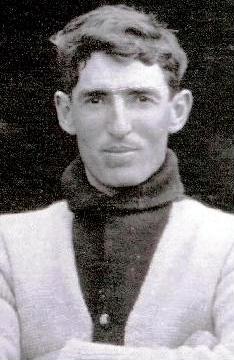

Clare Patterson

In a brief trial with the 1909 Cincinnati Reds, Clare Patterson compiled the entirety of his major league record: four games, eight at-bats, one hit, one RBI, four put-outs. A quick washout—or so it would seem. In truth, Major League Baseball did not finish its evaluation of the outfielder’s talents. Patterson would later earn a second big league chance, but it was a chance denied when his career came to an abrupt and ultimately tragic end.

In a brief trial with the 1909 Cincinnati Reds, Clare Patterson compiled the entirety of his major league record: four games, eight at-bats, one hit, one RBI, four put-outs. A quick washout—or so it would seem. In truth, Major League Baseball did not finish its evaluation of the outfielder’s talents. Patterson would later earn a second big league chance, but it was a chance denied when his career came to an abrupt and ultimately tragic end.

Whether Patterson was capable of competing at the highest level will forever remain an open question. He was, however, a player who flashed promise in his 455-game minor league career. Two of his four seasons were shortened by illness and a third, by suspension. Yet, he had a picture-perfect year with the Guthrie Senators in 1909, when he led the Western Association in hitting with a .354 average and 180 base hits. And, he had what might have been a breakthrough year in 1912, when he transformed himself from a utility outfielder into one of the Pacific Coast League’s hottest prospects.

During the final few weeks of the 1912 season, he should have been on the field, helping the Oakland Oaks secure the team’s first PCL championship. Instead, Clare Patterson found himself fighting for his life. It was a fight that would end in a tent in Mojave, California, a distant 1200 miles from his home in south central Kansas.

Patterson’s roots were anchored in a place called Rainbow Bend. Not a town, the name referred to a rural neighborhood in Cowley County, Kansas, with a distinctive geographic feature—a bold, almost majestic meander taken by the Arkansas River on its way south toward Oklahoma. Samuel and Harriet (Hattie) Patterson, Clare’s parents, migrated to the area from Illinois in 1880 to settle on a farm near Sam’s mother and brothers. Their farm was located less than ten miles from the county’s two largest population centers, Winfield to the northeast and Arkansas City to the southeast. Lorenzo Clare, the couple’s fourth eldest child, was born several years after their arrival in Kansas, on October 5, 1887. Baseball sources typically identify Arkansas City as his place of birth, but it is more likely that Clare was born at his parents’ farmstead.[1]

While Clare was still a young child, a succession of sorrows befell the Patterson family. Hattie bore five more children after him, including two sets of twins. Of those births, only one child survived past the age of two. Then, in a blow especially devastating to a small boy, Clare lost his father. Early in 1895, Samuel Patterson suffered a breakdown that placed him in the Kansas State Insane Asylum in Osawatomie. He died at the hospital less than two years later, in December 1896. Clare was only nine years old.

Hattie not only kept the family together, she managed to keep the farm going, using its 160 acres to produce wheat, corn, and hogs. The Pattersons had struggled to maintain an even keel financially before Sam’s illness, and the years following his loss were no less challenging. The five children—three boys and two girls—almost certainly were introduced to hard work and responsibility at a young age. Nonetheless, education was important, and they attended Rainbow Bend’s country school, District #61, located a half-mile from the Patterson farm.

Athletic ability was not the earliest of the interesting qualities to emerge about Clare Patterson. At the age of 16, he became a correspondent for the Winfield Courier, a leading Cowley County newspaper that published both daily and weekly editions. Clare was one of many columnists who reported on news from the rural parts of the county. Correspondent columns were not signed, but it’s believed that Patterson penned nearly 60 between 1904 and 1908.[2] The editorial preference called for columns that hewed to a simple presentation of facts—concise, objective, unembellished. Most columns conformed, but Patterson’s often did not, displaying instead a distinctive style and voice.

Clare used the Rainbow Bend columns not only as a venue for reporting local goings-on, but also as a forum for creative expression. Sometimes he wrote in verse. Sometimes he wove a tale from a small bit of news. On a couple of occasions, he issued back-off salvos in personal disputes with unnamed parties. The columns are short on polish, but they reveal a young man who had an imaginative mind and who was engaged in his community. Most of all, they reveal a quirky wit. He loved plays on words, even corny ones, and he saw a light, offbeat side to the most mundane of events. The sense of humor so evident in the Rainbow Bend columns later became a trademark feature of his baseball persona. (See the appendix for examples of the creative aspects of Patterson’s writing in the Rainbow Bend columns.)

Another surprising achievement dates to this period. Two pieces of sheet music copyrighted in 1905 credit Clare Patterson as being the lyricist. One of the songs, Some Pretty Little Girl Is Looking for Me, is light, whimsical, and similar in style to some of the verses that appear in the Rainbow Bend columns. The other, You Have a Mother at Home Boys, has a much darker theme, telling of a soldier dying on the battlefield. Both songs were published by the same small Chicago company, but the melodies were written by different composers. The music has been passed down through the family and survives. Unfortunately, so does a mystery. No one knows how this farm boy from Kansas found his way into the music publishing world in the early 1900s. (See the appendix for the lyrics of both songs.)

In the spring of 1905, the Kansas State Census identified Patterson as a farmer. In the fall of that year, he decided to continue his education by enrolling at St. John’s College, a small Lutheran school in nearby Winfield. Clare apparently was not taking college-level coursework, but he was listed among the Second Preparatory class in the Classical and Scientific Departments. He also was included in the Initiatory class in the Phonographic Department, which offered courses in office skills such as stenography, typewriting, filing, and related subjects. His plans for applying these skills remain unknown.

During the one academic year that Clare attended St. John’s, he was a member of the college’s basketball and baseball teams. In basketball, he played both guard and center. St. John’s had no gymnasium of its own, but the school garnered city championship laurels in the winter of 1905-06. The basketball team finished with an 8-1 record against the three other teams in the league, all from Winfield: Southwestern College, Winfield High School, and the YMCA.

With the arrival of the 1906 college baseball season, Patterson started to attract attention. In early May, the Winfield Daily Courier tagged him “…a comer….[who] knows the game and plays it.”[3] At this stage of his development, he was primarily a pitcher, but he also played the bases and the outfield. The St. John’s team faced both local opponents and teams from nearby towns, its principal rival being Southwestern, Winfield’s other college team.

Patterson—who threw right-handed and batted left-handed—received favorable newspaper mention on several occasions, but perhaps his most memorable college game was his final one, in which he led St. John’s to a 11-8 win over Southwestern. From the mound, he allowed seven hits and registered 14 strikeouts. The pitching performance was decent enough, but he made the day special with his bat by hitting for the cycle, including a three-run home run. The victory gave St. John’s a 2-1 edge in its games against Southwestern that spring, and claim to the city title.

For the next couple of summers, Clare played amateur and semi-pro ball with various teams in southern Kansas and northern Oklahoma. Most likely, he also continued to help his older brothers Chancey and Elwood with the farm during this time. His thoughts about a career, however, drifted away from farming. He would pursue baseball as far as it would take him. Beyond that, he expressed interest in trades such as painting, plastering, carpentry, and blacksmithing.

In the spring of 1908, Clare had his first exposure to the minor leagues.[4] The Wichita Jobbers, of the Class C Western Association, invited him to their March workouts and tested him for the outfield, which would eventually become his primary position. The Jobbers culled him early—just over a week into the tryout, the Wichita Eagle reported on the team’s intention to send him to the Tulsa Oilers of the Class D Oklahoma-Kansas League.

The Tulsa plan fell through, but Patterson still headed to Oklahoma to play ball in April 1908. He joined the Ponca City Boosters, an independent town team, as its starting first baseman. The Boosters fielded a strong nine, and he quickly established himself as one of the team’s most reliable hitters. Through his first 36 games with the Boosters, Patterson recorded a .286 average, which was among the team leaders.[5]

By mid-July, the Boosters began having trouble lining up games, presumably because many of the lesser teams in the area had lost interest in taking them on. After losing a challenge series to Blackwell, Oklahoma, at the end of July, the Boosters disbanded.

The Ponca City players quickly affiliated with other teams. Winfield reportedly had an interest in signing Patterson, but he ended up with the Arkansas City Grays and soon became a fan favorite. He was a power at the plate, speedy on the bases, and versatile in the field. He could, it seemed, perform well wherever he was needed, whether at first or third base, in the outfield, or on the mound in relief. The Arkansas City Daily Traveler liked the whole package, calling him “…one of the cleanest, fastest and nicest ball players ever on our grounds….cool and even tempered.…”[6] Moreover, the Traveler reported, he sported “the smile that won’t come off.”

Patterson’s work in 1908 led to renewed minor league interest in the spring of 1909. He was invited to train with the Springfield (Missouri) Midgets of the Western Association and was optimistic about his chances for joining the team as an outfielder. Springfield released him, however, and for a time it looked as if he might return to Arkansas City, which had obtained its first minor league franchise since 1887. Then, the Guthrie Senators entered the picture with an offer, and Patterson snapped it up.

The Senators, a Class C Western Association team based in Guthrie, Oklahoma, soon realized that they had scored in signing Patterson. Before league play even commenced, Howard Price, the team’s manager, refused an enticing offer from the Oklahoma City Indians, a Texas League team. Oklahoma City was willing to give up either of its two best pitchers, or an infielder, in exchange for Patterson. Manager Price rebuffed not only this deal, but any idea of a cash consideration.

Opening day of the 1909 season was April 30 in Guthrie, and the inaugural game against Muskogee was cause for community-wide celebration. The governor and the mayor formed the battery for the ceremonial first pitch. The stores closed early so the town’s retailers could join in the parade from city hall to the ballpark. A “vast crowd” of 6,000-8,000 filled the stadium. Western Union opened a branch office in the grandstand to make it easier to send game updates to other Association towns.

Patterson started the game in right field and asserted himself immediately. He began his season and minor league career with a 3-for-4 day, helping Guthrie win the opener, 8 to 6. From there, he took his auspicious start on a season-long spin. In his first three games, Clare went seven-for-twelve, including two home runs. In his first 26 games, his average surpassed .350.

Patterson’s strength was his hitting, but he had another asset in his speed. Clare was unusually fast given his 6’0”, 180-pound build, and it was an advantage which he applied effectively on the bases and in the field. He could make a spectacular running catch, he could steal a base, and he could lay down a fine bunt and beat it out.

By early June, Clare was the sensation of the league—and the subject of growing speculation. An early report, apparently unfounded, said that the Washington Senators wanted to acquire him and farm him out to Minneapolis. The rumor mill barely had time to warm up, however. Louis Heilbroner, whom Sporting Life described as “the most famous and active of all base ball scouts,”[7] came to Guthrie to watch Patterson work, then recommended him to his employer, the Cincinnati Reds. On June 24, 1909, Guthrie announced that it had sold Patterson to the Reds, and that he would join the big league club at the conclusion of the Western Association season.

Shortly after the sale to Cincinnati was announced, Patterson switched from playing primarily in right field to center field. His usual spot in the batting order also shifted from third to leadoff. He continued to dazzle. During a 15-game stretch in July, he hit .406. In early August, his season average stood at .376, and he led the league in stolen bases. His consistent productivity at the plate was punctuated with standout moments. On August 16, in a game against Sapulpa, Patterson drove the ball into deep center and sped around the bases for an inside-the-park home run. A week later, he put on a particularly impressive display in consecutive games against the league teams from Pittsburg, Kansas, and Springfield, Missouri. In those two games, Patterson went 10-for-11, and touched a total of 18 bases.

On September 1, Clare played in his last game for Guthrie, a three-inning appearance against Springfield. He left the game early to catch the train for Cincinnati, but not before delivering a run-producing double as a parting gift to the hometown fans.[8] At season’s end, Patterson’s record with the Senators stood at 120 games, 180 hits in 509 at-bats, 98 runs, and a .354 batting average. He led the Western Association in both hits and batting average, outpacing the second-place finishers by 37 hits and 17 points, respectively. Clare also stole 44 bases, good enough to finish in a tie for fourth place.

The rocket ride in Guthrie slowed to a more pedestrian pace in Cincinnati. In the month that Patterson spent with the Reds, most of the team’s evaluation of him presumably occurred on the practice field. He broke into the lineup only four times, all but one of them in games against the St. Louis Cardinals. The first two opportunities were spaced nearly a month apart, and lasted only minutes. Both were bottom-of-the-ninth pinch-hitting assignments as a replacement for the pitcher. Then, on October 3, manager Clark Griffith penciled in Patterson as the Reds’ starting left fielder in a home game against St. Louis. He had two putouts in the six-inning game and made no errors, but he had no success at the plate. Clare’s last game for the Reds occurred on October 5, his birthday, when he again started in left field. The game was the final one of the season, it was essentially meaningless, and it was called after seven innings because of darkness. Still, it was the game in which he made his only major league hit, a single. The game probably carried additional interest to Patterson because it featured his famous Cowley County neighbor, future Hall of Famer Fred Clarke, and Clarke’s soon-to-be 1909 world champions, the Pittsburgh Pirates. Patterson and Clarke were acquainted—Clare cited Clarke as a baseball mentor—but the extent of their relationship is not known.[9]

Just days after he returned home from Cincinnati, Clare surprised some of his friends by getting married. On October 14, 1909, Patterson wed Ferol Genevieve Heath, a nineteen-year-old print shop compositor from Arkansas City. According to the Daily Traveler’s front-page story about the wedding, Ferol was “one of the city’s most popular young ladies.”

The newlyweds had barely settled into married life when news arrived that Cincinnati would likely send Patterson to the Fort Wayne Billikens of the Class B Central League. Reports of his impending demotion circulated in early November; the official announcement came on November 24. Louie Heilbroner, who had originally scouted Patterson, brokered the deal with Fort Wayne. The transaction involved a total of four Reds players “not found quite heavy enough” to remain with the big league club.

Patterson was not dissuaded; if anything, he still had a large store of residual confidence from his success in Guthrie. When Fort Wayne sent him a contract early in 1910, Patterson initially returned it unsigned. He wanted to sweeten the deal by making a series of monthly $50 bets with owner Claude Varnell that he could hit .300 or better in each month of the season. Fortunately for Patterson, Varnell did not seriously entertain the proposal, and the team’s management persuaded him to sign the original contract.

Unlike the smooth sailing in Guthrie, the going in Fort Wayne was rocky from the start. Only a few days into spring practice, Patterson suffered a leg injury that affected his training and possibly, his early season performance. There also was hint of an arm problem before the start of league play. Whatever the reasons, Patterson began the 1910 season in lackluster fashion, especially when measured against high expectations. In the latter half of May, he finally appeared to be rounding into form. His batting average was steadily improving, as was his fielding. However, in mid-June, Clare regressed into “an awful batting slump” that prompted the manager, Jimmy Burke, to bench him briefly. Just as he was beginning to show signs of breaking free from the latest setback, the wheels fell off altogether.

After the first game of a doubleheader in Dayton on July 4, Patterson and his manager had a nasty verbal row that resulted in Patterson’s dismissal from the team. Burke was understandably upset when a pop fly dropped into play because neither Patterson, in left field, nor Edward Justice, at short, called the other one off to field it. When Burke tried to coach Clare about the error, he got a surly response, and the situation deteriorated from there. The suspension was immediate, and it opened the door to a litany of criticisms in the press about Patterson’s shortcomings. Burke fumed about his “slovenly play” and indifferent attitude about the team’s success.[10] The Fort Wayne Sentinel considered his “great fault” to be that he could not learn “inside base ball.”[11] He could not, the Sentinel continued, “remember a signal from one day to another,” which “balled up a lot of plays.” The Sporting Life explained that his suspension “…followed a succession of bone-headed plays that …. cost the locals [Billikens] several games.”[12]

In Arkansas City, the Daily Traveler suggested another possibility, that Burke “had it in” for Patterson and was looking for an excuse to get him off the team. Even in Fort Wayne, a line of reasoning would later develop that Burke and Patterson had just not been compatible. According to the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, many of the locals came to believe that Burke had mishandled Patterson, that the young outfielder did not respond well to Burke’s impatient “naggings” and other managerial tactics, and that he lost heart and motivation as a result.[13]

Despite the sour relations with Burke and struggles on the field, Patterson was an important member of the Fort Wayne team at the time of his departure. He had raised his batting average to .280, and was considered one of the best hitters on the team. The Billikens were contending at the time, trailing the league-leading South Bend Bronchos by only two games. That they eventually finished 8.5 games behind South Bend was later attributed, in part, to the team’s difficulty in finding a suitable replacement for Patterson in left field.

Patterson’s forced time-out ended in the latter part of August 1910, when he was sold to the Class D Central Association team in Quincy, Illinois. Clare played 29 games with the Quincy Vets, and helped the team clinch the league championship with his .411 batting average during the final weeks of the season. The stopover in Quincy was a brief one, though. In the offseason, the hot-stove reports told of his return to the Fort Wayne roster, and as the 1911 season approached, it became clear that expectations were once again beginning to build. The mood in Fort Wayne toward Patterson was now upbeat, optimistic, and welcoming—especially since a potential trouble spot had disappeared when Jimmy Burke accepted the managerial position in Indianapolis.

The Fort Wayne hoodoo still lurked, however. This time, Patterson was taken out of action early in spring training because of appendicitis. His surgery on April 8, 1911, was followed by several weeks of recuperation, first in Fort Wayne, then in Arkansas City. By the time he was ready to return to the field, Fort Wayne had long since filled its roster and had no room for him. In June and July, Clare moved in fairly rapid order from Quincy, Illinois, then in the Class B Three-I League, to Kewanee, Illinois, and Burlington, Iowa, both of the Class D Central Association.

The lingering effects of Patterson’s illness, plus the fact that he had missed spring training, were evident in Quincy, where he batted only .183 in 25 games. In the Central Association, he benefited from both his growing strength and the lower level of competition. He hit for a combined average of .343 in the 50 games he played while in Kewanee and Burlington. Clare also earned a $50 bonus when, on July 23 in Burlington, he slugged a home run that ricocheted off the park’s Bull Durham advertising sign. With that feat, he became one of 238 players nationwide to cash in on the tobacco company’s promotion that season.

Scouts for the Oakland Oaks must have been scouring the Midwest, for in August 1911 the Class A team purchased Patterson from Burlington for $1250. The Oaks were in the market for an outfielder because Harl Maggert, the team’s star left fielder, was slated to join the Philadelphia Athletics after the Pacific Coast League season. Maggert, however, was a disciplinary handful who was inclined to test limits. Just before Patterson’s arrival in Oakland, yet another of Maggert’s behavioral flare-ups prompted Harry Wolverton, the Oaks’ manager, to suspend him for insubordination. It was Maggert’s third suspension of the year, and it proved to be his final release from the team.

Maggert’s early exit created an opening, but Patterson did not immediately make the Oaks’ starting lineup. When he reported to the team, he found that Bert Coy had been promoted from the Oaks bench to join regulars Elmer Zacher and Izzy Hoffman in the outfield. Hoffman, however, soon faced disciplinary problems of his own. In a game against Portland in early September, Izzy was ruled out in a close play at first base. His aggressive demeanor toward the umpire following the call resulted in a league suspension that lasted over a week. The controversial penalty gave Patterson his first sustained opportunity in the Oaks’ starting lineup.

Clare’s nine starts in the outfield during Hoffman’s absence included two highlight games in Los Angeles, when he went 3-for-5 and 4-for-6 at the plate. After Hoffman’s suspension was lifted, Izzy reclaimed his position and Patterson returned to the bench. Shortly thereafter, however, Clare became a starter in center field. The move occurred not because Patterson had bested any of his outfield rivals, but because Wolverton, the manager, opted to transfer Elmer Zacher to first base, a weak spot in the defense that needed shoring up.

As September rolled into October, Patterson had reason to feel good about his progress with the team. He also had a more personal cause for celebration as well. On October 5, his birthday, Ferol gave birth to the couple’s daughter, Loraine Maree, in Arkansas City. Two days later, however, the momentum that had been building stalled out. His season ended abruptly because of a knee injury sustained when he was spiked sliding into a base.[14]

By the end of the 1911 season, Patterson had begun to acquire a reputation as “comedian of the league.” The team itself inadvertently provided him with a stage by assigning him sideline coaching duties. According to The Sporting News, his sideline antics sometimes resembled “certain Salome dancers.” Throughout the remainder of Clare’s association with the Oaks, numerous newspaper references would be made to his fondness for humor. The Oregonian dubbed him a “high-cheeked clown” when he used his arms as oars after sliding into a very muddy puddle near second base. The paper also considered him one of a handful of comedians in the league who reveled in “…a little of the funmaking stuff [that] helps to keep up interest in baseball.” The local paper, the Oakland Tribune, referred to him as “our elongated funny friend,” the “jolly fielder,” and a “lovable humorist.” [15]

Although Patterson gained a measure of acceptance with the Oaks in 1911, his batting average had reached only .252, and he had not proven himself to the point that he had secured a spot in the starting lineup. During the offseason, he was viewed as “one of the best outfield prospects in the league” or, alternately, as a second-tier, utility player in a “hummer of an outfield.” Harry Wolverton, the man who made Patterson an Oak, gave him a strong endorsement. Wolverton noted that Clare had come to Oakland after a “siege of sickness,” still 20 pounds under his normal weight. He forecast that Patterson was primed to “surprise the natives” in 1912.[16]

Wolverton, however, would not be there to see it. He left Oakland in the offseason to become the manager of the New York Highlanders (later Yankees). His replacement was Bud Sharpe, an accomplished first baseman who had played most recently with the Buffalo Bisons and before that, with the Boston Doves. As a player-manager, Sharpe’s selection presumably addressed the Oaks’ problem at first base, thus solidifying Hoffman, Zacher, and Coy as the likely starters in the Oaks outfield. And, indeed, that is how the season started. For the first three months of the 1912 season, Patterson was a bench player, used primarily as a substitute for the starters. Still, the need to substitute arose fairly often—through July 2 he had played in 48 of the Oaks’ 83 games.

Once again, Patterson would benefit from Izzy Hoffman’s misfortune. Hoffman, who had batted .286 for the Oaks in 1911, had a decidedly off year in 1912. As of June 9, Hoffman’s average was only .238 (although he would eventually raise it to .255). Hoffman’s struggle translated into Patterson’s opportunity. In late June-early July, Patterson became an everyday player for the Oaks, and he excelled. As his at-bats increased, so did his average—progressing from .267 on July 2, to .282 on July 28, to .307 on August 27.

By mid-September, the planets seemed to have aligned in Patterson’s favor. His .345 average during the preceding month suggested that he had once again found the groove that had served him so well in Guthrie. He had earned a starting position in what many considered to be the Pacific Coast League’s best outfield, and had proven his mettle at the highest minor league level.[17] The Oaks had just taken over first place in the PCL standings, establishing that the team was a serious contender for the pennant. And, on draft day, September 16, Patterson was identified—along with catcher Carl Mitze and second baseman Bill Leard—as one of the Oaks whom major league teams wanted to draft.

Three Oaks were on the draft list, but National Baseball Commission rules specified that only one player could be drafted from each Class AA or Class A minor league club. Patterson was selected as the lone draftee from the Oaks when his name was literally pulled out of a hat in the commission’s Cincinnati office. Four teams wanted him—the St. Louis Browns, the Chicago White Sox, the Boston Braves, and the New York Giants. The Browns won the right to draft him following a two-step raffle procedure similar to the one used to select Patterson over the other Oak players.[18]

Eleven days after the draft, on September 27, 1912, the Oaks played the Sacramento Sacts and beat them, 7 to 3. Patterson started in left field, batted second, went 1-for-3, and scored a run. It was the last time he appeared in a box score.

Clare had started to feel ill, seemingly with a cold, sometime during the latter part of September. He traveled with the team to Portland, but did not attempt to play during the series with the Beavers. On October 5, his condition suddenly worsened, and he was taken on a stretcher to Portland’s Good Samaritan Hospital.

The first news report indicated that doctors were uncertain as to whether Patterson’s illness was pneumonia or typhoid fever. During the days that followed, his condition was most often reported as pneumonia or congestion of the lungs. Clare remained hospitalized in Portland until October 13, when he returned to Oakland to convalesce.

For the next two weeks, the Oaks, without Clare, battled with the Vernon Tigers in a hotly contested PCL pennant race. Oakland finally clinched the championship on October 27, the last day of the season. On several occasions during the stretch drive, the Oakland Tribune lamented Patterson’s absence from the team. He was, according to the paper, “the team’s best hitter,” “one of the finds of the season,” a “prime favorite” among the fans, and “one of the most valuable of all ball players….whose hitting, base running and fielding have been sadly missed….”. The Sporting News also noted his loss, calling him “the most dangerous hitter on the team.” At season’s end, Patterson led the Oaks in hitting. In his 138 games, he had registered 157 hits in 515 at-bats, for an average of .305. He had also tallied a respectable 30 stolen bases.

In late October or November, Clare relocated to Mojave, California, in hopes that the dry desert climate would hasten his recovery. John Tiedemann, an Oaks teammate, visited him there in late November, and found Clare to be “looking like his old self again.” The assessment was, at best, wishful thinking.

In mid-January 1913 it started to become clear just how dire Patterson’s situation was. When the St. Louis Browns sent Patterson his contract, Clare’s wife Ferol wrote to George Stovall, the Browns’ manager, telling him that Clare was too ill to sign it. Stovall was in Southern California and traveled to Mojave to see Patterson’s condition for himself. The visit convinced Stovall that Patterson would never again play baseball. He was touched by Clare’s plight, and immediately upon his return to Los Angeles, he began a collection among Southern California players to provide financial aid for the Pattersons.

The news account of Stovall’s visit was among the first of many that would sketch out a bleak, heartrending scenario. Patterson was “camping out” in Mojave, living in a small tent, attended by his mother, wife, and small daughter. He was a “mighty sick man” who had lost much of his weight and who, for weeks, had barely been able to sit up. He was waging a brave and gallant fight that he was not expected to win. His illness had drained the family finances.

In odd juxtaposition to the events unfolding in Mojave, a series of correspondence about Patterson was being exchanged at rather high levels.[19] Early in 1913, Claude Varnell, owner of the Fort Wayne team, wrote to August (Garry) Herrmann, Chairman of the National Baseball Commission, to file a claim against Patterson. Varnell was seeking repayment of $20 that he had loaned Clare to travel from Fort Wayne to Arkansas City following his surgery for appendicitis in 1911. Others involved in the correspondence included Ban Johnson and Thomas Lynch, presidents of the American League and National League, respectively. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of these letters—which were obviously written without knowledge of the severity of Clare’s illness—was Ban Johnson’s view on his major league prospects. Johnson wrote that it was “highly improbable” that the St. Louis club would retain Patterson following spring training, although he did not elaborate on his reasons for thinking so. Once the news from Mojave began to circulate, Varnell immediately withdrew his claim.

In February 1913, various news reports began to explicitly acknowledge what Patterson had probably known for some time—that he suffered from tuberculosis.[20] The diagnosis may provide an explanation for the family’s use of a tent for housing. Tent cottages were sometimes used in the treatment of TB patients to maximize their exposure to fresh air. It does not seem likely, however, that Clare was in a formalized treatment setting. Mojave was a small town and had no known tuberculosis treatment facilities. Moreover, it is clear that Clare’s illness left the family destitute, suggesting that his access to medical care was increasingly limited as the disease progressed.[21]

John Tiedemann of the Oaks paid a second visit to Clare in mid-February, and returned to Oakland with a call to action. Something, he reported, had to be done “at once” to help the Pattersons financially. The Oakland Tribune suggested a benefit game, and plans were immediately set into motion. The Tribune recognized, however, that “probably it is too late.”

The Patterson benefit game was played on February 23 and featured the Oaks versus the Lowenburg All-Stars (or Wielands). The Oaks fielded a blend of newcomers and veterans, including several of Clare’s former teammates—Carl Mitze, Gus Hetling, Bert Coy, John Tiedemann, Bill Leard, and Cy Parkin. The weather threatened to be uncooperative, but an estimated 2,000 fans still turned out to give their support. Among them was White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. The “Old Roman” refused a complimentary ticket and instead paid $20 to sit in a 25-cent bleacher seat. The Oaks lost the game 6 to 5 in the tenth inning, but on that day, the score was not the outcome that mattered. When the gate receipts from the benefit game were added to direct donations, the Oaks had collected $935 for Clare and his family.[22]

On March 21, Clare wrote a note to the secretary of the Oaks to thank the club for its efforts on his behalf, as well as the many individuals and organizations who had contributed to the benefit fund. It was a message that spoke not only of gratitude, but of hope. A week later, on March 28, 1913, Clare Patterson died. He was 25 years old. Ferol and Loraine Maree accompanied his body home to Arkansas City and buried him there, in Riverview Cemetery, on April 1.

The Oaks lowered the flag to half-mast at their new ballpark in Emeryville. The St. Louis Browns made their final preparations to embark on a dismal season. The papers first mourned Patterson’s passing, then wondered if the Oaks would have to return the $2,500 they received from St. Louis when Patterson was drafted.[23] Clare’s mother, Hattie, stayed in California, unable to bear the sight of burying another child.

Among the family keepsakes from Patterson’s life is a haunting photograph made sometime during those final months in Mojave. The camera captured a quiet moment, yet a foreboding one. The setting is outdoors, near the entrance to a small structure. Clare is in the foreground, resting semi-reclined and bundled in blankets, his face gaunt but handsome still. Standing a few feet behind him is Ferol, holding Loraine Maree. Years later, the photo still evokes a sense of dreaded, impending loss—a powerful image made even more so by the youth of its subjects.

Among the family keepsakes from Patterson’s life is a haunting photograph made sometime during those final months in Mojave. The camera captured a quiet moment, yet a foreboding one. The setting is outdoors, near the entrance to a small structure. Clare is in the foreground, resting semi-reclined and bundled in blankets, his face gaunt but handsome still. Standing a few feet behind him is Ferol, holding Loraine Maree. Years later, the photo still evokes a sense of dreaded, impending loss—a powerful image made even more so by the youth of its subjects.

The sorrows felt in the spring of 1913 are long since gone. The baseball feats, both accomplished and unrealized, are even further removed in significance. Yet there is something about Clare Patterson, something about his nearly-forgotten story that takes us back, draws us in, and makes us wish for a different ending.

Photo Credits

Genny Kenslow

Appendix — Excerpts from Rainbow Bend Columns

One bright, and cool November day,

Mr. Douthitt, so the neighbors say

Shouldered his gun and started away

Silas Thurlow’s beef to slay.

The sun in the air o’ higher rose

How high perhaps no one yet knows,

Mr. Thurlow around about with excitement flew

And as time rushed on excitement grew.

At last preparations all complete

They started to accomplish the killing feat

But the animal being wild and spry

It would not allow them to come nigh.

They soon decided that they must plan

To kill the critter as it ran

So with a consultation of a minute or more

They changed their tactics other than before.

They drove the small herd up beside the barn

While Mr. Douthitt stood around the corner with the death iron

They decided that the best time to shoot would be

The moment that he the beef’s head did see.

So Mr. Douthitt stood with waiting aim

Ready to shoot the beefy game

As the opportune of killing nearer came

He became more anxious to not miss his aim.

He waited and watched for the forehead spot

And when he saw it of course he shot

Then Mr. Thurlow yelled Pum I did not allow

To have you kill my best milch cow.

—From “Rainbow Bend,” Winfield Courier, November 23, 1905, p. 12.

Would you wear a diamond? The other day Mr. Mert Patterson came out of his house and went slowly down to the barn glancing down across the pasture, he saw something glittering. He could not think what it could be, so he walked down that way, upon arriving there he found it to be a real diamond. After looking at it for a long time he returned to the house and broke the news to his wife that he had found a nice large diamond. O what luck, replied she, what kind was it red or white? Neither replied he. Well what kind was it then. I’d like to wear it to church. Oh, its only that base ball diamond that the country boys used to play ball on, but you may wear it if you like.

—From “Rainbow Bend,” Winfield Courier, December 29, 1904, p.6.

Clare Patterson went to Ponca City this week to play ball. He hopes to be fast enough to get in the gate before it is closed.

—From “Rainbow Bend,” Winfield Courier, April 16, 1908, p.5.

Mr. Will Brodhearst was in this neighborhood last Saturday with his auto. You auto seen the time he had passing the players of All a Mistake on his way to Oxford. He says they made a mistake, they auto have turned off on a cross road so he could pass but they didn’t. The Misses Beeks horse very nearly got away. It was said that after the excitement was over Miss Claudia Beeks did get away making more dust than the auto. We don’t see why she auto have done it.….. The play All a Mistake will be played at the Rainbow Bend school house Saturday night, March 21. Admission, 10 and 20 cents. This play was given at Oxford last Saturday to a fifteen dollar house.

—From “Rainbow Bend,” Winfield Courier, March 19, 1908, p. 1.

It is certainly hard to go through life

Without having a little strife.

For some people you know,

Are trying to run others business just so,

This they are unable to do by far,

Not half as able as they think they are.

But I hope they will soon see

That they are not as competent as they should be

To run my business for me.

But when death my living has defied

And at last I have died

I will be satisfied—

To have you decide—

To run it then.

But as long as I live, I’d have you know

That I’ll run my business as I go

And if you do not attend to your own

Among your friends you’ll soon be known—

If anyone this should hit

Please do not on your high horse get.

—From “Rainbow Bend,” Winfield Courier, November 17, 1904, p. 12.

Away off in the distant horizon I could see a small object drawing near it was a very small hardly visible by the naked eye, yet on its way it met a person, and stopped, but soon passed on, but in the few moments it had stopped it had grown by half. It came on a little faster, now that it had grown, but it had not advanced far when it met another person. Of course it stopped, but soon passed on and my! how it had grown. Now it could and did travel at a rapid rate. It soon met another person and another and another, still growing all the while, and the larger it grew the faster it went. Now, what do you suppose it was, but the always traveling gossip of the world.

—From “Rainbow Bend,” Winfield Courier, August 18, 1904, p.1.

(The following poem was explicitly attributed to Patterson and was published before he took over as correspondent.)

Of all the states out in the West,

The one called Kansas no doubt is best,

It’s broad prairie lands are beautiful to see,

And just the thing for you or me.

One great mystery I will have to tell

Is how the people get land to sell,

It is easy got, I will admit,

With the privilege of inspecting all you get.

So now just for a little fun,

I will tell you how this is done.

At first the rain forgets to call,

Till finally it does not come at all.

So when the ground gets good and dry,

And all clouds disappear from the sky,

A little breeze will begin to circulate,

To inspect the condition of the state.

But on the journey it takes a fright,

And changes the day into night,

For real estate begins to rise

Far up into the glistening skys.

Everybody concludes to trade land,

So they exchange dirt for sand.

And if you poke your head out of the door,

The hurricane will yell, here is plenty more.

So after the excitement is o’er,

There is always two or more,

Running about, so I understand,

Hunting a place to put their land.

So I advise you to come to this state,

And get a claim before it is too late.

For the time will come if you don’t take care,

When you can’t get one a-floating around in the air.

—From “Rainbow Bend,” Winfield Courier, March 17, 1904, p. 1.

Lyrics – Some Pretty Little Girl Is Looking for Me

Verse 1

There are many pretty girlies living

in this little town,

But whenever they come near me

they at once begin to frown,

Some how they don’t seem to like me,

not one girl among them all,

Just because I can’t help talking

with a sort of little drawl.

Chorus

But, some where in this great countree

there’s a pretty little girlie

a’ lookin’ a’ lookin’ a’ lookin’ for me,

to do my cookin’ my cookin’ for me,

And altho’ I don’t know who it may be,

this sweet little girlie some day I’ll see,

That’s a’ lookin’ a lookin’ a lookin’ for me,

to do my cookin’ for me.

Verse 2

When I find this little girlie

then we’ll go to livin’ high,

And then all these little town girls

never dare come very nigh,

For I then will be so far beyond

their loving little call,

And besides they do not like me,

not a girl among them all.

Repeat Chorus

Lyrics – You Have A Mother At Home Boys

Verse 1

After the battle was over

And the smoke had cleared away

Many of the soldiers lay dying

At the close of this summer day

A few of the able ones had gathered

Near where a wounded comrade lay

As they stood with solemn faces

They heard their dying friend say

Chorus

You have a mother at home boys

I have no loved one to grieve

And e’n tho’ I should die now

There’ll be no dear mother to grieve

But I had a mother once boys

One that was as kind could be

So when you go back home boys

Will you kindly think of me.

Verse 2

After the war was over

And the bloody battles were o’er

Many of the soldiers were going

Back to their loved ones once more

As they thought of old trials and troubles

That had so slowly gone by

As they looked back o’er their battles

They tho’t of one last friendly cry.

Repeat Chorus

Notes About Sources

Baseball Statistics.

Major League Baseball, Retrosheet, and individual game accounts in Sporting Life are the sources for data about Patterson’s major league games. Sources for minor league data include the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball-Third Edition and SABR’s minor league statistics posted on the SABR Encyclopedia and Baseball-Reference websites. In the case of the latter source (as of December 2009), Patterson’s 1911 records for Quincy, Kewanee and Burlington were found under the “unknown” Patterson listing, and not attributed to him specifically.

Patterson’s minor league game total does not include several games in which he played for the Arkansas City Grays of the Class D Kansas State League (KSSL) in August 1910. Patterson is not included in the team’s roster posted on either the Baseball-Reference or SABR Encyclopedia websites, but he appeared in several box scores for the Grays over approximately 10 days during the period in which he was suspended by Fort Wayne. The McPherson Merry Macks, a KSSL team, filed a protest with the league president, claiming that Patterson was ineligible to play because of his Fort Wayne suspension. The Merry Macks requested that McPherson be credited with wins in their games against Arkansas City in which Patterson participated. Phil Hostutler, the league president, initially denied the protest, but documentation has not yet been found as to whether further action was taken.

Various newspapers were the sources for individual game accounts and mid-season hitting statistics.

Family History

Genny Kenslow, Patterson’s granddaughter, generously supplied family history information, and also shared a great deal of information she has collected over the years in researching Patterson’s baseball career.

Sources

Books

Dobbins, Dick and Jon Twichell. Nuggets on the Diamond: Professional Baseball in the Bay Area From the Gold Rush to the Present. San Francisco: Woodford Press, 1994.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff, ed. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball-Third Edition. Durham, NC: Baseball America, 2007.

Snelling, Dennis. The Pacific Coast League: A Statistical History, 1903-1957. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1995.

Standard Atlas of Cowley County Kansas. Map of Beaver Township. Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle & Co., 1905, 17.

Newspapers

Arkansas City Daily Traveler, 1908-13.

Blackwell Sun, 1908.

Boston Daily Globe, 1909.

Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, 1913.

The Daily X-Rays (Arkansas City), 1908-09.

Dallas Morning News, 1909.

Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 1910-11.

Fort Wayne News, 1910-11.

Fort Wayne Sentinel, 1910-11, 13.

Guthrie Daily Leader, 1909.

Hutchinson Daily Gazette, 1910-11.

Los Angeles Times, 1911-13.

Mascatine Journal (IA), 1911.

Morning Oregonian, 1913.

Oakland Tribune, 1911-1913.

Ogden Evening Standard (UT), 1913.

Oklahoman, 1909.

Oklahoma State Capital (Guthrie), 1909.

Oregonian, 1911-12.

Ponca City Daily Courier, 1908.

Salt Lake Tribune, 1913.

Sporting Life, 1909-13.

The Sporting News, 1911-13.

Van Wert Daily Bulletin (OH), 1909.

Wichita Eagle, 1908.

Winfield Courier, 1903-09.

Winfield Daily Courier, 1906-09, 13.

Internet

Major League Baseball—Historical Player Stats: mlb.com/mlb/stats (accessed 2009).

Retrosheet: retrosheet.org (accessed 2009).

Sports Reference LLC: Baseball-Reference.com/Minors, baseball-reference.com/minors/ (accessed 2009).

Society for American Baseball Research: SABR Encyclopedia, sabrpedia.org (accessed 2009).

Interviews, Family Recollections, Genealogical Materials

Kenslow, Genny (granddaughter of Clare Patterson). E-mail correspondence, personal interview, 2009.

_______. “The Baseball Player: A Short Story.” Unpublished short story manuscript.

Government Documents and Records

Certificate of Death (duplicate)—L.C. Patterson. California State Board of Health. Original created March 28, 1913; duplicate issued July 2009.

Kansas State Census for Cowley County, Beaver Township: March 1, 1895, and March 1, 1905.

Twenty-Fifth Biennial Report of the State Board of Health of California: Fiscal Years from July 1, 1916, to June 30, 1918. Sacramento: California State Printing Office, 1918. (available online at books.google.com)

United States Bureau of the Census. United States Census: 1900 (Cowley County, KS), 1910 (Fort Wayne, IN).

Other

Catalogue of St. John’s Lutheran College for the Academic Year 1906-1907. Winfield, KS: Tribune Printing Company, 1906.

Player File—Lorenzo Claire [sic] Patterson. National Baseball Hall of Fame, Giamatti Research Center.

Some Pretty Little Girl Is Looking For Me. Words by Clare Patterson, Music by J.H. Johnston. Chicago: E.L. Farnum Co., 1905.

A Tuberculosis Directory. New York: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, 1911; 1916. (available online at books.google.com)

You Have a Mother at Home Boys. Clare Patterson and Chas. Adams. Chicago: E.L. Farnum Co., 1905.

[1] No official record of Clare Patterson’s birth has been found. According to Genny Kenslow, his granddaughter, Sam and Hattie Patterson never lived in Arkansas City. The straight-line distance from the Patterson farm to Arkansas City was approximately eight or nine miles. (For the location of the farm, see the Beaver township map in the Standard Atlas of Cowley County Kansas – 1905). Patterson played baseball in Arkansas City as a young man, and he lived there for a time after he married an Arkansas City girl. However, no evidence was found that he was born there, or that Arkansas City was the mailing address for the Patterson farm. The notice of Patterson’s marriage license and documentation related to his attendance at St. John’s College both identified him as being from Oxford, a small Sumner County town located several miles north of the farm.

[2] Because the Rainbow Bend columns were not signed, some inference was made in attribution. According to the article about Patterson’s death in the Winfield Daily Courier on March 31, 1913, he was the newspaper’s Rainbow Bend correspondent for “several years.” Before he is believed to have assumed that role, a poem appeared in the Rainbow Bend column that was explicitly attributed to Patterson (see March 17, 1904 issue of the weekly Winfield Courier). Shortly thereafter, the incumbent columnist at that time, who may have been the Rainbow Bend school teacher, wrote a farewell column. Patterson’s first column is believed to have been published in the weekly Courier on April 28, 1904. During the next couple of years, especially, the columns often featured short verses similar in style to the poem that Clare is known to have written. In September 1906, Patterson was named as a Courier correspondent in an article about an upcoming picnic; this mention included reference to his interest in creative writing, i.e. poems and short stories. The appearance of Rainbow Bend columns was sporadic over the 1904-1908 period. In some cases, months would go by without one. Often these absences correlated with other known aspects of Patterson’s life, such as his attendance at St. John’s and baseball season. The columns disappeared in the summer of 1908. Many of the Rainbow Bend columns during the 1904-1908 period were written in a distinctive style unlike that used by other correspondents.

[3] “St. John’s Victorious: Southwestern Danced to the ‘Hi Lee Hi Lo,’” Winfield Daily Courier, May 11, 1906, 1.

[4] In the 1909-1911 period, minor league classifications ranged from Class A at the high end to Class D at the low end. In 1912 the range was Class AA to Class D.

[5] The July 9, 1908 Ponca City Daily Courier article that gave detailed player statistics also reported that Patterson’s average of .292 led all hitters with 50 or more at-bats. The reported average is several points higher, however, than the actual average based on the details provided, i.e. 40 hits in 140 at-bats.

[6] “Game Gossip,” Arkansas City Daily Traveler, August 12, 1908, 6.

[7] “’Ach, Du Lieber Louie!,’” Sporting Life, March 5, 1910, 13.

[8] The article about the game in the Oklahoma State Capital contained an internal discrepancy regarding the number of RBIs produced by Patterson’s double. The headline said two and the body of the article said three. See “Senators Beat Midgets,” Oklahoma State Capital, September 2, 1909, 7.

[9] “Guthrie’s Baseball ‘Find,’” Dallas Morning News, June 6, 1909, 31. Patterson and Clarke were both from Cowley County, but their homes were in different parts of the county. Clarke’s Little Pirate Ranch was located several miles north of Winfield, while the Patterson farm was several miles southwest of Winfield.

[10] “Outfielder Patterson Is Given Release,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, July 5, 1910, 6; “Patterson Is Only Man Burke Ever Suspended,” Fort Wayne Sentinel, July 6, 1910, 10; and, “Manager Burke Suspended Player to Maintain Discipline,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, July 7, 1910, 6.

[11] “Reddin Thinks His Place is Safe on Team,” Fort Wayne Sentinel, July 5, 1910, 8.

[12] “A Fort Wayne Outfield Change,” Sporting Life, July 16, 1910, 23.

[13] “Think Well of Patterson,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, January 1, 1911, 10.

[14] Newspaper accounts varied as to the specific circumstances. One indicated that the injury occurred in a play at second base while another reported that the play was at home plate. See “Patterson Is Out of Game,” Oregonian, October 9, 1911, 8; and, Sporting Life, October 28, 1911, 11. Also, an article appeared several months later suggesting that it was an ankle injury rather than a knee injury. See “Fight Will Be Made for Third Base for Oakland,” Oakland Tribune, January 31, 1912, 13.

[15] “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1911, 6; “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1911, 8; “Oaks Take Final Game and Series,” Oregonian, April 29, 1912, 10; “Drum Beats and Claire’s Homer Defeat Senators,” Oakland Tribune, May 27, 1912, 11; “Coast Pennant Race,” Oregonian, July 13, 1913, Section Two, 4; “Stream of Silver Pours Into Fund for Patterson,” Oakland Tribune, February 23, 1913, 22.

[16] “Krueger Puts His Pen to Contract,” Oregonian, January 31, 1912, 8.

[17] Oakland had been a Class A club in 1911 but, owing to a restructuring of class levels, became a Class AA club in 1912. Both classifications were the highest level in their respective years.

[18] For a description of the draft procedures, see “How the Minor Leaguers Are Drafted,” and “Oddities of the Draft,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1912, 2.

[19] Copies of the correspondence are found in Patterson’s player file at the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

[20] The exact progression of Patterson’s disease is not clear. It is not known whether he suffered solely from tuberculosis from the outset, or whether he also had typhoid fever and/or pneumonia at the time of his hospitalization in Portland.

[21] The doctor who signed Patterson’s death certificate, H.M. Elwood, indicated that he had attended Patterson from December 10, 1912 through February 15, 1913. Dr. Elwood apparently did not provide treatment to Patterson after February 15, but it is not known whether Patterson was under the care of a different physician during the final weeks of his life. A February 14, 1912 article in the Oakland Tribune indicated that two doctors had “given him up” at that point, but that a third one had taken charge. The death certificate listed only Mojave as the place of death. No hospital, institution, or street address was given, suggesting that Patterson was not in any kind of care facility.

[22] Billy Fitz, “Oaks Will Play Last Livermore Game March 19,” Oakland Tribune, March 18, 1913, 14.

[23] Earlier National Commission rulings had provided that players who were purchased need not be paid for unless they were actually delivered to the purchasing club. However, there apparently was no direct precedent for the Patterson situation. The Oaks’ position was that the earlier commission ruling was not applicable because the draft was an “enforced sale.” It is not known whether St. Louis eventually tried to recover their funds or, if they did, what the final outcome was.

Full Name

Lorenzo Clare Patterson

Born

October 5, 1887 at Arkansas City, KS (USA)

Died

March 28, 1913 at Mohave, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.