John Reilly

Born in Cincinnati on October 5, 1858, John Good Reilly would spend most of his life and nearly all of his baseball career in his native city. He passed his earliest years at his family’s home in the city’s East End, within walking distance of the Ohio River. The family’s circumstances were probably fairly comfortable, for John’s father, Frank A. Reilly, worked as a riverboat pilot and captain. He must have been good at his trade, for when the Civil War broke out he was assigned to serve as pilot of the St. Louis, the flagship of Admiral Andrew Foote, who commanded the gunboat flotillas that cooperated so effectively with Ulysses Grant’s armies early in the war. During the Federal Navy’s assault on Fort Donelson in Tennessee on February 14, 1862, a Confederate shell burst in the cabin of the supposedly invulnerable ironclad. Foote himself suffered a minor ankle wound, but Frank Reilly’s injuries were mortal.1

Born in Cincinnati on October 5, 1858, John Good Reilly would spend most of his life and nearly all of his baseball career in his native city. He passed his earliest years at his family’s home in the city’s East End, within walking distance of the Ohio River. The family’s circumstances were probably fairly comfortable, for John’s father, Frank A. Reilly, worked as a riverboat pilot and captain. He must have been good at his trade, for when the Civil War broke out he was assigned to serve as pilot of the St. Louis, the flagship of Admiral Andrew Foote, who commanded the gunboat flotillas that cooperated so effectively with Ulysses Grant’s armies early in the war. During the Federal Navy’s assault on Fort Donelson in Tennessee on February 14, 1862, a Confederate shell burst in the cabin of the supposedly invulnerable ironclad. Foote himself suffered a minor ankle wound, but Frank Reilly’s injuries were mortal.1

The widowed Ellen Good Reilly probably endured several lean years, and around the time the war ended her young son John was sent to live on a farm with his grandfather in Illinois. By the early 1870s, Ellen had remarried a clerk named Henry Schafer, and around 1872 she was able to bring her son back home to live with her. After his return home young John quickly became active at the two pursuits in which he would spend the rest of his life. On May 5, 1873 his mother signed a contract on his behalf to begin an apprenticeship at the Strobridge Lithographing Company, a thriving commercial art firm. Soon after, he began to play baseball for a team of fourteen-year olds across the Ohio River in Latonia, Kentucky.2

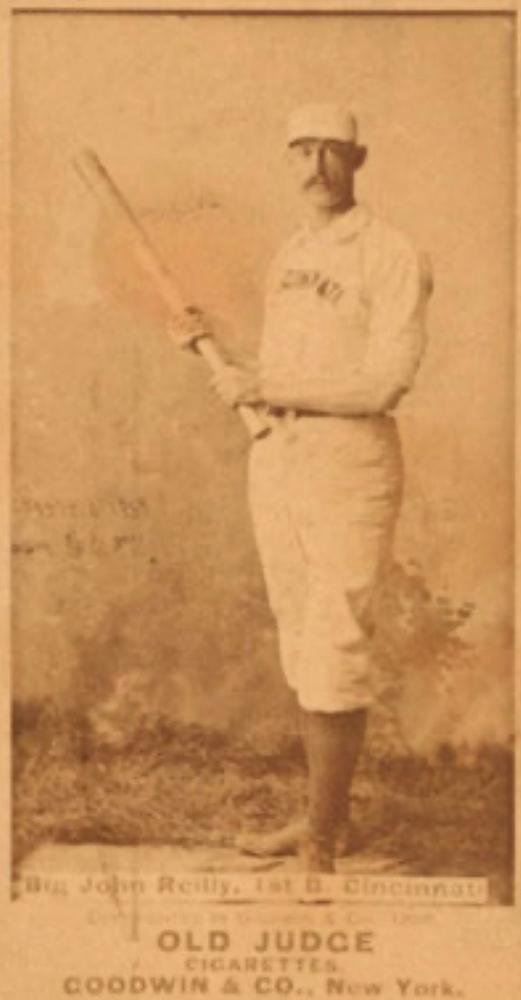

Reilly’s work at Strobridge would affect his baseball career in significant ways. If a story published in one of his obituaries can be trusted, that influence began from a very early date. Reilly started with the Latonia team as a catcher, but the rigors of playing in a day of minimal protective equipment made service at that position hazardous to a receiver’s hands and fingers, and thus to the career of the budding commercial artist. As a result, Reilly soon switched to first base, a position that proved ideal for him.3 No indication survives of how tall he was as a young teenager, but by the time he made his debut in a professional uniform, the Cincinnati Commercial was already referring to him by his nickname “Long John.”4 The mature Reilly was a lanky beanpole of a man, weighing less than 180 pounds but standing 6’3″ in a day when a man would stand out even among professional athletes if he reached six feet. In his amateur days he sometimes played the middle infield, and as a professional he filled in more than competently from time to time as an outfielder, but his height and agility made Reilly perfect for first base. As the Commercial would write, he “seems as much at home on first as if he was born and raised there.”5

From the Latonia club, the young Reilly moved on to play for a team called the Emmett Greens. The Greens were sponsored by three brothers named Ryan who owned a slaughterhouse, and their name was probably a tribute Robert Emmett, the first modern Irish nationalist hero. The Ryan brothers would presumably have been more than pleased to add to their roster a player with the impeccably Irish name of John Reilly, even if he had lacked the skills of Long John. Among the items in the Cincinnati Historical Society archives’ collection of Strobridge materials is a practice sketchbook signed, in large flourishes, “John Reilly, 98 Kilgour St., Cincinnati Ohio U.S.A,” which includes a variety of practice sketches made by the young apprentice, among them elaborate emblems for the “Emmet [sic] Green Stockings Base Ball Club Cinci” as well as a “Resolutes Base Ball Club.”

By the late 1870s Reilly was advancing in both his professions. After completing his apprenticeship with the Strobridge company in 1877 he was taken on by the firm as a professional artist and was soon playing for the best amateur baseball clubs in the city, teams such as the Cincinnati Stars and the Mohawk Browns, who also featured Reilly’s future major league teammate Ren Deagle, and Buck Ewing, who was then an infielder but would go on to be counted as perhaps the greatest nineteenth century catcher.

Cincinnati had by that time earned a unique place in baseball history, thanks to the famous unbeaten Red Stockings team of 1869, but since the collapse of that club at the end of the 1870 season, the Queen City of the West had found little to be proud of in a baseball way. A second professional team had been organized in mid-summer of 1875 and became a charter member of the National League the next year, but a succession of financial failures and last place finishes followed. Late in the 1879 season the latest owners folded the team, releasing the players early so they would not have to be paid for the usual post-season exhibition games.

A new organization now stepped onto the scene. The Cincinnati Stars had put together a nine consisting of some of the best local talent and built its own ball park on Bank Street in the West End, near downtown Cincinnati. Today, it would be unimaginable for a semipro organization to reorganize itself over the course of a winter and emerge as a major league baseball club, but this is exactly what happened in Cincinnati during the off-season of 1879-80. The Stars’ organization took steps to upgrade its roster to major league caliber, put the new team into the Bank Street Grounds and take over the Cincinnati franchise. Their application was accepted by the National League, and the city’s membership in the National League continued, seemingly without a break.

As a result of the reorganization the new club lost the rights to reserve the old team’s players and fell behind in the race to sign free agent talent. Unfortunate though this might be for club officials and Cincinnati baseball fans, it would turn out to be a good break for several of the city’s young players who would make their debut in the professional ranks with the 1880 Reds. The first to benefit was an eager young artist and first baseman. The new Reds gave a contract as utility man and eleventh man on an eleven-player roster to the best player on the previous year’s Stars team, Long John Reilly.

In the early going Cincinnati’s pitching was erratic, the hitting weak and there was talk of lineup changes. The team lost eight of their first nine games, and to add further gloom outfielder Al Hall of the visiting Clevelands suffered a career-ending leg fracture in a collision with a teammate. Having completed their three-game series, Cleveland and Cincinnati played a special exhibition game on May 17 as a benefit for Hall. This gave the Cincinnati management an opportunity to experiment with their team. Reilly had played poorly in his one appearance in a preseason exhibition, but he had partially redeemed himself by scoring the winning run after a tenth-inning double. Now, the infield was shuffled to give him another chance, and this time he acquitted himself well. On May 18 he appeared for the first time in a championship game, playing well again, and he would remain in the lineup for the rest of the year.

As a 21-year old rookie, Reilly was still outmatched by major league pitching. He was kept near the bottom of the Reds’ batting order and batted a meager .206. An unselective free swinger throughout his career, Reilly walked a mere three times and recorded 36 strikeouts in 272 at bats, more than fifty percent above the National League’s average strikeout frequency. No wonder that the day after his exhibition appearance the Cincinnati Enquirer on May 18 compared him to lightning, in that he “doesn’t hit anything often, but when he does the splinters fly.” However, he quickly made fans and admirers with his defensive play.

The most memorable event of Reilly’s rookie season occurred far from any ball field. A few weeks after Reilly was put in the lineup the Reds left home for an extended road trip. June 10 found them at Providence, where Reilly’s work at first base was singled out as a feature of the game. With a couple of off days in prospect, Reilly took off for a quick visit to New York. On the evening of June 11 he boarded the steamer Narragansett, sailing up Long Island Sound to begin the return voyage to Providence. Reilly later told a correspondent for the Cincinnati Enquirer that he had retired early and was fast asleep a little before midnight when he awoke to find himself thrown from his berth amid the loud creaking of timbers. The Narragansett had collided with another ship, the Stonington.6

Reilly made his way to the already water-covered deck, where a fire had started and passengers were beginning to panic. He climbed a mast and went to work with a knife supplied by another passenger to help free the ship’s lifeboats. At one point he fell into the water and nearly drowned, for the son of a river pilot who had lived most of his life within a short walk of the Ohio River was not much of a swimmer. Fortunately, he was able to grab a ladder and climb back on board. Reilly would recall seeing a man, maddened by fear and preferring a quick death to one by fire or drowning, raise a revolver to his head and shoot himself. He encountered an agitated woman who had stepped out of her stateroom at the time of the collision, locking her small children inside, and now found herself unable to open the door. Unable to find an axe, Reilly tried to break down the door with his shoulder, but the ship was listing so that he had to push upwards and could not gain the traction he needed to break open the door. With the ship in danger of sinking, he had to give up his efforts and abandon the children to their fate. Returning to the deck, he threw a plank into the water, then jumped in himself and grabbed it.

Reilly found the tide carrying him away from the rescue ships that were now coming into the area. He floated alone in the dark for what he later estimated might have been about an hour. He had nearly given up hope and was so tired that he had given up paddling and was drifting aimlessly when a boat from the City of New York found him and took him up. About mid-morning he arrived back in New York, where he sat on a dock for about five hours in socks, trousers and undershirt until a friend finally came to bring him some clothes.

That same day, June 12, the Reds resumed their series with Providence. The survivors had been taken to different cities, and no one knew whether Reilly was alive or dead but the Reds were expecting the worst. The Cincinnati Gazette‘s game account the next day observed that, “The sad news of the loss of John Reilly on the ill-fated Narragansett seemed to have a depressing effect on the Cincinnatis,” who lost, 11-4. The Cincinnati Commercial had also received an unconfirmed report of Reilly’s death but wisely withheld it for fear of alarming Reilly’s family unnecessarily. Two days later, the Commercial was able to report that Reilly himself had telegraphed from Providence to say he was safe.

On June 15 he was back in the lineup, and in spite of all he had been through he played his usual fine defensive game at first base. When he appeared on the field, spectators who had read accounts of his harrowing experience gave him a welcome far warmer than a visiting rookie first baseman would usually expect.

Nothing remotely as exciting happened during the rest of the 1880 baseball season. The Reds bumbled along trying in vain to escape the National League cellar. Among the young players they tried in their lineup were Joe Sommer and Hick Carpenter, who would be Reilly’s teammates on future Reds’ teams, and Harry Wheeler, the right fielder for Cincinnati’s 1882 American Association champions. Reilly survived the experimentation to last the entire season, but that fall the team encountered yet another in their series of management crises, and this time no reorganization took place. Cincinnati spent the summer of 1881 without a professional team, the only time this has happened since 1875. Like his native town, Reilly took the summer off from professional baseball, working for Strobridge and from time to time appearing as a member of various amateur clubs and pickup teams.

In the fall, a new professional club was organized, but Reilly disappointed local fans by signing with the Metropolitan Club of New York instead. Evidently counted on to make a stronger contribution in the field than at bat again, Long John began the season batting seventh but gradually moved up toward the middle of the Mets’ batting order. Over the course of the season he batted .258 and hit .235 in games against National League opponents. Modest as this was, it represented a substantial improvement over his 1880 showing, and it was good enough to lead the team.7

The Metropolitans, a strong independent team, played 162 games, more than any team had yet played in a season, winning 101 with four ties. Reilly appeared in 159 of them, tying shortstop Jack Nelson for the team lead and thus becoming co-holder of a new world’s record for games played in a season by an individual player, all the while carrying on a completely separate career in the mornings. Since the Mets rarely played on the road, Reilly was able to spend virtually every morning working at the New York office of the Strobridge’s firm, commuting to the Polo Grounds for ball games in the afternoon.

In Cincinnati, the reorganized Reds had entered the American Association, a fledgling rival to the National League, and after a slow start they cruised to the first championship. The Association’s teams were of minor league caliber compared to the National League’s, but with a circuit including six of the largest cities in the country, the new organization proved a big financial success. As the summer of 1882 waned its teams put their substantial profits to work signing stars from the National League and other clubs to contracts for the next season. John Reilly, in fact, committed himself to not one but two lucrative deals for 1882, first signing a contract with his home town Cincinnati team, then promising to sign with a National League team newly organized in New York by the Mets’ management. In the process he embroiled himself in the most embarrassing situation of his career, as he gradually tied himself up in knots trying to reconcile his conflicting commitments.

Cincinnati’s club secretary had signed Reilly in New York during August, but by the fall reports emanated from New York to the effect that he was claiming he had not actually signed with Cincinnati but only made a promise to do so, conditional on Strobridge’s agreeing to transfer him back to their home office in Cincinnati. Since Strobridge refused to do this Reilly claimed the Cincinnati agreement was invalid. Cincinnati newspapers told a different story. They said that Reilly had come home expecting the local team to grant him an honorable release from his contract with them. Frustrated by Buck Ewing’s similar repudiation of a Cincinnati contract to play for New York, the Reds’ management surprised Reilly by refusing his request, and then countering Reilly’s persistence by repeatedly raising their salary offer.

At last Reilly told club president Aaron Stern he could never play well enough to justify so large a contract. “In vain was he told that it was not because he or any other ball player was worth that much money to any club that the Cincinnatis would pay it, but because they wanted to show the country that one player from this city was honorable enough to stand by his written and sealed pledge, and to repay him amply for any advantage of which he might be otherwise deprived. He said no! no! no! to every thing” Soon, the popular home town hero’s standing had dropped so low that the Cincinnati Enquirer was observing sourly that “Reilly’s reported honesty and all such trash is on a par with the average player.”

Reilly finally promised Stern he would go east and ask for a release from his oral promise to sign with the New York team. By December, the Cincinnati Enquirer was claiming that Reilly “has signed but one contract — that with Cincinnati” and that New York was dropping all claims to him. If true, this stood Reilly’s earlier claims on their head, since he had originally named Cincinnati as the team he had never signed a real contract with. The whole matter was not solved until a peace treaty between the two leagues the following spring awarded him to Cincinnati. He was home now, and it would turn out that he was home to stay.8

Reilly returned to Cincinnati having matured as an offensive player. In June and July his play really took off, his finest performance perhaps occurring in a 6-0 win over the Athletics at Philadelphia on June 18 in which he contributed three singles and a triple and also played well in the field, once running over the scoreboard in an effort to catch a foul fly. But the best was yet to come.

On September 10, the Reds returned home after a disappointing road trip that had virtually ended all hopes of their repeating as American Association champions and began a homestand with a series against the Alleghenys of Pittsburgh. In the opener Cincinnati pounded out a 12-6 victory over the Alleghenys’ Denny Driscoll, who had been a Reds’ nemesis all year. Reilly sparked the win by homering in each of the first two innings, both times driving in Hick Carpenter ahead of himself.

The next day, Reilly singled in another easy victory for the Reds. On September 12, Cincinnati rolled over the Alleghenys, beginning with a nine-run first inning. Even among a host of impressive offensive performances, Reilly’s line in the box score stood out, with six hits in seven at bats as well as two stolen bases and six runs scored. In the bottom of the eighth, he drove an opposite field line drive to right field to score Carpenter again with Cincinnati’s fourth home run of the game. The hit finished the scoring in a 27-5 victory, and also completed a cycle for Reilly, who had already hit a double and triple to go with his three singles.

The next day the Reds finished a sweep of the Alleghenys, while Reilly went hitless. After several off-days the offensive assault resumed on September 18, but this time Cincinnati lost a tough game, 13-12 in ten innings, to the Athletics of Philadelphia. Reilly contributed a single and a triple and scored three times. On September 19, Reilly belted four hits in a 12-3 win and brought his hot streak to a climax by hitting for the cycle for the second time in a week.

After two more two-hit games, Reilly’s hot streak ended in a rain-shortened victory over Baltimore on September 22, when Orioles pitcher Hardy Henderson not only held him hitless but struck him in the hand with a pitch, forcing him to switch positions with right fielder John Corkhill. To add insult to injury, almost literally, Reilly did not even reach base on the play. The free base for a hit-by-pitcher had not yet been added to the American Association rulebook.

Between September 10 and September 22, Reilly had recorded 19 hits in 41 at bats, including two doubles, three triples and four home runs, for a batting average of .463 and a slugging average of .639, very good numbers at any time but all the more extraordinary in that day of low-power offense. In two innings on September 10, Reilly hit more round trippers than all but three of his teammates on the American Association’s leading home run hitting club did during the entire season. The four home runs he hit during his ten-day hot streak would have tied him for fifth among the league leaders in that category even if he had hit none at all during the rest of the season. Other batters have put together hot streaks, of course, but it is doubtful any of them have demonstrated an added dimension to his talent in quite the way Reilly did, when in the middle of his streak the Cincinnati Commercial published his caricatures of Athletics pitcher Jumping Jack Jones and umpire John Kelly on September 19 and 20.

The surge assured Reilly of the team leadership in batting average and the ownership of a bat inscribed in silver that was presented to the team leader in that category.9 His next season was still better. In 1884 he belted the ball for a .339 average and led the Association in home runs and slugging average. Modern readjustments of nineteenth century statistics leave him second to Dave Orr in the batting race and among the leaders in most other significant categories.

The next two years were relatively quiet ones for Reilly. The 1886 season was particularly difficult for him and for the Cincinnati team. A broken leg in mid-May put Reilly out of action for about a month, and injuries to third baseman Hick Carpenter and center fielder John Corkhill around the same time left the Reds short three regular position players. Sore arms in the pitching staff finished any possibility of the team’s living up to the high hopes for a pennant that had been raised at the start of the season when star pitcher Tony Mullane returned from a year’s suspension.

A disappointing season was made utterly miserable by a ferocious feud conducted by the Cincinnati Enquirer against almost everyone connected with the Reds. Matters culminated in June when the Enquirer loudly accused Mullane of throwing games in collusion with some Indianapolis gamblers. The charges collapsed when the Enquirer backed away from the story, declining even to present evidence before a special Association meeting called to consider the matter. That did little to help the Reds, who staggered home fifth with their first sub-.500 finish in five years in the American Association. Bothered by his injury, Reilly finished the season hitting a modest .265, but in a pitcher’s year this was still just a few points behind Charley Jones for the batting leadership among the Reds’ regular players.

Reilly came back to hit .309 in 1887, and his ten home runs made him the only man in the Association besides batting champ Tip O’Neill to reach double figures in that category. He followed in 1888 with his best season since 1884. After beginning the year by homering in five consecutive games, he went on to lead the league again in homers and slugging, as well as runs batted in, and he finished near the top in doubles, triples, hits and batting average. In a day when statistics calculated to a players’ last at bat were not available to everyone with a computer, hopes persisted into November that Reilly had won the Association batting crown. After a long delay, the official statistics finally showed Reilly finishing fourth in the race. Today, statistical readjustments have moved him up two places, but Tip O’Neill of St. Louis is still given credit for his second consecutive batting title.

At the peak of his career, Reilly was a well-established cornerstone of a strong and very stable Reds team. Although the Reds proved unable to repeat their 1882 championship and in fact would not win another pennant until 1919, the club remained a consistently high finisher during nearly all of Reilly’s career. His teams twice came in second in the Association race and, with the exception of the ill-fated 1886 campaign and his last season of 1891, they never fell below .500 or out of the first division. The core of the team was its infield, especially Reilly together with future Hall of Famer Bid McPhee at second base and Reilly’s 1880 teammate Hick Carpenter at third. These three men played together as regulars from Reilly’s debut with the team in 1883 until Carpenter was released on the eve of the 1890 season. “The seasons come and go,” the Pittsburgh Dispatch remarked, “but Biddy McPhee, Long John Reilly and Hick Carpenter always come winner in the shuffle, and look as natural around the bases as sign-boards at the forks of country cross-roads.”10

A free-swinging hitter who rarely walked and had difficulty adjusting his big swing to the bunting and place hitting that came into fashion during the late 1880s, Reilly nevertheless recorded consistently high batting averages. He had a strong throwing arm and, while a man of his size would hardly be a speed demon, with his long legs he covered ground rapidly enough and appeared repeatedly on contemporary lists of the Reds’ most effective base runners. In a day when most home runs were hit inside the park, his high totals for homers as well as triples testify to his speed as well as his power. He maintained the superior defensive skills that had kept him in the major leagues before his hitting had matured. In later years he would claim to have originated the practice of first basemen playing away from the bag, a distinction that was more frequently attributed to his contemporary, Charlie Comiskey of the St. Louis Browns. In fact, though, this practice had been followed sporadically for many years before Comiskey’s and Reilly’s time.

Reilly contributed to his team in other ways as well. He was an intelligent and sensitive man, of whom a rather florid obituary writer for the Cincinnati Enquirer would write, “An omniverous [sic] reader and student of human nature, ‘Long John’ found the characters of Dickens on every field and Thackeray’s folk on the highways and byways leading thereto. Had he cared to devote his pen to biography instead of the sketching pad, the ball-player artist might have been his own Boswell and the enthusiastic fans of the grand stand would have been the charmed devotee of the library fireside”.11

His self-disciplined and methodical habits extended even to his care for his playing equipment, particularly his bats. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, he scraped them with glass to get them just the right size. In the matter of attention to his bats, Reilly became known as the American Association’s only rival to the famous Pete Browning. The Enquirer said that hardly a week went by without Reilly receiving a new bat, as a gift either from a fan or from a manufacturer hoping for an endorsement, and he might try out as many as a dozen a week when he was slumping.12

Reilly was respected for his devotion to his team. He himself explained his viewpoint: “I like to see your crazy-mad players. The smiling fellows care only for their salaries and are no good to a team. … I’ve been in tight games when the paternity of every member of the team has been questioned, and after that it was over — the harsh words had all been forgotten.” Responding to reports that he was one of a group of Cincinnati players who had grown weary of the loud and abrasive team captain George Tebeau, Reilly emphatically denied the story so far as he was concerned. “[Tebeau] often grew mad and drew upon us the displeasure of the umpire, but his heart was all right,” he told the Cincinnati Times-Star. “He was playing to win.”13 That was enough for Reilly.

On the other hand, he had an unusual sense of sportsmanship, which his teammates did not always appreciate. In 1885 Tebeau’s predecessor as captain, Charlie Snyder, fined Reilly for telling umpire Billy McLean that he had not been hit by a pitch during a key game against Cincinnati’s archrival St. Louis.14 Four years later, when he was involved in a close play in a game against Kansas City and the umpire’s decision cost the Cowboys a run, base runner Jimmy Manning finally appealed to Reilly, who admitted Manning should have been called safe. By now, though, Reilly was apparently having second thoughts as to whether honesty was really the best policy, for after the game he remarked, “I had no business to interfere with the umpire’s decision.”15 The following winter Reilly described a similar incident in a game in Philadelphia, which he said had infuriated Tebeau, but that may have been an inaccurate memory of the Kansas City game.16

Reilly’s intense nature combined with a lively sense of humor and pungent manner of expressing his opinions to make him a favorite of sportswriters, and as the newspaper space devoted to baseball increased during the later years of Reilly’s career reporters, found him a prolific source of quotes. One of his jokes is worth quoting. Late in the 1886 season, some Reds players were discussing how to pitch to the Athletics team that was coming to Cincinnati for a series. Rookie pitcher Elmer Smith was concerned about Denny Lyons, the notoriously bibulous but hard-hitting Athletics third baseman. “Pitch him a drop, Elmer,” advised Reilly, meaning a drop ball. “Pitch him a drop and he’ll not hit it, for he told me he hadn’t touched a drop all summer.”

When Reilly was not having fun, however, he was sometimes at odds with less stable and team-oriented players. He stayed sober and in shape and expected his teammates to do the same, and he could be outspoken in criticizing those who failed to live up to his standards. According to a report in the Cincinnati Enquirer, Fred Lewis, a brilliant outfielder who was drowning his career in a sea of alcohol, ended his big league career in late August of the Reds’ nightmare 1886 season by punching Reilly in the face during a dispute over Lewis’ inability or unwillingness to play a game.17 The Cincinnati player who leaked this story, with complaints that Lewis was “a disturber” who criticized other players for their errors, was almost certainly Kid Baldwin, a talented alcoholic and perennial problem child for the club. There was also friction with two erratic pitchers, Tony Mullane and Leon Viau.

Nor was Reilly pleased after the 1888 season when Baldwin was given a contract containing a bonus provision for staying sober for the coming year. Club president Stern was trying to find an imaginative approach that might produce better results with Baldwin than former manager O.P. Caylor‘s approach, which had consisted primarily of lectures and fines, with the result that Caylor’s and Baldwin’s relationship eventually broke down completely. Some of the Reds veterans did not like Stern’s idea, however, and Reilly was characteristically outspoken on the subject. He bluntly told the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette on October 3, 1888, that the Baldwin contract showed it paid for a ball player to drink, for “then the management will pay him a big bonus to keep sober,” a prime example of the frankness that made Reilly a reporter’s favorite.

In spite of his fine play, the season of 1888 left Reilly with a sour taste in his mouth. A clubhouse fight with teammate Hugh Nicol and a season-long feud with umpire Herman Doescher made it harder to enjoy the year, and for the sixth consecutive year his team had failed to grab the pennant. From this time Reilly’s off-season conversations began to include talk about retiring – perhaps a salary ploy, perhaps a genuine sign of waning enthusiasm in a man of whom the Cincinnati Enquirer had once said, “When that player quits baseball, boys will refuse to eat mince pies.”18

The little Scottish outfielder Nicol was disliked by many of his teammates, but he had been the subject of a flattering story in the Enquirer praising his skill at sacrifice hitting which Reilly, free-swinger that he was, took as a reflection on himself. A clubhouse argument with Nicol escalated into a wrestling match. This embarrassing but relatively minor episode attracted press attention when the two players made up their differences to combine in a brief strike on August 4 in protest against the fines taken out of their pay checks, and also because of the incongruous picture of a fight between the elongated Reilly and Nicol, who was one of the smallest players in the game but a very skilled wrestler. Ironically, when Nicol first joined the Reds, the Commercial Gazette had jokingly suggested a Nicol-Reilly wrestling match, “catch-as-catch-can – all holds below the knee barred.”19

For much of the season, the entire Reds team fought with umpire Doescher whenever he worked their games. Relations between Doescher and the players became so bad that the umpire even hit Bid McPhee, known for never having suffered a fine during the course of his long career, with a substantial assessment. For some reason, however, Doescher never sent the Association office an official notice of his fine on McPhee, thereby keeping the second baseman’s record officially clean.20 Reilly did not escape so easily on July 12, when Doescher called him out on close plays at home plate in the first inning and again in the ninth during a 2-1 loss to Cleveland. The claim was made that during an earlier game at Philadelphia, Athletics manager Billy Sharsig had informed Doescher that Reilly had asked him, “How much are you paying this man [Doescher] for these games?” Doescher allegedly had it in for Reilly after that.21

After 1888, Reilly’s hitting began a slow decline that turned into a precipitous drop in 1891, when he batted .242 for a seventh place Cincinnati team racked by dissension. Following that season, the Reds brought in Reilly’s long-time rival Charlie Comiskey to play first base and manage. There had been some talk of moving Reilly to the outfield, but Comiskey seems to have vetoed that move, ending Reilly’s career as a Red. He chose to retire from baseball and never returned to the game.

Although he was now 33 and coming off his worst performance since his rookie season eleven years before, Reilly still had options that would have allowed him to continue his major league career. During the winter there were reports he was negotiating with the New York Giants, but nothing came of this.

The most intriguing possibility, however — although no one could have fully appreciated this at the time — came in early May 1892. When veteran outfielder Ned Hanlon, just released by Pittsburgh to take over as manager of the perennially downtrodden Baltimore club, came to meet his new club in Cincinnati, his first move was to make an offer to John Reilly to become Baltimore’s first baseman. After several days of indecision, Reilly turned down the opportunity to become the first building block in the famous Oriole team that would dominate the National League during the mid-1890s.22 The fact that Hanlon made this offer suggests that Reilly still had plenty of baseball left in him; not simply because it was a legitimate offer, but because in the course of building his powerhouse Orioles club Hanlon would become famous for his unerring touch in determining whether a veteran player’s usefulness was at an end.

When Reilly was considering Hanlon’s offer, he told the Enquirer that, much as he loved playing baseball, he could do so only at a substantial financial sacrifice, since his current work for the Strobridge lithography firm had been earning him at least $50 every week since the season ended, and sometimes as much as $80 (presumably due to overtime). These were substantial sums in a day when an ordinary skilled or semi-skilled laborer thought he had had a good year if he earned $500.

Reilly may well have been exaggerating his earnings a bit to improve his bargaining position, yet there can be no doubt that the essential factor in Reilly’s decision to retire was his alternate career as a commercial artist, which he had continued to follow during off-seasons after returning home from New York in 1883. It is not clear, in fact, that at any time during his life Reilly ever regarded his art merely as a job providing off-season cash but of secondary interest to his baseball career. In fact, he would later tell Elizabeth Kellogg of the Cincinnati Art Museum that his decision to go to New York had been motivated not by baseball considerations, but rather by advice from Strobridge’s star lithographer Matt Morgan, who had told Reilly that joining Strobridge’s New York office would be a good move for his artistic career.23

The Strobridge Company was exceptionally successful during the 1880s, and the earning power of major league baseball players did not by any means dwarf that of Strobridge artists. In fact, contracts surviving in the Cincinnati Historical Society suggest that artists out-earned ball players: weekly salaries as high as $65 for artists were not unusual. Matt Morgan got $200 per week, over $10,000 on a yearly basis and far more than any contemporary baseball player ever received. As a new apprentice in 1873, the young Reilly received only $2.50 per week, a sum that went up by a dollar a week for each year of his four-year apprenticeship. By the early 1880s, Reilly was receiving $20 per week as a professional artist, a very comfortable income for the day. His later contracts do not survive, but artists making less than Reilly in the early part of the decade were paid forty to sixty dollars weekly by the later 1880s.

As it happens, the Reds’ salary records for much of the 1880s also survive in the Cincinnati Historical Society’s archives. They reveal that, as a result of the bidding war between New York and Cincinnati for his services, Reilly’s salary when he joined the club in 1883 was $1,800, more than any other player on the team, even veterans Will White and Charlie Snyder, established stars who were the club’s primary battery and the heart of the team. For several years Reilly’s pay then remained the same while others on the team outstripped him. In the latter part of the decade he seems to have become a more stubborn negotiator, especially after the departure of manager O.P. Caylor, with whom he appears always to have been on good terms. By 1887 he was getting $2,200. His pay in later years is not known, but at the time of his retirement Reilly’s earnings as an artist were undoubtedly still less than the Reds had paid him in recent seasons, for bitter interleague trade wars in 1890 and 1891 had pushed baseball salaries up dramatically. The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette on October 4, 1890, described Reilly’s salary demands as only “a little less exorbitant” than the $16,000, three-year contract that future Hall of Famer Bid McPhee was asking.

Of course, Strobridge artists did not enjoy the players’ advantage of being able to earn these substantial sums with short workdays and seven-month playing seasons; then again, the shrewd and level-headed Reilly must have understood that, whatever the attractions of baseball, a player’s vulnerability to age and injury made his career an insecure and short-lived one, and that he would be well-advised to make the most of his more durable artistic talents. By December 1892, when Cincinnati released Reilly, the baseball wars had come to an end and salaries were inevitably going to drop drastically. With Reilly clearly past his peak years, his decision to retire and pursue his artistic career full-time makes perfect sense.

Reilly had an additional reason for staying in Cincinnati: his comfortable and inexpensive living arrangements in his hometown. He never married and continued to live with his mother’s family. Her second husband probably died about 1880, for he disappears from the city directories at that time and Reilly’s mother began to be listed as Mrs. Helen Schafer. The family soon moved east to Columbus Tusculum, now a neighborhood in the middle of Cincinnati’s east side but then a rather distant suburb along the river. Reilly would remain in this home until he died on May 31, 1937, after an illness of several years. In his last years his home was maintained by a niece, who shared the house with Reilly and her husband. He was survived by his brothers Frank, an undertaker in Cincinnati, and Charles, who lived in Chicago.24

Reilly continued to work for Strobridge until the early 1930s, specializing in circus posters. This was a particular staple of the firm’s business, especially after the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey circuses merged to become the country’s dominant circus and gave Strobridge all their poster business.

Although Reilly made his living as a commercial artist, on his own time he liked to paint nature scenes copied from his wanderings in local woods or on the shores of the Ohio River. In a short reminiscence, Elizabeth Kellogg, who worked at the Cincinnati Art Museum, recalled that “just once, for he was a modest soul,” Reilly put his paintings on exhibition. Kellogg and a friend who worked at the Cincinnati Art Museum were surprised to see such delicate workmanship from the hands of a man who was large even for a professional athlete. Each of them bought a sketch, and Reilly, having heard that two women from the Art Museum had bought his work, came by and dropped off a large watercolor for each to show his appreciation. Kellogg gave hers to her brother, who was “among the devout worshippers of the famous first baseman.” Perhaps her willingness to pass along the gift may hint that she was not truly enamored of Reilly’s painting, but it certainly does show the durability of his reputation as a player even decades after his retirement, for Kellogg did not go to work for the Art Museum until 1909, nearly twenty years after Reilly had ended his career with the Reds.25

Although Reilly was not a really great player, his local connections and his strong character and vivid personality made him the most popular player of his generation in Cincinnati. During his playing days, a local tobacconist had named a brand of cigars the “Long John Reilly.”26 As Elizabeth Kellogg’s reminiscences show, he remained something of a minor celebrity around town, and his name continued to appear occasionally in the newspapers as a former baseball luminary. For example, a decade after Reilly’s retirement the Enquirer described another Cincinnatian who had enjoyed a cup of coffee in the major leagues as “an old-time ball player, who was at the height of his popularity when ‘Long John’ Riley was playing ball.” Reilly was also known as a leading spirit of the Cincinnati Art Club and as the senior member of his Masonic lodge. The tenor of his obituaries, especially the one from the Enquirer quoted above, show that in his later years he must have continued to charm newspaper reporters with his stories and observations.27

He may not have been above pulling a reporter’s leg, either, for his Times-Star obituary stated that during his playing days Reilly had developed into a competent pitcher, under the tutelage of Louisville’s star hurler Tom Ramsey, and pitched about 20 games for the Reds. None of this was true.28 More than ten years after his death he still remained a name to mention in his home town, for in 1948 the Times-Star announced news “of special interest to baseball fans” when it was reported that the home at Columbia Parkway and Stanley Avenue in which John Reilly had spent most of his life had been sold to make way for a gas station, and the house itself would be moved to an empty lot farther up Stanley Avenue.29

Sources

Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, 1882-1891, passim

Cincinnati Gazette, 1880, passim

Cincinnati Enquirer, February 14 and 19, 1862, and 1880-1891, passim; June 1, 1937.

“Cincinnati Reds” collection, Cincinnati Historical Society archives.

Cincinnati Times Star, 1885-1981, passim; May 11, 1927; June 1-2, 1937; January 16 and May 28, 1948.

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland. Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 1987. Page 157.

“Long John Reilly: First Baseman and Artist,” in “Elizabeth A. Kellogg Collection,” Cincinnati Historical Society Archives.

New York Clipper, 1882, passim

“Strobridge Lithography Company” collection, Cincinnati Historical Society archives.

Tucker, Spencer. Andrew Foote: Civil War Admiral on Western Waters. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001. Page 156

Notes

1 Cincinnati Enquirer, February 16 and 19, 1862. Fuller details are given in B. Cooling, Forts Henry and Donelson, p. 157 and S. Tucker, Andrew Foote, p. 156.

2 Strobridge Lithography Company collection, Cincinnati Historical Society archives.; Cincinnati Times Star, June 1, 1937.

3 Cincinnati Times-Star, June 2, 1937.

4 Cincinnati Commercial, May 19, 1880.

5 Cincinnati Commercial, May 19, 1880.

6 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 18, 1880.

7 New York Clipper, March 10, 1883.

8 See especially Cincinnati Commercial, October 29, November 25-26 and 29, 1882; New York Clipper, December 2, 1882; Cincinnati Enquirer, December 10, 1882)

9 Cincinnati Times Star, May 11, 1927 and June 2, 1937.

10 Quoted in Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, May 13, 1886.

11Cincinnati Enquirer, June 1, 1937.

12 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 27, 1890.

13 Cincinnati Times-Star, January 11, 1890.

14 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 28, 1885.

15 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 28, 1889.

16 Cincinnati Times-Star, January 11, 1890.

17 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 31, 1886.

18 Cincinnati Enquirer, November 5, 1882. For his talk of quitting the game, see for example Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, November 4, 1888.

19 Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, January 9, 1887.

20 Cincinnati Times-Star, September 1, 1888; Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, October 28, 1888.

21Cincinnati Enquirer and Commercial Gazette, July 13, 1888.

22 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 9, 1892 and following days.

23 “Long John Reilly: First Baseman and Artist,” in “Elizabeth A. Kellogg Collection,” Cincinnati Historical Society Archives.

24 Cincinnati Times Star, June 1, 1937.

25 “Long John Reilly: First Baseman and Artist,” in “Elizabeth A. Kellogg Collection,” Cincinnati Historical Society Archives.

26 Cincinnati Enquirer, February 17, 1889, and Cincinnati Times Star, February 22, 1889.

27 Quotation from the Cincinnati Enquirer, November 19, 1902; the misspelling of the name is not unusual.

28 Cincinnati Times-Star, June 2, 1937.

29 Cincinnati Times Star, January 16, 1948; May 28, 1948.

Full Name

John Good Reilly

Born

October 5, 1858 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

May 31, 1937 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.