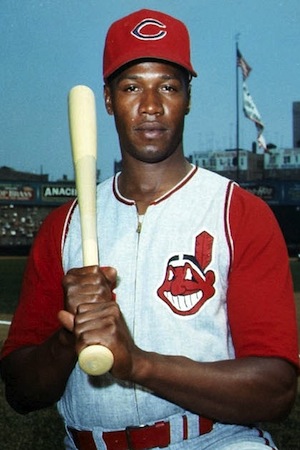

Chuck Hinton

In the foreword to Chuck Hinton’s autobiography, My Time at Bat, Sam Lacy said of Hinton, “He is a family man – one who does his baseball thing as a sideline.”1 Hinton’s devotion to family grew from the large and close-knit one into which he was born, but his life and that of his brothers revolved around sports from their earliest years. “We lived right behind a baseball field. Everybody played baseball,” Hinton wrote of his early years in North Carolina.2

In the foreword to Chuck Hinton’s autobiography, My Time at Bat, Sam Lacy said of Hinton, “He is a family man – one who does his baseball thing as a sideline.”1 Hinton’s devotion to family grew from the large and close-knit one into which he was born, but his life and that of his brothers revolved around sports from their earliest years. “We lived right behind a baseball field. Everybody played baseball,” Hinton wrote of his early years in North Carolina.2

Charles Edward Hinton Jr. was born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, on May 3, 1934. There were seven children, but the oldest son died as a toddler, leaving him the eldest surviving son. The oldest boy had natural advantages, but when Hinton reached an age when he wanted to focus his energy on baseball, especially in the summer, he was instead called on to tackle chores on his uncle’s tobacco farm.

His father owned and drove a taxicab that provided steady income, enough, Chuck said, to support a middle-class lifestyle with all the conveniences of the late 1940s and early 1950s: electric appliances including a television. Hinton recalled that many in the neighborhood did not have similar appliances; some did not even have indoor plumbing.

Rocky Mount was segregated completely, with railroad tracks dividing the white and black areas of town, but Hinton recalled lacking for nothing on his side of the tracks. There were ample recreational opportunities for a kid growing up, and though he was smaller than some of his peers, he became an athlete noted for his speed.

There was one impediment to Hinton’s growth as a baseball player. His high school, Booker T. Washington, had dropped baseball as a sport. Hinton played football at the school, but pursued baseball more seriously in American Legion ball. The 14-year-old was playing with youths considerably older, but he more than held his own.

From high school Hinton went on to Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, on a full baseball scholarship. He also played football and basketball for Shaw, joining a younger brother, James “Checo” Hinton, who was a lineman on the football team and a strong forward for the basketball team.

Checo Hinton was larger than Chuck and could hit a baseball a long way. But according to Chuck, his brother had no strike zone judgment, which limited his success as a player. By comparison, Chuck had remarkable patience at the plate and even from his early playing days could hit a curveball.

Confident of his skills, Hinton hitchhiked from Shaw University to major-league tryouts being held at Griffith Stadium in Washington in the summer of 1956. The initial group of more than 700 players was culled to 75 on the second day. Showcasing his speed — 60 yard in 6.5 seconds – and his ability to make consistent hard contact, Hinton was among those who made the grade.

Baltimore Orioles scout John “Pope” Whalen asked Hinton to come to Baltimore the next day for a further tryout, at which he signed Hinton to his first professional contract. For a $500 signing bonus and a promised monthly check of $200, Hinton began his professional baseball career as an Orioles farmhand.

Hinton was assigned to the Phoenix Suns of the Class C Arizona-New Mexico League as a backup catcher. When the first-string catcher was injured, he made the most of his chance, going 5-for-8 in his first two games as a starter. After the starting catcher returned, Hinton played the outfield. He batted .271 in 85 at-bats.

After his first success at professional baseball, Hinton was confident enough to elope with his high-school sweetheart, Irma Macklin, whom he always called Bunny. Shortly afterward Hinton was drafted by the Army. Assigned to Fort Benning, Georgia, played for the Special Forces baseball team; among his teammates was future major leaguer Deacon Jones.

Later reassigned to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Hinton played football as well as baseball. He maintained contact with the Orioles and attended batting practice sessions several times to keep his skills sharp.

Discharged from the Army, Hinton went to spring training with the Orioles in 1959. It was his first training camp and the first time that he saw players evaluated coldly and sent packing. In his biography, Hinton asserted that when white and black players of equal “or near equal” talents were in head-to-head competition, white players were given the preference. The remaining black players were of generally higher quality and got a chance to shine wherever they were assigned. Hinton believed throughout his life that most major-league teams had a cap on the number of blacks they would allow on the team, though he acknowledged notable exceptions like the Pittsburgh Pirates and Los Angeles Dodgers.3

For much of his early playing days, Hinton was a catcher. He emulated talented receivers like Josh Gibson and Roy Campanella. His desire to follow in their footsteps was thwarted when Oriole evaluators deemed him too athletic to be kept behind the plate. Sent to Aberdeen of the Class C Northern League (managed by Earl Weaver), Hinton was put in the outfield to take advantage of his speed and arm. Hinton had a breakout season; his.358 batting average led the league, and he was named the Rookie of the Year and the Most Valuable Player.

In 1960 the Orioles jumped Hinton to Vancouver of the Pacific Coast League, where he struggled and soon was demoted to Class C Stockton (California League), where he hit .369 for a second straight batting title, and hit 20 home runs for the second year in a row.

The Orioles added Hinton to their 40-man roster in time for him to be drafted by the expansion Washington Senators that offseason.

Because the Senators had yet to complete their farm system, Hinton played for Indianapolis, a Cincinnati farm team in the International League. He earned his first taste of the majors on May 13 when the Senators called him up.4 The Senators were still playing in old Griffith Stadium, and the team consisted largely of veteran players like Gene Woodling, Marty Keough, and Jim King, who were the starting outfielders. News accounts described the team as a collection of “veterans, rejects, and young hopefuls.”5

Hinton got his chance not only because he was hitting well but also because all of the veteran outfielders were left-handed hitters. The team needed a right-handed hitter and Hinton could play almost anywhere on the diamond. He joined Willie Tasby, the team’s only other African-American, who had come up through the Orioles system as well.

Describing hit first at-bat in the majors (a fly ball to center field), Hinton wrote, “I began to shake and quake.”6 It took him most of the first half of the game to get his excitement under control, but when he ran down a line drive near the wall in the middle innings, he finally felt himself. He hit into a double play in his second at-bat, but got singles the next two times up.

Hinton wrote in his autobiography that the biggest thrill of his first season came against the Yankees in Griffith Stadium on August 13. His mother and sister were there and he promised his mother that he would hit a home run for her. Batting leadoff for the Senators, Hinton hit a home run off Yankee pitcher Bud Daley.

Hinton hit .260 for the season with six home runs. Batting leadoff for much of the last three months, he had an on-base-percentage of .337 and led the team with 22 stolen bases. It was not the first time Hinton had played in the city. His sister Ellen had lived in the Washington area and as a youngster, Chuck often came to the city to visit as a teen. While there he sometimes played baseball on Washington semipro teams. When he returned as a player in 1961 it was the start of a lifelong relationship with the city, one Hinton called even from his early years a “second home.”7

Hinton also became an avid Washington Redskins fan. In 1962 he told a sportswriter that his secret desire was to play football for Washington as well as baseball. “I think I could make the club as a flanker and pass catcher, but I doubt the baseball team would give me permission,” he said.8 Hinton was probably correct because his 1962 season made him too valuable an asset to the Senators to risk on the gridiron. It was his best as a major leaguer. Manager Mickey Vernon did everything to keep Hinton’s bat in the lineup, playing him at all three outfield positions, second base and shortstop. Hinton hit for power (17 home runs) and average. He was in a tight race with the Red Sox’ Pete Runnels for the batting title in September, but fell off in the final weeks to .310, good enough for fourth in the American League. His 28 stolen bases were second to the White Sox’ Luis Aparicio, who led the league with 31. But the light-hitting Senators finished in last place.

The team rewarded its new star with a $20,000 contract for 1963. That season Don Lock and Jim King hit 27 and 24 home runs respectively, but the team as a whole scored even fewer runs than in 1962. Hinton spent most of the season hitting second, in front of the two sluggers. He was leading the team with a .280 batting average when he was hit behind the left ear by Ralph Terry of the Yankees at Yankee Stadium on September 5. He was out of action with a concussion for two weeks. He fell off to .269 at season’s end, though he continued as a premier base thief, second again with 25 steals to Luis Aparicio. The Senators finished last in the ten-team league.

Hinton wrote that he probably should not have played again after being beaned, but “I had to prove to myself I was not afraid of pitchers,” and so he played the final weeks. He said he saw double for most of the rest of the season and had long-term ringing in the ear.9

Hinton’s vision was restored to normal by spring training of 1964, and he started the season strong, playing for new manager Gil Hodges. He was selected to the All-Star team by fellow players, the first expansion Senator to be accorded the honor. He was a ninth-inning defensive replacement for Harmon Killebrew, and did not get an at-bat.

Hinton admired Willie Mays, and Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich called Hinton the “closest thing to an American League Willie Mays,” in the run-up to the All-Star Game. “He steals bases, charges groundballs, throws runners out, and also lugs the Senators’ biggest bat,” opined Povich.10

The Senators were concerned about Hinton’s health after the beaning late in 1963 and a knee injury he suffered in April of 1964. The first trade rumor to surface was that the Yankees would trade Roger Maris for Hinton. Trade talk accelerated during the offseason and concluded with Hinton going to Cleveland for first baseman Bob Chance and shortstop Woody Held. Povich wrote of the trade that it was Gil Hodges who wanted Hinton traded and that the trade talk affected Hinton’s play, noting that he was hitting .355 in June before falling off to .274 by the end of the year, still the best on the team.

Hinton’s 17 steals stood out on a team of slow, plodding players. But in Cleveland he was on a team with an accomplished batting order that featured outfielders Rocky Colavito, Leon Wagner, and Vic Davalillo. That left a utility role for Hinton. He filled in for Davilillo and played first, second, and third base as well. It was his first time playing for a winning team and he made major contributions to the team’s success. But both the Indians and Hinton were on a downward trend. Chuck spent six of his last seven seasons playing in Cleveland, but he never warmed to the situation as he had in Washington.

In his autobiography, Hinton complained about the cold in the city, about Municipal Stadium, which consistently drew the smallest crowds in the AL, and about his inability to beat the train crossing that made him miss flights. Gil Hodges would have had little sympathy on that last score and Hinton admitted that it made him obsessive about arriving on time for the rest of his life.

There was an in-between season with the Los Angeles Angels in 1968. Hinton said it was the worst year of his career, and by comparison it was. It was also the worst offensive year for many hitters as it was the Year of the Pitcher. Although Hinton hit only .195, embarrassingly below the Mendoza Line, the American League batting average overall was a scant .230.

Traded again after the 1968 season, Hinton was back with the Indians, where he finished his career in 1971. (He was released by the Indians after that season.) His career slash line of .264/.332/.412 for 11 seasons remained quite respectable for a player who perennially batted at the top of the order, and he was proud of reaching the 1,000-hit plateau.

Hinton found life after baseball very rewarding and said that the ability to get in more than just nine holes in a day, most players’ limit during the season, was reward enough. He was an avid golfer who as early as 1964 won the spring tournament between players and journalists.11 He said the best thing about the move to the Cleveland Indians was their spring-training complex in Arizona that allowed him to golf with Willie Mays. He said one of the biggest thrills of his life was playing 18 holes with Jackie Robinson.

After his release, Hinton was not completely done with baseball. He became the head baseball coach at Howard University in Washington, and held the post for 28 years. His teams won the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference championship six times. He had opened an insurance agency in Washington while a Senator, and he continued several small enterprises to supplement his income.

Golf opened another opportunity. After playing in the National Football League Golf Super Bowl in 1982, Hinton, playing in a promotional event with former Senators teammates Fred Valentine and Jim Hannan, proposed a similar event for baseball. Together with Brooks Robinson, they founded an organization that grew to number thousands of current and former players, umpires, coaches, and others, and sponsors golfing events to raise money for a wide variety of charities. The association was one of the proud achievements of Hinton’s life, but it did not rival the pride he had in his wife and four children.

Hinton died on January 27, 2013, and was buried in Quantico National Cemetery, Triangle, Virginia. His wife, three of his children and five grandchildren survived him.

Longtime broadcaster Phil Wood, whose history with baseball in Washington goes back to watching the Griffith Stadium Senators, said that along with Frank Howard, Chuck Hinton was one of the best position players from the Senators’ expansion years. As well, Hinton was his favorite guest to interview because he was “so real, so genuine.”12

Hinton was the first African-American player to star with the Washington Senators. He carved out a niche for himself in a city that had been slow to integrate its teams, and his success with Washington area fans called into question many of the assumptions about the city and its ability to adapt to the changing racial realities of the civil rights era.

When baseball returned to the city in 2005, Hinton was a frequent fan at RFK Stadium and later at Nationals Park. In the program for Hinton’s memorial service, Mark Lerner, principal owner of the new Washington Nationals, wrote of watching him play when he was a youngster. “Those are the memories I cherish most,” he remembered fondly.13 It was a fitting testament to Hinton’s role as a keeper of the flame who helped maintain the tradition of professional baseball in his adopted home.

Sources

Hinton, Chuck, My Time At Bat (Largo, Maryland: Christian Living Books, 2002).

Addie, Bob, “28 Orphans Adopted,” Washington Post, December 15, 1960.

Addie, Bob, “Nats Recall Hinton, Stadium Deal Ready,” Washington Post, May 14, 1961.

Addie Bob, “New Nats Begin New Era Today,” Washington Post, April 10, 1961.

Addie, Bob, “Hinton’s Secret Desire to Play for Redskins,” Washington Post, September 11, 1962.

Povich, Shirley, “This Morning,” Washington Post, August 23, 1962, June 9, 1964.

Notes

1 Chuck Hinton, My Time at Bat (Largo, Maryland: Christian Living Books, 2002),. i.

2 Hinton, 8.

3 Hinton,. 89.

4 Bob Addie, “Nats Recall Hinton, Stadium Deal Ready,” Washington Post, May 14, 1961, C1.

5 Bob Addie, “New Nats Begin New Era Today,” Washington Post, April 10, 1961, A13.

6 Hinton, 46.

7 Hinton, 10

8 Bob Addie, “Hinton’s Secret Desire: To Play for Redskins,” Washington Post, September 11, 1962, A15.

9 Hinton, 58.

10 Shirley Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, June 9, 1964, A23.

11 Washington Post, March 14, 1964, C4.

12 Hinton, 41.

13 Mark Lerner, “Remembering the Legacy,” Chuck Hinton Memorial Service Program, February 12, 2013.

Full Name

Charles Edward Hinton

Born

May 3, 1934 at Rocky Mount, NC (USA)

Died

January 27, 2013 at Washington, DC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.