Ruppert Stadium (Newark, NJ)

This article was written by Curt Smith

If “What’s past is prologue,” as Shakespeare wrote,1 Ruppert Stadium’s in Newark began with Charles A. Davids, a Bayside, New York, promoter.2 To most of the public, though, it begins with the baseball original for whom the park was named, ultimately housing two teams so good that to some they seemed better than several teams in either major league.

In 1925 Davids bought the Reading, Pennsylvania, franchise in the Eastern League for a reported $80,000 and moved it to Newark.3 He then paid $125,000 for the land to build a new park — the modestly named Davids Stadium — for his Newark Bears of the International League in the city’s section now known as the Ironbound4 due to its numerous railroad tracks. For inspiration, Davids used the grandstand footprint of the wooden Wiedenmeyer’s Park, home of the Newark Indians in the 1908-11 Eastern League and 1912-16 International League, which earlier that year accidentally burned to the ground and left only the playing field.5 On one hand, Davids re-created its 12,000-seat single tier. On the other, lightly leveraged, he was soon missing bills.

By 1927, Newark Star Eagle publisher Paul Block bought Davids Stadium and the International League Newark Bears for $360,000 plus $160,040 in debts.6 Ultimately, “with rumors flying like saucers that Block [too] was losing money,” read an Associated Press story, “and that Brooklyn was going to take over,” baseball’s most famous owner thwarted the Dodgers by buying the Bears franchise for $360,000 in 1931.7 The Yankees’ Jacob Ruppert inherited Newark (a.k.a. Bears) Stadium, in 1932, renamed it Ruppert Stadium,8 upped capacity to 19,000, and built “the golden era of Newark baseball and 18 years of perhaps the most successful farm club operation organized baseball ever will see,” said the New York Times.9

From 1926 to 1949, Ruppert Stadium housed seven IL pennants, four Governor’s Cups (a.k.a. playoff crowns), and three Junior World Series titles.10 Before the Cubs bought and moved the team in 1950, Hall of Famers Yogi Berra and Joe Gordon played there — also Jerry Coleman, Tommy Henrich, and Red Rolfe.11 Many deem the 1937 Bears the best minor-league nine of all time. Meantime, the ballpark’s other regular, the 1936-48 Newark Eagles, became the Negro Leagues’ gold standard with Class of Cooperstown Leon Day, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, and Effa Manley.12 In 1946 they beat the Kansas City Monarchs of Satchel Paige and Buck O’Neil in likely the greatest Negro World Series. Like Jacob Ruppert, this Newark team’s owner was gargantuan in her effect. Manley was called “The Queen of the Negro Leagues.”13

“What symmetry!” said Jim Gates, 1995 librarian of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “Jacob Ruppert and Effa Manley, both inducted at Cooperstown. The Bears dominate the International League the same 1930s decade [a poll also included the 1932, 1938, and 1941 clubs among the minors’ 100 best-ever teams14] as Newark joins the Negro Leagues. An historic team rises in each league in the same city” — a nonpareil urban twinning of the heart. “You didn’t need to go across the river to see Hall of Famers bloom in New York. Then both teams leave Newark at about the same time,” the Bears moving to Springfield, Massachusetts; the Negro National League disbanding at about the same time as the Eagles left for Houston in late 1948. “You can look it up,”15 Casey Stengel said, famously. In New Jersey, you don’t need to.

Ruppert Stadium’s odyssey starts with its namesake’s Yankees dynasty and its Double-A club. (The Bears turned Triple A in 1946) Much of America’s nineteenth-century immigrant populace was said to be figuratively born to beer. Ruppert was literally born — the second-oldest of six children of brewer Jacob Ruppert Sr.16 and his wife, Anna, in the New York City of August 5, 1867. A second-generation American who spoke with a German accent all his life,17 he grew up on Fifth Avenue, attended the Columbia Grammar School, and joined his dad’s brewing business at age 20 in 1887 as a barrel washer working 12 hours a day for $10 a week18 to become brewery VP and general manager. In 1886 Ruppert began a parallel military career, entering the Seventh Regiment of the New York National Guard. In 1890 he leapt to the rank of colonel, by which he was known the rest of his life. Ruppert then joined the staff of two governors of New York, David Hill and Roswell Flower. In 1898 he was elected as a Tammany Hall-backed Democrat to the US House from New York’s 15th Congressional District.19 The Colonel was re-elected in 1900.20 He was then twice elected from the 16th District,21 decided not to run again in 1906, and left office a year later.

In 1914 the politician/military man bought J&M Haffen Brewing Company for $700,000, hoping to close the brewery down and start a career of development in the Bronx.22 On his father’s 1915 death, Junior inherited the Jacob Ruppert Brewing Company and became president, decided to spend much of it on the boyhood love he had had little time to enjoy since grammar school. Several times Ruppert had vainly tried to buy John McGraw’s New York Giants. In 1912 he had a chance to get the Cubs — but, thoroughly New York in taste and fashion, cavalierly dismissed the Midwest as a time zone too far.23 In early 1915, the Colonel barely had to leave the neighborhood to meet Frank J. Farrell and William S. Devery, owners of the recently redubbed American League New York Highlanders-turned-Yankees.

Today, given the Yankees’ fame, it is hard to envision how they once suggested Ring Lardner’s barb, in another context, as someone who “looked at me as if I were a side dish he hadn’t ordered.”24 In 1903-12, the Highlanders had forgettably played in Hilltop Park, moving in 1913 to the Giants’ Polo Grounds as a tenant. Even so, in 1915 Ruppert and his co-owner, the gloriously named Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston, a former US Army engineer and colonel, paid $460,000 and assumed another $20,000 in debt for the club.25 On paper, the martial pair had made the big leagues, but they didn’t stay matched for long. In late 1917, AL President Ban Johnson urged Ruppert to hire manager Miller Huggins. Huston, then in Europe, loathed Huggins, favoring a drinking pal, Brooklyn skipper Wilbert Robinson. Ruppert didn’t care, giving Huggins a two-year contract before Huston got home.26 The rough patch was never patched up, one colonel, Ruppert, buying the other out for $1.5 million in 1922.27

By then the Pinstripes had acquired a player who changed everything, so much that in the July 12, 1999, Sports Illustrated, Richard Hoffer likened Babe Ruth to “rock-and-roll and the Model T … a seminal American invention. Be it his power at the plate, his popularity or his various appetites, the Babe was huge.”28 The Yankees won pennants in 1921-22 — their first of 40 through 2018, easily the most of any professional North American team. Furious, Giants owner Charles Stoneham raised the Yanks’ rent for 1922 and, in effect, kicked the American Leaguers off Manhattan Isle. “They should move to some out-of-the-way place like Queens,” huffed the ‘Jints’ McGraw, presuming no one would ever hear from them again.29 Irate, Ruppert bought land across the Harlem River for $675,000 from the estate of William Waldorf Astor.30

That year construction of the first baseball field to be called a stadium — Yankee Stadium — rose in 284 working days one-quarter mile from the Polo Grounds.31 The Bronx Bombers baptized it by winning the 1923 World Series and encoring in the 1927-28 fall classic — through 2018, their 27 World Series titles also a North American high. As sole owner, Ruppert pioneered team uniforms in 1929;32 made Joe McCarthy skipper in 1931; swept the 1932 Series from Chicago; and forged a sublime farm system to give his dynasty near-perpetuity.33 Newark was its hub. The ballpark named after him rose on a 15-acre plot of land near the Lehigh Valley Railroad in southeast Newark on 262 Wilson Avenue and Delancy Street in the vicinity of the Passaic River, Newark Bay, and the present Newark Liberty Airport.34 For 13 years after 1935, Newark’s two great baseball clubs shared it peaceably and memorably — indeed, to columnist Jerry Izenberg, “shared pieces of its [Newark’s] heart and soul.

“These two teams wrote history of this town,” Izenberg wrote movingly in the Newark Star Ledger. “They won the world championships of their social sets, and a dozen of baseball’s Hall of Famers played for them. They were the kings of a city where every 8-year-old could explain the infield fly rule — where you could walk down the city’s summer-night streets when the Bears played and through the open windows hear the radio voice of a man named Earl Harper — [and] where a remarkable reporter named Jocko Maxwell” observed Newark’s “other players … great African-American players like Leon Day and Willie Wells and Ray Dandridge, whose only flaw in the eyes of Major Leagues Baseball was that they had been born too soon.”35

Most of these players had begun to play in the 1920s, or before. By decade’s end, with the majors segregated, the Negro League serviced America’s roughly 10 percent black populace. Two verities existed: Black America loved baseball; and “colored” malaise had preceded 1929’s Depression curve. The white-run Eastern Colored League had gone under the financial waves in 1928, a hint of things ahead. In 1931 the Negro National League (NNL) collapsed.36 By 1933, Gus Greenlee, a black numbers shark involved in boxing, night clubbing, and gambling, “moved to revive the defunct Negro National League, this time with six clubs, all of them under the control of his fellow racketeers,”37 including Newark, wrote Geoffrey C. Ward in his 1994 Baseball: An Illustrated History, based upon Ken Burns’ PBS documentary. Before long, he wrote, the “numbers kings” owned most Negro League teams — “among the few members of the [black] community with enough money in the midst of the Great Depression to pay the bills.”38

Ed [actually, James] “Soldier Boy” Semler, said Baseball magazine, was said to run the New York Black Yankees. In Harlem, Alex Pompez, gangster Dutch Schultz’s muscle man, controlled the New York Cubans. Ed Bolden backed the Philadelphia Stars and Tom Wilson financed the Baltimore Elite Giants. If Abe Manley’s gambling money kept the Eagles from going bankrupt, wrote Ward, his remarkable wife, Effa, kept them going each game, knowing the game as well as their manager, to “sometimes signal … her players to bunt or steal by crossing and uncrossing her legs.”39 The second Negro National (Eastern) League lasted for 16 years. All told, according to John Holway’s The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History, 18 franchises competed at one time or another from 1933 to 1948.40 In 1942-48, its champion played each Negro American (Western) League (NAL) leader in a Negro World Series. Prior to 1942, “titlist” meant winning the pennant; thereafter, the Series.

For a long time, redolent of their then-black second-class status, 1926-50 Negro League records were understandably incomplete. Across society, black and white, the Depression made people unconcerned with anything but a job. On his last day in office, President Herbert Hoover said, “We are at the end of our string. There is nothing more we can do.”41 Inaugurated on March 4, 1933, successor Franklin Roosevelt refused to accept defeat, asking and soon getting from Congress an array of powers to combat despair. All decade FDR fought unemployment, business monopoly, and wind and drought turning farms into sand.42 The Negro Leagues would almost surely have not survived the 1930s without him. As things were, they suffered financially, much like Organized Baseball itself.

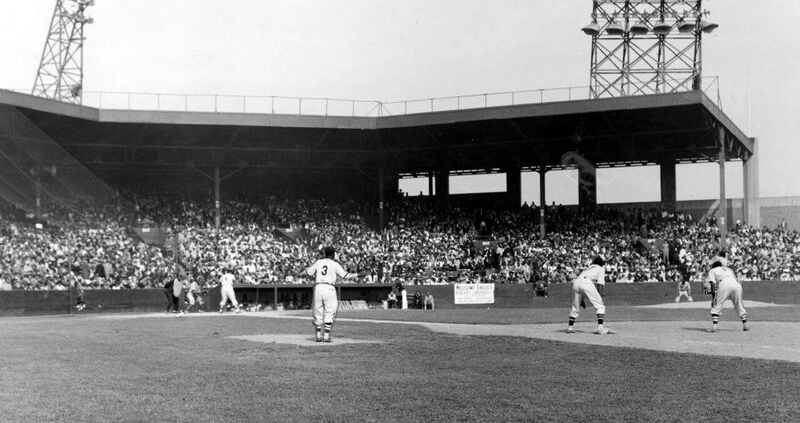

In the September 25, 1965, issue of The Sporting News, Bob Addie quotes Cleveland President Gabe Paul musing how then-Newark Stadium was built “without ticket windows. They had to use portable ticket booths when the park was opened.”43 Each pole stood 305 feet from the plate. Center field loomed 410 feet away. The left-center-field bleachers were far closer to the plate than right or center field, sans seats but “provid[ing] space for a larger crowd” by “roping off the area.” In 1932 lights were added, the park used as a high-school field, leased for special events, and staging stock-car racing, midget racing, and boxing. The air evinced a next-door garbage dump, redolent of Brooklyn’s nineteenth-century Washington Park III, near Gowanus Canal.44 Play was often delayed by odor wafting from trash.45 A deck wrapped the plate from pole to pole. A roof covered the top 70 percent of the seats from nearly third base to first. A General Electric Archives photo46 shows players around the batting cage, the plate a stone’s throw from the backstop. The joint was plain, and the fans were plainspoken.

As The Negro Leagues in New Jersey relates, on one hand “the many ballparks and playing fields” in the state made “fans … witnesses to a high caliber of baseball. [On the other,] (t)he Negro League teams had no ballparks of their own and had to settle for any arena that was available to them.”47 Ruppert was an exception — also, three other Negro League parks, extending this communal feel. In 1926, the Eastern Colored League Newark Stars attended Newark Schools Stadium. Builders evidently ran out of real estate, each line so abbreviated that a drive over the fence counted as a double. In 1933, the revived NNL arose. Its 1934-35 Newark Dodgers filled Meadowbrook Oval at South Orange Avenue and 12th Street — the outfield fence 12 feet high; center field 380 feet from the plate; each pole 300 away; its effect, baseball lighting Depression gloom. Each “Sunday [was] devoted to attending church and baseball games,” read The Negro Leagues.48 At morning service, ministers bade all “an enjoyable time” at the park, their flock then trekking there, “the men sporting their Sunday best. The women wore flowery dresses and hats placed over fancy hairdos.” Everyone was “dress[ed] to the nines.”49

Visiting teams stayed and home players boarded and met supporters at the Grand Hotel at West Market and Wickliffe Street. (The Bears lived at the Riviera Hotel on High Street.50) According to writers Alfred M. and Alfred T. Martin, it “was a haven for African Americans, especially during the days of segregation,” jazz, dance, and other genres rocking to headliners Fletcher Anderson, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton, and Fats Waller — baseball with a beat.51 Since no team owned a park, clubs needed the accessible and suitable. In 1936 the Brooklyn Eagles merged with the Newark Dodgers and began to share Ruppert with the Bears. Inexplicably, the Bears and Eagles never played despite sharing the same house through 1948, “players of both teams … willing.”52 As it was, Newark got an NNL home-field edge: sure facilities, sane scheduling, and steady cash. Admission cost 85 cents for a box, 65 cents a grandstand, 40 cents a bleacher seat. The Bears got 20 percent of the Eagles game’s receipts.53 Each team could plan but the Eagles gained a vital edge in a league whose Job One was finding a place to play.

Bears owner Ruppert died of phlebitis on January 13, 1939, his parent club aptly taking the World Series in each of the Eagles’ first three years — 1936, ’37, ’38. Babe Ruth, whom Ruppert called Root in his German-inflected voice, addressing Babe by his last name, as he did everyone, even close friends, was among the last to see him alive. Before the Bears expired in 1950, the Yankees added Series titles in 1939, ’41, ’43, ’47, and ’49, dedicating a plaque in 1940 in Ruppert’s memory to hang on the center-field wall at Yankee Stadium — “Jacob Ruppert: Gentleman, American, sportsman, through whose vision and courage this imposing edifice, destined to become the home of champions, was erected and dedicated to the American game of baseball.” It rests in Monument Park at new Yankee Stadium.54 Another plaque honors him at the Hall of Fame; Ruppert was inducted in 2013 by its new Pre-Integration Committee, which every three years evaluates managers, umpires, executives, and players of baseball prior to 1947.55

Before Ruppert’s purchase, the unaligned Bears flunked the first division half of their first six years. There were exceptions: Lew Fonseca, baseball’s future film director, once batted .381. Another year, Wally Pipp, his 1925 headache launching Lou Gehrig’s games-played streak, averaged .312. Walter Johnson and Tris Speaker each managed, no longer able to regularly pitch or bat. Soon Ruppert’s farm system, operated by general manager Ed Barrow and successor George Weiss, ran talent like the Passaic River through Newark. By 1932, New York’s first year, the 109-59 Bears placed first, drew a Newark high 342,001, and had six regulars top .300, including comers Red Rolfe and Dixie Walker. The next year’s 102-62ers led the league. At one end, future stars Johnny Murphy and Spud Chandler ended a collective 10-10; the other, Jim Weaver, a once and future big-league starter, 25-11. Bombers on the way down and up intersected. In 1934 Murderer’s Row ex-pitcher and new hurler Bob Shawkey waved another flag. Twinkletoes Selkirk hit .357 for Newark, then .313 in the Bronx, but couldn’t replace the Babe, as advertised. In 1936: Ossie Vitt succeeded Shawkey. In 1938, 1941, 1942, the Bears won the pennant, even as recession troubled FDR’s second (1937-41) and early third term. None surpassed New Jersey’s largest city’s Greatest-Ever Team.

To Jerry Izenberg, “Joe Basile’s 25-piece band was the centerpiece of the Bears’ opening days just as Lena Horne, Joe Louis, and … Effa Manley … were the focal point of the Eagles’ openers.”56 Save score, Basile had little to enjoy Opening Day 1937. “In a dull, dump and discouraging setting at Ruppert Stadium,” wrote the New York Times, the Bears beat Montreal, 8-6. “The sun never showed up and neither did the anticipated crowd of 20,000. Only 5,000 showed,”57 more returning. The 1937 Newark Bears won the pennant by 25½ games, finished 109-43, and savored Joe Beggs (21-4), Atley Donald (19-2), Vito Tamulis (18-6), and Steve Sundra (15-4). Newark hit 140 homers and batted .300. Charlie Keller, later a.k.a. “King Kong,” debuted at .353, Babe Dahlgren batted .340, Buddy Rosar .332, George McQuinn .330, Willard Hershberger .325, and Frankie Kelleher .306. Bob Seeds, nicknamed Suitcase for his five big-league teams, added .305 with 20 homers, in one weekend going deep 10 times in 17 at-bats with 17 RBIs.58 Joe Gordon, 22, hit .280 in his last minor-league year. Tommy Henrich, 24, played in seven games before joining the Yanks to stay. An italicized season ended with an exclamation point: Newark swept Syracuse and Baltimore in the IL playoff and Governor’s Cup final, respectively, then erased a 0-3 deficit to nip Columbus in the Junior World Series.

Like the Eagles, the Bears — columnist Bill Newman recalled the “The Wonder Bears”59 — knit Newark. In “Old Newark Memories,” he evoked their eight-game five-cent “Knothole Ticket” for grade-school children — how after each game hundreds waited at the players exit. One day Newman gave his hero, pitcher Tamulis, a scorecard and pencil and asked for his autograph. Vito signed, held on to it, looked down at Newman, and said, “Hey kid, I bet I know something you don’t.” Bill: “What?” Tamulis: “You’re standing on my foot.” Heroes were closer then, dialogue more personal. On “Father & Son Night,” some kids got in free with a father who bought a ticket, Dads finding they had never met.60 In 1938 new skipper Johnny Neun evoked a favorite uncle, leading the Bears to a 104-48 first-place, postseason defeat of Rochester and Buffalo, then loss to Kansas City in the Junior World Series. Marius Russo joined the Bombers after going 17-8. A World War I tune asked, “How you gonna keep ’em down on the farm?” Newark couldn’t. Keller left after stroking .365 to stay at The Stadium a decade. Tommy Holmes batted .339 and couldn’t find a position. Dealt, he became a two-time NL hits titlist. How fertile was the Yanks’ farm? Hank Borowy, 9-7 at Newark in 1939, didn’t reach the bigs until going 15-4 in 1942.

By then, manager Neun owned another title from 1940, beating Jersey City, Baltimore, and Louisville in the postseason. In 1941’s last summer of an uncertain peace, the 100-54 Bears beat Rochester in the playoff but lost a seven-game Governor’s Cup final to Montreal. Their last wisp at the top aired versatility. That year, Newark’s Johnny Lindell had a 23-4 W-L record and 2.05 ERA and batted .298. By 1943-44, he twice topped the AL in triples. Tommy Byrne was a 1940-42 Bears starter who once finished 17-4 and hit .328. A decade later he buoyed the Yanks staff —16-5 one year — and pinch-hit, too. In 1932 GM Barrow had hired Weiss as farm director. The system that Weiss built from four teams to 20 by 1947 survived Newark’s IL demise. A decade-later film headlined Winning with the Yankees.61 “What makes the Yankees tick?” narrator Mel Allen begins. Personae fuse: Billy Martin steals home. Skipper Casey Stengel tutors rookies and coaches Frank Crosetti, Bill Dickey, and Ralph Houk. “The scout’s a nice guy, and tries to put you all at ease,” Allen purrs. The numbers ran with Casey, like the Bears.

In July 1942, wartime US Navy member and famed pitcher Bob Feller fueled a Red Cross and Navy Relief Society benefit for the Norfolk Naval Training Station versus the Quantico Marines in a five-inning game at Ruppert. Babe Ruth, Larry MacPhail, Dolly Stark, and Gil Stratton Jr. umpired. Celebrities Lucille Manners and Gabriel Heatter appeared.62 A Newark-Toronto IL set followed. In 1943 Newark drew only 983 per date. The bigs’ future first relief ace, Joe Page, was 14-5 as a starter. Ghost of Yankees Past George Selkirk became manager. In 1947 Newark thudded to a 65-89 end. Gene Woodling’s .289 was another ’50s Yanks portent. Sherm Lollar hit 16 homers but found no room in the Bombers’ tri-tiered inn: thus, dealt to Chicago, became a seven-time All-Star. Two other prospects, Yogi Berra and Bobby Brown, batted .314 and .341 respectively in 1946. Early in their Yanks tenure the roommates were reading at night — Berra a comic book and the future medical student, Dr. Brown, a journal. Finishing his comic, Yogi said, “So how is yours turning out?”63 Such Bears alumni conjure almost any 1950s official World Series program as the Yanks captured eight pennants in that decade’s 10 years.

In 1948 Newark’s Bob Porterfield threw 20 complete games in 22 starts. He was again heard from when he went 22-10 for the Senators in 1953. The Bears’ last year was 1949, Newark’s 5.50 ERA earning last place on merit. Its last skipper was Buddy Hassett. A better choice might have been comic Buddy Hackett. The franchise’s story had begun with the ’26ers soaring (96-66) and drawing (3,322 a game). It ended with the ’49ers breaking Newark’s worst record (55-98) and peacetime gate (88,170). Most sat home to watch on the new kinetic tube the Dodgers, Giants, and Yankees as the racial line dissolved. In 1945 Jackie Robinson signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, a seismic act that precipitated other players leaving non-big-league black baseball. Historic and inevitable as their exodus was, Effa Manley knew what it foretold. Unable to survive the major leagues’ at last truly national cachet, the Negro Leagues were doomed from the date Jackie inked his pact. Even so, Newark’s greatest moment followed his arrival.

In 1935 the Brooklyn Eagles finished 32-30, the Manleys hoping that the merger with the Newark Dodgers would ensure next year’s NLL’s Eastern Division. Instead, the ’36ers fell to 25-29-1. In 1937 Newark surged to 35-21-2 (second place), The decade closed at resolutely .500 (23-23) in 1938 and .638 percent second-half (37-21-1) in 1939, the latter’s second-placers losing a first postseason to the Baltimore Elite Giants. (Most split-season records are not available.) Newark was 26-22-1 in 1940 and 30-25-1 in 1941, respectively. That December 7, Japan attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, bringing America into World War II. Each Negro League and major-league team lost players via draft and/or enlistment. The Eagles sent a dozen men to the armed forces, including all branches of the military.64 Ultimately, like players from other teams, they served their country in the European and Pacific Theaters and elsewhere. Much later Congress feted all-black divisions for their distinction — belatedly, but finally.

In 1942-44, Newark clung to mediocrity: 36-33-3, 26-32, and 32-35. As war ended and soldiers slowly returned, the 1945 Eagles, many players still at a front, plodded to a 27-25 .519 third-place finish. Few things suggested a championship. Still, advantages remained. Other NLL teams could not afford scouting. Geography was Manley’s scout as many of the Eagles players were locals: Larry Doby from Paterson, New Jersey; Monte Irvin, East Orange; Manning, Pleasantville. The Negro Leagues retraces a vagabond slate: 150 yearly games of spring training, regular season, exhibition, and post; a “grueling schedule” of two-week two-way travel from Newark to “Baltimore, Richmond, Bellefonte, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and Indianapolis,” return adding Altoona, Canton, Akron, and Columbus, including twin-bill and twilight that meant all night in a bus.65 Only the Eagles’ bus was air-conditioned. They returned to a stable homestead, Ruppert Stadium, which no other team possessed.

Home and away, a roster of great players preceded 1946’s likely best-ever African-American club. Among them was the black press’s vaunted “Million Dollar Infield.” At first base — he also played the outfield — Mule Suttles swung a 50-ounce bat to hit a .317 Negro League average for eight teams, including the 1936-40 and 1942-44 Eagles. At second base, Dick Seay starred defensively for Newark from 1937 to 1940, making the double play so quickly that in the argot of a later age the ball seemed radioactive to his glove. He could even bat, using the bunt and hit-and-run to average as high as .267 in 1940.The infield’s shortstop, Willie Wells — “The Devil” —was only demonic to the other side. Wells fortified 10 Negro League teams at least briefly from 1924 to 1948, including Newark in 1936-39 and 1942, batting as high as .363 and .355 for the Eagles. Third baseman Ray Dandridge played for the Newark Dodgers in 1933-34-35 — once batting .432 — and Eagles in 1936 through 1938. He left Newark “to play in Mexico for [several] years because he was offered a good salary,” states The Negro Leagues in New Jersey, “paid all his expenses, and was provide with a family apartment.”66 Returning to Newark, he hit .341 in 1944. The Eagles’ greatest third baseman made Cooperstown in 1987.

From 1920 to ’47, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey was a black baseball icon, playing primarily for five teams. In 1939-41, he became the Eagles’ star catcher. In 1945, rejoining Newark at 47 — his first of three final years — Biz hit .262 part-time. Cooperstown ’06 retired having played in 998 games. Specific to this book, Mackey managed the ’46ers to a world title,67 his staff starring three torrid starters. A 1946-48 Eagle, Rufus Lewis used a medley of pitches to beat Kansas City twice in the 1946 World Series. Later, he thrived in the Mexican League and other winter-ball venues and pitched until injury forced him to leave the game in the early 1950s, by which time a mishap had forced second 1946 starter Max Manning out of baseball, too. Born in Georgia, Max had initially joined the semipro Johnson Stars before signing with Newark. The righty brought a high kick, fastball, glasses, and nickname — “Dr. Cyclops”68 — his first Eagles game earning an A: consecutive strikeouts of Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Sam Bankhead, and Dave Whatley. Even healthy, Lewis and Manning had been bypassed by Mackey for Leon Day, who started on Opening Day 1946. Day had just returned from the war and had not pitched professionally in two years, but made up for lost time with a 2-0 no-hitter against the Philadelphia Stars. From 1934 to 1946, the 1995 inductee at the Hall of Fame played every position but catcher, usually second base or center field, if not forging a .687 pitching percentage. His winning percentage is second-best with Pedro Martinez at Cooperstown, behind only Whitey Ford.69

The glorious 1946 Eagles finished a pennant-winning 56-24-3 (.700 percentage), fueled largely by “The Big Four,” as writers christened them — future Hall of Famers Larry Doby and Monte Irvin, plus Lennie Pearson and Johnny “Cherokee” Davis. Outfielder Davis was a 1940-48 Eagle, topping .300 yearly from 1942-46, as high as .343 and .341, and batting a lifetime .301. A 1937-48 Eagle, Pearson made five East-West All-Star Games, five times passed .300, peaked at .342 in 1940 and 1942, smacked 11 homers in 1942, and averaged .393 in the 1946 Series. Earlier integration would have made Lennie a big-league star. Instead, after Newark’s baseball finis, Pearson became player-manager of the 1949 champion Baltimore Elite Giants and concluded with the 1950-51 Triple-A American Association Milwaukee Brewers.70

At the time and since, the Eagles’ greatest victory was the 1946 World Series — by consensus the Negro Leagues’ last moment in the sun. None helped like their two most noted players, each an adopted Jersey son. Larry Doby was born in 1923 in Camden, South Carolina,71 a four-sport athlete in Paterson, New Jersey. Turning 17, he signed a 1942 contract for $300 with Newark stating that he would play till September before starting college. On October 23, 1945, Doby, only 21, heard on Armed Forces Radio of Brooklyn GM Branch Rickey signing Jackie Robinson to a contract with its Montreal Triple-A affiliate. Till now he had planned to coach or teach. Suddenly, Larry felt that he might crack the bigs, too.72 Doby returned from war to play for the San Juan Senators in Puerto Rico, then rejoined Newark in 1946.73 He made the All-Star roster, hit .329, had 52 RBIs, stole 8 bases, and led the team with 281 plate appearances, 62 runs, 80 hits, 8 homers, 8 triples, 14 doubles, and 37 walks — almost everything there was to lead. Among those watching was Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck. In late 1944 Kenesaw Mountain Landis, baseball’s first commissioner and a segregationist, had died; successor A.B. “Happy” Chandler opened the big-league door. Veeck now plucked Larry from Newark to desegregate the American League. Doby debuted in Cleveland on July 5, 1947.

Like Doby, the Eagles’ other Hall of Famer ’73 left rural South Haleburg, Mississippi, for urban North Orange, New Jersey. After trying college, Monte began with Newark in 1938-39. Hitting .371 and .395 in 1940-41, Irvin asked for a raise. Refused, he won the 1942 Triple Crown at Veracruz in the Mexican League74 — and was assigned by the US Army to its Corps of Engineers in Europe, historically in 1944-45’s Battle of the Bulge. Back home, Irvin, solicited by Rickey, stayed in Newark. Prizing her players, Effa Manley had let Robinson and [pitcher] Don Newcombe leave her team [in 1945] without Rickey paying a cent. She wasn’t about to forfeit rights to Irvin. “… Mrs. Manley felt that Branch Rickey was obligated to compensate her for my contract,” Monte said. She “told Rickey that … she wasn’t going to let him take me without compensation.” If Rickey tried, Effa vowed to sue, whereupon Branch’s interest ebbed. Monte’s 1946 was as spectacular as the team’s, hitting .374 and slugging .564.

In 1949, the four-time NNL All-Star signed with the Giants, ravaging the IL with Triple-A Jersey City. He spent most of 1950 with the parent ’Jints, then joined them for good next year, his sole dilemma time. In 1951, he was 32. Irvin had spent a decade fighting segregation and war — yet hit .312 as the Giants erased a 13½-game Brooklyn lead. Monte retired in 1957 after batting .293 in just 764 major-league matches. In 2006, Orange Park in Orange was renamed Monte Irvin Park. The pioneer died at 96, in 2016, the year his life-sized bronze statue was dedicated, 13 miles from Ruppert Stadium. Still alive at the end of 2018 was a man who pitched briefly there but later reigned at Ebbets Field. On May 20, 1949, Don Newcombe debuted for Brooklyn, that year among the first four black players named to a big-league All-Star team, with Cleveland’s Doby and Dodgers teammates Roy Campanella and Jackie Robinson.

Born in Madison, raised in Elizabeth, Newcombe played integrated school and sandlot ball before joining the Eagles at 18: his two-year mark, 8-6. Newcombe and Baltimore’s Campy then joined America’s first racially integrated pro baseball team, the 1946 New England League’s Nashua Dodgers. Don became the first pitcher to be Rookie of the Year, Most Valuable Player, and Cy Young Award honoree — in 1949, the first black pitcher to start a Series game.75 In 1951, Newk was the first black to win 20 games in a year — and 1956, first of any race or either league as same-year Cy Younger and MVP.76 He had a career .271 batting average and belted 15 homers. In 1956 a rival punctured his best (27-7) year, Yogi Berra making Don his piñata in the Series, slamming a Game Two grand slam and two seventh-game belts. Viewing on TV, President Eisenhower later wrote him: “I think I know how much you wanted to win a World Series game [he never did]. I for one was pulling for you,” but “hard luck is something that no one in the world can explain.” Ike suggested that “you think of the twenty-seven games you won that were so important in bringing Brooklyn into the World Series.”77

In 1946, a Newark poster-turned-collector’s-item read, “1945 [sic, 1946] Negro League World Series: Kansas City Monarchs Featuring Buck O’Neil, Satchel Paige, and Ted Strong vs. The Newark Eagles, Featuring Leon Day, Larry Doby, and Monte Irvin!”78 The fifth 1942-48 postseason joust between the Negro Leagues’ National and American League titlists became the most surpassing. In the Series opener at the Polo Grounds, Paige yielded one run and scored the Monarchs’ 2-1 decider. Two days later, ex-heavyweight boxing titlist Joe Louis threw out the first pitch at Ruppert Stadium. Doby homering, the Eagles tied the Series, 7-4. In Game Three, Newark pitching dissolved in a 15-5, 21-hit KC rout. Next night Irvin’s four hits and Rufus Lewis’s complete game squared things, 8-1. Game Five shifted to Chicago’s Comiskey Park, the Monarchs taking the Classic lead a third time, 5-1. The sixth set could have been staged at Fenway Park or Ebbets Field — drives clearing or careening around Ruppert Stadium. Irvin homered twice and Pearson once: Newark, 9-7. The September 29 final lured 19,000 to Ruppert. They saw Leon Day make a sprawling eighth-inning catch to save the Series with his glove; then, in the home half of the inning, Doby and Irvin walk and Johnny Davis lash a two-run double to give Newark a 3-2 victory.

The triumph was short-lived. After Rickey signed Robinson, the road ahead was clear, like a plunge in NNL attendance. Even at Ruppert Stadium, “The question of the day [became], ‘How did Jackie do today?’” The 1947 Eagles finished 53-41-1 (.564) to finish second — yet drew just 57,000. Their final year, a 33-1-3 1948, barely made a scratch. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, Manley urged a firm relationship between the majors and the Negro Leagues. By contrast, the bigs wanted the extinction of the Negro Leagues: Less competition meant more profit. The 1948 season left the Manleys with a $25,000 deficit. They sold their interest in the Eagles for $15,000, including all assets, player contracts, and the team bus. The couple received $5,000 for Irvin’s sale to the Giants. The NNL contracted and merged into the NAL, were sold, moved to Texas, and became the short-lived Houston Eagles.79

That November, Parke Carroll, Bears general manager, confirmed that the city’s other trust, the Newark Baseball Club of the International League, “is for sale,” noting that it had led the league in 1948 road attendance but ranked second-to-last at home.80 The Bears blamed “inadequate transportation to and from Ruppert Stadium” and “a smoke nuisance” — in today’s cant, pollution — for waning crowds. In truth, television and integration — the former, voluntary; the latter, necessary — destroyed the Bears and Eagles, respectively. In 1948, Ruppert staged another sport that TV overexposure would kill — boxing — hosting the Rocky Graziano-Tony Zale middleweight title bout.81 Once a fight hotbed, Newark’s revival didn’t take. In 1950, its IL franchise moved to Pynchon Park in Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1959 Ruppert Stadium hosted a final year of the Newark Indians and the NAL.

On October 16, 1952, the Yankees gave up the ghost that baseball would return there, announcing, “The park will be torn down and the property offered for sale for real estate.”82 That November 25, the Newark Board of Education intervened, buying Ruppert Stadium for $275,000 and urging that another $50,000 be spent to make it a school sports center. In 1961 a 9-acre part of the 20-acre site was sold for $180,000 to developers of industrial property.83 The stadium was leveled in 1967 and the land sold a year later. Where Ruppert stood is now “a landscape of chain-link fences and warehouses, factories and trucks.”84 Far more was demolished than earth and stone.

By 1981, Effa Manley’s cancer of the colon regressed into peritonitis. She had a heart attack on April 16, at 84, four days after the death of her idol, Joe Louis.85 Effa was buried in Holy Cross Cemetery at Culver City in Los Angeles, her tombstone reading, “She loved baseball.” Newark loved it in 1999, debuting a $34 million taxpayer-financed 6,200-seat Riverfront Stadium. In baseball’s once non-big-league capital, the new Bears of the independent Atlantic League hoped to recall a nonpareil baseball age. On May 8, 2001, hoping to draw on 5.4 million people within a 15-mile radius,86 the ballpark was renamed “Bears and Eagles Riverfront Stadium.” Two Newark alumni and Hall of Famers stood side-by-side at a ceremony to recall Newark’s greatest teams of the Negro and International Leagues and “designed to right a historical wrong” — how, due to segregation, their two teams and leagues never met.87

Yogi Berra of the 1946 Bears evoked Newark drawing “great here. When we’d play the Jersey City Giants, we packed the place.” Larry Doby of the 1940s Eagles recalled not thinking of “making 300, 400 dollars a month to play baseball [as] … work. We just loved to play.” Even now, they wished they could have played each other. Sadly, the park once seen as the cornerstone of Newark’s urban renewal failed to turn the corner. In 2008 the Bears folded, joined the Canadian American Association in 2011, and two years later died. In 2014 a liquidation auction was held. One headline read: “Game Over: Newark Bears Officially Out of Business, as Baseball Fades From City Again.”88 For the moment, F. Scott Fitzgerald sadly had been correct: “There are no second acts in American lives.”89

Sources

My appreciation to the distinguished Negro Leagues historian and author Larry Lester, whose advice has been invaluable referencing events and players. I also want to thank longtime friend and colleague Ken Samelson for his great help. Unless otherwise indicated, individual, team, and league Negro League batting, fielding, and pitching statistics are courtesy of the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database from seamheads.com/NegroLgs/ powered by the Baseball Gauge. In addition to sources cited in the Notes, most especially the Society for American Baseball Research, the author also derived major- and minor-league baseball statistics from baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org and relevant websites for box scores, player, season, and team pages, batting and pitching logs, and other material relevant to this history. FanGraphs.com provided statistical information. In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Books

Benson, Michael. Ballparks of North America: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia of Baseball Grounds, Yards and Stadiums, 1845 to 1988 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1989).

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball In New York City: An Illustrated History, 1885-1959 (Jefferson City, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017).

Shannon, Bill, and George Kalinsky. The Ballparks (New York: Hawthorn, 1975).

Smith, Ron. The Ballpark Book: A Journey Through the Fields of Baseball Magic (St. Louis: The Sporting News Co., 2000).

Newspapers

The New York Times has been a primary source of information about Ruppert Stadium. Another key source has been the Newark Star-Ledger. Other sources include the Associated Press, The Sporting News, Washington Post, and USA Today.

Interviews

Larry Lester, with author, November 2018.

Harold Rosenthal, with author, March 1982.

Notes

1 enotes.com/Shakespeare-quotes/whats-past-prologue.

2 digitalballparks.com/International/Ruppert_640_2.html.

3 “Ruppert Stadium to Be Torn Down: Newark Property of Yankees Will Go for Real Estate,” New York Times, October 17, 1952: 37.

4 revolvy.com/page/Newark-Bears-(International-League).

5 newarksports.net/buildings/ruppert.php. “Newark Sports Old Newark”

6 milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=53.

7 “Ruppert Stadium to Be Torn Down.”

8 “Ruppert Stadium Is New Name of Baseball Park in Newark,” New York Times, January 9, 1932: 23.

9 “Ruppert Stadium to Be Torn Down.”

10 Ibid.

11 baseballhall.org. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

12 Ibid.

13 Alfred M. Martin and Alfred T. Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey: A History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 67.

14 milb.com/milb/history/top111.jsp “Top 100 Teams.” MilB.com. 2001.

15 baseballreflections.com/2018/03/18/look-casey-stengel/.

16 Jay Maeder, “Jacob Ruppert: The Old Ball Game,” New York Daily News, March 2, 1999: 2.

17 Jay Brooks, “Historic Beer Birthday: Jacob Ruppert, Jr.,“ August 5, 2018. brookstonbeerbulletin.com/tag/baseball

18 Pat Gannon, “Col. Ruppert’s Typical ‘Burgher’: Won Battle with Ban Johnson,” Milwaukee Journal, January 15, 1939: 12.

19 “From Tweet to Crocker: Do the Changes in Men and Methods Show That Parties in Great Municipalities are Growing Better or Worse?” Deseret News (Salt Lake City), January 6, 1906: 24.

20 “New York City — Bryan Carries It by About 28,000 — Belmont Elected; Ruppert Wins; McClellan and Cummings Re-elected,” New York Times, November 7, 1900: 1.

21 “Democrats for Congress — Belmont Turned Down for Sullivan and Hearst. Goldfogle, Sulzer, McClellan, Rider, Shober, and Ruppert Named in Other Districts — Several Conventions Adjourned,” New York Times, October 3, 1902.

22 “Col. Ruppert Buys Haffen Brewery: Sale Involving $700,000 Is One of the Largest Made in the Bronx; To Discontinue Business; Land on Which Brewery Stands Will Be Used as a Site for Modern Office Buildings,” New York Times, January 20, 1914.

23 Maeder, “Jacob Ruppert.”

24 brainyquote.com/quotes/ring_lardner_137685.

25 Daniel R.Levitt, “Jacob Ruppert,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/b96b262d.

26 “Miller Huggins to Pilot Yankees: Signed for Two Years to Succeed Wild Bill Donovan. Tom Connery Will Scout for Yankees,” Hartford Courant, October 26, 1917: 14.

27 “Col. Ruppert buys out Col. Huston for $1.5 Million,” Yankees Timeline. Major League Baseball: May 21, 1922. newyork.yankees.mlb.com/nyy/history/timeline.jsp.

28 Richard Hoffer, “Our Favorite Athletes. It’s Not Nice to Play Favorites But We’re Making An Exception Here Celebrating Not Necessarily the Greatest but Those Who Brought Us the Greatest Joy,” Sports Illustrated, July 12, 1999.

29 baseball-injury-report.com/new-york-yankees/.

30 Harvey Frommer, “Colonel Jacob Ruppert: The Man Who Build the Yankee Empire (Part II), August 8, 2013. theepochtimes.com/colonel-jacob-ruppert-the-man-who-built-the-yankee-empire-part-ii_237122.html.

31 newyork.yankees.mlb.com/nyy/ballpark/stadium_history.jsp.

32 Dick Heller, “Going by the Numbers,” Washington Times, January 19, 2009.

33 Daniel R. Levitt, “Jacob Ruppert,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/b96b262d.

34 Martin and Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey, 20.

35 Jerry Izenberg. “Berra, Doby Hoping New Name Is a Sign an Old Rift Is Healed,” Star Ledger (Newark), May 9, 2001.

36 Geoffrey C. Ward, Baseball: An Illustrated History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 198.

37 Ward, 203.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 John B. Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001).

41 brainly.com/questions/9370338.

42 Samuel I. Rosenman, Working with Roosevelt (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972), 92-96.

43 Bob Addie, “ADDIE’S ATOMS: The Stadium They Built Without Ticket Windows,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1965.

44 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of All 271 Major League and Negro League Ballparks Past and Present (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1992), 118.

45 Lowry, 288.

46 Schenectady (New York) Science Museum.

47 Martin and Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey, 17.

48 Martin and Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey, 10.

49 Ibid.

50 Izenberg. “Berra, Doby Hoping New Name Is a Sign an Old Rift Is Healed.”

51 Martin and Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey, 71.

52 Martin and Martin, 20.

53 Ibid.

54 Richard Sandomir, “Everyone Agrees Steinbrenner’s Plaque Is Big,” New York Times, September 21, 2010.

55 Dave Anderson, “No Longer Overlooked,” New York Times, December 8, 2012.

56 Izenberg, “Berra, Doby Hoping New Name Is a Sign an Old Rift Is Healed.”

57 Louis Effrat, “Newark Celebrates Inaugural With 8-5 Victory Over Royals,” New York Times, April 23, 1937: 26.

58 Russell Roberts, Discover the Hidden New Jersey (Rutgers, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 75.

59 Bill Newman, “Old Newark Memories.” oldnewark.com/memories/sports/newmanbears,htm.

60 Ibid.

61 Winning with the Yankees, Mel Allen narrator (Frankenmuth, Michigan: Encore Entertainment, Inc., 1956).

62 “Celebrities Listed for Newark Program,” New York Times, July 24, 1942: 14.

63 jworld.com/news/2015/oct/10/your-turn-berra-was-one-kind/.

64 Martin and Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey, 76.

65 Martin and Martin, 78.

66 Martin and Martin, 95.

67 Martin and Martin, 50.

68 Martin and Martin, 53.

69 baseballhall.org. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

70 Martin and Martin, 62.

71 sabr.org/bioproj/person/4e985e86.

72 Martin and Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey, 31.

73 John McMurray, “Larry Doby.” sabr.org/bioproj/person/4e985e86.

74 Richard Justice and Chris Haft, “Trailblazer Irwin Dies at 96,” MLB.com, January 12, 2016.

75 David Nemec and Scott Flatow, Great Baseball Feats, Facts, and Firsts, 2008 Edition (New York: Signet, 2008), 198.

76 Nemec and Flatow, 152.

77 “Eisenhower Advises Newcombe To Remember His 27 Triumphs; In Letter, President Says He Was Pulling for Don, Routed Twice in World Series,” New York Times, November 10, 1956: 233.

78 newarksportsnnet/photos/displayimage.php?pid=33. Poster from Rich Olohan.

79 Martin and Martin, 72.

80 “Bears Up For Sale, Yankees Confirm,” New York Times, November 12, 1948: 37.

81 “Jersey Tries Comeback as Fight Center, Washington Post, June 8, 1948: 19.

82 “Ruppert Stadium to Be Torn Down.”

83 “Newark Plot Sold for Industrial Plant,” New York Times, August 25, 1961: 37.

84 Kevin Coyne.

85 peoplesworld.org/article/today-in-women-s-history-birth-of-effa-manley-baseball-hall-hall-of-famer/.

86 Ronald Smothers, “Newark Hails Baseball’s Return, but the High Cost of a New Stadium Raises Doubts,” New York Times, July 4, 1999: 21.

87 Associated Press, “Newark Rights Baseball Wrong,” The Record, (Hackensack, New Jersey), May 9, 2001.

88 Mark Di Ionno, “Game Over: Newark Bears Officially Out of Business as Baseball Fades From City Again,” Newark Star-Ledger, April 28, 2014.