Doc Oberlander

After the lefty pitched three games for the 1888 Cleveland Blues, Syracuse-educated Doc Oberlander found his way out west as a federally appointed subagent and physician with the Crow (Apsáalooke) tribe in southeast Montana, and the superintendent of Pryor Creek Boarding School.

After the lefty pitched three games for the 1888 Cleveland Blues, Syracuse-educated Doc Oberlander found his way out west as a federally appointed subagent and physician with the Crow (Apsáalooke) tribe in southeast Montana, and the superintendent of Pryor Creek Boarding School.

Hartman Louis Oberlander was born May 12, 1864, along the western shore of Lake Michigan in Waukegan, Illinois. He was the fourth son of a prominent German Lutheran minister, Reverend Alexander and his wife Mathilda, who mothered 14 children. By 1880, the then family of thirteen moved to the Onondaga Valley in upstate New York, the Reverend Oberlander founding the Mount Tabor Lutheran Church in Syracuse, and four years later the Zion Lutheran Church. At the time of his death, Alexander Oberlander was the oldest German clergyman in Syracuse.

Hart Oberlander, as he was known at the outset of his playing days, was an outfielder in his youth who wouldn’t begin pitching until 1887. His first year in the professional ranks came two years earlier with his hometown Stars in the New York State League at age 21. Rumors of his imminent release percolated by July, but when he broke his left leg attempting to steal second in a late September contest, Sporting Life called him “one of the best men on the nine.”1

One of only two native Syracusans with the Stars in his sophomore season, he batted .232 in 76 games, including a home run on May 24. On August 7, Oberlander appeared on the same diamond as Wyman Andrus, Canadian shortstop for Hamilton. Both men would eventually end up as physicians in Montana, practicing two hours apart.

Dr. Hartman Oberlander graduated from Syracuse University in the spring of 1887.2 1887 was also Doc Oberlander’s first season in the box, pitching 24 games for the Scranton Miners. He walked 84 batters, beaned another 21 while heaving 42 wild pitches, but held a respectable 2.37 ERA, good for fourth in the International League.3 “Oby made his debut as a pitcher against the Hamiltons, holding them down to four hits and striking out ten men.”4 He added an August 13 round-tripper off Pete Wood. Based on his Scranton season, two scouts recommended Oberlander to Cleveland in early October.5

Oberlander’s subsequent signing with Cleveland was the subject of a remembrance of sorts in the Washington Herald during the winter of 1911. “Some day … some baseball historian will write the ‘False Alarm’ chapter of the book: the story of prospective players who have promised much, but paid little; the men whose services were supposed to be indispensable to the life of the game, but who failed to survive the ordeal to which all recruits in the major league ranks are subjected.”6 When Cleveland needed a pitcher in 1887, “Doc Oberlander, a southpaw, possessing … a curious curve,”7 was recommended to the club, and “in baseball as in everything else, the great secret of success was to keep your employers on the anxious seat.” So Oberlander vamoosed, leading the Cleveland scout, Frank H. Brunell8 on a long chase for his left-handed signature. As the story goes, Brunell, at the insistence of team captain Jay Faatz, went from Cleveland to Pittsburgh, then to Wheeling, Huntington, Harrisburg, York, Baltimore, Richmond, Washington, Scranton, Binghampton, Elmira, Utica, and finally Cooperstown. “For ten days and ten nights, Mr. Brunell was just about one day behind his quarry. In the Fennimore Hotel at Cooperstown Mr. Brunell finally found his man.”9 Once discovered, per this Herald telling, the prospect demanded $500 more than the contract Brunell offered. The team approved. The Blues spent $1,500 — in both expenses and salary offered — before Oberlander boarded a train to Cleveland.

After joining the team, Oberlander appeared in at least two postseason exhibition games. Versus Indianapolis on October 13, he took a 6-1 loss.10 Four days later he started against Cincinnati, exiting the game with a 5-3 lead after pitching four innings.11 In November 1887, Sporting Life reported of his Cleveland test, “In the games he has played Oberlander showed up finely, and [Pop] Snyder thinks he will make a great pitcher next season. He has the [Toad] Ramsey wind drop to a nicety, and will seek control of the ball this winter.”12

During the 1888 preseason, praise was piled on Cleveland’s only lefty pitcher: “Dr. Oberlander, of the Clevelands, is getting into fine condition for his season’s work. ‘Oby’ has discovered a new ‘razzle’ ball.”13 On a cold and clear day with 800 Cleveland cranks in the stands, Oberlander made his debut on May 16 against the Bridegrooms of Brooklyn. The home team plated three runs of support in the top of the first inning14 before Oberlander strode to the box in his white home flannels with an old English “C” in blue on the left breast, navy blue stockings and belt, and a cap of white and blue stripes. Oberlander proceeded to walk the leadoff batter, George Pinkney, who took third on a wild pitch. After the first out, Doc walked Dave Orr, who took second, and Pickney scored on a second wild pitch. Oberlander recorded his first career strikeout courtesy of Darby O’Brien, but his batterymate, Pop Snyder, muffed the catch and O’Brien got second on the passed ball. After a sacrifice fly scored another run, a comebacker to the mound retired an eventful side.15 Cleveland failed to score in the top of the second. Oberlander walked the first two batters in the bottom of the inning. After a fly out to center and another base on balls, the bases were loaded. Two errors, a wild throw, and a base hit kept the Bridegrooms circling the bases, and the second concluded with Brooklyn ahead, 7-3. In the third, for the third inning in a row, Oberlander walked the leadoff batter. After his left fielder dropped a fly ball, and Oberlander walked another batter, both advanced on his third wild pitch in as many innings. A pop to the middle infield stopped the bleeding. Oberlander and the Blues retired the Bridegrooms in order in the fourth, and after the teams traded blows for a couple innings, Oberlander gave up a three-run homer to Dave Foutz which proved the difference in the 12-9 Brooklyn victory. Oberlander gave up only six hits, but his wildness factored heavily, as did Cleveland’s 16 errors, while earned runs favored the Blues, 6-4.16

Ten days later, “Oberlander’s effective pitching”17 helped Cleveland win its first game from Charles Comiskey and the St. Louis Browns. Oberlander, working with Mike Goodfellow, got the complete game victory. He struck out seven, walked none, and was aided by an 8-2-5 twin killing. “Oberlander was hard to overcome.”18

Oberlander got one more chance in his big-league finale on June 2 versus Kansas City. Pitching to his third catcher, Chief Zimmer, he held the Cowboys to six hits with eight strikeouts, and Cleveland led 15-9 going into the ninth. “Indifferent fielding caused by overconfidence”19 allowed Kansas City to plate seven, walking off on the young lefty with two out in the ninth. F.H. Brunell for Sporting Life, “Our medical south-paw phenomenon, Dr. Oberlander … wasn’t killed Saturday, but rather committed suicide with two men out, seven hits, for twelve bases, and a base on balls, earned seven runs and the game … Oberlander will be tried again, I suppose. He has wonderful balls, but isn’t made of the right kind of stuff. His strength is fleeting, and he is slow and awkward in the box, and hasn’t enough courage to stand him in tight places.”20 The Cleveland Plain Dealer wasn’t so sure, “Oberlander’s work ought to earn him a speedy release. He lost head, heart, sense and speed.”21

By all accounts Oberlander possessed a drop ball, or overhand curve,22 of some regard, but no means of reining it in. He walked 18 in 25 2/3 innings with the big club — adding five wild pitches and a hit batsman. But he must have had something on the ball, as he managed to strike out 23 American Association batters, which, if he would have played a full season, translated to 261 strikeouts — more than every other pitcher, save Ed Seward. But conjecture aside, Oberlander eked out a single victory while backed by suspect fielding during his otherwise tumultuous cup of coffee with fast company. He also had some success at the dish, scoring on each of his three hits which included two doubles and four RBIs.

Released to Toronto, Oberlander played some games in the garden in addition to slab work, clubbing a home run on July 17 off Albany’s Frank “Monkey” Foreman. At the end of the month he nearly blanked Hamilton before surrendering a solo shot to opposing pitcher Pete Wood. “Oberlander’s work has proved eminently satisfactory. He has pitched in four games and won them all.”23 In a letter from ‘G. Whiz’ recalling Syracuse’s 1888 championship over Toronto, “Hartman Oberlander, of this city, who was at that time the Toronto’s best pitcher was in the box against the Stars, and up to the seventh inning the home team had not found him for a run, and the game was apparently lost. In this inning, the great and only ‘Lefty’ Marr stepped to the plate, and, meeting one of ‘Oby’s’ speedy ones right on the trade mark for three bases, drove the first nail into Toronto’s coffin. The game was won at this point, as Ollie Beard walked up to the line and calling out to ‘Oby,’ said, ‘Oby, there’s your father up in the grand stand looking at you.’ This remark together with the unearthly din of tin horns from Manager [Charlie] Hackett’s brigade of small boys (2,000 strong), had the desired effect, and every ball that ‘Oby’ pitched for some time thereafter seemed to go safe from the bat when hit.”24 By September 5, Toronto had released Oberlander.

Around May 22, 1889, Oberlander was signed back with Syracuse by manager Jack “Death to Flying Things” Chapman. A week later, Oberlander went the distance scattering six Hamilton hits while striking out five. It was a performance he would oft repeat as he posted an ERA a skosh above one. On Independence Day weekend in Syracuse, Oberlander pitched the second game of a doubleheader against London when in the tenth inning he was again badly hurt sliding into second. Two responding physicians pronounced Doc unable to play. John Keefe was summoned to replace Oberlander, but London refused to continue and the game was forfeited to Syracuse by Umpire Hoover. At the end of July, versus his old club, Toronto, Oberlander shut out the Canucks allowing just two singles. His batterymate on the day was Moses Fleetwood Walker.25

Recognized at season’s close in Sporting Life as the International League’s top pitcher, Oberlander finished out the 1889 campaign with Auburn of the New York State League. “His excellent work in the box was the direct cause of the Auburn team winning the State League pennant,”26 which Sporting Life described as, “one of Spalding’s best. It is white, with a blue border and the words, ‘State League Champions 1890’, in blue letters.”27

The following winter, “Hartman Oberlander, the ex-pitcher, hung out his ‘shingle’ as M.D. on Butternet street [in Syracuse].”28 The ballfields were still calling, but he lasted only a month with the Newark Little Giants before being given his unconditional release by manager Sam Trott, “his work [being] unsatisfactory.”29 He caught on with Olean, but only briefly.

Three years out of medical school, Doc Oberlander probably figured it was time to turn the page. In June, accompanied by his father, the young doctor endeavored on a two-month trip to Europe to the Berlin Congress of Physicians and Surgeons to obtain his supply of instruments, and “to teach some of his friends there the science of catching and throwing a base ball.”30 It was also during 1890 that Oberlander married his English-born wife, Jannis (Jennie Possehl). Their union produced three children, Lillian A., Arthur A, and Fredolin — named for Hartman’s younger brother, who, like their father, was a Lutheran minister.

After two years of private practice in Syracuse and Jamesville, Oberlander was appointed physician at the Eastern Cherokee School and Agency in North Carolina in 1893. Six years later, in a story that is torn and mostly missing from LA84 Foundation’s copy of Sporting Life, the reader is informed that Dr. Hartman Oberlander is the government physician at Cherokee, North Carolina, where he organized a ball team, “Dr. Oberlander’s warriors.”31

In early 1902, Dr. Oberlander was appointed physician with the Crow in Montana, and named the first superintendent of the newly constructed Pryor Creek Boarding School when it opened February 12, 1903.

Superintendent Oberlander’s entry for the Report of the Department of the Interior, dated August 10, 1905, states that with an average attendance of 57 students ages 6-16, “The results of the year’s work prove that Indian children are the equals of their white brothers and sisters in their intellectual pursuits.”32

Thirteen years later in the Annual Report to the Board of Indian Commissioners, Malcom McDowell wrote to Chairman George Vaux Jr., “The health of the Pryor Creek Crows is under the charge of Dr. H.L. Oberlander, who is subagent and physician. He is one of the most efficient men I have met in the Indian Service, for in addition to his manifold duties as subagent, physician, farmer, and general factotum, he is a power for good along social-service lines. Pryor Creek Indians, almost all of them full bloods, seemed to me to be the most progressive on the reservation, and this is largely due, I am sure, to the indefatigable labors and kindly tact of Dr. Oberlander.”33

At eight o’clock in the evening on November 16, 1922, Dr. Oberlander died of heart trouble at Pryor, Montana, and was buried twenty miles away in neighboring Rockvale, just off the reservation that he had made his home and professional endeavor for nearly twenty years.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend special thanks to Skylar Browning for his many splendid contributions to this biography. This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

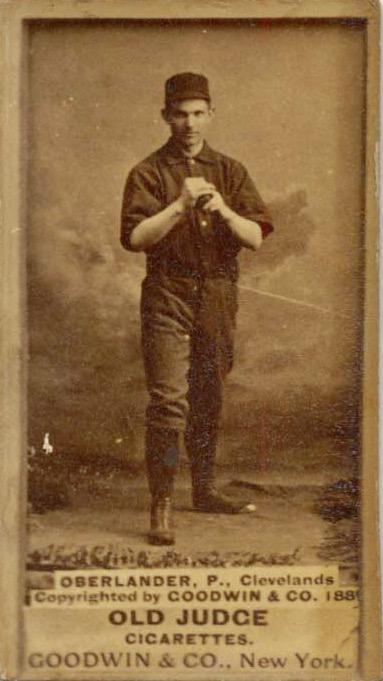

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on online newspaper archives including The Sporting Life, as well as the Chronicling America newspapers hosted by the Library of Congress, including the Anaconda Standard, Butte Inter-Mountain, Evening World, Great Falls Tribune, Helena Independent, Indianapolis Journal, Missoulian, Washington Herald, as well as the online archives of the Montana Historical Society, and finally, the online edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The author’s book with fellow SABR member, Skylar Browning, Montana Baseball History, was partially excerpted. Additional information was verified in the player’s file at the Hall of Fame Museum and Library in Cooperstown. Census data was acquired from familysearch.org. Photograph is courtesy of the Eric Angyal collection.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, September 30, 1885

2 “The Syracuse University Commencement,” Northern Christian Advocate, June 30, 1887.

3 Sporting Life, November 9, 1887

4 Sporting Life, July 18, 1888

5 Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 7, 1887.

6 Washington Herald, January 2, 1911

7 Ibid.

8 At the time, Brunell was sports editor of the Plain Dealer, and in 1893 sporting editor of the Chicago Tribune. A pioneer horseracing handicapper and founder of the Daily Racing Form, and later Secretary of the American Brotherhood and Players’ League. Frank H. Brunell died November 16, 1933.

9 Washington Herald, January 2, 1911

10 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 23, 1887

11 Cleveland Leader, October 18, 1887.

12 Sporting Life, November 2, 1887

13 Sporting Life, February 29, 1888

14 It was commonplace up until at least 1892 for the home team to bat first, as the ball was livelier and easier to see in the early goings.

15 “A Hard Game to Lose,” Cleveland Leader, May 17, 1888.

16 Evening World, May 16, 1888

17 Sporting Life, June 6, 1888

18 Indianapolis Journal, May 27, 1888

19 Sporting Life, June 13, 1888

20 Sporting Life, June 13, 1888

21 “An Awful Finish,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 3, 1888.

22 James, Bill and Neyer, Rob. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (Touchstone 2004), 16-17.

23 Sporting Life, July 18, 1888

24 Sporting Life, March 30, 1895

25 Sporting Life, August 21, 1889

26 Sporting Life, December 25, 1889

27 Sporting Life, November 20, 1889

28 Sporting Life, January 10, 1890

29 Sporting Life, May 24, 1890

30 Sporting Life, November 22, 1890

31 Sporting Life, March 4, 1899

32 Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended 1905, H.L. Oberlander Superintendent and Physician Pryor Creek School, 240.

33 Reports to the Department of the Interior For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1918, Volume II, Indian Affairs Territories, Malcolm McDowell, 373.

Full Name

Hartman Louis Oberlander

Born

May 12, 1864 at Waukegan, IL (USA)

Died

November 14, 1922 at Pryor, MT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.