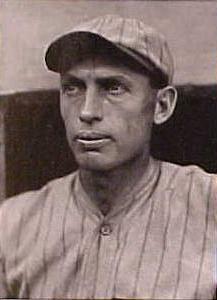

Dode Paskert

Fleet-footed Dode Paskert was one of the finest defensive center fielders of the Deadball Era. “It is no exaggeration to say that Paskert is one of the greatest judges of a fly ball in the game today,” wrote Baseball Magazine‘s J. C. Kofoed in 1915. “Those who have seem him circle, hawk-like, turn his back and speed outward, and then make a daring leap, with the spoiling of a three-bagger at the end of it, know how true that statement is.” As for his offense, Paskert was an extremely patient hitter who worked pitchers deep into the count, often ranking among the National League leaders in both walks and strikeouts. A pronounced pull hitter, he choked up on the bat and found his hits by punching the ball into left field. Though used most often in the leadoff position, Paskert frequently hit for extra bases; from 1912 to 1918 he ranked among the NL’s top ten in doubles four times and home runs once.

Fleet-footed Dode Paskert was one of the finest defensive center fielders of the Deadball Era. “It is no exaggeration to say that Paskert is one of the greatest judges of a fly ball in the game today,” wrote Baseball Magazine‘s J. C. Kofoed in 1915. “Those who have seem him circle, hawk-like, turn his back and speed outward, and then make a daring leap, with the spoiling of a three-bagger at the end of it, know how true that statement is.” As for his offense, Paskert was an extremely patient hitter who worked pitchers deep into the count, often ranking among the National League leaders in both walks and strikeouts. A pronounced pull hitter, he choked up on the bat and found his hits by punching the ball into left field. Though used most often in the leadoff position, Paskert frequently hit for extra bases; from 1912 to 1918 he ranked among the NL’s top ten in doubles four times and home runs once.

George Henry Paskert was born in Cleveland on August 28, 1881, the oldest of three children of Matilda Radermacher and Bernard Paskert, a railroad flagman. The grandson of Dutch immigrants, George completed two years of high school before finding work as a machinist’s apprentice. He was still working in that profession in 1904 when a traveling salesman saw him pitch for a semipro club in Warren, Ohio, and recommended him and a teammate, future major leaguer Jimmy Austin, to Dayton of the Central League. Quickly converted to the outfield, Paskert spent three seasons with Dayton before moving on to Atlanta, where he batted .290, led the Southern Association in stolen bases, and helped the team to the 1907 championship. Two weeks before the end of the season, the Cincinnati Reds purchased his contract. Paskert was already 26 years old, though few knew it at the time. For several years into his major league career, his birth year was incorrectly reported as 1886, leading contemporaries to believe he was a full five years younger than his true age.

The precise origin of Paskert’s nickname (an early 20th century moniker also applied at various times to Joe “Dode” Birmingham and Pete “Dode” Alexander) has been lost to history, but more than likely it was a dig at his perceived low intelligence. The English Dialect Dictionary, published in 1900, describes a “dode” as a “slow [witted] person,” and a scattering of press accounts confirm that Paskert was considered stupid. In 1911, for example, Baseball Magazine‘s W. A. Phelon grouped Paskert with fellow center fielder Johnny Bates in that regard. “Certain critics declare that there is no choice between Bates and Paskert when it comes to intelligence,” Phelon wrote, “that both of them are crowned with domes of elephant-tusk, and that if either of them ever thought quickly it must have been when deciding whether to take beer or ginger ale.” Whatever its origin, the nickname apparently didn’t bother Paskert, who often included the “Dode” in his signature.

A second nickname, “Honey Boy,” was more complimentary. So named because he was “such a sweet ballplayer,” the 5’11”, 165 lb. center fielder impressed observers from the start with his speed and superior range, though his offensive skills took longer to mature. After posting on-base percentages of .298 and .327 in 1908 and 1909, respectively, Paskert enjoyed a breakout season in 1910, when he paced all NL outfielders in putouts and finished third in the league with 51 stolen bases. Most impressively, he batted .300 and led the Reds with a .389 on-base percentage. But despite that performance, Cincinnati failed to finish in the first division for the third time in four years, a disappointment that convinced manager Clark Griffith to overhaul his roster. The following February, the Reds shipped Paskert to the Phillies, along with teammates Fred Beebe, Jack Rowan, and Hans Lobert, in exchange for Johnny Bates, Eddie Grant, George McQuillan, and Lew Moren. Cincinnati soon regretted the trade, as Paskert proved to be by far the most valuable of the eight players in the deal.

On April 13, 1911, in just his second game with his new club, Honey Boy made one of the most memorable catches of the Deadball Era. In the bottom of the eighth inning, Fred Snodgrass of the Giants smashed a deep line drive into the left-center field gap at the Polo Grounds. It looked like a sure home run, but Paskert raced after the drive and at the last moment turned, dove parallel to the ground, and speared the ball with his bare hand. Years later, such experienced observers as sportswriters Fred Lieb and Jim Nasium and Phillies left fielder Sherry Magee still considered it the greatest catch they had ever seen. It was also one of the last ever made at the original Polo Grounds structure built in 1890. The day after the game, the wooden park burned to the ground and was replaced two months later by the steel-and-concrete edifice that hosted the Giants for the next 46 years.

Paskert brought more to the Phillies than his fielding. In 1912 he enjoyed the best offensive season of his career, posting career highs in batting average (.315), on-base percentage (.420), and slugging percentage (.413). Though he never replicated that standout season, Paskert remained an integral part of the Philadelphia attack for several years, finishing in the league’s top ten in runs scored three times from 1913 to 1917.

In an era when most players faded quickly after their primes, Dode impressed observers with his consistent, durable play in the face of advancing age. “Time does not dim him,” wrote The Sporting News. “His arm is as dangerous to a base runner as ever and his hitting eye does not seem to have lost any of its keenness.” Jim Nasium added, “The remarkable thing about Paskert at 36 years of age is that he has lost none of the use of his legs, and is still able to pull down the hits or circle the bases at full speed without even breathing hard. He is never even attacked by charley horse, never suffers from sprained tendons, and never had to tape his legs as a result of the strain of continual service.” Nasium concluded that Paskert as a fielder was still “better than [Tris] Speaker in going to his left” and better than Ty Cobb “in any direction.”

Such high praise undoubtedly helped persuade the Chicago Cubs to trade their young slugger Cy Williams for Paskert following the 1917 season. The deal was one of the first of many short-sighted exchanged in Cubs history: Williams spent the next 13 seasons in Philadelphia, winning three home-run crowns, while Dode’s days as an effective major leaguer were numbered. Over the next couple years, he continued to impress with his play in center field, but age and nagging injuries to his wrist and back finally began to slow his bat. In 1919 Paskert batted a miserable .196, and though he rebounded to hit .279 in 1920, that offseason the Cubs sold him to Cincinnati for the waiver price. Back where he had started his major league career 14 years earlier, he collected only 16 hits in 92 at-bats before drawing his release.

Shortly before leaving the major league scene, Paskert was hailed as a hero for his actions in rescuing three families from an early morning fire. According to newspaper reports, Paskert and a friend were walking home at 1:30 a.m. on February 23, 1921, when they spotted the blaze, which broke out in a Cleveland clothing store before spreading to nearby apartments. While his friend pulled the alarm, Paskert made three separate trips up the burning stairwell, carrying out five children and directing their parents to safety, saving the lives of 15 people. “In rescuing the families,” the Cleveland Plain-Dealer reported, “Paskert’s hands and arms were burned badly and his face blistered by the flames.”

Even past 40, Paskert refused to retire. “I thoroughly like baseball,” he once said. “I like baseball from the first day of spring to the last day before winter sets in.” Over the next six years Dode traveled the country as an itinerant minor leaguer with Kansas City and Columbus in the American Association, Atlanta and Nashville of the Southern Association, and Erie of the Ohio-Penn League before finally leaving the game at age 46 after the 1927 season. He then returned to Cleveland where he lived with his wife, Emily Belle DeKalb (whom he had married in 1902), and their one son. Paskert worked as an inspector for the Gabriel Snubber Company. Surviving his wife by five years, he passed away on February 12, 1959, after suffering a stroke. Paskert is buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery in Cleveland.

Last revised: September 7, 2020 (ghw)

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

George Henry Paskert

Born

August 28, 1881 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

February 12, 1959 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.