Roger McKee

With his one major-league hit, Roger Hornsby McKee never came close to his namesake’s Hall of Fame total. He did, though, channel Rogers Hornsby with an Organized Baseball batting title.1 And while the namesake Hornsby was a player-manager for 12 seasons during an era when such skippers had a penchant for giving themselves a turn on the mound from time to time,2 he resisted the temptation to pitch. Named for the second baseman, Roger McKee was a major-league pitcher and became the youngest player in the modern era to notch a nine-inning complete-game win – just after he turned 17. Although this accomplishment is not recognized as an official record, given twenty-first-century trends in the usage of pitchers and the minuscule number of complete games by starters, however, it may well be a distinction that will remain Roger McKee’s as long as professional baseball is played.

With his one major-league hit, Roger Hornsby McKee never came close to his namesake’s Hall of Fame total. He did, though, channel Rogers Hornsby with an Organized Baseball batting title.1 And while the namesake Hornsby was a player-manager for 12 seasons during an era when such skippers had a penchant for giving themselves a turn on the mound from time to time,2 he resisted the temptation to pitch. Named for the second baseman, Roger McKee was a major-league pitcher and became the youngest player in the modern era to notch a nine-inning complete-game win – just after he turned 17. Although this accomplishment is not recognized as an official record, given twenty-first-century trends in the usage of pitchers and the minuscule number of complete games by starters, however, it may well be a distinction that will remain Roger McKee’s as long as professional baseball is played.

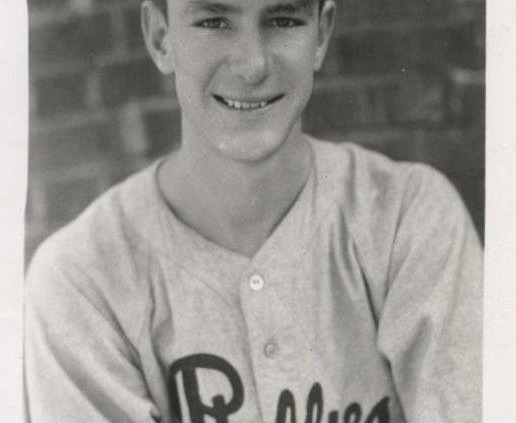

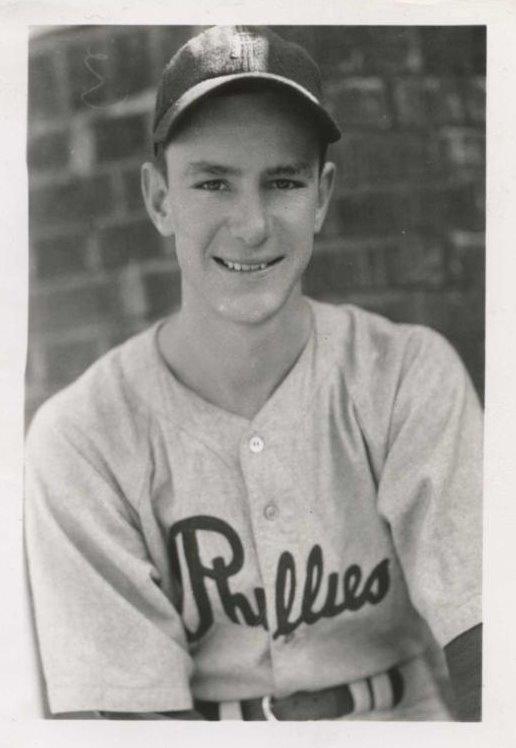

Signed by the Philadelphia Phillies as a left-handed North Carolina high-school and American Legion pitching phenom in the midsummer of 1943, McKee stayed with the big club through the end of that season and hurled his complete-game win on October 3. He got his first minor-league experience in 1944, with a brief late-season recall to Philadelphia before a year-plus of military service in 1945-46. Then, his pitching velocity diminished by what he attributed to throwing too hard, too soon, in a shortened, cold and wet 1944 spring training, he began an odyssey through the minor leagues as a first baseman and occasional outfielder before returning home with his family to work for the Postal Service, coach baseball, commit himself to civic affairs, and live a rich, full life with his spouse of 70 years.

Roger Hornsby McKee was born on September 16, 1926, in Shelby, Cleveland County, North Carolina, the eldest child of Broadus Lee McKee and Gertie Spencer McKee. Broadus McKee’s ancestry was Scots-Irish; Gertie Spencer’s was English, and they and their parents were all native North Carolinians. Located 40 miles west of Charlotte in the North Carolina Piedmont region, by 1926 Shelby was a textile-mill town with a burgeoning population due to New South industrialization.3 Broadus McKee worked in the LeGrand family’s Shelby Mill cotton factory and later as a fireman for the City of Shelby. Gertie tended the McKee home and also worked at Shelby Mill. The family – by 1940 it included Broadus, Gertie, Roger, a younger son, Bill, and two younger sisters, Elissa and Margie – lived in the mill village, on-site housing provided by Shelby Mill.4

Broadus McKee was an avid fan of baseball, and especially followed the St. Louis Cardinals and their player-manager, Rogers Hornsby.5 On September 16, 1926, when Broadus and Gertie welcomed their first-born, the Cardinals closed the day’s play tied with the Cincinnati Reds for the National League lead. By October 2, when the Cardinals had eked out the pennant with a two-game edge on the Reds and opened the World Series against the Yankees in New York, the son had his name: Rogers Hornsby McKee. Reported as “being bashful about his name,”6 McKee dropped the “s” from his first name, becoming simply “Roger,” when he started school.7

Roger McKee’s athletic skill set matched his father’s baseball ambitions for him. By the age of 8 he was pitching for a Shelby youth team,8 and as a 15-year-old junior in in 1942 was unbeaten on the mound for Shelby High School.9 That same season he pitched the Shelby Post 82 American Legion team to the North Carolina state championship with a 3-2 win in the state final.10 In the spring and early summer of 1943, the whip-thin (6-feet-1, 160 pounds) 16-year-old lefty was 9-1 for the Shelby Legion team, with a no-hitter. He averaged 14 strikeouts per outing and hit .500, but the team reached only the state semifinals.11 McKee and another future major leaguer, Smoky Burgess, from nearby Forest City, were Shelby’s go-to battery. McKee pitched 29 innings in three games over five days in the 1943 Legion tournament, but lost the elimination game to Albemarle, 7-4.12

Philadelphia Phillies scout Cy Morgan13 first spotted McKee as a high-school and Legion sensation in 1942. “I’ve looked all over the world for this kid and I’m staying here till I get him,” Morgan enthused just before McKee signed for a reported $5,000 bonus14 on August 12, 1943, at the end of the Legion season.15

Morgan immediately hustled McKee to Philadelphia, where Freddie Fitzsimmons had taken over managerial duties from Bucky Harris on July 28.16 With Organized Baseball then in its second of four seasons of the personnel scrambles necessitated by World War II, Fitzsimmons, as most managers did, needed pitching; at age 16 and a week removed from Legion baseball, McKee was a major leaguer.

When play closed on August 17, 1943, the Phils were only 10 games under .500 at 51-61 but had dropped to seventh place in the National League, 22½ games behind the Cardinals. In the midst of a lengthy homestand, they trailed those Cardinals 5-0 after six innings in the first game of a doubleheader on August 18 when Fitzsimmons gave McKee his major-league baptism at the age of 16, sending him out to face Harry Walker, Stan Musial, and Walker Cooper in the top of the seventh inning with the Phillies trailing 5-0.17 Showing some understandable nerves, McKee allowed Walker a bunt single and then walked Musial. But he recovered to get Cooper on a 5-4-3 double play before retiring Whitey Kurowski on a fly ball to right field. He yielded a run in the St. Louis eighth on a walk, sacrifice, and double, but shut down the Cardinals in the ninth, this time besting Musial, who bounced a fielder’s choice groundball to second base after Walker’s leadoff single.

McKee pitched a third of an inning of ineffective relief against Cincinnati on August 22 as the Reds thrashed the Phillies 20-6. The next night Fitzsimmons started McKee in an exhibition game at Wilmington, Delaware, against the Phillies’ Class-B Blue Rocks farm club in the Interstate League. The lefty responded with a five-hit, complete-game win. Wilmington bunched two of its hits against McKee to cost him a shutout in the ninth inning as Philadelphia won, 5-1.18

After the successful exhibition outing however, the rookie rode the bench for more than a month19 before Fitzsimmons gave him another inning of work, on September 26 in St. Louis.

But then, as the Phillies closed out the season in Pittsburgh on October 3, McKee got what would be his only major-league start in the 1943 finale – the second game of a doubleheader at Forbes Field. The Phillies had won the opener, 3-1, behind Dick Barrett.20 McKee’s second-game mound opponent, Cookie Cuccurullo, another lefty, was himself making his major-league debut but was, at age 25, an elder statesman compared with the just-turned-17 North Carolinian.

This day, greater youth prevailed, as Cuccurullo gave up seven runs through seven innings and Bill Brandt, his replacement, yielded another four. Meanwhile, McKee was solid, scattering five hits and holding Pittsburgh to three runs. At the plate, with the game tied 3-3 in the top of the seventh inning, Cuccurullo’s last turn on the mound that day, McKee worked a leadoff walk and scored the go-ahead run on Benny Culp’s single; the Phillies tallied three more to take a 7-3 lead. Then, with two outs in the Philadelphia ninth and his team comfortably ahead, McKee drilled a single off Brandt to drive in the final Phillies run before closing out the Pirates without a baserunner in their half. It ended as an 11-3 Philadelphia romp.

McKee thus became and remains (as of 2020) the youngest major leaguer (at the age of 17 years, 17 days) in the modern era to pitch a complete-game win.21

Wartime travel restrictions continued to impact baseball as the Phillies, now sporting the additional nickname Blue Jays,22 traveled 33 miles from their home at Shibe Park to 1944 spring training in Wilmington, Delaware. Camp didn’t open until April 1, and extended only through April 15, with 10 exhibition games scheduled.23 It was cold, wet, and windy, and with limited time to prepare, the 17-year-old began to throw full-throttle early – probably too early. “It was cold. There was snow on the ground. We worked out in a big field house, then we finally got to go outside. I don’t know what it was, but the speed of my pitches wasn’t wasn’t there. My arm didn’t hurt and I could throw without pain, but the ball didn’t get to home plate as fast. That made a big difference,” McKee recalled many years later.24 The portside velocity that had so excited scout Cy Morgan just the summer before and had carried McKee to a complete-game win in his first major-league start just wasn’t there anymore. McKee was on the Phillies roster when the 1944 season opened,25 but his out-of-nowhere lack of velocity concerned the Philadelphia brass. The game was then decades away from today’s sophisticated handling of young pitchers to preserve their arms; after nine games over which the Phillies were 5-4 and McKee never threw a pitch in competition, all the club did was option him to Wilmington.26

McKee gave his all in 106 innings over 20 games for Wilmington in 1944 with his diminished arm, posting a 6-8 record and a 4.25 ERA. A trio of successive Wilmington managers, including Cy Morgan, used him in an additional 34 games at first base and center field; he batted .225 in 151 at-bats and hit three home runs, tied for third on the club. The Phillies recalled the lefty at the end of the season – he got two innings of mop-up relief in a 15-0 loss to the Chicago Cubs on September 26.

This was the final appearance of McKee’s five-game major-league career, which featured a quintet of “ones” – a historic game-winning pitching accomplishment in his one start for a 1-0 pitching record; one hit, one run scored, and one RBI as a hitter.

That year, 1944, had acquainted McKee well with the disappointments professional baseball career could bring, but there was happiness as well. He married the former Denice (pronounced “Dennis”) Spangler in Gaffney, South Carolina, on July 19.27 Denice and Roger had gone to separate high schools – she at smaller Piedmont High in Lawndale in northern Cleveland County; Roger at Shelby28 — but they both played high-school basketball and met at one of her games in 1942. After traveling with Roger throughout his minor-league career, Denice earned a bachelor’s degree in business education and a master’s degree in business economics at Appalachian State Teachers College (now University) in Boone, North Carolina, and taught business classes and did counseling in the Shelby city school system.29 She also worked in the office of her family’s Spangler Roofing and Siding business and still, in her 90s, kept books for various Spangler family businesses.

The couple had one child, Rogers Hornsby McKee Jr., born November 9, 1947. He is now retired after a career as an industrial engineer with PPG in Shelby.30

Two days after his 18th birthday in September 1944, Roger McKee registered for the Selective Service draft. He entered the US Navy as a draftee early in 1945, went through basic training with a group that included Stan Musial at Bainbridge (Maryland) Naval Training Center, and was part of a detachment from Bainbridge called to Washington to participate in funeral services for President Franklin D. Roosevelt in April 1945. McKee later played in an eight-team service league at Pearl Harbor,31 and was posted in Japan with US occupation forces after the war ended There, he saw the aftermath of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs. McKee was discharged on April 30, 1946.

This was early enough in the baseball season for him to join the Terre Haute Phillies of the Class-B Three-I League. With Terre Haute, McKee pitched eight innings in four games and picked up a win. But he was now essentially a first baseman and occasional outfielder,32 hitting a useful .318 in 280 at-bats. The Phillies, however, had signed McKee as a pitcher and when they elected to expose McKee to the Rule 5 draft in November 1946, the Cardinals selected him.33

McKee had told a Shelby-area writer, “Well, I’d rather play ball than anything else I know of. It just gets in your blood,”34 when he signed as a 16-year-old. Now, 3½ years later and no longer a Phillie, he embraced that philosophy and embarked on a 10-year minor-league journey with St. Louis and three other organizations that included 12 teams across classification levels from Triple A to D.35 Except for a single appearance in 1955 in Class B, he had stopped pitching, but he had some serviceable years as a hitter. He seemed to do it best for the Baton Rouge Red Sticks of the Class-C Evangeline League, where he won the league batting title at .357 in 1953. He had 13 home runs that season, but showed more power the next year – still with the Red Sticks, he clouted 33 homers, good for third-best in the power-happy 1954 Evangeline League, and hit .321 in another solid year at the plate.36

McKee played at higher levels in 1955 and 1956 before returning to Baton Rouge for 75 games at the end of the 1956 season and hitting .307. He finished his career at age 30 in 1957, getting into 54 games with Baton Rouge and sipping a cup of coffee with Topeka of the Class-A Western League in the Milwaukee Braves organization.

Roger McKee returned home to Shelby after baseball. He worked for a while for a polyester fiber manufacturer, then went to work as a city route mail carrier for the US Postal Service, retiring after 30 years of service. He assisted the baseball coaching staff at Shelby High School and in the early 1960s was head coach of the American Legion Post 82 team for which he had pitched so well himself. Jim Horn, a North Carolina Legion baseball co-chair, remembered, “I know he was one of the greatest to come through our area. I followed him [when I was] a little guy and always looked up to him.” When I was playing Legion ball, if we were going to be facing a left-hander, he’d come out and pitch batting practice to us. His whole life was that way – he was there to help you if he could.”37

McKee had taken courses as Southern Business College in Shelby during some of his offseasons. In 1966, at the age of 40 and a decade after he had played his final minor-league game, McKee took courses at Gardner-Webb University in nearby Boiling Springs, and although he didn’t graduate with a degree, ultimately received a distinguished alumni designation for his service to the school. He served on the board of directors of Gardner-Webb’s athletic booster group, the Bulldog Club, and established the Roger McKee Baseball Scholarship at Gardner-Webb. McKee was inducted into the Cleveland County (North Carolina) Sports Hall of Fame in 1977. He served on the Shelby Parks and Recreation Board.

Roger, a 10-handicapper, taught Denice to play golf – well enough that she has two holes in one; Roger never had one. Roger also “loved to travel,”38 and the couple did so widely, visiting all 50 states and parts of Canada and Mexico. Denice also told the author of Roger’s avid interest in reading, where his tastes tended to history, biographies, and other nonfiction. He paid little attention to baseball after his time in the game, and on the rare occasions when he would watch a televised game, tended to dismiss it with “the game these days is entirely too long.”39 Instead, he closely followed Duke University basketball and football.

By August 2009, when the Phillies invited Roger to their Alumni Weekend event, he had limited mobility and was reluctant to attend. Roger Jr. contacted the Phillies for his dad, and the club arranged an all-expenses-paid trip for the entire family. Despite being in a wheelchair, Roger had a “wonderful time” being recognized in the on-field ceremonies at Citizens Bank Park along with Phillies’ standouts such as Robin Roberts, Steve Carlton, and Mike Schmidt. “The Phillies couldn’t have been kinder or more considerate.”40

Roger and Denice McKee celebrated their 70th wedding anniversary on July 19, 2014.

Shortly thereafter, on September 1, 2014, Roger McKee died at Cleveland Regional Medical Center in Shelby after a brief series of strokes.41 He was 87 and was survived by Denice, son Roger Jr. and wife Barbara, sister Elissa McKee Bright, two grandsons, and a great-grandson. He and Denice had been longtime members of the Shelby First Baptist Church and his memorial service was held there on September 5, 2014.

Roger McKee is buried at the Double Shoals Baptist Church Cemetery in Shelby.42

Acknowledgments

I sincerely appreciate the time Denice McKee and Roger McKee Jr. spent with me at Roger’s home near Shelby on August 8, 2018, and the hospitality accorded my wife and me by Roger Jr.’s wife, Barbara. Their collective recollections of Roger McKee, both during his baseball career and over the 56 years back in Shelby after he hung up his spikes, certainly make this biography better than anything I could have produced without their kind assistance and interest.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used the Newspapers.com website for minor-league game stories, box scores, and general reference material, and the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for major-league box scores, player and team pages, and pitching and batting logs. I accessed US Census data and other information on the McKee and Spangler families through Ancestry.com at my hometown Transylvania (North Carolina) County Library. My SABR colleague Kevin Larkin reviewed Roger McKee’s file in the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and provided copies of pertinent material.

Notes

1 Rogers Hornsby collected 2,930 hits in his 23-year career. He won seven National League batting titles between 1920 and 1928. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1942. Roger McKee hit .357 with the Baton Rouge Red Sticks to win the 1953 Evangeline League batting title.

2 For an account of a game in which two player-managers, Ty Cobb of the Tigers and George Sisler of the Browns, got into the act, see the author’s “October 4, 1925: Heilmann Grabs AL Batting Title; Cobb ‘Saves’ the Day,” SABR Baseball Games Project, sabr.org, accessed July 9, 2018.

3 US Decennial Census figures report Shelby’s 1920 population as 3,609. By 1930, it was 10,789, an increase of 198.9 percent.

4 Author’s conversation with Denise McKee, Roger McKee Jr., and Barbara McKee, Shelby, North Carolina, August 8, 2018. (Hereafter: “August 8 conversation.”)

5 “Rather Play Than Eat – That’s Phils’ McKee,” Harrisburg Telegraph, October 21, 1943: 21.

6 John H. Whoric, “Sportorials” column, Daily Courier (Connellsville, Pennsylvania), November 1, 1943: 7.

7 “Rather Play Than Eat.” The hand-printed name and signature on McKee’s Selective Service registration card, dated September 18, 1944, are both “Roger Hornsby McKee.”

8 Whoric.

9 “Rather Play Than Eat.”

10 “Gardner-Webb Alum, Pro Baseball Player, Passes Away,” gardner-webb.edu/newscenter/gardner-webb-alum-pro-baseball-player-passes-away/. September 4, 2014, accessed June 29, 2018.

11 Whoric.

12 Shelby (North Carolina) Star clipping, August 1943 date missing, unattributed, from McKee family baseball scrapbook; August 8 conversation.

13 William Prestwood “Cy” Morgan never played in the major leagues. He was a steady .300-plus-hitting outfielder over 11 minor-league seasons from 1926 through 1939 for teams ranging in level from Class D to Class A. He scouted for three major-league organizations from 1941 through 1965. Cy Morgan (scout) entry, Baseball-Reference Bullpen, accessed September 6, 2018.

14 The $5,000 figure is from the newspaper item cited in Note 15. In a profile of McKee done in connection with the Phillies’ 2009 Alumni Weekend observance however, McKee himself recalled the figure to have been $3,000. Larry Shenk, Roger McKee profile in The Phillies – An Extraordinary Tradition, Scott Gummer, ed. (San Rafael, California: Insight Editions, 2009), 53. Whatever the amount, Denice McKee told the author that Roger McKee used a significant portion of it for a down payment on a house for his parents and siblings.

15 Catherine Bailey, “Shelby Youth in the Majors,” Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Telegram, August 20, 1943: 6. The signing date is from the status card in Roger McKee’s file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

16 The 41-year-old Fitzsimmons had begun the 1943 season as a pitcher with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was released on July 27, the day before he took over the Phillies.

17 With his debut, McKee became the youngest player in the 1943 National League. Rogers Hornsby was long gone from St. Louis by 1943. After his 1926 Cardinals won the World Series against the Yankees, he moved on to manage the New York Giants in 1927. By 1943 he was signed to continue managing the Fort Worth Cats of the Texas League, but the circuit suspended operations from 1943 to 1945 due to World War II. C. Paul Rogers, “Rogers Hornsby,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org, accessed July 5, 2018.

18 “Phils Trounce Wilmington, 5-1,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 24, 1943: 23.

19 McKee turned 17 on September 16, 1943.

20 Roger McKee Jr. recalls his father’s telling him that had the Phillies not won the opener, Fitzsimmons may well have used a different starter for the second game. August 8 conversation.

21 “Rogers [sic] McKee, ‘Teenage Tar Heel Twirler,’” DiamondsInTheDusk.com, accessed July 6, 2018. The baseball term “modern era” refers to all National League and American League seasons from and after 1901. The American League joined the older (1876) National League as a major league for the 1901 season.

22 The additional name came from a 1943-44 offseason contest aimed at boosting fan interest. Stan Baumgartner, “Bobo”s First Press Confab Balks Philly,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1944: 18. According to the 1944 Phillies’ team page at Baseball-Reference.com, “Blue Jays” was used by the team for the 1944 and 1945 seasons only, then dropped “due to fan outrage/apathy.”

23 The Sporting News, January 13, 1944: 14, and March 9, 1944: 6.

24 Shenk, McKee profile.

25 The Sporting News, April 6, 1944: 15.

26 “Five Players Dropped by Phils,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1944: 18.

27 “We loved each other, and we eloped,” Denise McKee told the author. Gaffney is just across the state line from Shelby and at the time was “the place” for eloping young couples to be married. Denice McKee recalled that Roger had pitched the night before he left for Shelby but the newlyweds were back in Wilmington in time for his next start. August 8 conversation.

28 Denice McKee explained that at the time, high school in North Carolina consisted of only three years. August 8 conversation.

29 “70th Anniversary: Mr. and Mrs. Roger McKee,” ShelbyStar.com, accessed June 28, 2018; August 8 conversation.

30 August 8 conversation.

31 Gary Bedingfield, “Those Who Served,’ BaseballInWartime.com, accessed July 6, 2018; August 8 conversation. Roger McKee Jr. notes that his father told him one of the few times he recalled being booed was when he got Ted Williams out in a service game. “They wanted to see Ted hit the ball out.”

32 Box scores from various Midwestern newspapers covering the 1946 Three-I League show McKee playing first base and batting either fourth or fifth for Terre Haute. At the end of the season, a story reporting his selection in the draft by the Cardinals described McKee as a “star … first baseman” for Terre Haute. Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, November 6, 1946: 23.

33 Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, November 6, 1946: 23.

34 Bailey.

35 McKee did not play anywhere during the 1951 season.

36 Denice and Roger Jr. accompanied McKee most of these summers. Denice remembers “enjoying meeting new people wherever we went.” Having been only nine years old when his father retired from baseball, Roger Jr. has few memories from those years other than “playing under the bleachers and looking for nickels, probably in Baton Rouge.” August 8 conversation.

37 Alan Ford, “Local Baseball Legend McKee Passes Away,” Shelby Star, September 4, 2014: online edition, ShelbyStar.com, accessed June 28, 2018.

38 August 8 conversation.

39 August 8 conversation.

40 August 8 conversation.

41 Author’s telephone conversation with Roger McKee Jr., July 9, 2018.

42 Roger McKee obituary, Shelby Star, undated, accessed through Legacy.com June 28, 2018.

Full Name

Roger Hornsby McKee

Born

September 16, 1926 at Shelby, NC (USA)

Died

September 1, 2014 at Shelby, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.