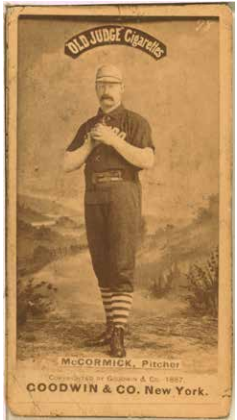

Jim McCormick

James McCormick amassed 265 victories from 1878 to 1887 in the National League and the Union Association. He possessed an excellent fastball and was one of the earliest pitchers to master the curveball. His repertoire also included a “drop” ball. Many fans believe he is an overlooked candidate for the Hall of Fame. Baseball-Reference, for instance, has a Hall of Fame Monitor ranking that gives McCormick 194 points. (A “likely” Hall of Famer would have approximately 100 points.1) Because McCormick pitched from less than 60 feet 6 inches and was prohibited from throwing overhand for half his career, he has not been given serious consideration.

James McCormick amassed 265 victories from 1878 to 1887 in the National League and the Union Association. He possessed an excellent fastball and was one of the earliest pitchers to master the curveball. His repertoire also included a “drop” ball. Many fans believe he is an overlooked candidate for the Hall of Fame. Baseball-Reference, for instance, has a Hall of Fame Monitor ranking that gives McCormick 194 points. (A “likely” Hall of Famer would have approximately 100 points.1) Because McCormick pitched from less than 60 feet 6 inches and was prohibited from throwing overhand for half his career, he has not been given serious consideration.

McCormick was a husky (5-feet-11 and 225 pounds in his prime), “lovable fellow with many admirable qualities.”2 With the Cleveland Blues from 1879 to 1882, he was the “club’s premier pitcher and the idol of baseball fans everywhere.”3 Despite the accolades, McCormick lost 128 games in that span while winning 127. The 128 losses were the most by any pitcher over four consecutive seasons.

McCormick was the son of James and Rosa (Lawry) McCormick. They were both born in Ireland, but moved to Scotland in search of a better life. James, called “Jimsy” by friends to avoid confusion with his father and later his son, was born in Glasgow on November 3, 1856. He was the third of six children, four born in Scotland and two in the United States. The family came to America in 1865 after hostilities had ceased in the Civil War. They settled in Paterson, New Jersey, where the father worked as a shoemaker and his mother as a housekeeper. McCormick had minimal schooling, possibly through the sixth grade. In the 1870 census he was listed as a cotton-mill worker when he was 13 years old.

Paterson was a hotbed for baseball. As a teenager, McCormick played with future Hall of Famer Mike “King” Kelly, along with future major leaguers Blondie Purcell, Edward “The Only” Nolan, andJohn “Kick” Kelly, on a team called the Keystones.4 Pitcher Nolan left the club in 1876 to join the Columbus Buckeyes, an early minor-league franchise. McCormick, with his red mustache and blue eyes, took over as pitcher. The Buckeyes recruited McCormick in 1877. When they disbanded in September, he was picked up by the Indianapolis Blues. Indianapolis joined the National League in 1878 and McCormick became the change pitcher for the flamethrowing Nolan. McCormick’s first major-league appearance came June 20 against the Providence Grays. The Blues dropped the game by a 7-4 score.

McCormick weathered injuries to make 14 starts and post a 5-8 record. On July 11, in a game against Boston, he broke a small bone in his forearm5 and was sidelined all of August. The Indianapolis News opined, “It is doubtful he will ever be enabled to pitch a ball again.”6 Reports of McCormick’s demise were premature because he was back in the box on September 3. His luck was no better as he broke a finger fielding a grounder. A plucky competitor, he took his spot on September 7 against Milwaukee and won 15-6. Indianapolis lost money in 1878 and failed to make the final payroll. McCormick reportedly lost $300 in salary.7

The franchise was shifted to Cleveland for 1879 and retained the Blues moniker. McCormick was originally supposed to be the change pitcher for left-hander Bobby Mitchell.8 Mitchell had slightly more experience than McCormick and as a left-hander he would be unique to the opposing batters. The Boston Red Stockings had the only other lefty in the league to see regular work, change pitcher Curry Foley. McCormick’s early-season performance was so impressive that he won the number-one spot. But Cleveland featured the league’s worst team batting, on-base, and slugging averages. Coupled with a below-average fielding percentage (.889) makes a 27-55 team won-lost mark no surprise. McCormick went 20-40 and appeared in the box for 546⅓ innings with a 2.42 ERA. His ERA was seventh in the league and ahead of three number-one pitchers. His 40 losses tied him with George Bradley of last-place Troy. Mitchell went 7-15, but with an ERA of 3.28.

After the season McCormick returned to Paterson and opened a saloon. He stayed in the business for more than 30 years with varying degrees of success. He also joined King Kelly and others on a New York all-star team. Perhaps the time he spent in that city led one anonymous baseball insider to suggest that “McCormick’s great ambition is to have a saloon in New York like Clapp and Lynch (catcher and pitcher from various teams in and around New York).”9 There is no evidence that McCormick ever expanded beyond Paterson. He became a member of the Elks and remained an active member his whole life.

Many publications have listed McCormick as the “manager” of the Cleveland Blues. In those days a team manager was more the business leader than the leader on the field. The team captain was more likely to handle the lineup and substitutions. The manager for Cleveland in 1879 was Joe Mack. According to numerous entries in the Cleveland Leader, shortstop Tom Carey was team captain. In 1880 Mack and Carey moved on to other baseball endeavors. Early speculation was that Fred Dunlap or Orator Shafer would earn the captain’s role. The team executive committee, headed by Ford Evans and Charles H. Bulkeley, named McCormick the captain on April 13.10

Cleveland revamped its roster, adding Shaffer, Dunlap, Pete Hotaling, Ned Hanlon, and Frank Hankinson to join holdovers McCormick, Bill Phillips, Jack Glasscock, and Doc Kennedy. The team batting average improved 19 points and the fielding totals were near the top of the league. With this added support, McCormick fashioned a 45-28 (the team record was 47-37) mark in 657⅔innings. He led the league in wins, complete games, and innings pitched, and finished fifth in ERA and second in strikeouts. The team took third place, 20 games off the pace set by Chicago. Modern-day statisticians give McCormick a WAR (wins above replacement) of 10.4 – far above any of his competitors.

The National League increased the pitching distance to 50 feet in 1881, but maintained the release point below the waist. McCormick chose to step down as team captain, and third baseman Mike McGeary was the choice of president Evans. McGeary’s tenure ended on May 19 and John Clapp took over as captain. McCormick was the workhorse again, leading the league in complete games while going 26-30. His backup was “The Only” Nolan.

In 1882 McCormick led the league with 36 wins as well as complete games and innings. His pitching WAR of 11.2 surpassed his 1880 season, but Cleveland still finished fifth. Partway through the 1882 season, the National League changed the pitching rules to allow the ball to be released below the shoulder.11

In 1883 five of the eight teams in the National League dropped the practice of a number-one man coupled with a “change” pitcher. They instead went to a two-man rotation with a third pitcher on the roster. Cleveland brought in Hugh “One Arm” Daily to pair with McCormick. Daily went 23-19 in 378⅔ innings. McCormick was 28-12 in 342 innings. Their third pitcher was Will Sawyer, who went 4-10 in 141 innings. The lighter workload agreed with McCormick. He led the league in winning percentage (.700) and ERA (1.84).

The Union Association was formed in 1884 to compete with the National League and the American Association. Suddenly there were 28 major-league franchises that lasted more than 50 games and 5 that dropped out along the way. America’s baseball talent was spread exceptionally thin and teams paid the price for their talent. Daily was an early signee with the Union Association. Cleveland replaced him with two rookies, John Harkins and Sam Moffet, to join McCormick in the box. The roster was also thin in the outfield and the trio of McCormick, Harkins, and Moffet made 67 appearances in the outfield. McCormick, who normally batted eighth or ninth, was elevated to the fifth spot in a lineup that struggled offensively.

McCormick suffered bouts with a lame arm that made him worry about his future. His catcher, Fatty Briody, had squandered all of his money and entertained thoughts of jumping leagues to help his finances. Briody, McCormick, and Jack Glasscock offered to be bought out by ownership with the intent of changing leagues. Cleveland management refused but looked into selling them to another team. It all came to a head in August.

On August 8 McCormick, Briody, and Glasscock met with officials of the Cincinnati Union Association club. The trio signed contracts to jump to the new league with a $1,000 bonus per man. Glasscock and Briody signed $1,500 contracts while McCormick signed for the same $2,500 he was making in Cleveland.12 In a bizarre twist, the trio played an exhibition game for Cleveland against Grand Rapids about an hour after inking their Cincinnati contract. This arrangement was made possible by the friendship of manager Charlie Hackett with Cincinnati president Justus Thorner.13 The Blues replaced the trio of defectors with players from the Grand Rapids squad after the game.

Briody summed up the decision to jump by saying, “I presume we will be blacklisted, but we have been playing ball for glory long enough. It is now a matter of dollars and cents.”14 Nine players were blacklisted during 1884, including the Cleveland trio. After the season, owner Henry Lucas of the Union Association St Louis Maroons convinced National League owners that admitting his team to the league would be a money-making proposition for all of them. Lucas also campaigned to remove the players from the blacklist and instead have them pay a fine. The owners agreed, and two levels of fines, $500 and $1,000, were created. The Cleveland players all were placed at the $1,000 level. All three played in 1885, but how the fine situation was handled is uncertain.

On August 10 McCormick took the box for Cincinnati against the league-leading St. Louis Maroons and came away with a 7-4 victory. He joined the Outlaw Reds (also known as the Cincinnati Unions) with the team in fourth place. Over the next 42 games they would climb to second, but still finish 21 games behind the Maroons. McCormick was in top form and posted a 21-3 record. The team went 35-7 over the last stretch of games. Glasscock and Briody contributed glowing statistics. Glasscock hit .419 and Briody .337. McCormick had posted a 19-22 mark in Cleveland. His combined workload with both teams made his WAR an astounding 14.5, tied for 10th best pitching value of all time. McCormick appears three times on the list of the 100 highest single-season pitching WAR’s in the majors. Only Walter Johnson (7), Kid Nichols (4), Cy Young (4), and Tommy Bond (4) have more.15

McCormick joined Providence in 1885 as the third pitcher behind Hoss Radbourn and Dupee Shaw. He was given a contract for $2,500, which was extravagant considering that he was used only four times in 10 weeks. He had a 1-3 mark when Cap Anson contacted the Grays about his services. The White Stockings needed a partner to team with John Clarkson. The Grays announced McCormick’s release on July 10 and then swapped him to Chicago for George Van Haltren and $2,000.

McCormick proved to be the perfect partner for Clarkson, who fashioned a 53-16 record (13.1 WAR). McCormick was 20-4 with the league’s eighth best ERA (2.43). The White Stockings won the pennant by two games over New York and faced the American Association champions from St. Louis in the postseason. The seven-game series ended in a tie, three wins for each squad and a tie game. McCormick posted a 3-2 mark in the series. McCormick earned a lifelong fan in manager Cap Anson, who called him “one of the best men … that ever sent a ball whizzing across the plate.”16

McCormick was paired with Paterson buddy Mike Kelly on the White Stockings. When the buddies returned to New Jersey they were given a parade that wound through the streets of the city. After the politicians feted them before an adoring crowd, “they drank all night in David Treado’s saloon.”17 McCormick and Treado became partners in the saloon/café business soon after.

Over the winter the National League owners tightened their belts and established a maximum salary of $2,000. McCormick was not pleased with a drop in pay, so owner Al Spalding wrote up a contract to cover the difference. If McCormick abstained from “malt or spirituous liquor” from mid-March to the end of October he would be given a $350 bonus. If Chicago won the league championship he would receive another $150.18

McCormick got off to a fantastic start on way to a 31-11 mark. However his performances became more and more erratic in the second half. By the time the postseason rolled around he was complaining of arm troubles and rheumatism. In his only start against St. Louis in the postseason, he was pounded, 12-0, and surrendered two home runs to Tip O’Neill as St. Louis won the series, four games to two.

In December when the White Stockings sent out contracts for 1887, they did not extend offers to McCormick, Kelly, Ned Williamson, Silver Flint, and George Gore. That quintet plus Billy Sunday had been noted for their fondness for alcoholic beverages. Sunday had realized his problem and made a well-publicized life change. As the story unfolded over days in the Chicago Tribune and other newspapers, the details emerged that Spalding had special bonus contracts with all five of the players. He had Pinkerton detectives follow them and make reports on their temperance habits. Based upon the Pinkerton findings, he called the players together during the season and fined them $25 apiece. This also cost McCormick his $350 bonus.

“After that they were just as bad and I am sorry to have to admit they were in no condition to play the Browns,” Al Spalding said.19 In January Spalding was still fuming about McCormick’s performance in the postseason. Of McCormick’s claim of rheumatism, he said, “Rheumatism! Bah! It was drink and nothing but drink. … He drank about as much as all the rest of them put together.”20

None of the players got their bonus money from Spalding and when Flint and Williamson eventually re-signed, they had temperance clauses in their contracts. Gore signed with New York, and Kelly moved on to Boston. After much speculation as to where he would play, McCormick signed with the Pittsburgh Alleghenys and was teamed with Pud Galvin and Ed Morris. McCormick signed for $2,500 and took nearly two weeks to get into shape before making his first appearance on May 13. He dropped a 3-2 decision to Indianapolis. More losses followed, including a 16-12 loss to New York in which he surrendered 28 hits and allowed 10 runs in the last two innings. His arm was still working into strong condition and he was unwilling to cut loose and throw his best heat. After a winless May, he finally beat Chicago on June 9. Pittsburgh finished the campaign with a 55-69 record. McCormick was 13-23, Morris 14-22, and Galvin 28-21. Only on rare occasions did McCormick show the skill he had in earlier times.

Nevertheless, Pittsburgh harbored hopes that McCormick would return in 1888. Sporting Life mentioned his name in nearly every edition. There was even a suggestion that McCormick wanted a three-year deal at $4,000 a year. What the front office did not know was that McCormick’s wife, Jennie, was ill with consumption (tuberculosis). She died on August 21, 1888, at the home in Paterson. When Cap Anson heard the news, “his stern and rigid mind became at once sympathetic in the extreme.” Anson remarked, “(T)hat is the greatest loss poor Mac can suffer. … God only knows what I would do were I to lose my wife.”21 King Kelly left his Boston teammates and went to Paterson to console McCormick. Kelly had a local florist make a tremendous floral wreath and then served as a pallbearer at the funeral. McCormick was left to raise a son, James, and daughter, Francis, on his own.

McCormick juggled his domestic duties with the saloon business until 1916, when he retired. He came down with a liver illness and lived with James, a police patrolman, in Paterson, for nearly a year before being admitted to the hospital. He died there on March 10, 1918.22 When informed of his death, evangelist and former teammate Billy Sunday said, “He was one of the best pals I ever had.”23 He was buried in the Elks Plot of Laurel Grove Memorial Park in nearby Totowa, New Jersey.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Last revised: November 9, 2022 (zp)

Sources

My sincere thanks to Bruce Bardarik at the Paterson library for providing important background. Also a tip of the hat to Eric Miklich as noted below.

Notes

1 baseball-reference.com/players/m/mccorji01.shtml. Scroll down to near the bottom of the page and see the “Hall of Fame Statistics” section.

2 Alfred C. Cappio, “Paterson’s Jim McCormick,” Bulletin of the Passaic County Historical Society, Vol. 5, No. 5, October 1961: 80-86. This excellent work has far too many anecdotes to relate here. This is the source of the nickname “Jimsy.” See also W.R. Rose, “All in a Day’s Work,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 13, 1918. Reports on his size vary at 5-feet-10 and 5-feet-11 with a weight from 210 to 225.

3 W.R. Rose.

4 Peter M. Gordon, “King Kelly,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/ffc40dac.

5 “McCormick Breaks a Bone in His Arm and the Bostons Score an Unearned Victory,” Indianapolis News, July 12, 1878: 4.

6 Indianapolis News, August 24: 4.

7 Indianapolis News, October 24, 1878: 1.

8 William McMahon, “James McCormick,” Nineteenth Century Stars (Cleveland: SABR, 1989), 85.

9 “Talks and Thoughts,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 16, 1884: 2.

10 “In and Outdoor Sports,” Cleveland Leader, April 14, 1880: 1.

11 19cbaseball.com. This website is maintained by SABR member Eric Miklich and is used here for the various rule changes during McCormick’s career. Eric was kind enough to advise me through emails in August 2016.

12 “Baseball Players Desert,” New York Tribune, August 8, 1884: 2. The Philadelphia Times, October 23, 1887: 14, used figures of $800 for Briody, $1,200 for Glasscock and $1,600 for McCormick.

13 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 9, 1884: 2.

14 Ibid.

15 baseball-reference.com/leaders/WAR_pitch_season.shtml. Accessed on September 4, 2016.

16 McMahon.

17 Al Del Greco, “The Silk City and Big Jimsey,” Paterson Morning Call, July 6, 1967: 20.

18 “Only Temperance Men: President Spalding Will Have No Others Next Year,” Chicago Tribune, December 2, 1882: 2.

19 Ibid.

20 “Chicago Ball Men,” Philadelphia Times, January 16, 1887: 11.

21 “McCormick’s Great Loss,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 22, 1888: 6

22 “Famous Old-Time Ballplayer Dead,” Paterson Morning Call, March 11, 1918: 3.

23 “Sunday Offers Tribute to Dead Pal of Old Days,” Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1918: 1.

Full Name

James McCormick

Born

November 3, 1856 at Glasgow, Glasgow (United Kingdom)

Died

March 10, 1918 at Paterson, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.