Elbie Fletcher

Elburt Fletcher was an 18-year-old minor leaguer when he shared a spring training dugout with Babe Ruth. “He still had that marvelous swing, and what a follow-through, just beautiful, like a great golfer. But he was forty years old. He couldn’t run, he could hardly bend down for a ball, and of course he couldn’t hit the way he used to.” Ruth, joining the Boston Braves in 1935, was only weeks away from the end of his storied career. “One of the saddest things of all is when an athlete begins to lose it … and to see it happening to Babe Ruth, to see Babe Ruth struggling on a ball field, well, then you realize we’re all mortal and nothing lasts forever.”1

Elburt Fletcher was an 18-year-old minor leaguer when he shared a spring training dugout with Babe Ruth. “He still had that marvelous swing, and what a follow-through, just beautiful, like a great golfer. But he was forty years old. He couldn’t run, he could hardly bend down for a ball, and of course he couldn’t hit the way he used to.” Ruth, joining the Boston Braves in 1935, was only weeks away from the end of his storied career. “One of the saddest things of all is when an athlete begins to lose it … and to see it happening to Babe Ruth, to see Babe Ruth struggling on a ball field, well, then you realize we’re all mortal and nothing lasts forever.”1

In a big-league career that lasted 12 seasons, interrupted by World War II, Fletcher was a teammate of Ruth, who began playing in 1914, and Warren Spahn, who pitched until 1965. Never a star, Fletcher was a valuable player on mediocre teams, a graceful, wide-ranging first baseman who led the league in assists six times and excelled at digging throws out of the dirt. “Down deep, I felt that there was nobody that could hit a ball by me or throw a ball by me,” he said.2 At bat he was a line-drive hitter who walked more than he struck out and was chosen for one All-Star Game.

Elburt Preston Fletcher was born in Milton, Massachusetts, on March 18, 1916, the second child of the former Elizabeth MacLary and Elmer Preston Fletcher, a traveling salesman for an elevator manufacturer. The boy worked weekends in a vegetable market for 25 cents a day and used his quarters to buy seats behind first base at Fenway Park or Braves Field. It didn’t matter which team he saw; as a left-hander, he wanted to watch the first basemen, especially the silky George Sisler of the Braves. “I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be a big league first baseman,” he said.3

He was a high school phenom, chosen twice for the Boston Herald’s All-Scholastic team. In his senior year the Record-American newspaper invited readers to nominate deserving young players for an irresistible prize: a trip to spring training with the Braves. Elburt organized a write-in campaign by his friends and extended family to win the contest along with two other teenagers.

His Milton High teammates turned out to give him a noisy sendoff as he boarded a train for St. Petersburg, Florida, in March 1934. At the Braves’ hotel, he learned that he could order anything on the restaurant menu and just sign the check. But steak for breakfast several days in a row didn’t agree with him. Manager Bill McKechnie, hearing that the youngster was in distress, handed him “this big bag filled with liquid with some sort of nozzle on it.” Elburt got the first enema of his life. Every morning after that, coach Hank Gowdy met him for breakfast to order All-Bran and prunes.4

Before working out with the team each day, the young visitors had to go to school with a private tutor. Their classmates included daughters of McKechnie and Ruth, who was training with the Yankees in St. Pete. Elburt impressed the Braves with his slick glove work. “There’s one boy who has a real good chance of going somewhere,” McKechnie remarked.5

But first the boy went home to finish his senior year and complete his duties as class president. Twenty-four hours after commencement exercises on June 7, he began his professional career in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Braves signed him for $250 a month, a small fortune during the Depression.

After he hit .291 in Class A, the 18-year-old was an unlikely September call-up because McKechnie took a personal interest in him. He pinch-ran seven times for the Braves and went 2-for-4 in his only start. By the end of the game, he was playing behind reliever Bob Smith, who was more than twice his age.

McKechnie kept him for another spring training with the big club, where he encountered Ruth before the Braves sent him back to the New York-Penn League in 1935. He was hitting .365 for Wilkes-Barre in August when McKechnie brought him up. The Braves were suffering through a historically awful season—they lost 115 games—so even a green 19-year-old couldn’t hurt the team much. Thrust into the everyday lineup, Fletcher was overmatched; he batted just .236 in 39 games, but did hit his first home run at Wrigley Field on September 9 off the Cubs’ Tex Carleton.

He spent 1936 in Buffalo at the highest minor-league level, overpowering the International League with a .344 average, 44 doubles, and 17 home runs. Grown to 6 feet and around 180 pounds, he looked ready. McKechnie declared him the team’s regular first baseman for 1937.

After the debacle of 1935, the Boston club had changed ownership and changed its name to Bees, but the manager stayed to overhaul the roster. The rookie first baseman was batting a respectable .275 on July 4 before he collapsed in the second half to finish at .247 with a weak .629 OPS. McKechnie was more interested in Fletcher’s flashy glove work, because the Bees were built around pitching and defense. They allowed the fewest runs in the league and rose to fifth place at 79-73.

Fletcher called McKechnie “the finest manager anyone could have played for.”6 But the club’s success in 1937 won McKechnie a better job with the Cincinnati Reds for a reported $25,000 that made him one of the highest-paid managers. Casey Stengel replaced him in Boston.

Fletcher showed improvement in his second year, bumping his OPS up to .729. He felt secure enough to marry Martha Hanson after the season. Nicknamed “Busy,” Martha had been his girlfriend since they were 14.7

A month after their November 5 wedding, the groom found his job under threat. The Bees acquired first baseman Buddy Hassett, a Stengel favorite from their days together in Brooklyn and a left-handed hitter with a .304 career batting average. Fletcher went on the trading block, but when the 1939 season opened he was still at first base with Hassett stationed uncomfortably in right field.

By June 15 Fletcher was hitting .245, Hassett .338. Less than two hours before the midnight trading deadline, Fletcher was swapped to the Pirates for minor league infielder Bill Schuster and cash. Pirates president Bill Benswanger showed him a check for $20,000 made out to the Bees, who always needed money. Since the Bees were in Pittsburgh, he just changed clubhouses.

Fletcher was shocked to be sent away from his hometown team, but he later believed it was the best thing that could have happened to him.8 The deal changed his career dramatically.

It didn’t look so great at first sight. With Gus Suhr hitting .296, the Pirates appeared to have no need for another left-handed first baseman. “We bought Fletcher for protection,” manager Pie Traynor said.9 But the team was slumping, and Traynor shuffled his lineup within a week. Fletcher took over as the regular first baseman.

As soon as he joined Pittsburgh, he turned into a different—and much more dangerous—hitter. He had recorded a weak .666 OPS with the Bees. He raised that to .839 over the next 4½ years as a Pirate. Sportswriters were quick to explain that he benefited by getting away from the distractions of playing in his home town, and Fletcher seemed to agree: “You know, when I was playing for Boston I think I was trying too hard to make good. You know, playing before the home folks.”10

His transformation was more likely the result of moving from Braves Field, a terrible hitter’s park, to Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, which was fair to batters and pitchers. Fletcher had always hit better on the road for the Bees. As a Pirate, he became a consistent .280 hitter at home and away, and added power, with double-digit home runs for three straight years. Most important, he developed a keen batting eye, leading the league with on-base percentages above .400 for three years in a row.

Usually batting in the middle of the order, Fletcher delivered his only triple-digit RBI season with 104 in 1940. He was headed for his biggest year in August when he slammed a long drive to right field. Watching the ball as he rounded first base, he crashed into Cincinnati’s 6-foot-4 Frank McCormick and wrenched his knee. His power disappeared after that.

With the knee still hurting, he underwent surgery on October 21 to remove loose cartilage. The next day Martha gave birth prematurely to their first child, named Robert after teammate Bob Elliott.

Fletcher’s glove put him in the record book on June 6, 1941, when he tied a National League mark with 21 putouts in a nine-inning game. The Pirates pitcher, sinkerballer Rip Sewell, set a league record with 11 assists.

The Pirates, like the Bees, were going nowhere. They never rose higher than fourth place from 1939 through 1943. Fletcher expressed no great respect for manager Frankie Frisch, who took over in 1940 and was the opposite of the fatherly McKechnie: “He was aggressive and fiery and, God, teed off all the time.”11

At home in Massachusetts, Fletcher refereed basketball games and worked as a salesman at Gilchrist’s department store in the offseasons. When the military draft began taking married fathers in 1943, he was inducted into the navy on November 30. His main job was playing ball at the Naval Training Center in Bainbridge, Maryland. The base fielded a powerful team including big leaguers Dick Bartell, Bob Scheffing, Dick Sisler, and Bud Blattner. Fletcher joined a navy all-star team that went to Hawaii in the final months of the war and played in front of troops on 16 Pacific islands before and after the Japanese surrender.

Fletcher was discharged just in time for spring training in 1946. He came home to meet his new son, Elburt Jr., born while he was in the service. Although he was preparing for his 10th major-league season, Fletcher was only 30. Overjoyed to be back in his natural habitat, he frolicked like a kid in spring training in San Bernardino, California, pelting teammates with oranges. Spotting an old man shuffling past the team bus, he told Frisch, “Hey Frank, here’s a guy used to play shortstop with you and wants to have a chat.”12

When the season opened, the Pirates became the test case for the first effort to create a true players’ union. Organizer Robert Murphy, founder of the American Baseball Guild, targeted the club because Pittsburgh was a strong union town and the Pirates roster included a number of mediocre veterans nearing the end of their careers.

After team president Benswanger met with Murphy on June 5 and refused to recognize the Guild as the players’ bargaining representative, Murphy called a clubhouse meeting to urge the Pirates to strike that night. Fletcher and several others boycotted the meeting and took the field to warm up. The strike vote was postponed for two days.13

The union drive deeply divided the team. Although Fletcher was not identified as a leader of the anti-union faction, his friend Bob Elliott was, along with pitcher Rip Sewell and infielder Jimmy Brown. The players voted 20-16 in favor of a strike, but they had agreed in advance that they would not walk out unless two-thirds approved. The vote fell four short of two-thirds, and the Guild soon disappeared.14

Like many returning servicemen, Fletcher had trouble readjusting to big-league pitching. His average fell to .256 with just four home runs as he suffered with a persistent case of athlete’s foot, but his batting eye remained intact: He drew 111 bases on balls.

He faced another threat to his job when the Pirates bought Hank Greenberg from Detroit in January 1947. The former American League MVP had once hit 58 home runs in a season, and he had been primarily a first baseman. Joining second-year man Ralph Kiner in the lineup, he gave Pittsburgh the reigning home run champions from both leagues hitting back to back. The club moved the left-field wall in by 25 feet, creating a bullpen called Greenberg Gardens.

New manager Billy Herman planned to put Greenberg in left field, maintaining that would be easier on his 36-year-old legs. Fletcher’s sigh of relief didn’t last long. In the final spring exhibition game, he severely twisted an ankle running the bases and was on crutches on Opening Day. By the time he was able to return to the lineup in June, Greenberg owned first base.

Fletcher pinch-hit and filled in for Greenberg. He started only 36 games, batting .242/.364/.331. When Greenberg retired at season’s end, the Pirates quickly acquired two new first basemen, Ed Stevens and Johnny Hopp. Fletcher’s days were numbered in single digits.

Pittsburgh sold him to Cleveland for a bit more than the $10,000 waiver price. He was insurance in case the Indians’ first baseman, Eddie Robinson, didn’t recover from a leg injury. Lurking in the front office was none other than Hank Greenberg, who had signed on as Cleveland’s farm director. While he kept insisting he wouldn’t play, Greenberg suited up and worked out during spring training, doing Robinson and Fletcher’s morale no good, but he was never added to the active roster.

Competition for the job was settled when Fletcher hurt his foot running out a triple in a preseason game. Team trainers called it a sprain, but the injury didn’t respond to treatment. Fletcher never got into a game before he was released on May 9. He had been cut loose by the club that would win the 1948 World Series. It was the closest he ever came to a championship.

When he went home to Massachusetts, a doctor diagnosed a fracture of his metatarsal arch. An arch support allowed him to run while still in pain. Fletcher put out feelers for a big-league job, but his only offer came from Giants farm director Carl Hubbell: a contract with Triple-A Minneapolis. Hubbell was not a man to hold a grudge; Fletcher had broken up his no-hitter with a home run in Hubbell’s 250th career victory in 1943.

Reporting to the Millers, Fletcher said, “I’m in the position of having to play my way into shape.”15 After a slow start, he found his groove and hit .305 with 19 homers and 96 walks in 110 games. No major-league club showed interest, but he wasn’t ready to quit. The Giants agreed to send him closer to home, in Jersey City, in 1949. His wife and sons had just joined him and “put the food in the refrigerator” when the phone rang. He was going back to the big leagues and back to Boston.16

“I hadn’t stopped trying—but I had given up hope,” he said.17 The Braves bought Fletcher after their first baseman, Earl Torgeson, went down with a separated shoulder. Stepping into the lineup on May 22, he delivered two hits in his first game and kept his batting average above .300 for six weeks. Torgeson, while rehabbing his shoulder, got into a fight and broke his thumb. He was out for the year. That’s how 1949 went for the defending National League champions. As they sank to fourth place, manager Billy Southworth didn’t last the season.

The highlight of Fletcher’s season came on August 31, when fans honored the 33-year-old hometown boy with a night at the ballpark. He collected a truckload of gifts including a new Chevrolet and free baby-sitting services for a year. He celebrated with a two-run homer.

He tailed off in the second half, but still finished with a .798 OPS. That didn’t matter. Torgeson, who was only 25, was expected back in 1950, barring any further misadventures. The Braves released Fletcher in December.

“You know it’s coming, but you never think it’s going to quite get here,” he mused decades later. “I remember when I was a kid, maybe five or six years old, I had this favorite toy. When I misbehaved, my father would take it away from me for a few days. I always felt miserable when that happened, like my whole world had emptied out. That’s how I felt at the end, when they told me I was being let go, just the same as I’d felt when that toy was taken away.”18

Still not ready to give up, he crossed the continent when the Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels offered him more money than he had been making in Boston. On a club loaded with former big leaguers, he was hitting above .330 for most of the season. A case of mumps and a leg injury dragged the final figure down to .289.

Sixteen years after his professional debut, Fletcher announced his retirement at 34. “I had kinda lost my desire,” he said. “My legs were beginning to hurt.”19 He had a job waiting as a sportscaster with WBZ radio in Boston.

For the next decade Fletcher held several sales jobs and served on the city Parks Commission in Milton. Then he became director of recreation for the nearby town of Melrose, managing its playground, rec center, and golf course for 25 years before retiring. He died on March 9, 1994, just short of his 78th birthday.

Fletcher played 1,415 games without reaching the World Series, most of the time on losing teams. “You still play hard,” he said. “You want that base hit, that run batted in, you want to dig out that low throw, make that good play. You’re a professional, a big leaguer, and you take pride in that.”20

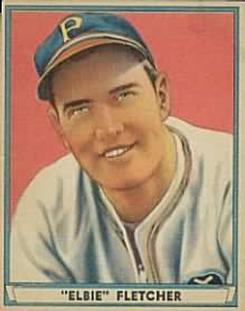

Photo credit

Play Ball baseball cards.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Rob Wood.

Notes

1 Donald Honig, Baseball When the Grass Was Real in A Donald Honig Reader (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 60.

2 Elbie Fletcher interview by Brent Kelley, March 17, 1992. SABR Oral History collection, https://oralhistory.sabr.org/interviews/fletcher-elbie-1992/.

3 Honig, Baseball When the Grass Was Real, 52.

4 Ibid., 54.

5 Associated Press, “Training Briefs,” North Adams (Massachusetts) Transcript, March 13, 1934: 10.

6 Fletcher interview.

7 William P. Hall, “Elbie Fletcher, Major Leaguer of Otis Street,” Milton (Massachusetts) Historical Society Newsletter, Fall 2006. http://www.miltonhistoricalsociety.org/Sampler/ElbieFletcher.html, accessed April 1, 2018.

8 Fletcher interview.

9 Lester Biederman, “Bees Get Schuster, Cash In Exchange For First Baseman,” Pittsburgh Press, June 16, 1939: 35.

10 Hy Hurwitz, “Elbie Fletcher Makes Good in Pittsburgh,” unidentified clipping in Fletcher’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

11 Honig, Baseball When the Grass Was Real, 57.

12 “Preacher Roe Joins Pirate Mates Today,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 20, 1946: 16.

13 Chester L. Smith, “Pirates Threaten Baseball Strike If Club Doesn’t Recognize Guild,” Pittsburgh Press, June 6, 1946: 6.

14 Vince Johnson, “Pirates Vote to Call Off Strike,” Post-Gazette, June 8, 1946: 1; Smith, “Pirates Reject Strike Planned By Guild, Take Field, Defeat Giants,” Post-Gazette, June 8, 1946: 1. Rosters were expanded to make room for returning servicemen, explaining the 36 votes.

15 “‘Must Play My Way Into Shape’—Fletcher,” Minneapolis Star, May 31, 1948: 32.

16 Fletcher interview.

17 Roger Birtwell, “Fletcher Gives Lesson in ‘How to Come Back,’” The Sporting News, September 7, 1949: 7.

18 Honig, The Fifth Season: Tales of My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), 202-203.

19 Fletcher interview.

20 Honig, When the Grass Was Real, 56.

Full Name

Elburt Preston Fletcher

Born

March 18, 1916 at Milton, MA (USA)

Died

March 9, 1994 at Milton, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.