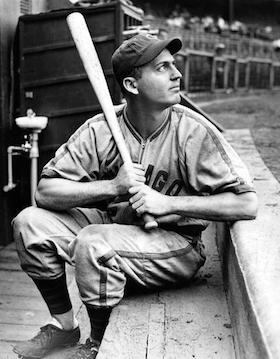

Billy Herman

The March 20, 1941, edition of the Sporting News brandished this headline on page 5: “Loyal Watchers Daffy About Dodgers’ Flag Chances; Scribes Already Arguing About World Series Plans.” Brooklyn’s “Bums” had finished a distant second to Cincinnati in 1940, but the beat writers were predicting an all-New York World Series come October. The hubbub surrounding the Dodgers’ chances was a pitching staff led by Kirby Higbe and Whitlow Wyatt. Big things were expected of Pete Reiser, who was taking over in center field for Dixie Walker, who was shifting to right. It was believed that Joe Medwick would bounce back from a subpar 1940 season. If there was one position the Dodgers might need to shore up for a successful pennant run, it was second base.

The March 20, 1941, edition of the Sporting News brandished this headline on page 5: “Loyal Watchers Daffy About Dodgers’ Flag Chances; Scribes Already Arguing About World Series Plans.” Brooklyn’s “Bums” had finished a distant second to Cincinnati in 1940, but the beat writers were predicting an all-New York World Series come October. The hubbub surrounding the Dodgers’ chances was a pitching staff led by Kirby Higbe and Whitlow Wyatt. Big things were expected of Pete Reiser, who was taking over in center field for Dixie Walker, who was shifting to right. It was believed that Joe Medwick would bounce back from a subpar 1940 season. If there was one position the Dodgers might need to shore up for a successful pennant run, it was second base.

It was not too long into spring training in 1941 before speculation arose that the Chicago Cubs might try to move their star second baseman, Billy Herman. Chicago general manager Jim Gallagher was very high on Lou Stringer, a second baseman who the front office felt was ready for the big leagues. Just as Herman had replaced Rogers Hornsby a decade earlier, Stringer was being relied on to succeed Herman.

Although Herman was the premier second baseman in the senior circuit, the club thought he had lost a step or two. Perhaps the time had come to unload him. Herman did not show it outwardly, but he was disappointed that he had been passed over twice to manage the Cubs. In 1938 Gabby Hartnett had been selected as a player-manager instead of Herman. Now Jimmy Wilson had been chosen to replace Hartnett.

The Dodgers emerged as the lead suitor for Herman, when general manager Larry MacPhail talked trade with Gallagher in spring training. Dodgers manager Leo Durocher favored Herman over his present second baseman, Pete Coscarart. In Robert Creamer’s book Baseball in 1941, he describes Coscarart as a “journeyman and nothing more.”1 Durocher considered the veteran Herman a “smart baseball player” he could pair with his young shortstop, Harold “Pee Wee” Reese.

Herman got off to a slow start in 1941, batting .194 after 11 games. In the wee hours of May 6, a deal was brokered. The Dodgers sent reserve players Johnny Hudson, Charlie Gilbert and $65,000 to Chicago for Herman. “Herman will help us more than you expect,” said the Lip. “He’ll steady the kid at shortstop. He’ll take charge of the infield. And he gives us sustained power on attack. Anywhere along the line right down to the pitcher we’re likely to blast.”2 Herman got right to work, going 4 for 4 in his debut on May 6 at home against Pittsburgh. “This is a great baseball town,” said Herman.”It’s like playing in a World Series game every day.”3 Four days later, Herman tied a career high when he went 5 for 5 against the Phillies, leading the Dodgers to a 4-1 victory at Shibe Park. “

Back in the Windy City, the Cubs’ Phil Cavarretta may have summed up the feelings of the majority of Cub fans. “When we traded Billy, I was sick, believe me. He went over to Brooklyn and won pennants.”4Herman took the high road. “I’ve got no squawk against the Chicago club,” he said. “They treated me great there, and you couldn’t ask to work for a better, more considerate organization.”5 Herman was inserted in the two hole of the Dodger lineup and batted .291. Brooklyn nipped the Cardinals by 2 ½ games to win the National League Pennant.

William Jennings Herman was born on July 7, 1909, in New Albany, Indiana. New Albany is located on the Ohio River in the southern part of the state; across the river sits Louisville, Kentucky. He was one of 10 children born to William and Elizabeth Herman. He was named after United States Secretary of State (1913-15) William Jennings Bryan, a three-time Democratic Party candidate for President (1896, 1900 & 1908), losing each time. Herman commented that he was named after a loser, and Herman hoped that it would not carry over into his baseball career. Although “Bryan” is often included as part of his name, Herman wrote in a players survey given by Cliff Kachline of the Hall of Fame, “My name is William Jennings Herman.”

Although the Hermans resided on a small farm in New Albany, the elder William made his living as a machinist at a factory in Louisville. Herman attended New Albany High School, but playing in the major leagues was the farthest thing from his mind. “I was a sub on the team-a substitute third baseman and shortstop. I never played regular in high school,” recalled Herman. 6 At the conclusion of his junior year, Herman dropped out of high school to work in a Louisville veneer manufacturing plant. He married his childhood sweetheart, the former Hazel Jean Steproe, in 1927. They had one son, Billy Jr., and divorced in 1960.

Herman was playing baseball for the New Covenant Presbyterian Church team in Louisville when he was noticed by Cap Neal, general manager of the Louisville Colonels, a Class AA club in the American Association. “(I) signed for nothing. Would have paid to get a contract with the Louisville Cardinals back in 1928 when they signed me. I still wasn’t any good,” said Herman. The Colonels sent him down to Class B Decatur, but he was returned to Louisville within a few days without even seeing the diamond. “When I returned, the Colonels were out of town. I hung around a week until Cap Neal got back to town and he sent me to Vicksburg-a class D town, as low as you can be sent. That’s as low as you can get – Class D- and I couldn’t make it. Then Cap Neal saved my career-got me another chance-by telling a lie-well, I guess it was a lie because it certainly wasn’t the truth. He wired Vicksburg back that no wonder I didn’t look good because they had been playing me at shortstop and my regular position was second base. The truth of the matter was that I never played second base in my life. I had been only a substitute shortstop and third baseman in high school.

“I didn’t do great,” said Herman, “but I must have done well enough because I stuck with them as a second baseman. If Cap hadn’t lied to them about my being a second baseman-I would have been sent home. Since Class D is the end of the road-and I had failed to make it at Class D-the chances are that I’d of dropped out of baseball.”7

Herman returned to Louisville in 1929. In spite of his self-deprecating approach to his abilities, statistics show that he was a solid batsman in his minor league career. His lowest average in the bush leagues was .305 in 1930. He collected 188 hits and 40 doubles. He was batting .350 through 118 games in 1931 when he was purchased by the Chicago Cubs on August 4. He made his debut on August 29, 1931, at Wrigley Field against Cincinnati, singling in his first at bat in the second inning off Si Johnson.

Rogers Hornsby was the manager as well as the regular second baseman for the Cubs in 1931. And at 35 years of age, Rajah could still hit the old ball around the ball field, batting .331 and leading the team in homers (16) and RBIs (90). But in 1932, Hornsby relinquished his keystone duties to Herman, appearing in only 19 games. The Cubs were in second place with a 53-46 record on August 2 when Hornsby was fired and replaced with Charlie Grimm. There was speculation about Hornsby’s alleged gambling, but publicly, he and club president Bill Veeck cited a difference in philosophies for running the club as the reason for Rajah’s dismissal.

Herman was not the least bit disappointed to see Hornsby exit. “He ignored me completely and I figured it was because I was a rookie. But then I saw he ignored everybody. He was a very cold man. He would stare at you with the coldest eyes I ever saw. If you did something wrong, he’d jump all over you. He was a perfectionist and had a very low tolerance for mistakes.”8It was evident that Herman was not alone in his view of Hornsby. When it came to divvying up the shares from the World Series money, the team voted to cut Hornsby out of a full or even a half share.

Under Grimm, the Cubs went 22-6 in August, 1932, and went into September leading the Pirates by 7 ½ games. They coasted through September, winning their first pennant since 1929. Herman batted .314, with 206 hits, and drove in 51 runs. But it was his defense, leading the league with 527 assists, that was surprising.

Chicago met the New York Yankees, led by manager Joe McCarthy, in the World Series. The Yankees had little trouble with the Cubs, sweeping them in four straight.

In the fifth inning of Game Three at Wrigley Field, Babe Ruth hit a home run off pitcher Charlie Root. The blast, which broke a 4-4 tie, has become known as Ruth’s “called shot”. Herman debunks this story. “If he’d have pointed and hit it there, he’d have been on his ass the rest of the series,” said Herman. “The Cub pitchers would have retaliated and sent the Babe sprawling with a blizzard of knockdown pitches. Our bench was on him, calling him everything, a big, fat baboon, everything you could think of. He was pointing toward our dugout, not to center field.”9

Over the next two seasons, the Cubs finished in second place in the National League. In 1933, Herman accounted for 466 putouts at his keystone position, still the NL record. On June 28, 1933, at Philadelphia, he tied a N.L. record with 11 putouts in a nine-inning game. In 1934, Herman was selected to his first All-Star Game. It started a string of 10 straight times that Herman participated in the mid-summer classic. He continued to hit well, despite sharing time at second base with Augie Galan, a switch-hitting infielder. By 1935 he was a fixture at the top of the Cubs order. He often batted in the two hole and was adept at hitting behind the runner when the hit-and-run play was on. Although he did not walk all that much, his walks outnumbered his strikeouts in every season. Casey Stengel pinned the moniker “John the Baptist” on Herman. “His head is always on the plate, and he cons the umpires into calling perfect strikes too high,” said Stengel.10

Billy Herman was gaining a reputation as a good, smart, aggressive ballplayer, whether at bat or in the field. “The only thing we had on our minds was to win,” said Billy. “Any way we could, we played to win. And if that wasn’t good enough, why you went back home, got a lunch pail, and go to work. If you didn’t play hard, you wouldn’t have a friend on the club and you wouldn’t be there long.”11

Herman’s views were a sign of the times. A new one-year contract had to be earned every year, and each player had to fight for his spot on the team. This was especially true during the years of the Great Depression. Another sign of the times was the presence of Al Capone at Wrigley Field. Capone would have his allotment of bodyguards around him. “The Capone era,” said Herman, “that was my time. He’d walk into the ballpark like the president walking in today, with bodyguards all around him. Once, Gabby posed for a picture with Capone. And the next year Judge Landis made a rule that ballplayers couldn’t talk to anyone in the stands.”12

The 1935 season may have been Herman’s best, as he led the league in hits (227), doubles (57) and sacrifice hits (24) while batting a career-high .341. He led second basemen in assists (520), putouts (416), double plays (109) and fielding percentage (.964). His keystone partner, Billy Jurges, led all shortstops in the same four defensive categories. Often, Herman would move a few feet, depending on the batter or the pitch count. Known as a smart player, he often played the percentages to his advantage. For players who hit most times to left field, Herman would station himself behind the second base bag. He estimated that he was successful about 70% of the time. Herman also estimated that another half-dozen times he was able to snare line drives that got by the pitcher with this positioning. For bigger, slower runners, Herman would set up shop deep on the grass between first and second base. The ball might not be hit hard, but with a slow runner, he had plenty of time to make the play.

Heading into September, the Cubs trailed the defending World Champion Cardinals by 2 ½ games. The New York Giants were in second place, one game off the pace. But the Cubs had a torrid September, posting a 23-3 record. Conversely, the Cards went 19-12 and the Giants were 15-15 in the same period. The Cubs were on top by four games as the curtain came down on the regular season.

Their World Series opponent was the Detroit Tigers. Lon Warneke pitched the Cubs to two wins, but the rest of the staff was unable to beat the powerful Tigers, who wrapped up the series in six games. For Herman, it was his most productive series, as he hit .333 and drove in a team-high six runs.

Over the next couple of years, Herman established himself as the top second baseman in the senior circuit. He was without peer in the field and at the plate he topped .300 in six of his first eight seasons as a starter. “He’s without doubt the best fielding keystone man in the league since I have been in the harness,” said manager Charlie Grimm. “He can go farther to his right and also to his left than any second sacker I’ve ever watched. Frankie Frisch, at his best, wasn’t the fielder Billy is. Frisch had more power at the plate and speed on the bases, but I’d still pick Herman over him in all-around value. “13Pittsburgh great Paul Waner said of Herman’s defense, “I’ll hit one I think is through there and Herman suddenly comes up through a trapdoor and is standing right in front of the ball.”14

The 1938 season mirrored the 1932 season in one respect. On July 19, the Cubs were tied for third place with Cincinnati. The ownership decided to make a move, replacing Grimm with Hartnett. Unlike in 1932 when the taciturn Hornsby was relieved of his duties, most people were searching for a reason why Grimm was ousted. The only explanation was that Grimm, who had led the Cubs to a 45-36 record thus far, was not getting enough out of his players. A few days later, Grimm reappeared in Chicago as a broadcaster on WBBG radio, covering Cubs games. Although it looked as if both actions were related, Cubs owner P. K. Wrigley denied it.

Chicago trailed the Pirates by 1 ½ games on September 26, 1938. But a crucial three-game sweep of the Bucs in late September catapulted the Cubs into first place and the Pirates could not recover, closing the season two games back. The middle game on September 28 was a 6-5 win, delivered by Hartnett’s solo home run in the ninth inning, which was dubbed as “the homer in the gloamin’” as darkness descended on Wrigley Field.

The Cubs faced a powerful Yankee team in he World Series. The Bronx Bombers made quick work of the Cubs, sweeping them as Red Ruffing won two games. “We come. We saw. We went home,” said Cubs first baseman Ripper Collins15

Billy Herman and Billy Jurges had formed one of the best middle-infield combinations over the last seven years. That was disrupted when Jurges was involved in a six-player deal with the New York Giants on December 6, 1938. One of the players going to the Cubs was Dick Bartell, Jurges’s replacement.

Over the next two seasons the Cubs sank in the standings. At 30 years of age, Herman showed no signs of slowing down. He led the league in triples (18) and batted .307. In the prime of his career, Herman was the king of the second baseman. In 1940, Wrigley hired Jim Gallagher as the Cubs’ general manager. Gallagher was a Chicago sportswriter who was critical of the Cubs’ front office. Wrigley offered Gallagher the job saying, “If you know so much, you run the club.”16

In 1941, Gallagher traded away Herman to Brooklyn. The Dodgers won the pennant, and again Herman found himself going up against the Yankees. The result was the same, New York winning in five games. That made Herman 1-12 in World Series games against New York.

On August 8, 1942, the Dodgers held a nine game lead over the Cardinals. The Bums seemed to be on cruise control. Incredibly, the Cards went 43-8 to surpass Brooklyn and win the N.L. pennant. “I’ll never forget,” said Herman, “we were breezing in 1942, leading by about 10 games in August when Larry MacPhail, who ran the Dodgers, came into the clubhouse and chewed out all of us, including Leo Durocher, about our drinking, card-playing, etc., and told us we wouldn’t win the pennant, that St. Louis would. We won 104 games, 104 out of 154 in those days, but Larry was right. The Cardinals went right by us and won the pennant with 106.”17

If there was ever a concern that Herman was slowing down, those thoughts were put to rest in 1943. Herman batted .330 and incredibly drove in 100 runs, a career high, while hitting only two home runs.

With World War II in full swing, players were starting to be called up to serve their country. Herman was classified 1-A, meaning that he was eligible to be drafted into the service. Instead, he enlisted in the United States Navy. After his initial training at Great Lakes Naval Station, Herman was sent to Pearl Harbor. He spent much of his time playing baseball on base teams located on the Pacific Islands. Herman missed the 1944 and 1945 seasons and was discharged on December 16, 1945.

Herman returned to the Dodgers for the 1946 season. But Eddie Stanky had taken over at second base, and on June 15 Herman was dealt to the Boston Braves for catcher Stew Hofferth. Between the two teams he hit .298 and drove in 50 runs, serving as a backup at second and third base.

Billy Herman had a desire to one day manage at the big-league level. He had wanted to lead the Cubs, but the opportunity never presented itself. On September 30, 1946, Herman was on the move again, part of a seven-player deal that sent him to Pittsburgh. There, he signed a two-year contract as a player-manager. The Pirates were in a rebuilding mode, and although they may not have been expected to challenge for the pennant, a last-place finish was also not foreseen. Under Herman, the Bucs went 61-92. They finished 32 games behind first place Brooklyn. Herman resigned on September 25, 1947. “We’re not blaming any one factor or any one individual for the failure of the Pirates. We’re not criticizing or indicting Billy Herman, but for the best interests of all concerned, Bill resigned as field manager of the Pirates,” said club president Frank McKinney. 18

Billy Herman retired with a career batting average of .304. He collected 2,345 hits, 486 doubles and 839 RBIs. He totaled 4,780 putouts, 5,681 assists and 1,177 double plays. His lifetime fielding percentage was .967. He led the National League in putouts in seven seasons.

Herman was not deterred by his managing experience in Pittsburgh. He spent the next 16 seasons either managing in the minor leagues or coaching in the majors. He was a player-manager in 1948 with Minneapolis of the American Association and in 1950 with Oakland of the Pacific Coast League. Herman then returned to the major leagues, coaching for Brooklyn (1952-1957), Milwaukee (1958-1959) and Boston (1960-1964). With two games left in the 1964 season, Herman replaced Red Sox skipper Johnny Pesky on an interim basis. He was given the head job for the 1965 and 1966 seasons. But the Red Sox finished 62-100 in 1965, 40 games back of first-place Minnesota. The 1966 season was no better, and with the Red Sox battling the Yankees, Senators and Athletics for the basement of the American League at 64-82, Herman was fired on September 8, 1966, and replaced by Pete Runnels. His managerial record was 189-274.

Herman resurfaced as a coach for the California Angels in 1967. He moved to northern California and scouted for the Athletics from 1968 to 1974.

Billy Herman was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee on August 18, 1975. “I expected it sooner, not later,” said Herman. “But I’ll take it. Sure, it’s a thrill. It’s very satisfying; particularly when you look at all the outstanding ballplayers there have been who aren’t in.”19

Herman returned to coaching, joining Roger Craig’s staff in San Diego for the 1977 and 1978 seasons. He retired to his home in Florida, with his wife Frances, whom he had married in 1961. Herman played a lot of golf, and was a 3 handicap. He enjoyed fishing and was an excellent bridge player. He passed away on September 5, 1992, in West Palm Beach, Florida as the result of cancer.

Last revised: September 29, 2023 (zp)

Notes

1 Robert W. Creamer, Baseball in 1941, Viking Press, New York, NY, 1991, 147

2 Tommy Holmes, Brooklyn Eagle, “Herman’s Brilliant Debut Sparks Flock”, May 7, 1941: 15

3 Louis Effrat, New York Times, “Herman’s Four Hits in Dodger Debut Help Defeat Pirates, May 7, 1941: 33

4 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville, St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY, 1996, 279

5 Holmes: 15

6 Tommy Fitzgerald, The Courier-Journal, “Herman Reveals His Career Was Based On A Lie”, January 19, 1955: 2-7

7 Fitzgerald: 2-7

8 Golenbock, 225

9 Jerome Holtzman, Chicago Tribune, “Cub legend Billy Herman takes stroll down memory lane in Cooperstown”, August 2, 1988: 4-3

10 Holmes: 15

11 HBO Productions, When it Was a Game, 1991

12 Holtzman: 4-3

13 Sporting News, June 17, 1937: 10

14 Holmes: 15

15 HBO Productions, When it Was a Game, 1991

16 Creamer, 117

17 Bob Broeg, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “Herman Has No Pity For Pampered Athletes”, August 17, 1975: 2D

18 Les Biederman, Sporting News, “Pirate Bosses’ Minds Open on Choice of Pilot”, October 1, 1947: 12

19 Bob Bossine, Palm Beach Post, “Billy Herman Has Big Day”, February 4, 1975: B7

Full Name

William Jennings Bryan Herman

Born

July 7, 1909 at New Albany, IN (USA)

Died

September 5, 1992 at West Palm Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.