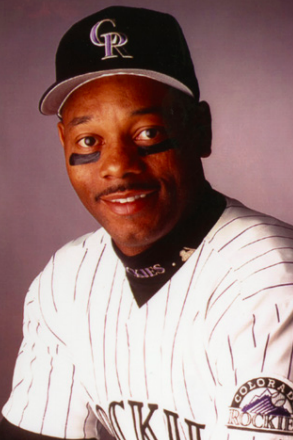

Ellis Burks

Few players in the history of major-league baseball have displayed each of the prized “five tools,” meaning the ability to hit for average and for power, to run, to field, and to throw. On that short list belongs the name of Ellis Burks, who began his major-league career as a 22-year-old rookie for the Boston Red Sox in 1987 and concluded it as a member of the 2004 Red Sox team that ended 86 years of frustration for the franchise with their World Series title. Burks had stops with four additional clubs, most notably with the Colorado Rockies, where he spent five seasons and where in 1996 he produced one of the greatest individual seasons in Rockies history.

Few players in the history of major-league baseball have displayed each of the prized “five tools,” meaning the ability to hit for average and for power, to run, to field, and to throw. On that short list belongs the name of Ellis Burks, who began his major-league career as a 22-year-old rookie for the Boston Red Sox in 1987 and concluded it as a member of the 2004 Red Sox team that ended 86 years of frustration for the franchise with their World Series title. Burks had stops with four additional clubs, most notably with the Colorado Rockies, where he spent five seasons and where in 1996 he produced one of the greatest individual seasons in Rockies history.

Ellis Rena Burks was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on September 11, 1964. When he was 3 his family moved to the state capital, Jackson, where he completed elementary school and his father worked as an electrician. As a child in Jackson he had no real opportunities to play organized sports but he learned to love baseball by playing sandlot games with his cousins. He was not particularly skilled at the game as a child, however, and his cousins used to tease him because he batted cross-handed and they liked to inform him, “You don’t know how to play, Ellis, you don’t know how to play.”1

At 10, the family moved to Fort Worth, Texas, and Ellis started to get serious about baseball, playing in a summer league after his freshman year at O.D. Wyatt High School. His varsity baseball coach, Bill Metcalf, would become an important influence upon him. As a sophomore, Burks was more than happy just to earn a varsity letter but Metcalf conveyed to the 15-year-old that he had uncommon instincts for the game and could become a special player.2 As a senior, Burks transferred to nearby Everman High School, the local baseball powerhouse. He had an outstanding senior season at Everman, playing for coach Jim Dyer. It was at Everman that Burks adopted the batting stance of his favorite major leaguer, Jim Rice. “I tried to look exactly like that in high school,” he once said. “I had his number, 14. I adopted his stance. My feet were pretty much placed the same as his in high school, junior college, and the minor leagues.”3

Despite a torrid senior season at the plate, college scholarship offers were slow to materialize. On one occasion his grandmother, Velma Burks, asked him about his college plans and Ellis informed her that he would be going to Ranger Junior College, although the coaches at Ranger had not yet contacted him with an offer to play baseball.4 He also entertained the thought that he might be selected in the major-league draft, but he escaped the notice of scouts despite the fact that he capped his impressive senior season by being the first high-school player to hit a ball out of Arlington Stadium.5 (He did it in a high-school all-star game.) His grandmother died in March of his senior year but Ellis honored his promise to her and committed to Ranger even after other schools began to show interest.

At Ranger Junior College, Burks played for coach Jack Allen. Allen was a master of homespun homilies delivered to full effect with a Texas drawl and he had quite the influence on the 18-year-old Burks. On one occasion, Burks hit a routine groundball to shortstop and was running to first at slightly less than full speed. Allen surprised Burks by inquiring if he was, perhaps, nursing an injury of some sort. When Burks informed him that he was fully healthy, Allen lectured him in no uncertain terms and stated, “By golly, I don’t care if you can throw a strawberry through a battleship or run a hole in the wind … on this team we play at full speed!”6 It was a lesson Burks would never forget and his hustle became a trademark of his professional career. The Ranger team was a real powerhouse during Burks’s freshman year and he led the parade by tearing the proverbial cover off of the ball throughout the fall season. He was excited because a number of scouts planned to attend a coming game, and he was shocked when game day arrived and Allen told him he wouldn’t be in the lineup because the coach was afraid the scouts would see him and that Allen would lose Burks, his best player, in the coming January draft. Burks assured his coach that, even if drafted in January, he would not sign with a pro team until the end of the spring season and Allen relented and allowed Burks to play the game.

Indeed, the scouts had a very favorable opinion of Burks and on the advice of scout Danny Doyle, he was selected by the Red Sox with the 20th overall pick of the January 1983 draft. Five of Burks’s teammates were also selected in that draft, including future major-league pitchers Mike Smith and Jim Morris. As Burks had promised Coach Allen, he did not sign with the Red Sox until the end of the spring college season.

Burks made his first stop in professional baseball with the Elmira (New York) Pioneers of the New York-Pennsylvania League as an 18-year-old playing short-season A ball in 1983. At the plate he hit just .241 that season with two home runs but demonstrated his range of abilities as he stole nine bases and contributed five outfield assists. He was promoted to high-A ball at Winter Haven in the Florida State League the following season where he was a full three years younger than the league average but displayed a mature set of skills. In 112 games for Winter Haven, he stole 29 bases and contributed 12 outfield assists. Burks had the good fortune of meeting his idol, Jim Rice, then still with the Red Sox. “I met him in spring training. I was in ‘A’ ball, and I got called up for a split-squad game. He was in the clubhouse. I said, ‘Excuse me, Mr. Rice, my name is Ellis Burks. It’s a pleasure to meet you.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I know who you are, kid.’” Burks added, “I was like, whoa, how does he know who I am?” I happened to sit beside him on the bench that day. I was pretty much in awe. I was too scared to ask him any questions. The next year, I was on the roster, and he told the spring-training clubhouse attendant to put my locker next to his. It was unbelievable to grow up idolizing a guy, and now he wanted my locker next to his.”7

Burks spent the 1985 and 1986 seasons at New Britain in the Double-A Eastern League and it was here that he really caught the attention of the big club. Red Sox coach Johnny Pesky became an admirer and declared that Burks “can run, hit, throw, and catch the ball. He may be ready for the big leagues sooner than people may think.”8 Burks’s ascent through the Red Sox system was slowed slightly by two right-shoulder injuries but his power began to blossom with 24 home runs over the course of the two seasons. It was the 31 stolen bases that he collected during the 1986 season in New Britain, however, that really caught the attention of the Boston front office. The Red Sox system had many promising young hitters in addition to Burks, including Mike Greenwell, Brady Anderson, Todd Benzinger, and Sam Horn, but it was the baserunning abilities Burks displayed that made him stand out from the other quality hitting prospects as the big-league club was sorely deficient in basestealing. (The 1986 Red Sox finished a distant last in the major leagues in stolen bases with just 41, of which six were by 36-year-old first baseman Billy Buckner.)

Burks made a strong impression on the Red Sox with an outstanding spring training in 1987. He was the team’s last cut, optioned to Triple-A Pawtucket.

The Red Sox did not have a strong sense of urgency to bring up their younger players to start the 1987 season; the team was coming off of a tremendously successful and memorable 1986 season in which they won their first American League pennant since 1975, and a heartbreaking seven-game loss to the New York Mets in the World Series. Lofty expectations for the 1987 Red Sox were misplaced as the team floundered to open the season. In late April, they had a 9-12 record and were in fourth place, 9½ games behind the high-flying Milwaukee Brewers. The Red Sox suddenly looked like a team that was past its prime and needed contributions from some of its talented prospects.

Burks had played a mere 11 games at the Triple-A level for Pawtucket when he was summoned to the big-league club. On the night of April 30, 1987, Boston manager John McNamara inserted 22-year-old Burks into the starting lineup as the Red Sox center fielder. Burks was batting ninth as the Red Sox faced pitcher Scott Bankhead and the Seattle Mariners in the Kingdome. Burks was hitless in three at-bats in a career that began with a weak groundball back to the mound, followed by a strikeout and a foul popup. He also dropped a line drive on which he had attempted to make a diving catch during the 11-2 Mariners victory. The game marked the first occasion that Burks had played on artificial turf,9 a circumstance that contributed to a base hit skipping past him in the outfield. Burks reflected great dismay and determination. “I felt bad after that first game. Everything happened so fast and I was not happy at what happened. I just wanted to come right back in my next game and show it wasn’t me,” he told a sportswriter.10 Skipper McNamara assured Burks that he would be in the starting lineup again the next game.11 The next night in Anaheim brought out the “real” Burks as he collected his first major-league hit in the second inning, a double down the right-field line off Urbano Lugo that brought home two runs. He went 3-for-3 as he shook off the jitters. In that series against the Angels, he showed a dazzling display of speed by sprinting from shallow center field to haul in a drive hit by Gary Pettis. Burks apparently liked Angels pitching because he connected for his first major-league home run, against future Hall of Famer Don Sutton, in the third inning of a game back in Boston on May 10. He later hit five home runs during a single road trip and brought his home-run total to 10 by June 18. When he hit a go-ahead home run off the Yankees’ Bob Tewksbury on June 21 it was the third time the rookie had provided the Red Sox with a game-winning blast.

Burks’s success fueled the Boston youth movement. In short order, Todd Benzinger, Sam Horn, and Jody Reed were promoted to the big-league club to join Burks and Greenwell and the look of the team began to change. Burks split time in center with Dave Henderson and they became close friends rather than rivals. In fact, Henderson provided great help to Burks in outfield positioning and in reading hitters and Burks later identified Henderson as one of his greatest influences and closest friends in the game.12 The front office liked what it saw from Burks so much in center field that it traded Henderson to Oakland on September 1. General manager Lou Gorman said, “Henderson’s home run put us into the World Series. He did everything we asked of him, but Burks just came along and took his job.”13 Don Baylor, who had provided enormous offensive and leadership contributions during the previous season, was also traded, to Minnesota. The 1987 Red Sox finished 78-84 but the infusion of young talent brought great excitement to Beantown.

Burks’s 1987 batting line exceeded all expectations with 20 home runs and 27 stolen bases to accompany 59 runs batted in and a .272 batting average. He became only the third Red Sox player to total 20 home runs and 20 stolen bases in the same season. He had 15 outfield assists, which as of 2017 remain the most in a season for a Red Sox center fielder. But Burks stood out for his entire game and his unusually refined skills, such as the ability to correctly read the flight of the ball off the bat. These defensive skills caught the attention of Lou Gorman who stated that Burks reminded him of a young Amos Otis.14 Don Baylor was notably impressed by Burks’ defensive prowess and paid him the highest of compliments by comparing him to Paul Blair.15

The young but talented Red Sox entered the 1988 season with high hopes. Burks set a personal goal of 40 stolen bases.16 However, a bone chip in his ankle required offseason surgery and he was unable to open the season with the team. Upon returning, he compiled six multihit games in his first nine games. A jammed left wrist slowed him temporarily but he finished the 1988 campaign with a .294 average, 18 home runs, 92 runs batted in, and 25 stolen bases. On September 4, the Red Sox assumed a permanent hold on first place in the American League East on their way to an 89-73 record and the American League East title. Postseason play was less noteworthy as the Sox were swept in four games by the Oakland Athletics as former Red Sox pitcher Dennis Eckersley saved all four games and Dave Henderson threw some salt in Boston’s wounds by going 6-for-16 with a home run. Burks was 4-for-17 in the series.

The 1989 season proved challenging for the team and for Burks. The team stumbled out of the blocks and was slow to recapture its form from the previous season. On April 30, the Red Sox faced the Texas Rangers in a game at Arlington as Nolan Ryan and Roger Clemens faced off on the mound. It was not much of a homecoming for Burks as a Ryan fastball in the first inning glanced off his shoulder and caught him behind the left ear. He was removed from the game and was not pleased with the situation. Burks said, “Why should I be when a guy who throws 100, throws one at my head?”17 The same two pitchers were matched up in their next start, at Fenway Park on May 5. This time Burks exacted some revenge against Ryan and the Rangers by going 3-for-4 with a stolen base. In the seventh inning a Ryan fastball zipped under Burks’s chin, causing Ellis to glare out at the mound and Ryan to take a step toward home plate. “I was making a statement,” Burks commented.18 In return, Ryan said, “Everyone was on edge because of what’d been said or written after the incident in Texas.”19 When order resumed, Burks fouled off a couple of pitches and then singled home Jody Reed to give the Red Sox the lead for good in a 7-6 victory.

New Red Sox manager Joe Morgan was very impressed with Burks and considered him to be highly capable in every aspect of the game. “He’s way above average in everything,” Morgan said. “Hitting, hitting with power, throwing, running, catching the ball. Everything. And he’s a good fellow. The other day I yelled out to him, ‘Burks, I hope you never change,’ and he said, ‘I won’t change.’”20 The biggest challenge Burks faced seemed to be staying healthy. While attempting to make a diving catch in a game against Detroit on June 14, he tore cartilage in his left shoulder. He underwent surgery and missed the next 41 games. The season came to an abrupt end for Burks during a September 6 game in Oakland in which Burks had gone 3-for-3 before he suffered a shoulder separation in a collision with Mike Greenwell in the outfield and surgery became necessary. Burks was limited to 97 games in the 1989 season, batting .303 with 21 stolen bases.

Burks completed a strong 1990 season that led to some overdue recognition as one of the top players in the game. He batted .296 and contributed 21 home runs and 89 runs batted in as the Red Sox compiled an 88-74 record and won the AL East Division title. His clutch hitting was particularly important as 23 of his first 43 runs batted in were delivered with two out. Against Cleveland on August 27, he became the 25th major leaguer to hit two home runs in one inning. The team’s stay in the postseason was again brief; they fell once again in four straight games to the Oakland Athletics in the ALCS. Burks went 4-for-15 in the series. Burks received a Silver Slugger Award as a recognition of his excellence over the 1990 season. He was the only 20-home-run hitter that season for a Red Sox franchise traditionally known for its power. He also earned his first Gold Glove Award, joining fellow outfielders Ken Griffey Jr. and Gary Pettis. He was selected for his first All-Star team although he did not play in the game due to injury. Burks finished 13th in the American League MVP voting.

The subsequent two seasons in Boston brought a steady diet of frustration. The 1991 season was seriously compromised by tendinitis in both knees and continual back pain. The tendinitis disrupted Burks’s timing and power at the plate and he had only two home runs in his first 29 games. The back pain increased over the course of the year and kept him out of the lineup for 11 games during a key late-September stretch run. The back problems proved to be a persistent foe over the coming years and Burks was later diagnosed with a bulging disk. His totals for the season reflected the extent to which he played hurt as he had only a .251 average with 14 home runs and 56 RBIs. A better reflection of the effects of the injuries was his uncharacteristically poor success rate on the bases with only 6 stolen bases in 17 attempts.

Trade talk percolated after the 1991 season but new Red Sox manager Butch Hobson was committed to Burks and batted him primarily in the leadoff spot in 1992. The knee problems compromised Burks’s speed and these issues were compounded when he played on artificial turf. The back problem did not respond to rest and medication and his season was limited to 66 games and 235 at-bats, which yielded an uncustomary .255 batting average with 8 home runs and 30 runs batted in. The Red Sox did not tender Burks a contract for 1993 and he was left off the team’s original 15-man protected list for the expansion draft, only to be pulled back when the Rockies selected Jody Reed.21 Nonetheless, the Red Sox made no effort to sign him.

The Chicago White Sox emerged as the club with the greatest interest in Burks and he signed with the team in early January of 1993. The White Sox had assembled a talented and experienced team, and in spring training, GM Ron Schueler commented, “ … Right now, Ellis looks as good as I’ve seen him look since I was scouting him years ago. If we can keep him going, he would give us a whole added dimension.”22 On April 16, and in his ninth game as a member of his new team, Burks made his return to Fenway Park. Facing Danny Darwin in his first at-bat of the game, Burks turned on a 3-and-2 pitch and launched a shot well over the left-field wall. As he rounded the bases, Burks received a standing ovation from the 26,536 fans. He commented, “It hasn’t been an easy transition. … I gave it a lot of thought this winter how it would be in this game. In spring training it hit me — I was wearing different colored socks.”23 The 1993 season marked a strong return to form for Burks. He batted .275 with 17 home runs and 74 RBIs. More importantly, he was able to stay free of serious injury and played in 146 games. The White Sox realized expectations in winning 94 games against 68 defeats and claimed the American League West title. They met the Toronto Blue Jays in the American League Championship Series but fell, four games to two. Burks went 7-for-23 with a home run.

Burks became a free agent after the season and all indications were that he would re-sign with the White Sox, where he felt wanted and appreciated. “I’ll take anything — three years, five years, ten years — whatever they want,” he said. “It’s been great here. One of the reasons I wanted to come here in the first place was a chance to win, and we’re doing that.”24 But the White Sox offered only a two-year deal and wanted Burks to play right field25 and so he was willing to consider other offers. The Colorado Rockies sorely needed a quality center fielder and offered Ellis a three-year, $9 million deal, which Burks accepted.

A new chapter in Burks’s career began when he signed with the Rockies but the story had some familiar elements. In Colorado he was reunited with two teammates from his rookie year in Boston in manager Don Baylor and hitting coach Dwight Evans. Playing for the Rockies had an additional allure as the franchise had just set a major-league attendance record in their inaugural season by drawing nearly 4.5 million fans to Mile High Stadium. Playing there was a hitter’s dream and a pitcher’s nightmare as the altitude and reduced air resistance translated into additional carry on batted balls. Defense became a priority in this park, and particularly in the outfield, where outfielders needed speed and arm strength to handle the largest outfield in the majors. Playing 81 games a year in Denver also came with costs, including the physical demands of playing long games and chasing down a lot of batted balls yielded by a pitching staff that had the National League’s highest ERA during the previous season.

The 1994 season was the second and final season for the Rockies at Mile High Stadium. They moved to Coors Field in 1995. Burks began the 1994 season just as he and the Rockies had hoped. He hit a home run off Curt Schilling of the Philadelphia Phillies in his first at-bat at Mile High Stadium and he was batting a lofty .354 with 12 home runs through his first 34 games. However, in a game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on May 17 he tore a ligament in his left wrist on a checked swing. He missed the next 70 games and when he returned to the club, every swing of the bat proved to be painful. He was limited to 42 games but still managed to hit .322 with 13 home runs. The 1994 season was shrouded by the specter of labor unrest and there was little movement in talks between owners and players as the season progressed. Indeed, the players union struck and the season concluded for the Rockies and all of the other major-league teams on August 11, and the 65,043 fans in attendance that night witnessed the last major-league baseball game to be played in Mile High Stadium, an otherwise forgettable 13-0 pasting of the home club by the Atlanta Braves. The Rockies finished 53-64 in their abbreviated season. Burks underwent surgery immediately after the season ended and his wrist remained in a cast for three full months following the surgery.

Resolution of the labor dispute was not reached until April 2, 1995, after a 232-day work stoppage that wiped out all 1994 postseason play. After an abbreviated spring training, the Rockies opened the 1995 season on April 26 in their brand-new ballpark, Coors Field. The 1995 lineup featured the “Blake Street Bombers,” so named because Blake Street bordered the new ballpark on the east side and the lineup contained an assemblage of certifiable sluggers that included Burks, Andres Galarraga, Dante Bichette, and Larry Walker. Vinny Castilla proved to be an unexpected but formidable additional power source and became the fifth member of the brigade. On April 26, the Rockies baptized their new park in unforgettable fashion as Bichette hit a three-run walk-off home run in the 14th inning off Mike Remlinger of the New York Mets to provide the 47,228 fans with an 11-9 victory. Burks was not able to join the fun until May 5 when he came off of the disabled list. The strong play of Mike Kingery in center field in his absence, and the presence of Bichette in left field and Walker in right field resulted in limited playing time for Burks for the rest of the season. His first home run of the season did not come until June 2 when he launched a walk-off pinch-hit three-run homer against Dan Miceli to beat the Pirates. Burks was able to play in only 103 games with 14 home runs and a .266 batting average to show for his injury-limited 1995 season. The team finished just one game behind the Los Angeles Dodgers in the National League West and they earned their first postseason berth courtesy of the wild-card spot. The Rockies lost three games to one in the first round of the postseason to the eventual champion Atlanta Braves as Burks went 2-for-6 in limited postseason playing time.

Burks arrived at spring training three days early in 1996 knowing that quality preparation and good health were going to be the keys to his success during the coming campaign. “For years I’ve just been trying to stay healthy and to get rid of that stereotype that I can’t stay away from injuries,” he said.26 More than anything, he was determined to erase the memories of 1995 when he was relegated to a role as the Rockies’ fourth outfielder. He was slotted to spend more time in left field during the season as manager Baylor wished to minimize the wear and tear on Burks and to see if center field might be a fit for the athletic Larry Walker.

A full season of good health enabled Burks to have a remarkable turnaround in 1996 and he carried the Rockies offensively as injuries to Walker and Bichette severely affected the team’s attack. Burks played in a career-high 156 games, and 129 of those games were spent in left field. His .344 batting average was second in the National League only to Tony Gwynn’s .353 mark, and he led the league with 142 runs scored and also drove in 128 runs. Burks’s 93 extra-base hits, 392 total bases, and .639 slugging average all led the league. Although some skeptics attributed his numbers to the “Coors Field Effect,” his road statistics were more than sufficient to reject that notion. Away from home, Burks hit .291 with 17 home runs and had 49 runs batted in with a .903 OPS in 75 games.

As Burks went, so went the Rockies in 1996. He batted .413 with 10 home runs when leading off an inning. He hit .362 with runners in scoring position and .369 with two outs and runners in scoring situations that year. Against the vaunted Atlanta Braves staff that featured three future Hall of Famers (Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz), Burks hit .380 (19-for-50). His 32 stolen bases were more than he had compiled in the previous five seasons combined. He joined Henry Aaron as the second player in history to record 40 home runs, 200 hits, and 30 stolen bases in a season. He finished third in the NL MVP voting behind Ken Caminiti and Mike Piazza and he received his second Silver Slugger Award. His WAR of 7.9 led the Rockies. Galarraga (47), Burks (40), and Castilla (40) became the first trio of teammates to reach 40 home runs in a season since Davey Johnson, Darrell Evans, and Henry Aaron accomplished the feat for the 1973 Atlanta Braves.

Burks became a free agent but was re-signed by the Rockies for the 1997 and 1998 seasons with an $8.8 million deal that included incentives. Burks had no regrets about re-signing and commented, “I signed early because I knew what I wanted. I’m sure I could have gotten a lot of money elsewhere. But money isn’t the main issue with me.”27 Preseason expectations were high for the club in 1997 as Walker and Bichette were expected to make stronger contributions after their previous injury-plagued seasons. In fact, Walker contributed even more than expected with 49 home runs, 140 RBIs, and 33 stolen bases to accompany a .366 batting average that earned him the National League MVP Award. Burks began 1997 slowly but his first four hits were home runs. His biggest nemesis during the season was a groin injury that caused him to miss a full month and he reinjured the groin in his second game back. He also had wrist and ankle injuries that lingered throughout the season and limited him to 119 games. Nonetheless, he batted .290 with 32 home runs and 82 RBIs and had a .934 OPS. His season total of just seven stolen bases, however, was evidence of the physical limitations he encountered during the year.

As the 1998 season opened, Burks said he felt he could not continue to play center field beyond the current season due to the effects of the hamstring, back, and knee problems that continued to limit his mobility.28 One of the major highlights of his season occurred on April 2, when he connected off the Diamondbacks’ Brian Anderson for his 100th home run in a Rockies uniform. The Rockies fell from contention early in the season and they made a move to fill their need for a younger center fielder capable of patrolling spacious center field at Coors. At the July 31 trading deadline, they sent Burks to the San Francisco Giants for center fielder Darryl Hamilton and minor-league pitcher James Stoops. They later received another minor leaguer, Jason Brester, to complete the deal. Burks concluded his time with the Rockies with a .306 batting average and 115 home runs in 520 games, and his 1996 season will be remembered as one of the greatest individual seasons in Rockies history.

Burks was a solid contributor to the Giants, batting .306 with 5 home runs and 8 stolen bases as the team went 31-23 following his arrival to conclude the 1998 season in second place in the National League West. Manager Dusty Baker planned to play him in right field during the 1999 season and to provide Burks with scheduled rest days to reduce his injury risk. Two offseason knee surgeries resulted in pain and soreness that compromised his power as he began the season. As the season progressed, Burks began to drive the ball into the gaps. Despite playing just 120 games in 1999, he concluded the year with 31 home runs and 96 runs batted to go with a .282 batting average and a .964 OPS. He nearly became the first National League player to drive in 100 runs in fewer than 400 at-bats as he fell just four short of 100 in 390 at-bats. The Giants once again finished second in the NL West.

The 2000 season marked a strong return to excellence for Burks despite two additional knee surgeries in the offseason. He batted.344, which equaled his best mark, set in 1996 with the Rockies, and he complemented the high average with 24 home runs and 96 RBIs. Burks’s contributions in San Francisco were duly noted as the team had the best record in the National League with a 97-65 mark and won the NL West title by 11 games over the Dodgers. They fell in four games to the New York Mets in the National League Division Series, in which Burks was 3-for-13 with a home run.

Burks became a free agent after the season and the American League seemed like the logical destination: He could serve as a team’s designated hitter and limit his time in the field to accommodate the knee issues. In only 284 games in a Giants uniform, Burks had hit .312 with 60 home runs and 214 runs driven in. Remarkably, Burks had a better OPS with the Giants (.971) than he had in his previous five seasons in Colorado (.957).

The Cleveland Indians signed the 36-year-old Burks to a three-year, $20 million offer in 2001 with the hope that he could play 100 to 120 games a year. Burks broke his right thumb in mid-July but still hit 28 home runs and drove in 74 runs with a .290 batting average. The Indians won their division with a 91-71 record and headed to the ALCS, where they faced a Seattle Mariners team that had compiled an all-time major league record of 116 wins. Burks went 6-for-19 in the series with a home run but the Mariners prevailed in five games.

Burks assumed the designated-hitter role for the Indians during the 2002 season and showed what he could do when provided a full season with the bat. He played 138 games and had 32 home runs and 91 runs batted in to accompany a .301 average. He completed his fourth consecutive season with an OPS above .900 (.903) with each coming after the age of 34. After the season, Burks required surgery on his left shoulder but he was in the Indians’ starting lineup again on Opening Day in 2003. He began the season well and continued to drive the ball with authority through the early part of the year. However, right elbow pain hampered his swing and he was required to end his season on June 7 in order to undergo ulnar nerve reconstruction surgery. In his abbreviated third season with the Indians, Burks batted .263 with 6 home runs and 28 RBIs. The Indians released Burks after the season, but he was not yet ready to retire from the game.

Burks’ career came full circle when he signed with the Red Sox as a free agent on February 6, 2004. At a press conference he said, “I can let you know that I will retire a Red Sox.”29 He was attracted to Boston by his wish to finish out his career where it had started and also felt that the team had a chance to reach the World Series. In turn, the Red Sox felt that Burks’s leadership abilities provided an important contribution to a team hoping to finally end their World Series drought.

Burks appeared in nine of the team’s first 17 games but underwent additional knee surgery in late April. Although he was unable to resume playing for many months, Burks remained with the team and even accompanied the Red Sox on road trips as he recovered from his injury. His commitment to the team was duly noted and appreciated by his teammates and Burks later commented that he wanted to contribute in whatever way that he could to a team that he felt was destined to win the World Series.30 After missing nearly five months with the injury, he returned to the lineup on September 23. In the season’s next-to-last game, at Camden Yards in Baltimore on October 2, manager Terry Francona inserted Burks into the lineup for his 2,000th major-league game. Batting fifth and in the DH role, he singled in his first at-bat in the second inning of that game for his 2,107th and final career hit. In the bottom of the fourth inning he was replaced by rookie Kevin Youkilis. The Red Sox capped their dream season with their first World Series title since 1918 by sweeping the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series although Burks was not on the roster for the playoffs.

The 2004 World Series title vanquished the bitter memories of previous seasons and will always be regarded as one of the greatest accomplishments in Boston sports history. A largely unknown part of the story involves the team’s triumphant return home from St. Louis. As the plane approached Boston, Pedro Martinez asked for everyone’s attention and delivered an impromptu speech in which he recognized the contributions of the players on the field in contributing to the historic accomplishment. As Martinez continued, he singled out “The Old Goat” in reference to Burks and provided special praise for the teammate who had remained with the club and who had contributed his knowledge and leadership over the five long months of his injury rehab. At the request of Martinez and his teammates, Burks led the team down the steps of the plane to the tarmac at Logan Airport carrying the World Series trophy overhead.31

Ellis Burks retired after the 2004 season with a .291 lifetime batting average to go with 352 home runs. He is one of just a few major-league players to have hit 60 or more home runs with four separate teams. Injuries robbed Burks of the opportunity to put up even more impressive numbers and a possible berth in the Hall of Fame, but he looked back on his career with no regrets and said that he “loved every minute of it.”32 Burks received the respect of his peers for his professionalism and his willingness to play with pain. He remained in the game, working for the Cleveland Indians, Colorado Rockies, and San Francisco Giants.

The Ranger College baseball team now plays at Ellis Burks Field. As of 2017 Burks worked for the San Francisco Giants as an instructor, scout, and talent evaluator. He, his wife, Dori, and their daughters, Carissa, Elisha, and Breanna, resided in Chagrin Falls, Ohio. His son, Chris, began his own professional career in the Giants’ minor-league system in the summer of 2017.

Last revised: March 1, 2018

This biography originally appeared in “Major League Baseball A Mile High: The First Quarter Century of the Colorado Rockies” (SABR, 2018), edited by Bill Nowlin and Paul T. Parker.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Mel Antonen, “Red Sox Ellis Burks Steals Into the Spotlight: Fastest Player on the Team Learns by Survival,” USA Today, April 8, 1991.

2 Author interview with Ellis Burks, November 20, 2017 (Hereafter cited as Burks insterview).

3 Ellis Burks, as told to Matt Crossman. “My Idol,” The Sporting News, July 6, 2009.

4 Burks interview.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ellis Burks, as told to Matt Crossman.

8 “Minor Leagues,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1985.

9 Ibid.

10 Joe Giuliotti, “Burks Brings Raw Speed to Red Sox,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1987.

11 Burks interview.

12 Ibid.

13 Joe Giuliotti, “In Boston, the Spotlight Shifts,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1987.

14 Moss Klein, “AL Beat,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1987.

15 Ibid.

16 “AL East: Red Sox,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1988.

17 “AL East,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1989.

18 Phil Rogers, “Ryan-Roger Rematch Not So Hot,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1989.

19 Ibid.

20 Jerome Holtzman, “Red Sox’s Burks Really on His Way,” Chicago Tribune, May 4, 1989.

21 Joe Giuliotti, “Boston Red Sox,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1992.

22 Peter Pascarelli, “Bo or No, White Sox Look Like Contenders,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1993.

23 Joe Goddard, “Burks Homers in Homecoming,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1993.

24 Joe Goddard, “Burks Should Be Back in ’94,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1993.

25 Joe Goddard, “Chicago White Sox,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1993.

26 Tom Verducci, “The Best Years of Their Lives,” Sports Illustrated, July 29, 1996.

27 Tony DeMarco, “Colorado Rockies,” The Sporting News, December 30, 1996.

28 Tony DeMarco, “Rockies,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1998.

29 David Heuschkel, “Burks’ Return: It’s Been Ages,” Hartford Courant, February 6, 2004.

30 Burks interview.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

Full Name

Ellis Rena Burks

Born

September 11, 1964 at Vicksburg, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.