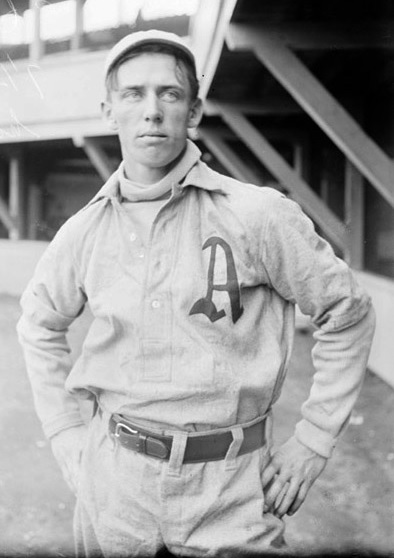

Danny Hoffman

Before Ray Chapman, Mickey Cochrane, Tony Conigliaro, Dickie Thon, and Adam Greenberg, the list of careers compromised by pitched baseballs claimed Danny Hoffman. On July 1, 1904, a Jesse Tannehill fastball caught the dynamic Philadelphia Athletics outfielder above his right eye, nearly killing him. Hoffman returned after months of recovery, and, despite significant damage to his eyesight, persevered to play another seven major-league seasons. But, like others who followed him, one pitch forever changed the trajectory of his baseball life.

Before Ray Chapman, Mickey Cochrane, Tony Conigliaro, Dickie Thon, and Adam Greenberg, the list of careers compromised by pitched baseballs claimed Danny Hoffman. On July 1, 1904, a Jesse Tannehill fastball caught the dynamic Philadelphia Athletics outfielder above his right eye, nearly killing him. Hoffman returned after months of recovery, and, despite significant damage to his eyesight, persevered to play another seven major-league seasons. But, like others who followed him, one pitch forever changed the trajectory of his baseball life.

Daniel John Hoffman was born on March 2, 1880, in Canton, Connecticut, to German-American parents. His father, John, hailed from New York, his mother, Wilhelmina (Minnie), from Connecticut, and they grew up on the same Canton street. Danny was their first son, the third of their seven children. By 1900, the Hoffman family had moved slightly to the west, to nearby Torrington. Here Danny worked in the Union Hardware factories, and pitched and played the outfield for the company team.1 A left-hander, he stood 5-foot-9 and weighed 170 pounds.

In 1901, Hoffman graduated to Roger Connor’s Waterbury Rough Riders of the Connecticut State League.2 Connor sold the team in midseason, and in 1902 launched a Springfield, Massachusetts, squad in the same league, recruiting Hoffman for the cause. The youngster emerged as a star. As “the premier southpaw of the league,” Hoffman compiled an 18-7 record.3 When in the outfield, he “covered wide territory” and his arm threatened careless baserunners.4 Hoffman led league regulars with a .336 BA and .522 SLG. He was a “good hard” opposite field hitter, and impressed as “one of the fastest men in the country getting down to first.”5 Once on base, his speed resulted in 47 steals.6

Hoffman attracted considerable attention that summer. Boston Americans manager Jimmy Collins made overtures to Springfield, as did Brooklyn’s skipper Ned Hanlon.7 Rumors surfaced that a comparative small-fry, Doc Reisling, Hartford’s manager–but slyly recruiting for the American Association Toledo squad he would take over next season–had collected Hoffman’s name on a contract.8 But it was Connie Mack who cut a deal with Connor in mid-October. Weeks earlier, Mack’s Athletics had taken their first American League pennant. When A’s center fielder Dave Fultz bolted to the National League, Mack purchased veteran Ollie Pickering to play center, between speedy left fielder Topsy Hartsel and slugging right fielder Socks Seybold. Despite Hoffman’s pitching success, Mack intended to use him “exclusively” for outfield depth.9

Several weeks into the 1903 season, Hartsel went down to injury, and Hoffman took his place in left. Then, as Hartsel returned, Pickering was lost. Mack shuffled Hartsel into center, leaving Hoffman in left. His “splendid showing” as a “very valuable substitute outfielder” helped keep the Athletics afloat in the pennant race.10 After finishing a sweep of the Browns on June 17, Philadelphia led Boston by 1½ games.

But the focus Rube Waddell brought to his breakout performance in 1902 was not always evident in 1903. On July 9, the irrepressible pitching ace announced that “outfielder Hoffman will come with me and we will play independent ball in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.”11 But Hoffman was in Toledo, likely the result of a squabble with Mack over salary.12 Mud Hens President Charles Strobel claimed Hoffman had indeed signed with Toledo the previous season. American League president Ban Johnson leaned heavily on his American Association counterpart, Thomas Hickey. The matter was resolved within a week, and Mack sent Hartsel west to fetch Hoffman. Johnson pointed to the affair as highlighting the need for a National Agreement between the major and minor leagues, under consideration that summer, to be consummated.13

Several weeks later, Philadelphia lost five of six games to league-leading Boston, and effectively fell out of the race. Hoffman continued to sub for Mack’s outfield starters, and finished his rookie season with a .246 BA/.267 OBP/.347 SLG over 74 games. The Athletics finished in a distant second place, at 75-60.

Hoffman proved even more valuable as the 1904 campaign launched. Starting in early May, Hartsel, Seybold, and Pickering went down in succession. Mack moved Hoffman from left to right to center, and from first to fifth to second in the batting order. Philadelphia, after losing a series opener in Boston on June 30, stood at 31-26, in fourth place, 5½ games behind the first-place Americans. Hoffman stood among the league’s hitting leaders.

The next day the Athletics faced Tannehill, a crafty left-hander known for his pinpoint control. Hoffman had already collected three singles before coming to the plate in the top of the ninth with two out, a runner on first, and Philadelphia behind, 4-3. Tannehill got two quick strikes on him. Hoffman expected an offering on the outside part of the plate. Instead, as Boston newspapers reported the next day, “one of Tannehill’s fastest balls” hit him “just above the eye” with a “crash that could be heard in all parts of the field.”14 For a moment, Hoffman felt “as if my head had been crushed to a pulp,” then collapsed to the ground unconscious.15 Some reports suggest his eye was at least partially dislodged from its socket.16 Two doctors—his teammate Doc Powers and the Boston team physician—administered what assistance they could. Waddell then carried the limp Hoffman to the Americans’ dressing room. From there he was taken to the team hotel. The Athletics rallied against an unnerved Tannehill to win the game. Hoffman never forgave the pitcher, later telling a reporter that “it was done with malice aforethought,” given his success against the pitcher earlier in the game.17

Hoffman remained unconscious for the next four days. He returned to Philadelphia on July 10 to begin treatment with local eye specialists. For the next two months, he struggled to sleep and lost significant weight. By Labor Day, as the Athletics were falling away from a close pennant race, Hoffman played in a (likely semipro) game in Connecticut. Later that September, he returned to Philadelphia, practicing daily as his teammates played out the string on a western road trip.18

The Athletics concluded the 1904 season with three doubleheaders in Washington. Hoffman wanted to play. Mack wanted to assess his recovery. Starting in left field in five of the six matches, Hoffman went 3-for-21, and finished the season with .299 BA/.329 OBP/.426 SLG marks. Subtracting this return performance, his sophomore line read .317/.346/.453.19 Mack unloaded the under-performing Pickering that offseason, placing faith in Hoffman.

“When I recovered I had a head harness to protect me,” Hoffman later recalled of his days in Philadelphia.20 In 1907, after a fan fractured Billy Evans’s skull with a thrown bottle, a newspaper noted that “if Umpire Evans had been wearing Danny Hoffman’s headgear he would not have sustained that injury.”21 Beyond these mentions, evidence of this headgear is elusive. Perhaps it was the inflatable canvas and rubber “head protector” that Philadelphia railroad agent Frank Mogridge had submitted for a patent in August 1904. “The use of my invention,” Mogridge argued, “will not only insure the batter against injury to the head from being struck by the ball, but will give the batter confidence and prevent him from being intimidated by the pitcher and rendered fearful of being injured by the ball pitched.”22 In January 1905, Mogridge received his patent, and Philadelphia sporting goods magnate A.J. Reach subsequently marketed the “head protector.”

Boston visited Philadelphia to open the 1905 season. After taking the opener against Cy Young, the Athletics faced the Americans’ top southpaw, Jesse Tannehill, on April 15. Hoffman “was made to look badly by Tannehill, who fanned him three times.” But he “fairly jumped into” the roped off crowd to make a “sensational” catch in the sixth. Then, after Tannehill exited the game, Hoffman tied the score in the ninth with an infield hit, as Philadelphia rallied to win.23

Hoffman did not lack for bravery stepping back into the box. But as his comeback progressed, his helplessness against lefthanders—especially those with a quality curve—became increasingly evident. On June 2, Washington’s Beany Jacobson fanned him three times. Chicago’s Doc White repeated the feat a week later. Mack summarized his outfielder’s plight in 1920: “The center of the field of vision was blank. If Danny was looking at you he couldn’t see you with his right eye. His field of vision was okay around the edges. He could see the second story of the building behind you and he could see your feet, but your face, at which his eye was pointed, would not register at all. Naturally he couldn’t see a baseball approaching.”24

From June 22 onwards, Mack started rookie Bris Lord in Hoffman’s place when the Athletics faced a left-hander.25 By mid-August, the Athletics stood a few games in front of the Naps and White Sox in the pennant chase. Hoffman prospered in the center field platoon. “A streak of greased lightning getting down to first,” he beat out bunts on a consistent basis.26 His “daring base running” helped him steal 46 bases, best in the AL that season.27 Fans throughout the league thrilled at his defense. Against the Browns on August 18: “His catch of [Ike] Rockenfield’s drive in the tenth was one of those seemingly impossible plays that is seldom witnessed on a ball field. The ball was speeding straight for the club house. Danny had to chase after the sphere and managed to pick it from the clouds, facing away from the pitcher. Whirling as he ran, he [almost] nailed [George] Stone at second. George had started to go to third, but reconsidered and slid back to the bag just in time to save himself.”28

Yet, from mid-September on, Hoffman mostly rode the bench. Then, after the Athletics took the pennant, Mack went with Lord in the subsequent World Series loss to the Giants. Only once, as a pinch-hitter striking out to end Game Four, did Hoffman appear. “The loss of the speedy and scientific Hoffman was accentuated by the costly failure of young Lord,” noted Francis Richter.29 Lord went 2-for-20, failed to execute bunts, and was picked off first in the finale of the five-game series.

“It is well known that Hoffman has been at outs with Mack for some time,” Bozeman Bulger reported from New York that November, “and the ill feeling was intensified by the refusal of the Philadelphia manager to let Hoffman take part in the world’s championship games.”30 Despite such rumors of discord, and trade talk, Hoffman remained with Philadelphia as the 1906 season began. But, as their squads played a benefit game for San Francisco earthquake victims on April 29, Mack and Highlanders manager Clark Griffith hammered out a Hoffman-for-Fultz deal.31 Essentially, Mack released Hoffman. Fultz was pursuing a legal career.

Mack’s biographer, Norman Macht, suggests that, despite a winter of further treatment for the outfielder’s eyesight, the Athletics’ leader increasingly felt Hoffman’s condition was permanent. Mack also found his outfielder a disruptive presence on the team: “He benched Hoffman after seven games. Danny complained. He aired his gripes to the rest of the players, seeking their sympathy and support against the manager.”32 The Sporting News later reported that the “deal was made while Mack was incensed at Hoffman for starting stories that were so manifestly fake that the Philadelphia papers declined to publish them.”33

New York provided a fresh start for Hoffman, and he spent two controversy-free seasons with the Highlanders. Yet, while his defense and speed continued to thrill fans, his struggles at the plate left them wishing for an upgrade. In 1906, the pitching of Al Orth and Jack Chesbro propelled New York to a 90-61 second-place finish. Battling injuries, Hoffman appeared in 100 games and achieved .256 BA/.318 OBP/.325 SLG marks.

In 1907, Hoffman bolted out of the gate. After several weeks, he led the league in hitting, and impressed local correspondents with his center field play and the “fastest [base running] ever seen in this city.”34 Hoffman cooled off considerably to post .253 BA/.325 OBP/.313 SLG numbers in a career-high 136 games. Griffith swapped him out of the lineup when possible against left-handers. Nonetheless, as he had in 1905, Hoffman again led the league in strikeouts. New York fell back into the second division. That offseason, looking to improve their pitching, the Highlanders threw Hoffman into a deal for the Browns’ Fred Glade.

Arriving in St. Louis “a brilliant if not reliable performer,” Hoffman started the 1908 season in right field, batting leadoff.35 Almost from the onset, manager Jimmy McAleer played rookie Al Schweitzer in Hoffman’s place when the opposition presented a southpaw. As a tight pennant race took shape, the Browns’ veteran pitching staff kept them in the fight. But the team’s outfield was a comparative weakness, with the hot St. Louis summer seeming to wear Hoffman down. Eventually the Browns fell off the pace, finishing in fourth place with an 83-69 mark. Hoffman contributed a .251 BA/.304 OBP/.322 SLG line in 99 games. That offseason, McAleer packaged him in a failed attempt to land Cy Young from Boston.

In 1909 he again started strong. “Hoffman is playing as good baseball these days as any man in the American League,” exclaimed a local sportswriter, and “he has become the idol of the St. Louis fans.”36 By May 26, he led the league in hitting and the Browns, after a slow start, had won eight out of ten.37 But that afternoon, sliding into third with a triple, Hoffman badly sprained an ankle. When he returned several weeks later, the Browns were out of the race. Hoffman finished with his best season since his abbreviated 1904 campaign: .269 BA/.349 OBP/.336 SLG in 110 games, and placing among the leaders in several defensive categories. St. Louis slid to a 61-89 finish.

Hoffman lost a step and battled illness, in 1910. St. Louis fans turned on him and his teammates, as the Browns fell into a 47-107 cellar. Manager Jack O’Connor waived him at the end of August to test his trade value but, finding little, retained him. Hoffman remained with the squad as the 1911 season opened. On May 25, in his final major-league at-bat, he pinch-hit for Jack Powell. Boston’s Marty McHale hit him with a pitch.

St. Louis released Hoffman to Indianapolis of the American Association. The Indians, after the 1911 season, sold him to their league rivals in St. Paul. In April 1913, Wilkes-Barre rookie manager Joe McCarthy purchased Hoffman. He played for the Barons for the next three seasons before hanging up his spikes and returning to Connecticut. Talked out of retirement by the Bridgeport franchise, Hoffman toiled for several weeks early in 1916 before leaving baseball for good.38

Hoffman and his wife, Minnie, managed properties, then operated a café, in Bridgeport. Minnie died in 1920; the couple had no children. By that time, Hoffman lived in Hartford, and worked at a gun factory, likely the Colt Armory. His health failing, he moved to nearby Manchester in 1921. On March 14, 1922, Danny Hoffman died from tuberculosis. He was buried in St. Michael Cemetery, in Glastonbury, Connecticut. Connie Mack, who remembered Hoffman as a “world beater,” fleetingly approaching Ty Cobb’s greatness, wired $100 to his surviving parents.39

Photo credit

SDN-001329, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum

Sources

The author is grateful to Tom Milanese, Danny Hoffman’s great, great grand-nephew, for generously sharing his knowledge of Hoffman’s life.

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Hoffman’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers/

Notes

1 Background on Hoffman’s family history: Tom Milanese, phone interview with the author, May 2, 2016.

2 “Connecticut League,” Sporting Life, April 13, 1901, 11; “In Connecticut,” Sporting Life, May 18, 1901, 9.

3 George McGlynn, “Springfield is Second,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1902, 5; George McGlynn, “Had Best Record,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1902, 4.

4 “Again Springfield Wins,” Springfield Republican, May 21, 1902, 3.

5 Connie Mack, “Tips by the Managers,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1902, 4.

6 “Gossip,” Boston Herald, October 26, 1902, 42.

7 “Sporting Notes,” Worchester (Massachusetts) Daily Spy, September 12, 1902, 5; George McGlynn, “Offers From Brooklyn,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1902, 1.

8 “Luring Away Ball Players,” Springfield Republican, September 6, 1902, 3.

9 Francis Richter, “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, October 25, 1902, 4.

10 Francis Richter, “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, May 23, 1903, 11; Ernest Lanigan, “Play Speedy Ball,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1903, 5.

11 “’Rube’ Waddell Has Deserted,” Detroit Free Press, July 10, 1903, 3.

12 Mack spoke at length with Hoffman on July 9, believing he had convinced the rookie to stay. Initially it was reported that Hoffman was unhappy with his playing time. See “Hoffman Quits Athletics,” Philadelphia Record, July 11, 1903, 9. After Hoffman returned, Richter reported dissatisfaction with salary was the cause. See Francis Richter, “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, August 1, 1903, 5.

13 “Hoffman With Toledo,” Detroit Free Press, July 12, 1903, 8; “Toledo Topics,” Sporting Life, July 25, 1903, 3; “Hoffman Will Return,” Philadelphia Record, July 19, 1903, 16; “Toledo Topics,” Sporting Life, July 25, 1903, 3; Jacob C. Morse, “Boston Briefs,” Sporting Life, August 8, 1903, 3.

14 Game accounts can be found in Tim Murnane, “Lost It in the Ninth Inning,” Boston Daily Globe, July 2, 1904, 5; “Athletics Won in the Ninth,” Boston Herald, July 2, 1904, 9. Hoffman’s recollections can be found in “Hoffman Recovering,” Boston Herald, July 9, 1904, 16.

15 “Hoffman Recovering”

16 Veteran [Horace Fogel], “Slow in Starting,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1904, 1; “Death-Lurking Pitched Balls,” Washington Herald, April 24, 1910, 29.

17 “Death-Lurking Pitched Balls”

18 Details of his recovery may be found in Hoffman Recovering;” “Death-Lurking Pitched Balls;” “Davis May Get in Game Tomorrow,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 11, 1904, 6; “Athletics Win in a Tight Finish. Plank, in Excellent Form, Holds Senators to Seven Hits and Nary a Pass,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 12, 1904, 6; “Passed Balls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 1904, 6; Jacob C. Morse, “Boston Briefs,” Sporting Life, October 1, 1904, 3; “Quakers Quail,” Sporting Life, October 8, 1904, 1.

19 Hoffman had two singles, one double, and one HBP in these games. See “Athletics Split With Senators,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 8, 1904, 10; “Athletics Make An Even Break Of It,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 9, 1904, 14; “Athletics Wind up the Season with Senators, Dividing Double-Header,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 11, 1904, 10.

20 Wagner [pseud.], “Connie Mack Fine Man to Work for, Says Hoffman,” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, October 16, 1911, 7.

21 “Baseball Briefs,” Washington Post, September 23, 1907, 8.

22 Frank Pierse Mogridge. Head Protector. US Patent 780899, filed August 6, 1904, and issued January 24, 1905. For background on Mogridge’s invention, and the evolution of the batting helmet, see Larry Granillo, “Searching for the History of the Batting Helmet,” The Sports Daily, http://wezen-ball.com/2010-articles/searching-for-the-history-of-the-batting-helmet.html, accessed May 9, 2016.

23 The Old Sport [pseud.], “Athletics Put the Fanatics on Edge,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 17, 1905, 10.

24 Norman Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007), 329.

25 On several occasions, however, Hoffman moved back into the outfield when either Hartsel or Seybold were lost to action.

26 “Tied With the Athletics,” (Cleveland) Plain-Dealer, July 11, 1905, 10.

27 “Sixteen Inning Game Results in Tie,” St. Louis Republic, August 19, 1905, 8.

28 “Athletics and St. Louis Played Sixteen Innings Tie, When Game Was Called on Account of Darkness With Score 3-3,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 19, 1905, 13.

29 Francis C. Richter, “Result of Battle of the Major Giants,” Sporting Life, October 21, 1905, 4.

30 Bozeman Bulger, “Hoffman for Dougherty,” (New York) Evening World, November 9, 1905, 14.

31 “Played Ball for Charity,” Philadelphia Record, April 29, 1906, 10.

32 Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years, 364.

33 “Health Impaired,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1908, 4.

34 “Jones Falls By the Wayside,” (Cleveland) Plain-Dealer, May 5, 1907, 2C; Joe Vila, “Strike Fast Gait,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1907, 1.

35 “Clever Southpaw,” The Sporting News, February 13, 1908, 4.

36 James Crusinberry,” Hoffman Now Better Than Ever Before,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 24, 1909, 10.

37 For a contemporary hitting leaderboard, see “Hoffman Leads Batters in the American League,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 27, 1909, 14.

38 For the bookends of Hoffman’s Bridgeport stint, see “Danny Hoffman, Hard-Hitting Outfielder, For Bridgeport,” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, May 13, 1916, 8; “The Passing Show,” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, June 12, 1916, 10.

39 Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years, 331; “Danny Hoffman to Be Buried Here,” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, March 16, 1922, 4.

Full Name

Daniel John Hoffman

Born

March 2, 1880 at Canton, CT (USA)

Died

March 14, 1922 at Manchester, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.