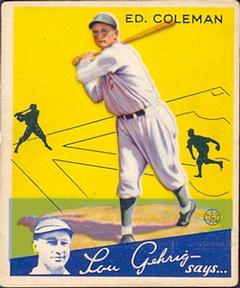

Ed Coleman

In April 1933, Ed Coleman, who had shaved a full five years from his true age, entered his first full major league season tabbed as one of the Philadelphia Athletics rising young stars. “[He] is regarded as a sure-shot to bat far over the .300 mark,” The Sporting News wrote. “[H]e gave every evidence of being a natural” during a brief trial in 1932.1 Sometime later, no less a judge than future Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby offered that “when it comes to long-distance hitting … [Coleman] compare[s] with the best in this league — fellows like [Lou] Gehrig, [Al] Simmons, [Babe] Ruth [and Jimmie] Foxx … They can all drive the ball terrific distances.”2

In April 1933, Ed Coleman, who had shaved a full five years from his true age, entered his first full major league season tabbed as one of the Philadelphia Athletics rising young stars. “[He] is regarded as a sure-shot to bat far over the .300 mark,” The Sporting News wrote. “[H]e gave every evidence of being a natural” during a brief trial in 1932.1 Sometime later, no less a judge than future Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby offered that “when it comes to long-distance hitting … [Coleman] compare[s] with the best in this league — fellows like [Lou] Gehrig, [Al] Simmons, [Babe] Ruth [and Jimmie] Foxx … They can all drive the ball terrific distances.”2

But injuries and an eventual falling out with Athletics owner-manager Connie Mack led to Coleman’s May 1935 trade to the St. Louis Browns where he was united with Hornsby, the club’s skipper. Elated to add the slugger to his offensively challenged team, the Rajah soon soured on Coleman when the lefthanded hitter reported to the Browns 1936 spring training overweight. Relegated largely to a pinch-hitter, he turned out to be a good one. Coleman established an American League single-season record 20 safeties before eventually being sent to the American Association the following spring. He spent the next five years bouncing around the minor leagues before retiring from Organized Baseball.

Parke Edward (“Ed”) Coleman was born on December 1, 1901, the first of two children of Phillip L. and Carrie (Bair) Coleman, in Canby, Oregon, 21 miles south of Portland. Phillip, an Ohio native who moved to Oregon in the late 1800s, was a high school teacher and principal who had fathered two sons in a previous marriage. The eldest of these, Ralph Orval Coleman, would have a profound impact on Ed. A superb athlete at Canby High School and Oregon Agricultural College (later Oregon State University), Ralph became a pitcher in the Class-AA Pacific Coast League in the 1920s, primarily for the Portland Beavers. He eventually returned to Oregon Agricultural where he launched a collegiate Hall of Fame career as the Beavers head baseball coach.3

Following in his step-brother’s footsteps, Ed Coleman achieved his own success as a pitcher at Canby High and Oregon Agricultural College. After signing with the Logan (Utah) Collegians in the Class-C Utah-Idaho League in 1926, Coleman’s career was jeopardized after just 14 appearances when the righthander developed arm problems. Moved to the outfield to take advantage of his explosive bat, Coleman hit .380 with a .581 slugging percentage, figures that would have placed among the league leaders had he secured more than the 129 at-bats he got. Inexplicably, the Collegians released him midway through the season.

Coleman bounced among three teams in the Utah-Idaho League over the next two years. In 1928, while splitting time in Idaho between the Twin Falls Bruins and the Boise Senators, he briefly returned to the mound but garnered little success. Instead, he progressed steadily as a hitter, clubbing a circuit record 26 home runs in route to a league best .385 average. Despite these eye-popping numbers, Coleman’s faulty defense hindered his staying with one team for any length of time. Later reports admitted that “Ed was no gazelle with the glove.”4

But his offensive prowess attracted the Class-AA Hollywood Stars in the fall of 1928 when the Pacific Coast League club, who lost slugger John Kerr to the Chicago White Sox in the rule 5 draft, purchased Coleman from the Senators. The arrangement proved short-lived when the Stars sold him to the rival San Francisco Seals before the start of the 1929 season. In the elongated PCL seasons Coleman shared outfield duties with eight other players in 1929 and 1930, averaging 123 appearances per season while hitting .322 with 14 homers.

As he would several years later, in 1931 Coleman appears to have requested a relocation to Portland, a request that was accommodated when the Seals sold him to the Beavers in February. Except for a 13-year span near the end of his life, Coleman always returned to the Portland region during the off-seasons and in retirement. He was especially interested in returning in 1931 following the birth of his first child. Five years earlier in Silver Bow County, Montana, Coleman had married Katherine Rose Budd. Three years his junior, the Minnesota native bore their first child, Glen Budd Coleman, during the 1929 season. A daughter, Katherine, followed six years later.

Though his defense improved little during the 1931 season — a near league leading 15 errors by an outfielder — Coleman’s offense more than compensated. Pacing the Beavers with 187 games, he led the league with 53 doubles (tied with teammate Billy Rhiel) and 467 total bases while establishing career high marks in at-bats (768), hits (275), triples (14) and home runs (37) — an offensive surge he credited to Beavers skipper Spencer Abbott. The only downside to Coleman’s season was his struggles against lefthanded pitching, a problem that would plague him throughout his career. By this time Coleman had already shaved five years from his true age and sportswriters, who were comparing him to fellow PCL youngsters Frankie Crosetti and Dolph Camilli, anointed him as “the most improved player in the league.”5 During the offseason, several major league clubs approached the Beavers about acquiring Coleman, and in October reports surfaced that the slugger had been sold to the Boston Braves. Instead, on November 12, Connie Mack sent a hefty package of six Philadelphia Athletics including outfielder Jimmy Moore and catcher Joe Palmisano to Portland for Coleman and pitcher Joe Bowman.

Coleman’s chances of immediate success in the big leagues were more likely with the perennial second division Braves than with the reigning AL champions. Despite a strong 1932 spring training that included a two-homer, five-RBI game against the Brooklyn Dodgers on March 17 — a performance contributing to an assessment of him as “a genuine clean-up clouter who, when his six foot two and two hundred pounds of weight connect, blasts the ball out of sight” — Coleman was projected as merely a reserve behind a solid outfield anchored by future Hall of Famer Al Simmons.6

On April 15, 1932, in the Athletics second game of the season, Coleman made his major league debut at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park pinch-hitting for pitcher Lefty Grove. In the seventh inning, Coleman drove a single to center field against righthander Red Ruffing, advanced to second on an error, and scored on a double by outfielder Mule Haas in an eventual 9-8 comeback win over the New York Yankees. Eight days later, following three more substitute appearances, Coleman made his outfield debut after pinch-hitting for outfielder Bing Miller in a blowout loss to the Yankees.

On May 30, in only his third and fourth starts of the season during a doubleheader sweep against the Washington Senators, Coleman went 6-for-9 and scored four runs while collecting his first major league home run, a three-run shot against veteran righty Firpo Marberry. Seemingly convinced that he had a budding star in his midst, Mack continued putting Coleman in the lineup where he continued hitting at a .364 pace. This impressive performance came to an abrupt halt on June 10 when Coleman, trying to score from third on an infield grounder, broke his ankle on the slide. Lost for the season, he had put up an impressive display of numbers in his 73 at-bats: .342/.351/.507.

During the offseason, the often cash-strapped Mack, believing that Coleman could step into a starting role in 1933, sold Haas, Simmons, and infielder Jimmy Dykes to the White Sox for $100,000. With the emergence of rookie Bob Johnson, combined with 27-year-old Doc Cramer and Coleman, whom they thought was just 26, the Athletics proudly pointed to this trio of “baby outfield[ers]” that would patrol their garden for many years.7 But this rosy scenario did not envision Coleman’s being limited to pinch-hitting duties throughout the first three weeks of the 1933 season after a spring training injury. When he was inserted into the lineup, Mack slotted him in the clean-up spot ahead of future Hall of Famer Jimmie Foxx until the power production anticipated from Coleman proved illusory — a mere four homers throughout the season’s first half. Despite maintaining a batting average generally topping .290 and a string of hits that included a first inning single on June 4 foiling Yankee righthander Johnny Allen’s bid for a no-hitter, Coleman’s lack of power proved a major disappointment to Mack. Though his ninth inning pinch-hit homer on July 24 helped to tie franchise record three dingers in one inning, the blast proved to be his last of the season. As Mack turned increasingly toward rookie Lou Finney to fill the club’s right field needs, Coleman garnered just 11 plate appearances throughout the last six weeks of the season and finished with a .281/.318/.410 line in 388 at-bats.

With his ankle fully restored, Coleman reported to the Athletics 1934 spring training in superb shape to successfully reclaim the club’s right field post. On April 30, following a slow start to the season, Coleman compiled a season-best seven-game hitting streak that helped launch a 29-for-90 run through June 5. Largely relegated to pinch-hitting duties following a violent on-field collision with second baseman Dib Williams on July 2, Coleman, in a harbinger of his future success, collected hits in five successive pinch-hit appearances from July 17 through July 22. But conspicuously along with these bright spots came the same lack of power that had plagued Coleman the preceding season. Except for one blaze of glory — a three-homer game against the White Sox on August 17 — Coleman garnered just one additional dinger in 88 at-bats through August 22. Following an 0-for-23 at the end of the month, a drought that brought the wrath of the Philadelphia fans upon his head, Coleman was used in just two pinch-hit appearances over the club’s last 33 games of the season. The handwriting was on the wall. During September, the Athletics dangled him as trade bait to the Yankees and several other teams but found no interest.

Reports later surfaced that Coleman had “had differences with Connie Mack,” a scenario that, if true, seemingly ensured his departure from Philadelphia.8 Despite a strong 1935 spring training, one in which he overcame a severe knee injury in grapefruit league play to produce at a high level, Coleman lost his job to rookie right fielder Wally Moses. Banished to the farthest end of the bench, he made just one start and nine pinch-hit appearances through the first five weeks of the season before Browns manager Rogers Hornsby arranged a trade that sent veteran hurler George Blaeholder to the A’s for Coleman and righthander Sugar Cain. Long a frequent advocate of Coleman’s, Hornsby immediately plugged him into the starting lineup where he collected four hits in his first six at-bats. On May 25, in just his fourth game with the team, Coleman clubbed two homers, including a ninth inning go-ahead grand slam, in an eventual 8-7 loss to the Yankees. “[T]he Browns … are at least 50 per cent stronger on the offensive than they were before I obtained … Coleman,” Hornsby chirped. “[He] looks like a sure .300 batter to me.”9 Though Coleman fell 13 points short of that lofty threshold, he succeeded in placing among the team leaders in homers (17) and slugging percentage (.499) while pacing the club with nine triples. Moreover, Coleman, who was often criticized for his defense, led the AL in assists by a right fielder while also placing among the circuit leaders in fielding percentage and putouts.

In 1936, Coleman’s favored status with Hornsby was quickly tarnished when the outfielder reported to the Browns spring training 19 pounds overweight. Though he began the season as the club’s right fielder — a sizzling start that included four hits and six RBIs in his first 13 at-bats — sophomore outfielder Beau Bell soon replaced him. The Browns began shopping Coleman, turning down an offer from the Class-AA Montreal Royals in May. Several back-and-forth negotiations with the Dodgers throughout the year also proved fruitless. Described as a player “inclined to brood … [with a tendency] to lose confidence,” Coleman stepped into his new role as the Browns pinch-hitter deluxe with great vigor by collecting an AL record 20 pinch-hits in 1936 (a mark that stood for 30 years).10 One such hit came on September 26 in the second game of a doubleheader in Chicago when Coleman lined a bases-loaded three-run double against White Sox righthander Monty Stratton. The appearance proved to be Coleman’s last. He ended his major league career with a .285/.345/.459 line in 1,337 at-bats.

In spring 1937, the Browns, who had possessed a major-league worst 6.24 ERA the previous season, tried reconverting Coleman into a pitcher. After this experiment proved unsuccessful, the club traded him on March 30 to the American Association’s Toledo Mud Hens, the Detroit Tigers Class-AA affiliate; the move completed a September 1936 transaction that sent first baseman Harry Davis to St. Louis. Believing that he had successfully extracted a promise from the Browns that, if sent down, he would be traded to a Pacific Coast League team to be close to his family, Coleman expressed disappointment before grudgingly acknowledging his fate. “It’s all in the game,” he said. “I hate to go down after five years in the big league, but maybe I’ll slug my way back again.”11 Though a foot injury contributed to a slow start to the season, Coleman’s second half surge allowed him to finish among the American Association leaders with 25 home runs while also setting a Mud Hens record 123 RBIs in a 154-game schedule. He was on pace to duplicate these numbers in 1938 before being limited — presumably by injuries — to just 119 games. Despite limited play, Coleman still finished among the league leaders in batting (.332) and slugging (.533). Throughout this two-year surge there was no evidence of interest from the big leagues. In December 1938, Coleman got his wish to play closer to home when the Mud Hens sold him to the Portland Beavers.

Coleman’s joy of playing before family and friends proved short-lived when, midway through the 1939 season, while hitting at a .344 pace with 16 homers, he suffered what many observers thought would be a career-ending knee injury. He fought his way back to health in 1940 only to encounter the Beavers pursuing a youth movement. Despite his .317 average with nine home runs in just 268 at-bats, Coleman was released in June. The Oklahoma City Indians in the Texas League promptly signed him where Coleman was reunited with manager Rogers Hornsby. But he made just 22 appearances before he was released in August. That same year he was granted free agency and awarded $3,000 from Commissioner Kenesaw Landis, one of 91 players deemed disadvantaged when the Tigers stashed them in the minors in 1938. But it was already too late for Coleman. In 1941, he played in just six games with the Class-B Salem (Oregon) Senators in the Western International League before retiring to Portland.

During the Second World War, while working for a war-industry ironworks company in Portland, Coleman returned to his beloved game to play right field for the Commercial Iron Wolves. And he surfaced again in 1950 at a Far West League Old-Timers Game in Eugene, Oregon. But these were just two of few sightings of the private, soft-spoken man. Coleman was rarely quoted both throughout his playing career or afterward, something observers attributed up to his slight speech impediment.

Coleman was widowed in 1945 following the early passing of his wife. Four years later he married California native Esther Williams. They settled near Sacramento before returning to Canby around 1960. In the spring of 1964, Coleman contracted a severe illness, and on August 5, four months shy of his 63rd birthday, he succumbed to the undisclosed illness in an Oregon City, Oregon, hospital. He was buried at Zion Memorial Park in Canby.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com. The author wishes to thank SABR members Bill Mortell for his valuable assistance, and Tom Schott for review and edit.

This biography was fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 “New Tail to A’s Kite,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1933: 1.

2 “Scribbled by Scribes,” ibid., May 17, 1934: 4.

3 Ralph’s younger brother Glen, who appears to have played professional baseball in the Class-C Utah-Idaho League in 1927, became the athletic director for Albany College in Albany, OR.

4 “Necrology: Ed Coleman,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1964: 38.

5 Matt Gallagher, “Spectacular Finish by ‘Frisco Climaxed Split Race on Coast,” The Sporting News,, October 29, 1931: 6.

6 Bill Dooly, “Connie Mack, Despite Defeat in World’s Series, Will Pin ’32 Hopes on Same Lineup, Using Recruits for Reserves,” The Sporting News,, February 25, 1932: 5.

7 Arnie Harala, “Mack to Gamble on New Tactics for His Fiftieth Season in Game,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1933: 1.

8 “Browns Trade Blaeholder to A’s for Cain, Coleman; Sell Newsom,” The Sporting News,, May 23, 1935: 1.

9 Dick Farrington, “Frisch Counts Four, Then Five, Pitchers,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1935.

10 Dick Farrington, “Hornsby Uses Psychology on Outfielder Coleman,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1936: 1.

11 “Training Camp Notes,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1937: 6.

Full Name

Parke Edward Coleman

Born

December 1, 1901 at Canby, OR (USA)

Died

August 5, 1964 at Oregon City, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.