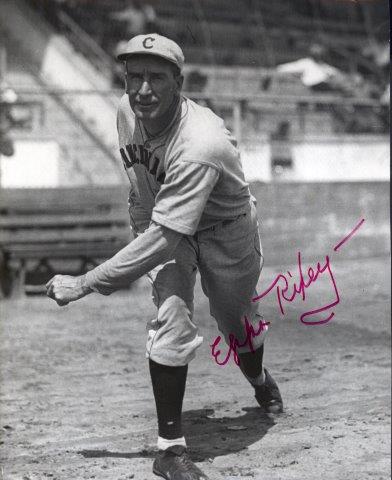

Eppa Rixey

Without his unforgettable name, Eppa Rixey might be one of the more forgotten members of the Hall of Fame. His 266-251 won-lost record doesn’t stand out, yet his win total stood as the National League record for left-handers until Warren Spahn surpassed it in 1959. Rixey greeted the moment with characteristic humor, saying he was glad Spahn had broken his record because it reminded everybody that he had set it. Conversely, his 251 losses are the most ever for a southpaw and ninth-most for all pitchers.

A tough competitor on the field but a gentleman and good teammate off it, Rixey was an anomaly. Whereas the average ballplayer of the era came from a farming, labor, and often immigrant background, Rixey’s background was comparatively aristocratic. The Rixeys of Culpeper were Virginia gentility, descended from the Riccias of Italy, who had come to America by way of England, Scotland, and France. Eppa Rixey Sr., a banker, married the former Willie Alice Walton. Eppa Jr. was born May 3, 1891, the fourth of six children. Eppa attended school in Culpeper until he was 10, when the family moved to Charlottesville. Completing high school in Charlottesville, he entered the University of Virginia, graduating in 1912 with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry.

The mainstay of Virginia’s pitching staff, he also lettered in basketball, using his 6-foot-5 height and 210 pounds to advantage. He jumped directly from the university to the Philadelphia Phillies upon graduation but returned to Charlottesville in offseasons to earn two masters degrees (chemistry and Latin) with side trips into mathematics. During the winter he taught Latin at Episcopal High School in Washington, D.C. Rixey’s background and education were enough to set him apart from the average ballplayer, but he went a step further, writing poetry in his spare time, particularly enjoying sonnets and triolets. Although ballplayers resented college men, he gained their respect by holding his ground when they initiated him.

Rixey jumped from the Virginia pitching staff to the Phillies through the efforts of National League umpire Charles (Cy) Rigler, who was moonlighting on the basketball and baseball staffs of the university. Rigler suggested the move to Rixey, who initially refused, saying he planned to be a chemist. Rigler sweetened the deal by promising to split equally with the young pitcher whatever finder’s bonus he might receive from Philadelphia, which turned out to be $2,000. Rixey agreed because the United States was suffering an economic downturn in 1912, his father’s bank was taking some losses, and he wanted to help his younger brother William (who became a physician) stay at Virginia. However, the league passed a rule prohibiting umpires from scouting for any individual team, and neither Rigler nor Rixey ever saw a dime. Nevertheless, Rixey joined Philadelphia in 1912 after graduating from Virginia.1

Eppa Rixey’s career is a tale of two pitchers. As a Phillie, Rixie was inconsistent. His first two seasons were respectable (10-10 and 9-5), even promising given his youth, but his third (2-11, 4.37) was a disaster. His fourth season, with the Phillies winning their first pennant, was better in terms of ERA, but he was just 11-12 in wins and losses. A key to Rixey’s improvement was new manager Pat Moran‘s confidence in him. Moran brought him into the third inning of the deciding fifth game of the World Series with Boston in relief of Erskine Mayer. Rixey was stung by home runs by Duffy Lewis and Harry Hooper, the latter bouncing into the center-field bleachers constituting what would be a ground-rule double under today’s rules. He wound up taking the loss. In 1916 the Phillies improved their won-lost record but came in second to Brooklyn. Rixey, though, had perhaps his best season ever, going 22-10 with a microscopic 1.85 ERA and a career-high 134 strikeouts. He fell off in 1917, leading the league in losses with 21, but he had a good ERA (2.27) and threw four shutouts.

Rixey lost the 1918 season to the war, serving with the Chemical Warfare Division in Europe. His return from the military, marked by rustiness and dissatisfaction with Phillie managers Jack Coombs and Gavy Cravath, led to two abysmal seasons (6-12 and 11-22) with last-place teams. On February 22, 1921, he was happy to be traded to Cincinnati in exchange for Jimmy Ring and Greasy Neale. He was back playing for Pat Moran.

Rixey and Cincinnati were meant for each other, and he would pitch there for 13 seasons, finishing up in 1933 at the age of 42. He blossomed into an outstanding pitcher, winning a hundred games in his first five seasons and winning consistently for eight years. Even in his final campaign he still had enough, pitching mostly against Pittsburgh, to post a 6-3 record with a 3.15 ERA. He set a record in 1921 not likely to be equaled, serving up only one home run in 301 innings. He led the league in wins in 1922 with 25 and between July 24 and August 28, 1932, threw 27 consecutive scoreless innings.

Everything—except the nickname “Jeptha” that sportswriter William Phelon hung on him, which he tolerated but didn’t like—was falling into place for Rixey. He became something of a bon vivant unable to take Prohibition seriously. From May 9 to May 18, 1922, a detective known only as “Operative No. 40” tailed Rixey all over Cincinnati. He noted that Rixey was sometimes alone but usually in the company of several different men and women, whom he described in detail. Some of the people were known, like teammates Rube Bressler and Greasy Neale, others not. Whatever circuitous route they took, they always wound up at the Foss-Schneider Brewing Company. After 10 days of observation of Rixey (“Subject”) and his friends, Operative No. 40 came to a remarkable conclusion: “So I think if Subject is drinking, he is getting it at the brewery.” Who engaged “Operative No. 40” is a mystery (presumably the Reds or the family of a prospective lady friend), but the bigger mystery is that anyone was surprised, shocked, or interested.2

Rixey settled down and on October 29, 1924, married Dorothy Meyers in St. Thomas Church in Terrace Park, a suburb of Cincinnati. They had two children, Eppa III and Ann. The Rixeys lived in the Cincinnati area, where Eppa worked during the winter in the insurance agency his father-in-law, Charles Meyers, had founded in 1888. Grandson Eppa Rixey IV was the chief operating officer of the Eppa Rixey Insurance Agency, whose motto was “Hall of Fame Performance for Your Insurance Needs” until 2003, when the company was acquired by Mark E. Berry and merged into the Berry Insurance Group.

To cap off his happy and prosperous life, the Veterans Committee elected Eppa to the Hall of Fame on January 27, 1963. He was the first Virginian to be so honored. Unfortunately, he was also the first honoree to die between election and induction, suffering a fatal heart attack on February 28. (Coincidentally, the second was fellow Virginian Leon Day in 1995.) Rixey is buried in Greenlawn Cemetery in Milford, Ohio.

Despite his size, Rixey was a finesse pitcher, working deep into the count to set up a hitter, never giving in, striking out few and walking even fewer, making the hitter hit the ball. A smart pitcher, he thought most hitters were dumb. Rube Bressler told Lawrence Ritter in The Glory of their Times that Rixey remarked upon his astonishment that on the 2-0 or 3-1 count almost every hitter in the league looked for his fast ball and never got it!3 He was durable, frequently working 280 or more innings. While surrendering more than a hit per inning, he didn’t hurt himself with walks or home runs or errors; he fielded his position well, handling 108 chances without an error in 1917. And, like all good pitchers on generally weak teams, he suffered more than his share of losses. Similar southpaw contemporaries include Slim Sallee and Herb Pennock. Tom Glavine, although he walked and struck out more hitters more than did Rixey, pitched with the same mindset.

Rixey was the consummate Virginia gentleman, a fellow who took everything but losing (he could punish locker rooms or disappear for a day or two) and those who taunted his Southern heritage and thick drawl with renditions of classics like “Marching through Georgia” with gentle wit and self-deprecating humor. Visiting Cooperstown after he retired, he sent family and friends a post card with this message: “I finally made it!” Hearing he’d been elected to the Hall of Fame, he joked, “I guess they are really scraping the bottom of the barrel, aren’t they?”4

A top-flight pitcher for many years, Eppa Rixey graced his team and enriched his community.

An updated version of this biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin. It originally appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Fleitz, David L. Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland, 2004).

Hoie, Bob, Carlos Bauer, et al, eds. The Historical Register: The Complete Major & Minor League Record of Baseball’s Greatest Players (San Diego and San Marino: Baseball Press Books, 1998).

Sumner, Jim L. “Eppa Rixey, Southpaw: A Virginian in the Major Leagues.” Virginia Cavalcade (Winter 1991): 133-142.

Swank, Bill. “Gavy Cravath.” Deadball Stars of the National League. Tom Simon, ed. (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s Inc., 2004).

Thorn, John, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman, eds. Total Baseball. 7th ed. (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001).

By far the most helpful source to me was a thoroughly enjoyable and informative telephone conversation with Eppa Rixey IV, the grandson of Eppa Rixey, during the fall of 2000. Without his kindness, many of the details of this article would be missing.

Notes

1 Martin Appel and Burt Goldblatt, Baseball’s Best: The Hall of Fame Gallery (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977), 323.

2 Operative No. 40’s detailed 11-page report is in the Eppa Rixey Files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

3 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 200.

4 Adam Bell, “Eppa Rixey: A nostalgic and fanciful look back at a life in the game . . . of the University’s very own member of the Baseball Hall of Fame,” The University of Virginia] Cavalier Daily (September 18, 1986). In Eppa Rixey Files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

Eppa Rixey

Born

May 3, 1891 at Culpeper, VA (USA)

Died

February 28, 1963 at Terrace Park, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.