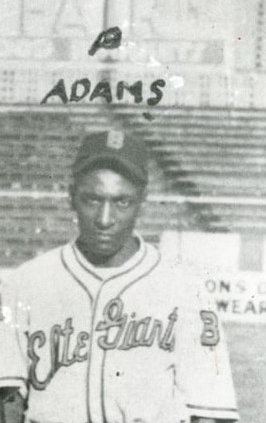

Emery Adams

Emery Adams pitched during 11 years in the top Negro Leagues, from 1932 to 1947, with military service during World War II explaining one break in his statistical record. Two earlier gaps seemingly resulted from run-ins with the law, but a jury acquitted him of the serious charge that might have cost him the entire 1936 season. His most common nickname was Ace, which he was given before the 1940 season,1 yet he really didn’t achieve like an ace during nine years in top leagues. Still, in his prime with the second-place Baltimore Elite Giants of 1940 and 1941, no other hurler excelled for them in both seasons.2 As of December 2023, all five of his career shutouts occurred in those two years, as did 17 of his 24 complete games. Also, fans voted him onto a roster for the East-West All-Star Game in August of 1940 (though he didn’t play).3 What’s more, the pinnacle of his career might have come shortly after that season, when he sparkled for multiple scoreless innings as the starting pitcher in the Negro Leagues’ sixth North-South Classic all-star game.4

Emery Adams pitched during 11 years in the top Negro Leagues, from 1932 to 1947, with military service during World War II explaining one break in his statistical record. Two earlier gaps seemingly resulted from run-ins with the law, but a jury acquitted him of the serious charge that might have cost him the entire 1936 season. His most common nickname was Ace, which he was given before the 1940 season,1 yet he really didn’t achieve like an ace during nine years in top leagues. Still, in his prime with the second-place Baltimore Elite Giants of 1940 and 1941, no other hurler excelled for them in both seasons.2 As of December 2023, all five of his career shutouts occurred in those two years, as did 17 of his 24 complete games. Also, fans voted him onto a roster for the East-West All-Star Game in August of 1940 (though he didn’t play).3 What’s more, the pinnacle of his career might have come shortly after that season, when he sparkled for multiple scoreless innings as the starting pitcher in the Negro Leagues’ sixth North-South Classic all-star game.4

Emery Adams was born in the vicinity of Collierville, Tennessee, on October 10, 1911, according to his 1940 military registration card. Collierville is about 20 miles from Memphis. Based partly on the censuses from 1900 to 1920, his parents were farmers named Sam and Polly. Sam’s entry in the 1900 census stated that he was born in South Carolina during 1845 and thus 16 years prior to the Civil War. He was presumably a slave well into his teens. Sam would have been 66 when Emery was born. Polly was much younger, reportedly born in 1870 in Mississippi.

The 1910 census indicated that it was the second marriage for both of Emery’s parents. In early 1899, a Memphis newspaper noted that a “Colored” couple, Sam Adams and Polly Williams, had obtained a license to be married.5 However, her death record and Emery’s 1948 certificate of marriage, among other documents accessible via genealogical websites, identified Polly’s maiden name as Butler. Emery apparently had at least five half-siblings born before 1900 and was the youngest of at least four children born to Sam and Polly. In the 1910 census, Polly was reported to have given birth to five children, of whom four were still living.

In the 1920 census, Emery and his two brothers, ages 12 and 13, were all reported as attending school. In the 1940 census, it was stated that Emery had completed one year of high school. A history of Collierville focusing on civil rights noted that a school for Black children opened in Collierville during the 1920s.6 It was rarely mentioned in Memphis’s daily newspapers, but the “Collierville Industrial School, a negro institution,” existed by the summer of 1923, if not earlier.7 It was called the Collierville Industrial Junior High in an article five years later, about its students’ participation in the “eighteenth annual negro Tri-State Fair.”8

Census records show the township’s population in 1920 and 1930 hovered around 1,000.9 During that decade, farming operations in the Collierville area began to shift dramatically, as boll weevil beetles began to devastate cotton crops. Over just a few years, up to 1929, the number of dairies in Collierville jumped from a handful to several hundred.10 Sam Adams was identified as a farmer up to the time he died.

The elder Adams’s Certificate of Death, accessible via genealogical websites, indicates that he died in nearby Germantown on February 9, 1929. In the following year’s census the Adams household comprised Polly, Emery, and one of his brothers. Polly was still listed as a farmer, while Emery’s occupation was farm helper.

Emery Adams got married on July 8, 1930, in the county of his birth. The marriage license reported his bride’s name as Emma Bell Hull. They were husband and wife for no more than six years. The couple apparently had one child together, a girl named Virginia, also known as Annie Virginia. She was reportedly born September 1, 1933.11

However, Emery’s obituary noted that he was also survived by a son, Emery Jr. Two Social Security records agree that Junior’s birthday was August 8, but one showed 1932 and the other 1933. Though Emery Jr. was likely older than Virginia, he was born to a different mother, Lula M. Craft. Because her mother was also named Lula, Junior’s mother was often called Mary or Mattie instead. She and Emery Senior might never have married one another.12

Emery Adams turned 20 years old during the autumn of 1931, and six months later he was pitching for the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro Southern League. Though it seems very likely that he had considerable baseball experience prior to 1932, there might be no records in existence documenting any of that. The Red Sox received decent coverage in newspapers during 1931, but dailies in that city rarely mentioned any Black semipro or amateur teams.13 Among more than 30 players on the Red Sox at some point during 1931, none was named Adams.14

The NSL was generally considered Black baseball’s top minor league for much of its existence, but for the 1932 season it is considered to have been a “major league,” a status officially recognized by Major League Baseball in 2020.15 For just that one season, the NSL included two prominent Northern teams, the Chicago American Giants and the Indianapolis ABCs, plus a short-lived club in Columbus, Ohio. In fact, in the second game of a preseason doubleheader at home on April 17, Adams shut out Chicago, 3-0, in a game limited to five innings so the visitors could catch a train. He gave up just two singles, walked one batter, and struck out four.16

Emery Adams made his regular-season debut as a pro on May 1, 1932, in a doubleheader against the first-place Monroe (Louisiana) Monarchs. He was 20 years old. He started the seven-inning second game, and in the bottom of the third frame his team gave him a 3-0 lead. The only other scoring was a pair of runs by Monroe in the top of the fifth. Details of that inning aren’t available, except that Adams retired just one batter before being replaced by a reliever. He struck out two Monarchs and yielded only two hits, but his three walks may have contributed to Monroe’s threat in that fifth frame. (Also, each of Memphis’ middle infielders made an error at some point, and the home team’s catcher was charged with a passed ball.) Adams did contribute a little on offense: Though he was hitless in one at-bat, he stole a base and scored a run.17

As the 1932 season unfolded, only Harry Cunningham and player-manager Goose Curry logged more innings than Adams as starting pitchers for Memphis, based on seamheads.com data as of 2024. He started 10 of 11 games, completed four, and had a 4-3 record.18 He was on the wrong end of a shutout at least twice, in May and in July.19

Memphis’s stats in the Seamheads database jump to 1937 because the NSL reverted to minor-league status after 1932. In 1937 the Red Sox joined the Negro American League. However, from 1933 to 1936, William J. Plott’s painstaking history of the NSL listed Emery Adams on the club’s roster only in 1935, though in 1936 the club did have a pitcher named Adams (first name unrecorded) during April, if not later.20 The 1933-1934 and 1936 gaps in Adams’s personal record might be explained by Memphis newspaper reports about legal action against a local man (or men) named Emery Adams.

On February 6, 1933, “Emery Adams, negro,” was prosecuted for “assault to murder, because of a fusillade of shots fired at W.B. Sandlin, marshal of Germantown, Dec. 21.” In the end, he “pleaded guilty to assault to commit second degree murder, not more than three years at the penal farm.”21 Though Adams was mentioned often during 1935 as a member of the Memphis Red Sox, that name instead showed up in local legal news in 1936, from April 25 into October. A companion of Adams received a 10-year prison sentence for the shooting death of another Black man named Martin Hill, but Adams himself, “who was jointly accused of the crime, was found not guilty by a jury in Judge Tom W. Harsh’s criminal court.”22 Assuming this relieved defendant was the Red Sox pitcher, then he celebrated his freedom the following month by getting married. His wife was the former Floyd Myers (an uncommon first name for a woman, but the November 22 marital record accessible via genealogical websites isn’t the only place it was rendered that way).

“Statistically, the 1935 season was the worst ever” for the NSL, Plott insisted, because “results of any kind were found for only 33 league games.” Plott said Bill Howard was the winning pitcher in all seven Memphis wins he’d located, but on June 30, Adams had an impressive victory in the second game of a doubleheader (following a win by Howard): He shut out the Claybrook (Arkansas) Tigers in a seven-inning contest, 1-0. Overall, Memphis did well enough to qualify for a postseason playoff series, which it lost to Claybrook.23

Adams pitched a few times against Claybrook in September. On September 1 Claybrook took both games of a doubleheader “to claim the National semipro championship,” as reported by the Chicago Defender. In defeat, “Adams, the Memphis hurler, had a fair day on the hill, tossing the apple by the batters for strikeouts in usual manner.”24

Coverage later in the month indicates the doubleheader was part of a seven-game series to determine the NSL championship. Adams relieved in both games of a doubleheader in Claybrook on September 8, which the teams split.25 The teams had each won three games by September 15, when nearly 3,000 fans in Memphis attended the finale, which the home team lost, 5-2.26

Another mystery relating to Adams during the 1935 season was whether he was the Bill Adams who was with Claybrook briefly. If so, he was in the front row of a team photo that season.27 “Bill” was a secondary nickname for Emery Adams, though possibly not otherwise in print prior to 1941.28

Regardless, September ended on a high note for Adams, when he pitched in the very first North-South Classic all-star game. It was played on September 29, at Memphis’s Russwood Park before 3,800 fans. Adams pitched the final two innings for the South, against a lineup that included future Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell leading off and Oscar Charleston batting cleanup. Adams allowed just one hit and was the only hurler on either team not to yield a run.29

On April 15, 1936, a preview of a game against the Monroe Monarchs mentioned Adams as one of two Memphis pitchers. On April 26 Adams was Memphis’s reliever against a Black team visiting from Omaha.30 It was two mornings earlier when the aforementioned Martin Hill, a Black man residing in Germantown, was shot to death by an unknown person. At some point within a month Adams and a companion were formally accused, but clearly not prior to his team’s game on the 26th.31 Though he was found not guilty in October, Adams may have been jailed for about half of that year due to the serious nature of the charge.32

As noted previously, for the 1937 season the Memphis Red Sox switched from the NSL to the NAL. Adams hurled a complete-game 7-6 victory at home against the Chicago American Giants on Opening Day, May 9. That gave the Red Sox a split of a doubleheader.33

As of 2024 the Seamheads database had data for 20 Memphis games in 1937, only one of which was a victory by Adams (in four appearances). However, in addition to that Opening Day win, brief newspaper coverage indicates he had a complete-game win vs. Indianapolis on May 17 and beat the St. Louis Stars later that month.34 Also not documented in Seamheads is a game in August when he helped beat Birmingham by swatting a 10th-inning double (although he didn’t pitch).35

A preview of a game late that month said “Adam [sic] hurled for the New Orleans Black Pelicans before joining Memphis.” Unclear was whether that meant before he first joined Memphis in 1932, or before he rejoined the club much more recently.36 Regardless, searches for a pitcher named Adams on that club prior to mid-1937 were fruitless.

To date, the Seamheads database shows just one game in 1938 for Adams, a four-inning relief outing for the Red Sox. In fact, that game was a preseason exhibition at home on April 3, a 7-3 loss to the Homestead Grays. The Atlanta Daily World printed a batter-by-batter account, though it wasn’t clear in which middle inning Adams entered the game. He was mentioned again in a preview on April 16, but might not have been with the Red Sox during the regular season.37 One distinct possibility is that he was injured. Another explanation is that he was making steady money at another job: Memphis’s 1938 and 1939 city directories show him as employed by the Memphis Power and Light Company.

In any case, in 1939 Emery Adams played his first games in the second Negro National League, as a member of the Baltimore Elite Giants. As of 2024 the Seamheads database has documented five games pitched by Adams during that regular season, including two victories, plus a playoff loss. Using different criteria, the timeline for SABR’s book on the 1939 Elite Giants identified 19 games for Adams from May through August (though at least six were nonleague contests).38

A high point for Adams during the season’s first half was in June 12 in Indianapolis, against the Homestead Grays, reportedly the league’s preseason favorite. It certainly helped that the famous Josh Gibson was unavailable due to a bruised hip, “but Adams, ace right-hander for the Giants, refused to allow the Champs a chance to get a line on his famed smoke ball.” He struck out 11 Grays on the way to a 7-3 win for Baltimore.39

Not long before the NNL playoffs, Adams notched a complete-game win at home against the New York Cubans on August 27. It was the seven-inning nightcap of a doubleheader, and the final score was 8-4.40 He then started the first game of a best-of-five playoff series against the Newark Eagles on September 6, at the opposition’s Ruppert Stadium. After the top of the fourth inning, Adams and his teammates led 5-0, but Newark scored eight runs by the end of the sixth inning and ultimately won, 8-6.41 The Seamheads entry for this game shows Adams having retired one batter in the sixth before exiting. He was charged with giving up seven runs, five earned. There’s no record of Adams playing in the championship series against the Grays, but on September 24 the Elites became the NNL champs.42 Though Adams pitched a half-dozen more seasons in the NNL, there’s no indication that he ever appeared in another playoff game.

In the 1940 census, Emery and Floyd Adams were living in Memphis in the home of her mother, at 2563 Spottswood Avenue, near a very large railroad yard. Adams earned his nickname of Ace that year. The Seamheads database shows him as having won 12 games and lost five for the Elite Giants.

In June he tossed a 6-0 shutout against the Philadelphia Stars in a doubleheader’s seven-inning nightcap, and his nine-inning shutout against the New York Cubans about a week into September won the Ruppert Memorial Cup for the Elites again.43 In between those two high points, he was the only Baltimore pitcher named to the East team’s roster for the East-West Classic in August, though he didn’t play.44

The peak of Adams’ career might have come shortly after the 1940 season. At New Orleans’ Pelican Stadium on October 1, he sparkled for multiple scoreless innings as the starting pitcher in the Negro Leagues’ sixth North-South Classic all-star game, though sources disagree on whether he pitched the first four or five innings. Regardless, the game wasn’t decided until the ninth, when his North teammates scored once to break a 1-1 tie.45

Adams was on the Cienfuegos club in Cuba’s winter league during 1940-1941, but he couldn’t approximate his success of recent months. In 14 games, he had a record of 2-6.46 In fact, a passenger list accessible via genealogical websites shows Memphis resident Emery Adams (born October 10, 1911) as having sailed from Havana to Miami on January 2, 1941. At least three Cienfuegos teammates made the same trip on January 20.

The 1941 season was the second of Adams’s career for which the Seamheads database has documented considerable success. Though data is available for fewer games, his winning percentage with a record of 7-3 for Baltimore was comparable to that of 1940, with three shutouts documented in 1941 compared with two the prior season. One 1941 shutout was pitched on July 12 against the Newark Eagles and another on September 1 against the Black Yankees.47

Adams’s 1942 season was largely unremarkable until a five-game “do-or-die series” with the Philadelphia Stars at the end of the season, which found the Elites hanging onto pennant hopes. Adams lost games in relief on September 6 and 7, and thus ended Baltimore’s season.48

During spring training in 1943, the Baltimore Afro-American’s sports editor, Art Carter, reported that Adams was “on the market as trade material.” And by early May he’d been purchased by the Black Yankees.49 Adams had at least four awful starts before the end of June, in which he pitched no more than five innings yet gave up 7 to 13 runs, Not surprisingly, he was called upon to pitch much less from July onward, but instead was frequently in New York’s lineups as an outfielder. The Philadelphia Stars borrowed him as their starting pitcher on September 12, but he was back in New York’s outfield within 10 days.50 In fact, it was reported on September 20 that his batting average of .350 was the best among the Black Yankees.51

Less than three months into 1944, Emery Adams’ life took a dramatic shift. US Army enlistment records accessible online show him having started military service on March 27. The military registration card he’d completed back in 1940 included a handwritten note specifying that he received an honorable discharge on September 9, 1944. Vaguely, the stated reason was “a lack of adaptability for military service.”52 If Adams played a little pro ball in the weeks after his discharge, it might have gone unreported.

Adams returned to the Black Yankees for the 1945 season, but was rarely used as a pitcher. In February of 1946, Adams was to be on a team projected to tour the Pacific for three months, playing against military ballclubs. The announced leader as Joe Lillard, a Black halfback for the NFL’s Chicago Cardinals in 1932 and 1933, who’d helmed such a tour in Asia a year earlier. Very shortly after the 1946 trip was announced, it was “postponed indefinitely.”53 Adams then saw minimal action that season with New York, and likewise in 1947. That was apparently the extent of his pro career.

In 1948 Adams married for (at least) the third time. A Delaware certificate of marriage accessible via genealogical websites shows him marrying Irene Geter of New York City on March 21. The document presumably had a few details wrong (e.g., he’d been single, it was his first marriage, and he was born in Delaware), but his birthdate matched. In the 1950 census, the couple was living near a relative of hers in New York City, and he was employed as an inspector at a television factory.

Emery and Irene presumably divorced by mid-1952, because in October of that year she was identified by her maiden name, Geter, in a newspaper article detailing how she was swindled out thousands of dollars a few months after a personal-injury lawsuit. In June, attorneys won her $40,000 for a leg amputation that resulted from a bus accident, and after their fees and court expenses, she took home $15,000. A con man cheated her out of that entire amount, though police did catch him.54

Emery Adams died “suddenly” in New York on January 22, 1955. His obituary published in Memphis mentioned that he was survived by daughter Virginia and son Emery Junior. There was no mention of any spouse, and his two surviving grandchildren were unnamed. (Of course, his daughter and son could have had additional children after his death.) He was survived by a sister and three brothers, all of whom were named with their places of residence. The funeral director was back in Collierville.55

Almost 60 years after his death, Adams was reportedly the central figure in an auction of a “Negro League game-used uniform,” which had “E. Adams” written in marker near the manufacturers’ tag. Grey Flannel Auctions of Scottsdale, Arizona, attributed it to Adams, and dated it in the mid-1930s. However, the tag identified the producer of this Memphis Pros jersey as Lawson-Cavette, a Memphis sporting-goods firm that had changed its name from Lawson-Getz during the summer of 1948. This would seem to indicate that for at least one season after leaving the Black Yankees, Adams went back home to play more baseball. At the time, he couldn’t possibly have imagined that this jersey would have been purchased at the end of 2014 for $1,420.56

Sources

Information about Adams’s personal life is from Ancestry.com (Library Edition) and FamilySearch.org.

Except when contemporary coverage of games is cited in endnotes, the sources for his statistics and individual game performances are the Seamheads database, starting at https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=adams01eme and the Retrosheet website, starting at https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=adams01eme.

Notes

1 For example, he was called “Ace” in the preseason article, “Elites to Open Against Stars,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 11, 1940: 21.

2 See https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=adams01eme. In 1940 and 1941, Adams was the only pitcher to start more than six games each season for Baltimore, as of research up to 2024.

3 “Homers May Decide East-West Classic,” Chicago Defender, August 17, 1940: 24. See also https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1940/B08180ASW1940.htm.

4 See https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1940/B10010SAS1940.htm.

5 “Licensed to Wed,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, February 18, 1899: 7.

6 Collierville Community Justice, “We Can’t Understand Collierville’s Present Without Understanding Collierville’s Past,” https://www.colliervillejustice.org/history. This history reported no race-related incidents in the twentieth century until the mid-1960s.

7 “County Fighting Malaria,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, August 30, 1923: 8.

8 “Negro Fair Promises Best Show Yet Held,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, October 25, 1928: 14. The school was occasionally mentioned in articles published by Black newspapers, such as “Popular Teacher Bids Farewell to Classroom as Cupid Beckons,” Atlanta Daily World, September 21, 1936: 3.

9 See https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/33973538v1ch09.pdf at page 1022.

10 Town of Collierville, “Collierville the Dairy Town,” https://www.colliervilletn.gov/government/town-departments/morton-museum/exhibitions/collierville-the-dairy-town.

11 In particular, see “Death Notices,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, January 26, 1955: 30. Emma’s Certificate of Death in 1953, which identified her by widower husband’s surname of Allen, said she was the daughter of Jim Hull and Rosie Green. She was using her mother’s surname in the 1940 census and was Mrs. Allen by the 1950 census, both of which included daughter Virginia in her household. As of 2024, an Ancestry.com family tree for Emma B. Hull identified three of her children, namely Willie Mae Franklin, Rosie Lee Gray, and Roscoe Lindsey. The latter’s obituary in 1981 reported that he was survived by Willie Mae Franklin and Rosie Lee, plus a third married sister, Mrs. Annie Virginia Beard. See “Deaths,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, August 21, 1981: 16. The Beard family tree on Ancestry.com identified Adams as her maiden name and said she had been born in Germantown on September 1, 1933, information that quite possibly came from the woman herself.

12 “Death Notices,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, January 26, 1955: 30. See also two Social Security Applications and Claims Index entries for Emery Adams Jr., accessible via genealogical websites. In the 1940 census near Memphis, he is presumably “Emory Byas,” 6-year-old brother of Katy May Byas, son of 23-year-old Mary Byas, and grandson of 55-year-old Lula Craft, the head of that household. Another half-sister’s obituary mentioned being survived by two brothers, “Emery Adams and Charles Byas.” See “Mary G. Williams,” Michigan Chronicle (Detroit), October 22, 1997: D-6.

13 For example, when the Red Sox scheduled an exhibition game against the Chisca Hotel Bears, one Memphis paper said the latter was “probably the best negro amateur club in the city.” However, there seems to be no record of any Memphis daily actually reporting on any of that team’s games. See “Red Sox to Play Bears,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 19, 1931: 15. (It’s likely the game wasn’t played that day, based on “Chicks, Barons Rained Out; Kelly vs. Edwards Today,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 20, 1931: 16). For a rare example of a Black amateur game that received publicity as well as some coverage in Memphis dailies that year, see “Negro Barbes Lose,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, September 15, 1931: 15.

14 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2015), 217.

15 Anthony Castrovince, “MLB adds Negro Leagues to Official Records,” December 16, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/news/negro-leagues-given-major-league-status-for-baseball-records-stats.

16 “Red Sox Win Two More from Chicago; Open Season Friday,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, April 18, 1932: 9.

17 “Red Sox Win Two Games from Monroe; End Series Today.”

18 See https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=adams01eme; click on “MRS” next to 1932 for the team’s record.

19 Holsey Drake, “Montgomery Had a Word for Memphis Reds,” Atlanta Daily World, May 15, 1932: 5. “Memphis Red Sox 9 Split 2 with Monroe,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, August 1, 1932: 7. The latter shutout ended 1-0.

20 Plott, 222, 224, 225-226, and 227. “Red Sox Play Monroe,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, April 15, 1936: 19. “Memphians Down Omaha Negro Club,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, April 27, 1936: 13.

21 “Auto Theft Trials Will Open Tomorrow,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, February 5, 1933: 20. “News in the Courts,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, February 7, 1933: 16.

22 “News of the Courts,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 27, 1936: 25. News of the Courts,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, June 18, 1936: 27. “Negro Sent to Prison,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, October 23, 1936: 21.

23 Plott, 133-134. “Claybrook Loses Pair to Memphis,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, July 1, 1935: 14.

24 Robert Ratcliffe, “Arkansas 9 Cops Semi-Pro Baseball Title,” Chicago Defender, September 7, 1935: 14.

25 “Negro Red Sox Split Two,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, September 9, 1935: 11.

26 “Clay Brooks in 5 to 2 Victory,” Chicago Defender, September 21, 1935: 15. This article identified all dates, locations, and results of the series, though it didn’t report the final scores. The Defender might have provided the most detailed coverage, but it left readers with a minor mystery. “The Red Sox were forced to use two pitchers,” that weekly noted, the second of whom was Howard. “Five errors by [Red] Longley, Sox second baseman, and wild pitching by Adams accounted for three of the Tiger scores,” the paper added. However, the line score’s battery for Memphis instead listed its starting pitcher as R. Jones, not Adams. One possibility is that Jones did start and Memphis used two relievers, not just two pitchers all told. However, player-manager Ruben Jones wasn’t known at all as a pitcher, so the inclusion of him in the battery was most likely just a mistake.

27 For the 1935 Claybrook Tigers’ photo that included a Bill Adams, see http://arkbaseball.com/tiki-index.php?page=Claybrook+Tigers.

28 Adams was called Bill in “Stars Wopped by Elites,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 10, 1941: 1.

29 See https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1935/B09290SAS1935.htm, though it doesn’t appear to align completely with the box score that accompanied the brief account, “North Downs South in All-Star Battle,” Commercial Appeal, September 30, 1935: 13.

30 “Red Sox Play Monroe,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, April 15, 1936: 19. “Memphians Down Omaha Negro Club,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, April 27, 1936: 13.

31 “Negro Slain,” Commercial Appeal, April 25, 1936: 5. “News of the Courts,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 27, 1936: 25.

32 “Negro Sent to Prison,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, October 23, 1936: 21.

33 “Red Sox Split Two with Chicago Team,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 10, 1937: 11.

34 “Memphis Red Sox Win,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, May 18, 1937: 16. “Memphis Is Too Much for St. Louis 9,” Chicago Defender, May 29, 1937: 13.

35 “Memphis Wins,” Chicago Defender, August 14, 1937: 22.

36 “Negro Teams Meet Monday,” Decatur (Illinois) Daily Review, August 28, 1937: 15.

37 “Josh Gibson Two Home Runs Wellmaker’s Hurling Beats Memphis Red Sox, 7 To 3,” Atlanta Daily World, April 5, 1938: 5. Sam R. Brown, “Philly Stars Meet Redsox,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 16, 1938: 16.

38 Bill Nowlin, “1939 Baltimore Elite Giants Timeline,” The 1939 Baltimore Elite Giants (Phoenix: SABR, 2024).

39 “Grays Bow 7-3 to Baltimore With Gibson Out of Line-up,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 17, 1939: 14.

40 Ralph F. Boyd, “Elites and Cubans Split Twin Bill,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 2, 1939: 23.

41 “Mule Suttles Slugs Hard,” Newark Evening News, September 7, 1939.

42 “Elites Win, 2-0, in Colored Final,” New York Daily News, September 25, 1939: 40. Adams did remain with the Elites after the Newark series, having started an exhibition game midway through the championship series. See John G. Palmer, “Bushwicks, Met. Champions, Win From Negro League Champs, 3 to [sic],” Brooklyn Citizen, September 20, 1939: 6. To complete that headline, the score was 3-1. Palmer reported Adams’s first name as Cliff.

43 “Box Scores,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 13, 1940: 11. “Grays Win Over Memphis, 3-1,” New York Daily News September 9, 1940: 40. For details about the Ruppert Cup, see a few paragraphs into an article by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Library Associate Bill Francis, “Negro Leagues Photos Now Available Online through Pastime,” https://baseballhall.org/discover/negro-leagues-photos-now-available-on-pastime.

44 See Note 3.

45 See https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1940/B10010SAS1940.htm (which shows Adams as having stolen a base). At least one article said Adams pitched five innings. See Hayward Jackson, “Mackey’s Single Helps North Beat South, 2-1,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 12, 1940: 18. At least one box score also showed he pitched five innings. See “North Wins 2-1 Game From South in N. Orleans,” Chicago Defender, October 12, 1940: 24. However, the box score accompanying the latter incorrectly called Adams the winning pitcher, while omitting that actual pitcher of record, Baltimore teammate Bud Barbee. At least one preview of this game stated, incorrectly, that Adams had earlier started that summer’s East-West Classic, but he didn’t pitch in it at all. Contrast https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1940/B08180ASW1940.htm with Hayward Jackson, “North-South Baseball Classic for Crescent City October 1,” Atlanta Daily World, September 21, 1940: 5.

46 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003), 239.

47 Details relating to the two shutouts are available via https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1941/Padame1011941.htm. In contrast to Adams’s Seamheads line for 1941, the Retrosheet list for Adams in 1941 currently shows him with only two shutouts and only five regular-season wins (plus an exhibition win against the Birmingham Black Barons on August 11). Conversely, Retrosheet shows him with two regular-season losses plus two in exhibition games.

48 “Elite Hurlers Face Tough Task in Philly Series,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 5, 1942: 25. “Grays Win NNL Flag; Elites Split,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 8, 1942: 19. See also the September 6 and 7 entries at https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1942/Padame1011942.htm.

49 Art Carter, “Adds to Elites’ Problems as Camp Opens,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 17, 1943: 24. “Baseball Bits,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 8, 1943: 26. The latter article called him “John (Ace) Adams.”

50 See his Pitching Log outings of May 15, May 25, June 20, and June 24 at https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/A/Padame101.htm. His Batting Log is also accessible there. According to a profile posted online by the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, citing author John Holway, Adams also lost a game for Philadelphia in 1940, in addition to 1943. However, no such game has been logged by Seamheads or Retrosheet. See Dr. Layton Revel, “Forgotten Heroes: Roy ‘Red’ Parnell,” 2018, at http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Roy_Parnell%202019-10.pdf .

51 “Black Yanks Here for Tilt Tomorrow With Memphis Nine,” Muskogee (Oklahoma) Times-Democrat, September 20, 1943: 11.

52 A little more specifically, it’s possible he was labeled with some sort of “personality disorder,” as was another veteran of that war as described in a published case, at https://www.va.gov/vetapp08/files2/0816194.txt.

53 “Joe Lillard to Take Negro Ball Club on USO-Camp Show Tour,” Cleveland Call and Post, February 2, 1946: 8B. “Delay Star Nine’s Overseas Tour,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 2, 1946: 22.

54 “Woman Swindled – 15Gs,” New York Amsterdam News, October 25, 1952: 1.

55 “Dead,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, January 26, 1955: 23. His obituary in Memphis dailies (see Notes 11 and 12) spelled his first name as “Emory.” His daughter was identified as “Mrs. Virginia Moore” but attempts to determine the first name of her husband then have been unsuccessful. However, in 2008, she became the widow of longtime Memphis resident George Beard Sr.; see “Deaths,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, November 6, 2008: DSA4. Around 1970, Emery Junior was married to the former Alma Jean Arnold, according to Perry O. Withers, “50th Wedding Anniversary,” Tri-State Defender (Memphis), August 1, 1970: 8.

56 See https://greyflannelauctions.com/Mid_1930s_Memphis_Pros_Negro_League_Game_Used_Unif-LOT33011.aspx. It’s quite possible the Memphis Pros baseball club was never mentioned in local newspapers.

Full Name

Emery Adams

Born

October 10, 1911 at Collierville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.