Chuck Carr died at the age of just 55 on November 12, 2022.

Other Sources

https://twbsball.dils.tku.edu.tw/wiki/ (Taiwanese baseball website).

Notes

1 Jeff Miller, “Carr Still Drawing Crowds in Florida,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, August 5, 1997.

2 Gordon Edes, “Carr Usually Flies in Steering Marlins,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, April 3, 1994.

3 Steve Rushin, “Bad Behavior,” Sports Illustrated, March 12, 1996. The others identified by a survey of baseball writers across the country were Albert Belle, Barry Bonds, Steve Howe, Kevin Brown, Lenny Dykstra, Will Clark, Eddie Murray, Danny Jackson, and Bip Roberts. See also “Belle, Bonds, Clark Make All-Jerk Team,” San Francisco Examiner, March 9, 1996.

4 Mark Herrmann, “Ex-Met Carr to Become First to Sign with Ducks,” Newsday, April 11, 2000.

5 “Brewers’ Carr Is Going Full Speed Ahead,” Amarillo Globe-News, March 11, 1997.

6 “Rehabilitation Service Opens Fontana Facilities,” San Bernardino County Sun, April 28, 1974: 79. “Brewers’ Carr Is Going Full Speed Ahead.”

7 Edes, “Carr Usually Flies in Steering Marlins.”

8 Geoff Calkins, “Carr, Colbrunn Revisit,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, April 7, 1994.

9 Scott Howard-Cooper, “Southern Section Baseball Finals: Fontana Tries to Complete Improbable Finish Tonight,” Los Angeles Times, May 31, 1986.

10 Herrmann, “Ex-Met Carr to Become First to Sign with Ducks.”

11 Ibid.

12 John Hughes, “Years of Perseverance Pay Off in Big-league Debut for Parents,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, March 31, 1993.

13 Trevor Jensen, “Carr’s Wife Files for Support but Not Divorce,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, April 7, 1994.

14 “Mets call up Carr, send Jeff] Innis to minors,” White Plains (New York) Journal News, April 26, 1990: 41.

15 “Transactions,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald and Review, May 1, 1990, 14.

16 “Gooden’s 10-1 Spurt: ‘Right Now, I Stink,’” The Sporting News, September 3, 1990: 10.

17 “Mets Acquire Phillies’ Tom] Herr,” Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, September 1, 1990: 42.

18 “Transactions,” Port Huron (Michigan) Times Herald, August 30, 1991: 14.

19 Rick Hummel, “St. Louis Cardinals,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1992: 22.

20 Ibid.

21 Hughes, “Years of Perseverance Pay Off in Big-league Debut for Parents.”

22 Gordon Edes, “Carr Gets Used to Leading Role,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1993: 18.

23 “Opposite Attractions,” Palm Beach Post, April 3, 1994. John Dewan and Don Zminda, editors, The Scouting Report, 1994 (New York: HarperCollins Publishing), 450.

24 Ed Giuliotti, “Marlins Help Mets End Young’s Slide,” Orlando Sentinel, July 29, 1993: D3

25 Dewan and Zminda, The Scouting Report, 1994; Gordon Edes, “Florida Marlins: Analyzing 1993,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1993: 16.

26 Dan Le Batard, “Marlins’ Carr Is Gold Glove — with Flair,” Miami Herald, September 5, 1993. It was not until 2011 that the Gold Gloves for outfielders again specified awards for left fielder, center fielder, and right fielder. From 1961 through 2010, three outfielders were selected irrespective of their specific position (see “Gold Glove History” at Rawlings.com). As it turned out, the 1993 NL Gold Glove outfielders actually did play separate positions: Grissom (CF), Barry Bonds (LF), and Larry Walker (RF).

27 Ibid.

28 Gordon Edes, “Smooth-Running Carr,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1993: 20.

29 Amy Niedzielka, “Jeff] Conine Cookin’,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1994: 21.

30 Larry Guest, “Carr’s Confidence Rises with Batting Average,” Orlando Sentinel, June 12, 1994.

31 Dave Hyde, “To Avert Nightmare, Carr Better Wake Up,” Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, July 31, 1994. Gary Gillette, Stuart Shea, and Pete Palmer, editors, The Scouting Report: 1996 (New York: HarperCollins Publishing, 1996), 417.

32 Amy Niedzielka, “Carr Suspended,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1994: 40.

33 Scott Tolley, “Devon Intervention,” The Sporting News, December 4, 1995: 47.

34 Scott Tolley, “Carr Out, Joe] Orsulak In,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1995: 44.

35 Drew Olson, “Fast, New Carr,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1995: 48.

36 “Indians 2, Brewers 0,” United Press International archives, May 30, 1996.

37 “Brewers’ Carr Is Going Full Speed Ahead.”

38 Cheryl Rosenberg, “Carr Proved Doctors Wrong,” Palm Beach Post, August 5, 1997: 29.

39 “Carr Refuses Triple-A, Gets Released,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), May 22, 1997.

40 Ibid.

41 “Carr Swerves Out of Job,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 28, 1997: 17.

42 Rosenberg, “Carr Proved Doctors Wrong.” “Carr Refuses Triple-A, Gets Released.”

43 Miller, “Carr Still Drawing Crowds in Florida.”

44 “Transactions,” New York Times, February 4 and March 31, 1998.

45 Mark Herrmann, “It’s Looking Ducky,” Newsday, April 22, 2000.

46 Mark Herrmann, “Ex-Met Carr to Become First to Sign with Ducks.”

47 Ibid.

48 Herrmann, ““It’s Looking Ducky.”

49 Harvey Sahker, “Some Familiar Names,” Baseball America, May 14, 2002.

50 Harvey Sahker, “Rimini Continues Dominance,” Baseball America, September 27, 2002.

51 Ken Brazzle, “Arizona-Mexico League,” Tucson Citizen, May 6, 2003.

52 Ryan Yousefi, “Twenty Ways to Tell if You’re a True Miami Marlins Fan,” Miami New Times, June 16, 2017.

Full Name

Charles Lee Glenn Carr

Born

August 10, 1967 at San Bernardino, CA (USA)

Died

November 12, 2022 at Mesa, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.