Lenny Dykstra

“(For Dykstra) no dare was too bold, no drink too strong, no car too fast, no poker hand too big.”

“(For Dykstra) no dare was too bold, no drink too strong, no car too fast, no poker hand too big.”

— Jeff Pearlman, author of The Bad Guys Won!1

“The Dude would be an experience even if it had nothing to do with baseball. You could meet the Dude away from the field and come away dazed and confused as to what had just happened.”

— Phillies teammate Terry Mulholland2

“I wouldn’t call the Dude over to help me put a jigsaw puzzle together, but the guy was born to play baseball.”

— Phillies teammate Mitch Williams3

The Houston Astros led Game Three of the 1986 National League Championship Series, 5-4, over the Mets with a runner on and one out in the bottom of the ninth inning. The Mets’ skinny, 160-pound center fielder Lenny Dykstra stepped up to the plate and cranked Houston closer Dave Smith’s 0-and-1 fastball over the wall in right field to give the Mets an improbable 6-5 victory. Dykstra leapt onto home plate amidst a sea of ecstatic teammates.

Seven years later, the Philadelphia Phillies and Atlanta Braves were knotted at 3-3 in Game Five of the 1993 NLCS. In the top of the 10th inning, Philadelphia’s bulky, muscular, 200-pound center fielder Lenny Dykstra stepped to the plate and crushed Atlanta closer Mark Wohlers’ 3-and-2 pitch over the wall in right center to give the Phillies a 4-3 lead that proved to be the final score. As Dykstra rounded third and slapped hands with third-base coach Larry Bowa, he yelled “DIDN’T I???” as if he had called his own shot.

In March of 2012, Dykstra stood in a different arena — a Southern California courtroom. The graying, middle-aged Dykstra was there to receive a sentence of three years in a California state prison for grand theft auto and providing a false financial statement. It was hardly his first encounter with the court system.

Lenny Dykstra always lived for the action. He went a million miles an hour, whatever the venue. He played hard, on and off the field, before, during, and after his major-league career. The attitude and tenacity that allowed him to become an all-star outfielder and build financial success in his post-playing days also likely shortened his playing days, ruined his finances, sent him to prison, and nearly cost him his life. Dykstra is many things, but boring has never been one of them.

Leonard Kyle Dykstra was born on February 10, 1963, in Santa Ana, California, to Jerry and Marilyn Leswick. He was the middle of three sons born to the couple, joining older brother Brian and younger brother Kevin. Three of his Leswick uncles played in the National Hockey League in the Original Six era. Jerry Leswick left his family when Lenny was a toddler. At about the same time, Marilyn met a man named Dennis Dykstra while both worked for the Pacific Telephone Company. Dennis was recently divorced and had three young daughters. The couple married and became a Brady Bunch-type family, with the boys taking the Dykstra surname when formally adopted by Dennis.

Given what the world would come to know of him, it is unsurprising that Dykstra was mischievous as a youth. One of his favorite stunts was stealing a fire extinguisher and spraying people outside Disneyland from the passenger seat of a car.4 The mischief also included getting busted sneaking into Angels Stadium on Christmas Day and playing around on the field.

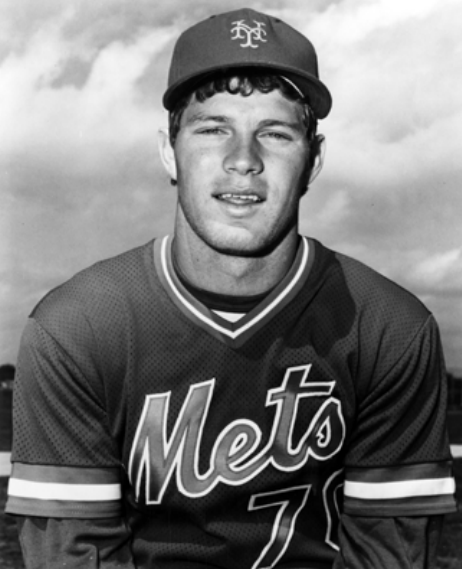

Dykstra wasn’t much for books or studying, but he did find time in school to play football and baseball. During his freshman year at Garden Grove High School, Lenny became the first and only freshman to play on the varsity squad. Before the major-league draft in his senior year, 1981, he went to a Mets tryout camp. Asked by a Mets employee if he was the batboy, Dykstra retorted some version of “I’m Lenny Dykstra and I’m the best player you’re going to see today.”5 The Mets liked what they saw enough to draft Dykstra, but waited until the 13th round because they were convinced other teams were not very interested in him. (The Mets’ 12th-round pick was a pitcher from Texas named Roger Clemens. … He did not sign with the team.)

Dykstra had committed to play baseball at Arizona State and was not happy about being drafted so low. He eventually did sign with the Mets, but insisted that he was too good for rookie ball and should be sent directly to Class A. He won this battle with the Mets, and spent the rest of 1981 and all of 1982 with the Shelby Mets of the Class-A South Atlantic League.

In 1983 Dykstra really began to assert himself as a prospect. Playing for Lynchburg of the Class-A Carolina League, he hit .358 with a .472 on-base percentage and stole 105 bases on his way to league MVP honors. The next year, 1984, Dykstra put up another productive season, becoming the first player in the history of the Double-A Jackson franchise to score more than 100 runs in a season. For good measure, he met his future wife, Terri, while playing in Jackson. The couple married in 1985.

Dykstra spent the first month of the 1985 season with Triple-A Tidewater, but was called up to the Mets in early May and made his major-league debut on May 3. He led off and played center field against the Reds in Cincinnati. Dykstra got Lenny notched his first-major league hit in his second at-bat, a home run off Reds starter Mario Soto.

For the year, Dykstra played in 83 games, platooning in center with Mookie Wilson. About three-quarters of his plate appearances came against right-handed pitching, and his first big league hit turned out to be his only home run of the season. The Mets won 98 games in 1985, but finished three games behind the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League East, New York’s second consecutive season of 90 or more wins that ended with a second-place finish and no playoffs.

Perhaps stung by coming up empty with good teams two seasons in a row, the Mets blew the doors off the NL East in 1986. They reached first place in the division 10 games in and never trailed again, posting a 108-54 record and winning the East by 21½ games.

The Mets were not just legendary on the field. They were notorious for their raucous, partying ways off the field as well. With a few exceptions, the squad ferociously attacked alcohol, drugs, chasing women, and every other activity young men with disposable income are susceptible to. The 23-year-old Dykstra was an important cog on and off the field. He remained a platoon player in center field with Mookie Wilson, but saw his playing time increase as Wilson missed significant time to injury. Dykstra hit .295 with a .377 on-base percentage and swiped 31 bases. He combined with second baseman Wally Backman to form a gritty 1-2 punch atop the Mets lineup and routinely wreaked havoc on opposing pitchers and defenses while setting the stage for the likes of Darryl Strawberry, Keith Hernandez, and Gary Carter. Away from the field, Dykstra was one of the boys, with a particular affinity for gambling until the sun came up.

While the Mets were never seriously challenged in the regular season, the playoffs were a different matter. In the National League Championship Series, New York took on the NL West champion Houston Astros. But perhaps more than the Astros, the Mets took on one Astro in particular: pitcher Mike Scott. The former Met had had a relatively pedestrian career until he learned to throw a split-fingered fastball. The movement on the pitch left many around the league convinced that Scott was illegally scuffing the baseball. The Mets were among the believers.

Scott started Game One of the NLCS and was untouchable, pitching a shutout with 14 strikeouts. The performance only further established Scott’s place deep inside the Mets collective psyche.

The Mets won Game Two and then in Game Three trailed 6-5 going to the bottom of the ninth when Dykstra’s two-run shot off Astros closer Dave Smith rescued the game and put them up in the series. In Game Four Scott again shut down the Mets, this time allowing one run in another complete game. Game Five went to the Mets, sending the series back to Houston for an epic Game Six. The Mets had the chance to close out the series, but the specter of Mike Scott pitching a decisive Game Seven hung over the entire affair.

The Mets trailed 3-0 going in to the ninth inning when Dykstra led off as a pinch-hitter. He tripled to center and scored the first Mets run in a rally that tied the game. The teams traded single runs in the 14th, and then the Mets pushed three across in the 16th inning, punctuated by Dykstra’s RBI single. With the Mets up 7-4, the Astros scored twice before Mets reliever Jesse Orosco struck out Kevin Bass to end it. The Mets were headed to the World Series.

For the NLCS, Dykstra led the Mets in batting, on-base, and slugging averages, and was the only Met to homer aside from Strawberry. While he may have been the Mets’ best player in the series, MVP honors went to Mike Scott.

The Mets went on to defeat the Boston Red Sox in an equally epic seven-game affair. Dykstra again was central to the action, leading off Game Three in Boston with a home run off Oil Can Boyd to set the stage for a four-run first inning and a 7-1 win. He added another homer the next day, this time a two-run shot off Red Sox reliever Steve Crawford. Dykstra was one of six Mets to play in all seven games, hitting .296 with the two home runs, three RBIs, and four runs scored.

The 1987 and ’88 seasons went about the same as 1986 for Dykstra. He was a valuable, productive, and popular player for the Mets, but he was never able to shake the platoon label or usage by his manager Davey Johnson. He never exceeded 500 plate appearances in a season with the Mets, despite his consistent production and no time lost on the disabled list. The 1988 Mets again won 100 games, but were shocked in a seven-game NLCS loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Increasingly unhappy with his role as a part-time player for the Mets, Dykstra was traded on June 18, 1989, with relief pitcher Roger McDowell to the Philadelphia Phillies for infielder Juan Samuel. Free of the limitations placed on him in New York, Dykstra started 85 games the rest of the season and struggled as he never had in the majors. He hit only .222 with the Phillies and scuffled to a sub-.300 on-base percentage, both marks well below anything he had posted in his time with the Mets.

Coming into the 1990 season, Dykstra knew he would have his first real chance to be an everyday major-league center fielder. He responded to the opportunity by putting together his finest season to date, leading the National League in hits and on-base percentage, and making his first All-Star Game appearance as the starting center fielder for the NL team. He flirted with .400 for a while in early summer, but dismissed his chances, saying, “If I hit .400 this year, the world will end. It can’t be done, not with forkballs and relief pitchers and the schedule. I saw a lot of Rod Carew while I was growing up in Anaheim, and if he couldn’t do it, I sure as hell can’t. It’s hard enough just hitting four out of 10 balls, much less hitting them to where people ain’t even standing.”6 Dykstra finished the season at .325 with 9 home runs and career highs in RBIs (60) and stolen bases (33).

He also entered the 1990 season having added about 30 pounds of muscle in the offseason. He attributed the gains to “special vitamins,” even at the time seen as a smirking, winking nod to steroid use.

As the 1991 season began, Dykstra was coming off an All-Star season in his first full year as an everyday player. The 1991 season was, however, a disaster. Dykstra’s enjoyment of high-stakes poker games led to a spring-training meeting with Commissioner Fay Vincent that resulted in a stern warning to keep away from such activities. After never having been on the disabled list before, Dykstra missed two large segments of the season. In early May he nearly killed himself and Phillies catcher Darren Daulton when he drunkenly wrecked his sports car after teammate John Kruk’s bachelor party. Dykstra escaped with broken ribs, a broken collarbone, and a broken cheekbone, and Daulton suffered similar injuries. Dykstra missed nearly two months. Then in late August his season ended after he broke his collarbone again running into the outfield wall in Cincinnati. When he did play in 1991, Dykstra a productive, finishing the season with a .297 batting average and 24 stolen bases in 63 games played.

The 1992 season did not start much better. Leading off the Phillies’ season at home on Opening Day, Dykstra was hit on the wrist by a pitch from the Cubs’ Greg Maddux, breaking a bone and missing the next two weeks. A broken bone in his finger in August again ended his season prematurely. He played in 85 games and hit .301. For the 1991 and 1992 seasons, the Philadelphia Phillies were 76-72 with Dykstra playing and 72-104 without him. If he could ever stay healthy atop the Phillies’ lineup, which finished second in the NL in runs scored in 1992, the team could realistically compete for a playoff spot.

In 1993 everything came together for the Phillies. They got out of the gate with a 17-5 record and never looked back, winning their first NL East title and playoff berth since 1983. They never trailed after April 9, and led by as many as 11½ games with a final margin of three.

For his part, Dykstra had a career year. He played in 161 games, missing only the game after the Phillies wrapped up the division. He hit .305 with 19 home runs, 66 RBIs, and 37 stolen bases, all career highs. His 143 runs, 194 hits, and 129 walks all led the NL. If not for an otherworldly season by the Giants new star, Barry Bonds, Dykstra would have been the Most Valuable Player in the league. One sour note: Dykstra was left off the National League All-Star team.

The Phillies’ run to the playoffs was surprising to most observers. The team gained attention for its scraggly beards and shaggy hair, with more than one or two mullets prominent throughout the season. The colorful cast of characters included grown men known by nicknames such as Dutch, Wild Thing, Inky, Schil, and the doubly-dubbed Dykstra, known as either Dude or Nails.

“Dude” was a fairly straightforward moniker, ostensibly attached because of Dykstra’s inability to complete a sentence without using the term. “Nails” was more descriptive, as in “tough as.” Nails is a statement to the entire world that the bearer of the name was not one to be taken lightly or underestimated. Nails is tough, rugged. Nails would run into the wall to make a play. Nails would never stand for leaving the game with a clean uniform, but would scrap and fight for every pitch, every play of every game. Nails is hard-nosed and hard-working, and has the scrappy, underdog attitude needed to become a fan favorite in two of the most demanding sports cities in the world. Nails played hard all the time, on and off the field.

As the 1993 major-league playoffs dawned, Dykstra was known to the baseball world, but he was about to loudly announce his presence on the game’s biggest stage. The Phillies entered the National League Championship Series as decided underdogs against the two-time defending NL champion Atlanta Braves.

The teams traded blows through the first four games, leaving the series tied for game five in Atlanta. The Phillies led 3-0 entering the bottom of the ninth, when the Braves stormed back to tie it. Batting second in the top of the 10th, Dykstra hit a homer off Mark Wohlers, providing the winning run for the Phillies in the pivotal Game Five. The Phillies clinched the series in the next game. For the series Dykstra hit .280 with five walks, two home runs, and five runs scored.

The 1993 World Series is best remembered for Joe Carter’s series-ending home run off Mitch Williams in Game Six, but the Phillies’ loss could not be pegged at all on Dykstra. He hit .348 with a .500 on-base percentage, scored 9 runs, hit 4 home runs, and stole 4 bases. In the wild 15-14 Game Four Toronto victory, Dykstra went 3-for-4, scored four runs, hit a double and two home runs, stole a base, and drove in four runs. After the season Dykstra was rewarded with a four-year, $25 million contract extension. How did Dykstra view his 1993 performance? “I basically went from star to superstar,” he said. “I basically proved I’m more than the best leadoff hitter in the game. It’s nice to have that recognition, but I’m more than a leadoff hitter. I proved I’m the impact player I’ve always considered myself to be, a situation hitter capable of getting the home run, double, walk, whatever the situation requires. I’ve worked hard and made myself into one of the top five players in the game. Do they pay leadoff hitters what they’re paying me?”7

“He was a red-light player,” said former Phillies coach John Vukovich. “But he was a horrible 10-2 player. What I mean is, he hated to play in a 10-2 game, whether we were ahead or behind. He’d lose focus. He only wanted to play with the game on the line all the time.”8

Dykstra gained a reputation as a money player. In the modern era of sabermetrics, the idea of a player being “clutch” — to rise up and play his best when it matters most — is generally dismissed. But the numbers with Dykstra tell a different story. In his 1,278 regular-season games, Dykstra hit a home run every 56 at-bats, and posted a slash line of .285/.375/.419, with a .793 on-base plus slugging (OPS). In his 32 playoff games, he hit a home run every 11 at-bats, with a slash line of .321/.433/.661 and a 1.094 OPS. The merits of clutch will remain debatable, but if any player has ever been clutch, it is Lenny Dykstra.

After the World Series whispers began to surround Dykstra, his bulked-up physique in particular. The formerly lithe and sinewy Dykstra was by now a beefy fireplug with a thick neck and rippling biceps. Anyone who had seen him over the course of a few seasons saw an obvious change in his physical appearance. Media outlets speculated on the cause of Dykstra’s transformation.9

In 1994 and ’95 Dykstra made the All-Star teams, but his production and health never again matched the lofty heights seen in the magical season of ’93. He missed a month of the strike-shortened 1994 season with appendicitis, and missed more than half of ’95 with a variety of ailments.

In 1996, at age 33, Dykstra left a May game against the Dodgers in the fifth inning and never appeared in a major-league game again. He was diagnosed with spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the spinal canal, and missed the rest of 1996 and all of ’97 before a short-lived comeback attempt in spring training in 1998 put the final end to his baseball career. MLB’s 2007 report on steroids in baseball, led by former Senator George Mitchell, identified Dykstra as having admitted to the commissioner’s office in 2000 that he used steroids during his career.10

After his playing days, Dykstra ran a chain of car washes in California, and seemed to be adjusting well to life after professional baseball. In the mid-2000s, in an odd twist, Dykstra began to emerge as a respected voice in the world of Wall Street stock picking. He was given a column by Jim Cramer of Mad Money TV fame.

By 2009, after a series of poor business deals and financial decisions turned sour, Dykstra had filed for bankruptcy protection. The sprawling map of plans turned bad included the purchase of a Southern California estate once owned by hockey great Wayne Gretzky, a high-end magazine aimed at professional athletes, and more spurned friends, associates, and even family members than anyone should have in a lifetime.

The number of cases and the litany of charges and countercharges are too long and complicated to enumerate. In 2012 Dykstra was sentenced to prison for what amounted to selling property that was to remain under the control of his bankruptcy trustee. He was released in the summer of 2013, after which he completed his court-mandated 500 hours of community service and resided with his ex-wife Terri, who had no plans to remarry him.11

Two of his three sons, Cutter and Luke Dykstra, played in the minor league systems of the Washington Nationals and Atlanta Braves, respectively.

The next chapters in Lenny Dykstra’s life are anyone’s guess. But if those already written tell us anything, they are likely to be anything but boring.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the text, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won! (New York: Harper Collins, 2004), 151.

2 Robert Gordon and Tom Burgoyne, More Than Beards, Bellies, and Biceps (New York: Sports Publishing, 2002), 207.

3 Gordon and Burgoyne, 208.

4 Christopher Frankie, Nailed! (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2013), 16.

5 Frankie and Pearlman give variations of the same quote. Pearlman’s was the adult version. The spirit of the quote is identical in both sources.

6 Steve Wulf, “Off and Running,” Sports Illustrated, June 4, 1990.

7 Ross Newhan, “In Your Face, If Not Your Hair,” Los Angeles Times, March 20, 1994.

8 Gordon and Burgoyne, 208.

9 George Mitchell, “Report to the Commissioner of Baseball of an Independent Investigation Into the Illegal Use of Steroids and Other Performance Enhancing Substances by Players in Major League Baseball.” (files.mlb.com/mitchrpt.pdf).

10 Mitchell, 150.

11 Richard Sandomir, “Lenny Dykstra: Out of Prison and Still Headstrong,” New York Times, August 3, 2014.

Full Name

Leonard Kyle Dykstra

Born

February 10, 1963 at Santa Ana, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.