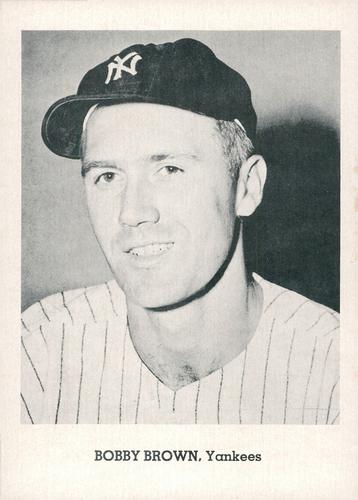

Bobby Brown

More than 19,000 players have played Major League baseball, but Dr. Bobby Brown’s life story has no parallel. He played professional baseball on a team that won five world championships, was a practicing cardiologist in Texas, served as interim president of the Texas Rangers, and spent 10 years as president of the American League.

More than 19,000 players have played Major League baseball, but Dr. Bobby Brown’s life story has no parallel. He played professional baseball on a team that won five world championships, was a practicing cardiologist in Texas, served as interim president of the Texas Rangers, and spent 10 years as president of the American League.

Robert William “Bobby” Brown was born on October 25, 1924, in Seattle, Washington, to William and Myrtle (Berg) Brown. His father’s career caused several cross-country moves, but Bobby excelled at baseball everywhere they lived. His father had been a semi-pro of some note with the Meadowbrooks in Newark, New Jersey. Bill Brown had even played against Lou Gehrig, when the latter played by the name of Lou Long.1 Bobby always felt that his father wanted him to give baseball a whirl, if consistent with his college plans and medical hopes.

Young Bobby was only 10 when he drop-kicked 24 field goals in a contest for youngsters staged by a Seattle, Washington newspaper, which tested football kicking and throwing skills. At age 12, he was playing American Legion Junior Baseball; by the eighth grade, he went to the try-out camp at Ruppert Stadium in Newark for the International League Newark Bears; and at 18, he was a freshman sensation at Stanford University, receiving offers from several Major League teams.

Bobby attended San Francisco’s Galileo High School, the same school as Vince, Joe and Dom DiMaggio, and Hank Luisetti, who was once considered America’s greatest basketball star. Brown was a straight-A student and president of the student body.

In 1941, while a junior at Galileo, he was noticed by a Cincinnati Reds scout, who had seen the Galileo squad destroy the University of California freshman baseball team. After the game, the scout, who was also a professor at Berkeley, asked young Bobby if he would like to go to Cincinnati and work out with the Reds. Bobby, a shortstop, promptly agreed. That summer he took the train to Ohio and worked out for ten days with the Reds, followed by an additional three-day workout when the team went to Chicago. After graduation from high school, Bill Brown sent his son back east to work out with the Reds, the Detroit Tigers, the New York Yankees, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Philadelphia Athletics.

Brown entered Stanford in 1942 expecting to major in chemical engineering. While still at Stanford, he enlisted in the navy in 1943. Called up for duty on July 1, 1943, he was assigned to a naval unit at UCLA and given five semesters to finish his pre-med courses. Brown was at UCLA for one year, where he played baseball for the Bruins and was then assigned to San Diego Naval Hospital for temporary duty.

On December 1, 1944, Brown was assigned to Tulane Medical School and was given a midshipman’s uniform. He played a year at Tulane, the 1945 season. With Brown on the team, the Green Wave had its most successful season to that point, winning 21 of 27 games, including 12 in a row, and Brown batted .444.2 When he was mustered out of the navy in January 1946, the scouts came calling.

Brown convinced the dean of the medical school at Tulane that he could play ball and still go to medical school. On February 18, 1946, he signed a contract with the New York Yankees that stipulated he would receive $11,000 for 1946, $15,000 for 1947, $18,000 for 1948, as well as receiving a cash bonus of $10,000. According to Bobby, that was the second highest bonus awarded up to that time. His highest per-season salary while playing was $19,500 (both 1952 and 1954), which was more than the dean at his medical school earned.3

Bobby was at Tulane when the 1946 season began and with the Yankees when it ended. He spent most of the year with Newark, the Yanks’ top farm team, where he hit .341. Jackie Robinson hit .349 for Montreal, edging Brown for the batting title. Because of his great season for the Bears, Bobby was honored in January 1947 at the Newark Athletic Club as one of the top four outstanding New Jersey athletes of 1946.

Brown was called up to New York after the International League season ended. The six-foot-one, 180-pound youngster made his Major League debut on September 22, 1946, playing shortstop and batting third in the second game of a Yankee Stadium doubleheader against Philadelphia. He got his first big-league hit in that game, as did his roommate Yogi Berra, also making his debut. Bobby appeared in seven games, going 8-for-24.

In 1947 Bobby batted .300 in 69 games, and then played an important role in the Yankees seven-game World Series win against the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Yankees used the 22-year-old, left-handed hitting Brown as a pinch-hitter four times, and four times he came through: two doubles, a single, and a walk. His fourth inning double in Game Seven tied the score at 2–2 and sent the eventual series-winning run to third base.

In the 1949 World Series, Bobby had six hits in 12 at-bats, including a double and two triples, and he drove in five runs. Then in 1950, when the Yankees swept the Phillies in the Series, Bobby went 4-for-12, with a double and a triple. The next season brought a fourth trip to the World Series for Brown. In five games, he had five hits in 14 at-bats with two walks. He had also won four world championship rings by the age of 26.

Between 1948 and 1951, Bobby averaged 104 games played per season, platooning with Billy Johnson (1948 to 1950) and Gil McDougald (1951) at third base. He was a steady contributor to the Yankees line-up. During this four-year span, Brown collected 364 hits in his limited time, sporting a .281 batting average.

In 1951 Bobby and his future bride, Sara Kathryn French, set their wedding date for October 12, 1951, which was shortly after the scheduled end of the World Series. The Yankees were playing in the Series against the New York Giants, but after Game Three, there was a heavy downpour that threatened to continue for a few days. Bobby and his bride had not planned a huge wedding, inviting only family and close friends, so he called her and changed the date to the 16th of October, giving enough extra time in case the weather combined with possibly four more games extended past the 12th.

The Series lasted six games. Brown batted .357 and the Yankees won another title. Brown’s 439 (18-for-41) career batting average in World Series play is the highest for batters with more than 20 at-bats.

Bobby and Sara were married at the Northway Christian Church in Dallas, Texas. Brown likes to tell folks that his was the only marriage postponed by rain. Following the honeymoon, he served as an intern at Southern Pacific Hospital in San Francisco.

On April 24, 1951, Bobby was shagging fly balls when he was called to the Yankees clubhouse. He was asked to treat Casey Stengel, who was suddenly overcome with nausea. As it turned out, Casey had had a kidney stone.

When the Korean War broke out, Dr. Brown was eligible for the “Doctor’s Draft,” since he had not actually served overseas during World War II. Consequently, he was sent to Korea to serve with the 45th Division in the United States Army and was assigned to the 160th Field Artillery Battalion, heading the battalion aid station. After 19 months of military service in Korea and at Tokyo Army Hospital, Brown returned to the Yankees in May 1954. The Yankees had lost nine of their first 16 games, leading Casey Stengel to exclaim, “Boy, do we need a doctor!”4

While at Tokyo Army Hospital, Bobby joined Joe DiMaggio and Lefty O’Doul to give clinics to the Japanese teams who were in spring training. Joe had brought his bride Marilyn Monroe to Japan for his honeymoon. Joe told the press the only doctor who could treat Mrs. DiMaggio was Lieutenant Brown.

Bobby Brown retired from baseball in 1954 at the age of 29. He had spent parts of eight seasons in New York, but he felt the calling to become a full-time doctor, a decision he never regretted. In 1974, Dr. Brown wrote, “the only regret I might have is that I didn’t play ball exclusively for two or three years. I’d like to know how well I could have done if I’d concentrated exclusively on baseball for several years.”5 His response is akin to Burt Lancaster’s line in Field of Dreams, when Ray Kinsella asks Moonlight Graham if he ever regrets becoming a doctor and not playing baseball. Dr. Brown will tell you, “Not going to medical school would have been a tragedy.”

After trading the bat and glove for a stethoscope and lab coat, Dr. Brown served his residency in internal medicine at San Francisco County Hospital from 1954 through 1957 (he was chief resident the last year). He then served a Fellowship in Cardiology back at his alma mater, Tulane Medical School, from 1957 to 1958. Following that, he entered private practice in Fort Worth, Texas, on August 1, 1958.

In May 1974 Brown took a six-month leave of absence from his medical practice to become interim president of the Texas Rangers. Brad Corbett, a good friend, had purchased the team and needed Bobby’s help. Coincident with his appearance, the Rangers moved into first place. “Modesty keeps me from taking the credit,” Dr. Brown told the Los Angeles Times. “Modesty and Ferguson Jenkins and Billy Martin.”6

In May 1974 Brown took a six-month leave of absence from his medical practice to become interim president of the Texas Rangers. Brad Corbett, a good friend, had purchased the team and needed Bobby’s help. Coincident with his appearance, the Rangers moved into first place. “Modesty keeps me from taking the credit,” Dr. Brown told the Los Angeles Times. “Modesty and Ferguson Jenkins and Billy Martin.”6

Brown knew he had his work cut out. “Texas is football country,” he once said. “We’ve got to get them interested in baseball.” The 1974 Rangers finished above .500 after two consecutive 100-loss seasons, but at the end of the ’74 season, Dr. Brown returned to his practice.

When Bowie Kuhn retired as Commissioner of Major League Baseball in 1984, the owners asked Bobby to interview for the job. However, the owners wanted a businessman to be the commissioner and offered Brown the job of president of the American League. It was a job he held for ten years, before Gene Budig replaced him on August 1, 1994. On August 10th, Bobby got on a plane to fly home to Texas. That was the same day the players went on strike, a strike that would end the season and cancel the World Series.

Brown visited the United States Military Academy in January 2007, meeting with cadets who were students in a sabermetrics course. He was very candid in his remarks. Regarding the state of baseball at that time, Dr. Brown said television is driving the huge amount of money being given to players. Attendance is higher than ever, and millions of people are subscribing to teams’ television networks.

He is amazed that the distances set up over 125 years ago have proven to be “just right”—ninety feet between bases and sixty feet, six inches to home plate from the mound. They’ve raised and lowered the height of the mound, but the horizontal distances are “just right.”7

The former American League President was proud of having very few controversies during his tenure, but a few incidents still stick in his mind. Dr. Brown’s toughest cases involved two marquee players. The first was when Roger Clemens was ejected in a playoff game against Oakland in 1990 for arguing balls and strikes. He received an eight-game suspension for the next season. The second involved Albert Belle, who was discovered to have used a corked bat on July 15, 1994. Belle received a seven-game suspension.

Brown believed steroids were a huge temptation for ballplayers to perform better. Cocaine was a major problem in baseball when he became American League president. In 1984, he had suggested testing for illegal drugs four or five times per season. His proposal called for random testing with no identifying names on the specimen bottles, to simply determine the extent of the problem. The players’ union refused.

Joe DiMaggio was the best all-around baseball player he ever saw, Brown said. Joe never gave inspirational talks, but he always played at 110 percent, so others played hard, too. In fact, Bobby recalled that no player on the Yankees gave big inspirational speeches. “We all got along. At the end of the day, everyone knew who had played well in a game.”8 It was an eight-team league in those days, but Bobby felt that nobody stood out like DiMaggio. From 1937 to 1973, it was 457 feet to left center field in Yankee Stadium. In any other ballpark, Joe might have hit well over 500 home runs. Having said that, Bobby said Ted Williams was the best pure hitter he ever saw.

In June 1949, The Sporting News interviewed Brown about his future in both medicine and baseball. He replied, “The basic truth is this: Just as long as baseball wants me, I will want baseball. Inevitably, there will be a day when I will have to say to myself, ‘The time has come. Hang up your spikes and your uniform, put away the bats, and get down to working out the Oath of Hippocrates.’”

The article ended with the following: “The day we talked with Brown, he was batting .333, and moving along impressively. A fine youngster, a credit to baseball, and he will be a credit to medicine. As he left to go out on the field, Bobby laughed, ‘Here are two more points. I will not wear a goatee as a doctor. And I am not engaged to be married.’ The future Dr. Brown pulled on his glove and walked out on the field to do a little laboratory work under the watchful eye of Prof. Casey Stengel.”9

Dr. Brown is a member of the Athletic Halls of Fame at Stanford, UCLA, and Tulane Universities, as well as those of Galileo High School, San Francisco Prep, and Greater New Orleans. He has received the Presidential Citation from the American Academy of Otolaryngology (1990), the Branch Rickey Award for Uncommon Service to Baseball (1992), and has been awarded three honorary doctorates (from Trinity College, the University of Massachusetts, and Hillsdale College). He was awarded the United States Coast Guard Silver Lifesaving Medal and served our country proudly during World War Two and the Korean War. He and Sara have three children and ten grandchildren.

Epilogue

Dr. Bobby Brown died at the age of 96 on March 25, 2021, in Fort Worth, Texas.

Related links

- Watch Dr. Bobby Brown’s panel discussion at the SABR 44 (2014) convention in Houston with Eddie Robinson and Bob Watson

- Listen to Dr. Bobby Brown’s SABR Oral History interview from 1994 with Tom Harris

Acknowledgements

The author expresses his sincere appreciation to Fr. Gabriel Costa, United States Military Academy, and Dr. John Saccoman, Seton Hall University, for their support in this project. Gabe and JT (both long-time SABR members) were instrumental in introducing the author to Dr. Brown and in offering advice with the biography.

Sources

Porter, David L., editor. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball, Revised and Expanded Edition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Personal conversations with Dr. Brown, January 2007 through June 2007.

Sporting News, June 8, 1949.

Sporting News, October 19, 1949.

The New York Times, May 4, 1954.

The Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1974.

Various undated articles and newspaper clippings (including contract cards) in Robert W. Brown’s file at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, The National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, New York, accessed May 2007.

Notes

1 Dr. Robert Brown, interviewed by the author, January 2007.

2 Bobby Brown file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

3 Dr. Robert Brown, interviewed by the author, January 2007.

4 Ken Freeze, “Kingfisher Crash off San Francisco,” Check-Six.com, http://www.check-six.com/Coast_Guard/9_May_1943_OS2U_crash.htm.

5 Bob Oates, “Calling Dr. Brown!” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1974.

6 Bob Oates, “Calling Dr. Brown!” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1974.

7 Dr. Robert Brown, interviewed by the author, June 2007.

8 Dr. Robert Brown, interviewed by the author, June 2007.

9 The Sporting News, June 8, 1949.

Full Name

Robert William Brown

Born

October 25, 1924 at Seattle, WA (USA)

Died

March 25, 2021 at Fort Worth, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.