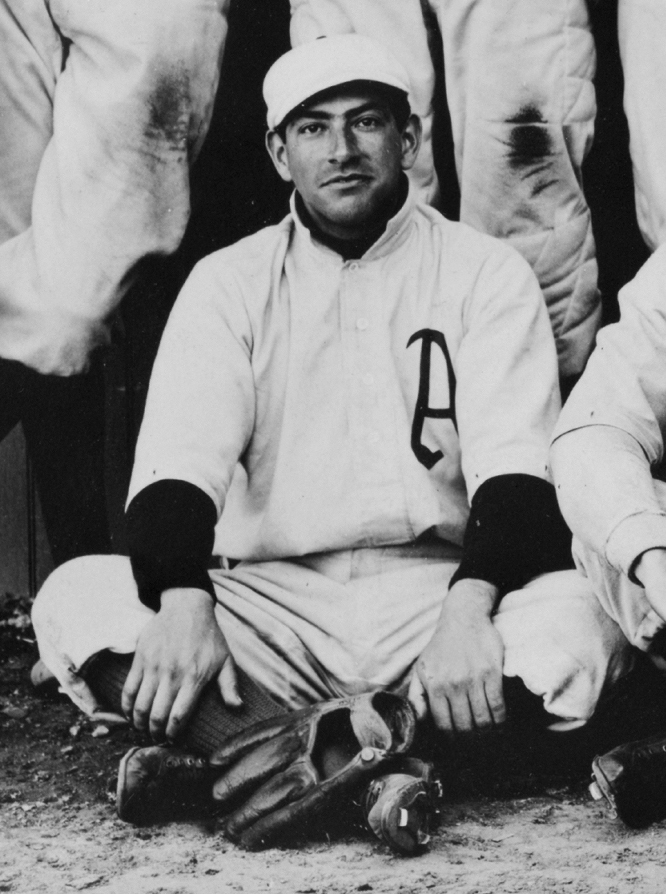

Luis Castro

Nearly half of all athletes in Organized Baseball today were born outside the 50 United States. At the turn of the 20th century, Luis Castro was one of the very few. He was the first Colombian in the majors (and remained so until 1974); the first Latino-born baseball player of the modern era; and the first to don a National or American League uniform, in 1902. That was his only major-league season, and he played in only 42 games, mostly as a second baseman. A few years later, he became the first Latino to manage a club in Organized Baseball.

Nearly half of all athletes in Organized Baseball today were born outside the 50 United States. At the turn of the 20th century, Luis Castro was one of the very few. He was the first Colombian in the majors (and remained so until 1974); the first Latino-born baseball player of the modern era; and the first to don a National or American League uniform, in 1902. That was his only major-league season, and he played in only 42 games, mostly as a second baseman. A few years later, he became the first Latino to manage a club in Organized Baseball.

Castro’s memorable place in major-league history has other origins as well. He was the first player to replace Napoleon Lajoie at second base when a Pennsylvania court ruled that Lajoie couldn’t play for the Athletics during the baseball war at the turn of the century. Before entering Organized Baseball, Castro played varsity ball at Manhattan College in New York City and was deemed to be one of the best college players on the East Coast.

He had one of the largest personalities in the game, standing out for his charm, geniality, and wit. Few left his company without a smile on their face. Castro was also one of the early baseball clowns. He performed skits on the coaching lines and chattered with teammates, opponents, umpires, and fans throughout each contest. Amusing stories of his antics were heard as far back as his earliest days at Manhattan College. Fans were attracted to his sideshow and loved to listen to his witty retorts and jests. But there was a dark side. In the end, Castro, who came from a well-to-do family and plunged into American sports and business ventures crashed with the rest of the country during the Depression. He had to seek assistance from the impoverished former ballplayers’ fund and died at what is now known as Manhattan Psychiatric Center.

Louis Michael Castro was born on November 25, 1876, in Medellin, Colombia, the second largest city in Colombia. This we know from the naturalization form he filled out in July 1917. But in recent years, controversy, fueled by Castro himself, has surrounded Castro’s actual birthplace. Was he a pioneering ballplayer of foreign birth, or was he actually born in New York City, as he maintained at a certain point in his life. Still, it seems clear that he was born outside the United States; otherwise, why would he file for naturalization?

As the encyclopedias indicate, Castro may well have been born Luis Manuel. However, when he entered the United States at the age of 8, the ship’s listing identified him as Louis. Castro was the son of Nestor Castro and Inez (Agnes) Vasquez. Nestor was a banker in Medellin who during political instability faced pressure from the government because of his wealth. Louis told a Philadelphia reporter (reprinted in the Baltimore Sun) in December 1902, “I’ll never go back home. It’s a little too exciting. If they don’t have a rebellion every few months the whole country gets an impatient idea that something has gone wrong. Then they begin a revolution to right it.”

The article continued, “While his father was conducting a bank in Colombia during one of the customary rebellions in that country, the government, unable to raise the expenses of war, descended upon his father with an armed force and a demand to turn all of his cash over to Colombia’s treasury. Refusals to oblige the government with little ‘loans’ often resulted in fires of ‘mysterious’ origin that destroyed the real estate of the disobliging citizen, who might consider himself lucky if a shot from a roadside some night did not end his career.” Castro told the reporter, “On this occasion my father remained firm in his refusal to give up his fortune. As he persisted in his stand the whole family [was] imprisoned in our own house, which was guarded outside and in with the armed body of government soldiers. In the end my father won.” In later years Nestor was involved in politics and journalism, and worked as a government official for Antioquia, the Colombian province in which Medellin was situated.

The instability of the political climate may have led Nestor Castro to relocate young Louis to the United States. They arrived in New York on October 14, 1885. Nestor returned to Medellin; there was work to be done to forge the new country. Within a year, the Colombian Constitution was signed, unifying the individual provinces, which up to then were semiautonomous states that formed the United States of Colombia. Louis grew up in New York City and remained in the United States for the rest of his life, save for a trip to Central and South America in 1922. Presumably, the family sent money to their son for living and educational expenses through his college years. In the fall of 1891, Louis, then 14, entered Manhattan College High School, a prep school attached to Manhattan College, a Catholic school then in Harlem. He attended both institutions (though they weren’t officially separated until later), leaving in 1900 without graduating to play ball. He resided on campus during his time there.

It was at the school that Castro began playing his first organized baseball games. In 1895, at 18, he joined the college’s main nine, despite still being a prep student. He was a key member of the squad through the 1900 season. At first Castro was a middle infielder — mainly shortstop — and outfielder. During his last few years at Manhattan, he was one of the team’s key pitchers, and was named by Sporting Life as one of the top college players on the East Coast by 1898. Among his college teammates who also played in the majors were Cy Ferry, Pete McBride, Doc Scanlon, Henry Thielman, and Jake Thielman. Among the school’s opponents during Castro’s era were various semipro clubs, the Cuban X-Giants, and the National League New York Giants.

Castro was dark-skinned, though clearly identified as white, with black hair and brown eyes. He was a righthander who stood 5-feet-7. A picture from his time with Portland of the Pacific Coast League in 1904 shows him to be trim and athletic looking, so comparing him to similarly built ballplayers puts his weight at about 155 to 165 pounds.

In 1897 Castro began playing ball for money with semipro squads in the New York area and New Jersey. During June through September of that year, he played for the Arlington team in New Jersey. Castro negotiated with Arthur Irwin, the former major-league player and manager and a respected figure in college circles, to join Toronto but instead signed with Utica of the New York State League after the college season in 1898. Castro signed about June 17 and played his first game in Organized Baseball on the 25th. He pitched and lost to Rome, 4-1, in an abbreviated five-inning game. The Syracuse Herald wrote, “He has speed and some deceptive curves, but is as wild as a bronco.” Castro was released by Utica in mid-July and joined Cooperstown in the Mohawk Valley League. On August 31 he joined rival Auburn for one contest, a complete-game loss to Rome, 8-3. In a total of 11 games in the New York State League, Castro made the rounds, playing at second, third, and shortstop and in the outfield as well as pitching.

In 1899 it became clear that Castro probably wasn’t going to make it in professional baseball as a pitcher; though he continued to work occasionally on the mound during his entire career. In 1899 and 1900 he played only for semipro teams — for North Adams, Massachusetts, and Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1898 and for West New York, New Jersey, and North Attleboro, Massachusetts, in ’99. He may have also played for Paterson, New Jersey. No longer in school, Castro joined Norwich of the Connecticut State League to kick off the 1901 season. He played with Norwich through early June and then joined several semipro clubs — West New York, Hoboken, New Jersey, and Meriden, Connecticut– before returning to the Connecticut State League with New London. In 52 games with Norwich and New London, Castro batted .221 while covering all the positions he did in 1898 in the New York State League. By the middle of 1901, major-league managers were noticing Castro’s work. The Boston Globe wrote, “It is said that manager (Frank) Selee (of the National League Boston Beaneaters) has lines out for pitcher Lewis [sic] Castro of Norwich, Conn., team.”

Instead of landing with Selee in Boston, Castro signed with Connie Mack and the Philadelphia Athletics in early 1902. He was brought in as a utility player, initially playing third base during the early parts of spring training. It was the second year of the battle between the upstart American League and the established National League. When the American League declared itself a major league after the 1900 season, it began offering lucrative contracts to lure talent from the National League. The bidding war particularly hurt the National League Philadelphia Phillies. They lost Napoleon “Larry” Lajoie, Bill Bernhard, Chick Fraser, and Elmer Flick to the crosstown Athletics. Washington lured Big Ed Delahanty away. The Phillies sought redress from the legal system. On April 21, 1902, a Pennsylvania court issued an injunction preventing Lajoie and the others from playing for a team in the state other than for the Phillies. The order was delivered on Opening Day, April 23, at Baltimore’s Orioles Park at the end of the seventh inning. Lajoie was pulled in the ninth and Castro took his place in the field; it was the rookie’s major-league debut. Philadelphia won, 8-1, but the game was decided before Castro came in. He didn’t come to bat. Unable to retain future Hall of Famer Lajoie, Mack initially slotted Castro as his replacement.

Castro performed well with the bat into June. He had a ten-game hitting streak. Teammates immediately nicknamed him Larry, a reference to his replacing Lajoie. Later in the season, Castro was dubbed Judge. Newspaper articles following a postseason celebration banquet for the pennant-winning A’s in October seem to be the first written reference to the nickname. Castro was a bit of a ham. Despite the fact that he was only a utility player for the club, he made a major speech at the banquet and acted as a sort of master of ceremonies. It is possible that he developed the nickname that night — as he was referred to as such in a Sporting Life article recapping the event. The nickname may have been meant to denote his talkative, powerful personality — in a fun, take-charge manner. He even regaled the guests with a Spanish song or two. Today, the reference sites list his nickname as Jud, a shortened version of Judge, but Jud isn’t found in any contemporary source, at least in print. It appears to have surfaced in 1943, when a writer used it. However, that doesn’t mean Jud wasn’t used informally during his career.

Unfortunately for Castro, his skills at second base were not major-league caliber. This became more apparent after his batting cooled off. As Mack biographer Norman Macht put it, “Lou Castro … turned more errors than double plays.” On June 11, Mack purchased Frank Bonner from Cleveland to take over second base. Even when Bonner was suspended for two weeks in July, Castro did not rejoin the lineup regularly. Instead, Mack brought in former New York Giant Danny Murphy, who was killing the ball for Norwich (.462 in 212 at-bats), on July 7; he would be the A’s main second baseman through 1907.

Later in July, Baltimore Orioles manager John McGraw jumped his club and took a large percentage of his players to the National League with him. American League president Ban Johnson asked the other league franchises to send men to fill the Orioles’ roster. Mack offered Castro but new Orioles manager Wilbert Robinson didn’t want him. Castro remained with the A’s through the rest of the season, appearing in a total of 42 games, mostly at the beginning of the season, and batting .245. Philadelphia won the pennant but there was no World Series; that tradition started the following year. After the season, Castro barnstormed with some teammates for extra cash.

Another interesting, confusing, and mildly significant (or perhaps insignificant) event in Castro’s career occurred in 1902. In an interview in December, he claimed to be the nephew of Cipriano Castro, a military strongman in Venezuela, who as president of the country angered the United States and other nations early in the 20th century with his dictatorial actions. In truth, the claim may have come from the reporter. Nevertheless, Castro played off it for years; bear in mind that much of his reputation stems from his clowning. No one has been able to emphatically confirm or deny the relationship. (As all good tales go, future writers have skewed the details and played up the story — often mixing up the particulars, such as stating that they were cousins or other such relations.) The story led to yet another nickname when Castro later joined Portland. Upon hitting the West Coast, he was dubbed “The President of Venezuela.” Perhaps in a rare serious mood, Castro finally told an Atlanta Constitution reporter in February 1909 that his claim was untrue. Castro “denies all relationship to the deposed president,” the article said.

In recent decades, Castro has received attention out of proportion to his actual accomplishments on major-league diamonds. The attention stems not from his work on the field but from the very essence of who he was. He was the first Latino major leaguer born outside the United States. Esteban Bellan, a Cuban, performed in the National Association, the precursor to the National League, for three years in the 1870s, but the National Association is not universally viewed as a major league. Still, perhaps Bellan is a more significant figure than Castro. Both Castro and Bellan, though foreign-born, were reared and learned to play ball in the United States and developed their reputations first at American colleges — Bellan at St. John’s College (now Fordham University) and Castro at Manhattan. (Another player, Sandy Nava, was identified as a Latino despite the fact that he was born in San Francisco. Nava, a major leaguer from 1882 to 1886, had dark skin and a last name that identified him as being of Latin descent.)

Unlike most of today’s Latin ballplayers, Castro (as well as Bellan) first learned to play the game in the US. He was not the product of the fertile Latin ballfields that fill major-league rosters in the 21st century. He was thoroughly Americanized, having lived in the country since his youth. And unlike many later Latin players, Castro, with a darker tint to his skin than most of his teammates, was still clearly adopted as white and suffered no significant racial harassment. The fact that he had a college degree may have played a role in people’s perceptions. He was well-liked everywhere, even in the South. His personality also played a major role in his acceptance. The Atlanta Constitution wrote in 1907, “There is no player in the Southern (Association) today more universally liked than Count Louis Castro, the Atlanta shortstop, and this popularity is due in a great measure to the never-ceasing flow of good humor which he is fortunate enough to possess. … Castro is one of the most brilliant fielders in the league, and gets away with some sensational work in every game. He is a consistent player, never lets down and is a great man for a baseball team, with his abundant supply of ginger, and an over-flowing line of talk while in action…He is the comedian of the league, and hardly a day passes that he does not pull off some funny performance on the coaching lines or on the field. He is so serious about it all that he reaps great success, and it is a safe bet that he would make good on the stage in this line of work.”

Regardless of any distinctions, there is no denying that Castro was the first foreign-born Latin to play in the major leagues in what is typically referred to as the modern era. He had a Latin surname and was understood throughout his career to hail from outside the United States (though, some were confused in recent decades). He was identified by writers at various times as a Spaniard, Colombian, Venezuelan, or Cuban. Later, when he managed two Southern clubs, Castro may have been the first Latin to do so in Organized Baseball. Castro played in the Connecticut State League in 1901 and began a precedent by which many future Latin ballplayers funneled into Organized Baseball through that league. For example, the Cincinnati Reds tapped the Connecticut circuit in 1911 to kick off a long and significant wave of signing Cuban ballplayers.

This is not to say that Castro was a pioneer who opened the floodgates for poor Latin athletes. It would be another decade before Latin players started to make headway into the game, mostly Cubans. As the numbers rose, so did controversy — especially as skin tones became darker. The Washington Senators signed many Latins in the 1930s and ’40s, but they were virtually the only team to do so then. Talented dark-skinned Latin players wouldn’t be fully embraced until the 1960s.

Castro didn’t fit in the A’s plans for 1903 and he was released. Arthur Irwin signed him for his Rochester club of the top-tier Eastern League. He didn’t last long though, being fined and suspended in early June for insubordination. Trying to force a trade to Detroit, Castro refused to play for Rochester. Irwin sold him and outfielder Jack Hayden to Baltimore of the same league for $2,000 on or about June 7. The Washington Post wrote, “The Baltimore team has been greatly strengthened by the acquisition of several new players. Pitchers Snake Wiltse and Fred Burchell, outfielders [John Kelly] and Hayden, and infielders [Stephen Griffin] and Castro have braced up the team considerably. The boozers have been chased and subdued.” Castro put up the best batting numbers of his career. In 111 games in the Eastern League, he batted .329 and led the league with 23 triples, while playing every infield position, but mainly at second base.

Over the winter, the Orioles offered Castro a contract with a pay cut of $50 a month. Unhappy, the ballplayer took some advance money from Portland of the Pacific Coast League in December, signed a contract calling for $2,000, and was named team captain. Hayden signed with Portland as well. In essence, Castro jumped his contract. It became a major to-do because the PCL was negotiating to join Organized Baseball. The issues surrounding Castro, Hayden, and Frank Dillon, who had signed with both Los Angeles and Brooklyn, could potentially disrupt the entire negotiation process. The PCL owners met, signed the National Agreement and voted to return the players to their Eastern teams. The Portland and Los Angeles owners, however, didn’t see it that way. The disagreement still loomed as the season neared, threatening the merger. In the end, Dillon and Hayden returned east but Castro refused. Portland eventually worked out a deal for the player.

Castro’s ethnicity seemed to draw more attention on the West Coast than elsewhere, or perhaps the newspapers were just a little more politically incorrect. The Daily Californian, for example, wrote that Castro “walks like a Mexican” and that “he resembles a toreador and the bleacher boys call him ‘Bullfighter.’ ” Castro received heavy criticism in Portland as the season began. The Morning Oregonian commented on April 20, “Portland’s captain is of the farce comedy order. If one did not know that Louis Castro was the nominal leader, it would never be suspected. He is not a natural director and things take their course in the most haphazard manner. The cases of office bear heavily on him for all his apparent inefficiency. He is fielding poorly and hitting in indifferent form.” Perhaps the paper had a point, as Castro was soon relieved of the captaincy.

It was a contentious season; some felt that Castro didn’t live up to his hype as a former major leaguer who had killed the ball in the Eastern League. He appeared in 112 games for Portland through mid-September, batting .265 while playing the middle infield, mainly shortstop. He was released without warning soon after hurling a ball at an umpire in frustration. Portland finished last in the league. In October, Castro sued the club for $775 in damages for termination of his contract. The original telegram from the club offered a set sum for the season. Castro argued that he was due the difference. Portland countered that all baseball contract amounts are assumed to be based on a monthly figure. The team won out. Around this time, Castro married a Vermont native named Margaret about seven years his junior. It appears that they didn’t have any children.

In January 1905, Art Irwin again signed Castro — this time with Kansas City of the American Association, which Irwin was now managing. Castro’s salary was stated to be $325 a month. In 146 games, he hit .263 while playing first base, third base and the outfield. Castro became good friends with teammate and former major leaguer Suter Sullivan. The two were said to be inseparable. Castro claimed that Sullivan was his personal manager and trainer.

Just before Opening Day in 1906, Castro was traded to Nashville of the Southern Association with outfielder Jack Gilbert for Billy Phyle. Castro started at shortstop and even pitched a little for Nashville. Around August 19, he was loaned to Birmingham for the remainder of the season for a $500 payment. Both of Birmingham’s shortstops had come down with typhoid fever and the club needed a replacement for the final pennant push. Irate league opponents objected to the deal. They protested individual games Castro played in and ultimately questioned the legitimacy of the championship. Birmingham was the front-runner anyhow (they won the pennant by eight games); this obviously sparked competitive ire. The fact that Castro initially hit well only poured salt in the wound. Also, “loaning” a ballplayer was considered an illegal transaction. Publicly, Birmingham and Nashville agreed on an outright sale of Castro for $1,000. But when tempers settled over the winter, Castro was quietly returned to Nashville. He batted .233 in 122 games for the two clubs. Over the winter in Birmingham, Castro began working as an undertaker. Rumors of his retirement from baseball soon followed. In the South he picked up yet another nickname, “Count Castro.” As he lived in the South through World War I, this nickname was used more extensively than the others, especially in Atlanta, by the Constitution, where Castro lived for a decade beginning in 1907.

In January 1907, after returning to Nashville, Castro was immediately traded to Atlanta of the Southern Association, probably to stave off any lingering criticism. However, Castro still hadn’t decided if he was returning to the diamond and he reported to the club late despite signing in February. At one point during the season he was described as using the longest bat in the “entire South.” In late July, Castro knocked a homer to win a game. The Washington Post exclaimed, “For swatting out that home run in the New Orleans series with Atlanta, shortstop Castro of the latter team was showered with $21.20 in change, one hat and two pairs of shoes.” Nevertheless, in September he was placed on waivers but never officially released. Atlanta won the pennant by 3½ games. In 114 games, Castro batted .228.

Castro’s personality won him a lot of fans in the South. Sporting Life wrote in May 1907 from Memphis, “The unique spectacle of a visiting player, unknown personally to home fans, being presented with diamond studded buttons, was witnessed here on the 11th … for ‘services rendered in amusing spectators with the wittiest line of coaching and the best lot of ball playing ever seen.’ ” Castro was one of the earliest baseball clowns in the tradition of Nick Altrock and others. One time in Atlanta, he donned a dress and “widow’s hat” and paraded around the field with a baby carriage, offering kisses to all. It doesn’t appear that he did his clowning while in the majors or it would be more widely known. He treated minor-league audiences to his antics, barbs, and jokes for years. It became one of the highlights of the game when Castro took his place along the coaching lines. Fans eagerly awaited his return to their city.

That Castro was known throughout baseball for his personality might not be notable except for the fact that it was commented on time and again in a wide assortment of newspapers and by numerous reporters and followers of the game. The adjective probably used most often was “witty.” He was quick-witted and amused most of the people he came into contact with. He was described as a “live wire” with plenty of “ginger.” He was also a constant practical joker, nailing teammates’ shoes to the floor and the like. Another typical adjective was “genial.” He was said to have a “sunny disposition.” As one reporter stated, “He smiles at every opportunity.”

Castro returned with Atlanta in 1908, the first and only time he was held over by a professional club. By July, he wasn’t being used very much, instead spending a good deal of time helping to coach the players and, of course, entertaining the crowd. In early August, he was placed on waivers but pulled back when outfielder Ginger Winters fell to injury. On the 19th, he was released anyway. The Atlanta Constitution wrote, that “Count Louis Michael Castro” was being let go to make room for a pitcher, Phil Sitton, and added, “The release of Castro was not done without considerable comment on the part of the fans, who have always liked the genial Venezuelan.” The Constitution was overjoyed to hear of his return on September 6 when another player, outfielder Roy Moran, went down: “Have you heard the good news? It seems too good to be true but it is just the same. Count Louis Michael Castro will be back in the game at his old accustomed place on short today. … Castro may not be a heavy hitter but no one can say that he is not always in the game from start to finish and he can field with any of them and when it comes to using gray matter there are few who have anything on Castro. … Won’t it look natural to see the Count at his old place and see his antics on the coach lines and hear his ready puns all through the game?”

In 82 games with Atlanta, Castro hit a meager .173. In September, between gigs with Atlanta, he umpired local games. In October and November, he headed a barnstorming club known as Count Louis Castro’s Insurgents, filled mainly with Southern Association players. Over the winter, he fielded offers from several clubs, some of whom wanted him as a manager. He lived and worked, still as an undertaker and mortician, in Atlanta, though, and didn’t want to stray too far. Castro was ecstatic in February 1909 when nearby Augusta of the South Atlantic League extended an offer to him to manage the club. The Constitution wrote, “He was beaming over with smiles and his usual supply of wit seemed to be doubled.”

During the 1909 season, Castro’s usual good nature failed at times due to the pressures of managing, especially when it came to umpires. At least twice, rows with the men in blue resulted in forfeitures. Augusta finished in third place overall but won the second half, securing a spot in the playoffs. In 121 games at second base, Castro hit .195. On September 15, Augusta faced Chattanooga. After the contest Chattanooga’s manager, Johnny Dobbs, accused Castro and his crew of poisoning them when a bunch of his players became ill after drinking from a water bucket. Castro, indignant, blasted back that Dobbs was merely looking to avoid the coming postseason series. With his usual humor, Castro signed a subsequent telegram or two “Poisoner Count Castro.” But Castro’s Augusta team lost the postseason series to Chattanooga four games to two. In December, Castro was given his unconditional release, probably at his own behest. He was changing occupations and retiring from baseball, at least temporarily. In 1910 and ’11, he worked in Atlanta as a beer salesman for Falstaff, a St. Louis brewing company.

Portsmouth of the Virginia League hired Castro as player-manager for the 1912 season. The club finished fourth, 12 games behind Roanoke. In 130 games at second base, he hit .247 and led the league with 12 home runs. He seemed to get faster with age, stealing a total of 42 bases in 1909 and 1912. In November, he re-signed with Portsmouth; however on March 6, 1913, he injured his arm refereeing a boxing match between Battling Nelson and Frank Whitney in Atlanta. The injury ended his playing career. Portsmouth immediately replaced him as manager as well. Castro was 35. He promoted boxing matches in Atlanta from 1912 through 1915. He set up a boxing ring at a skating rink. He also refereed matches during that span.

In November 1913, it was announced that Castro had signed with New Orleans as a player-coach for the 1914 season. The club was interested in the marketing potential of his clowning antics. It appears, though, that he never joined the club. The split with Portsmouth must have been contentious. Despite not using him, they reserved Castro at the end of 1913, listing him as suspended. He was still listed as reserved at the end of 1914. The latter year, he umpired local games in Atlanta.

In 1913, Castro also managed the Motordome in Atlanta, a motorcycle race track. In September, he opened the Diamond Saloon on Luckie Street, across from the Piedmont Hotel. He spent part of 1914 in Nashville but returned to Atlanta. In 1915, he managed two hotels in Griffin, Georgia. In February 1916, Castro was charged with illegally dispensing whisky at the saloon but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence.

Near the end of World War I, Castro moved to Jacksonville, Florida. By the early 1920s, the Castros moved to Philadelphia. In 1922, he headed a group of investors who looked to purchase the Jersey City club of the International League and move it to Providence. The venture didn’t come to fruition. On March 17, 1926, Castro pleaded guilty in a Philadelphia court to failing to file income tax reports for 1922 and 1923 on income of $30,370. He was fined $2,500.

By 1930, the Castros were living in the New York City borough of Queens. Despite the wealth of his family and his various business interests, the Depression apparently hit Castro hard. In 1937, he applied for financial assistance from the Association of Professional Baseball Players of America. He received some benefits — verifiable in 1941 and probably earlier as well. This may explain why little is known about Castro’s life after the mid-1920s. He fell off the grid, so to speak, like so many Americans fighting for daily sustenance during the Depression.

On September 24, 1941, Louis Castro died at Manhattan State Hospital, a psychiatric facility on Wards Island, at the age of 64. He was buried at Mount St. Mary’s Cemetery in Flushing, Queens.

Author’s Note

Castro’s application for citizenship claims that he was 5-feet-10½ and weighed 175 pounds. This seems unlikely as he was identified more than once in contemporary newspapers as “little” or otherwise described as diminutive. The 5-feet-7 cited in the encyclopedias seems much more realistic.

The Castros, Louis and Margaret, were married around 1904, as noted in the 1910 US Census (Atlanta). No listing of children was found in the 1930 Census (Queens, NYC). Hence, I concluded that they couple had no children. This could readily change if other data is uncovered, such as a citation in the 1920 Census (Unknown).

Adrian Burgos wrote in Playing America’s Game that Castro may have gotten his nickname “Judge” from his father’s occupation. The basis for this was a reference during a Philadelphia A’s postseason celebration in October 1902 in which a “Judge Louis M. Castro” gave a speech at the affair. The author took the “judge” to be Castro’s father when it fact it was Castro himself.

Castro applied for citizenship on July 10, 1917. Forty years old at the time, he was living in Jacksonville, Florida. In the document he clearly noted his birthplace as Medellin, Colombia. In subsequent documents he listed his birthplace as New York — in a passport application in 1922 and in the 1930 US Census. This has led to confusion about his birthplace. It may be, as researcher Gary Ashwill has surmised, that Castro was not granted citizenship for some reason and feared reprisal. Hence, he eliminated the question of his nationality by claiming an American birth from that point on.

In the 1930 US Census, Castro oddly listed his occupation as baseball player. At the time he was 53 years old, so that is unlikely. The difficulty in tracing him during this time suggests, among other things, that he had no connection with baseball. Listing his occupation as such may suggest that Castro was unemployed and already hitting hard times.

Sources

Thanks to Ray Nemec for opening his vault of minor-league numbers for the Louis Castro biography.

Much appreciation to Rory Costello for sharing some insight into Castro’s life and career.

Dr. Gilberto Garcia went out of his way to get me his article when I was having difficulty accessing it. His efforts are much appreciated.

Ancestry.com.

Ashwill, Gary, Agate Type website.

Atlanta Constitution, 1907-16.

Baltimore Sun, 1902-1904.

Baseball-reference.com.

Boston Globe, 1900-01, 1926.

Boxrec.com.

Brooklyn Eagle, 1900.

Burgos Jr., Adrian. Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Coshocton Daily Age, Ohio, 1903.

Daily Californian, 1904.

Daily Kennebec Journal, Maine, 1903.

Galveston Daily News, 1906.

Garcia, Gilberto, “Louis ‘Count’ Castro: The Story of a Forgotten Latin Major Leaguer,” Nine, Volume 16, Number 2, Spring 2008, pp. 35-51.

Genealogue.com.

Gojaspers.com.

Hartford Courant, 1901-02.

Herbert, Ian. “Debating Louis Castro: Was He the First Foreign-Born Hispanic in Major Leagues?” Smithsonian.com, September 1, 2007.

Heritagequest.com.

Irish World and American Industrial Liberator, New York, 1892.

Janesville Daily Gazette, Wisconsin, 1903.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. 2nd ed. Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1997.

Los Angeles Times, 1904-14.

Macht, Norman L. Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Morning Oregonian, Portland, 1904.

New York Times, 1895-1901, 1921.

New York World, 1899.

North Adams Transcript, Massachusetts, 1899.

North American, Philadelphia, 1898-99.

Oakland Tribune, 1904.

Oswego Daily Palladium, New York, 1898.

Petersburg Daily Progress, Virginia, 1912.

Racine Journal-News, Wisconsin, 1915.

Retrosheet.org.

Sanchez, Jesse, “Uncertainty Swirls around Louis Castro: Legendary Latin American Ballplayer as Mysterious as Ever,” MLB.com, April 23, 2007.

Sporting Life, 1898-1914.

The Sporting News, 1902-03.

Surak, Amy, Archivist at Manhattan College, was very helpful in clarifying a few issues relating to Castros time at the institution.

Syracuse Herald, 1898-99, 1911.

Syracuse Post-Standard, 1902.

Trenton Times, New Jersey, 1903.

Washington Post, 1902-07.

Wikipedia.org.

Full Name

Luis Manuel Castro

Born

November 25, 1876 at Medellin, Antioquia (Colombia)

Died

September 24, 1941 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.