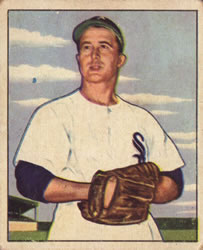

Mickey Haefner

Mickey Haefner was a decent lefty pitcher for an up-and-down Washington team from 1943 into 1949. He won 10 or more games five seasons in a row, topping out at 16 in 1945. No taller than 5-foot-7 (not 5-foot-8, as he himself confirmed in 19431), his nickname was “Itsy-Bitsy.”

Mickey Haefner was a decent lefty pitcher for an up-and-down Washington team from 1943 into 1949. He won 10 or more games five seasons in a row, topping out at 16 in 1945. No taller than 5-foot-7 (not 5-foot-8, as he himself confirmed in 19431), his nickname was “Itsy-Bitsy.”

Haefner featured a knuckleball, although he frequently threw a fastball and curve, all delivered sidearm.2 When the Senators fought the Tigers for the 1945 AL pennant, Haefner was part of a rotation that included four starters who threw knuckleballs. In 1948, renowned Washington Post columnist Shirley Povich called him “my favorite ball player.”3

Yet one pitch in a 1946 postseason exhibition game tends to bring up Haefner’s name more often than anything else. That fateful pitch hit Ted Williams’s right elbow, resulting in lingering soreness that was blamed at least in part for Williams’s poor performance in the ’46 World Series.4

Milton Arnold Haefner (the first syllable pronounced hay, not half) was born on October 9, 1912, in Lenzburg, Illinois, about 40 miles southeast of St. Louis. He was one of 13 children of the former Laura A. Frazer and her husband, Casper R. Haefner. Milton’s father was brought to America as a child from the German state of Bavaria. Laura Frazer, of Scottish and English descent, was born in southern Illinois.5 She had her first child in 1906 at age 17. Although his father spoke German, young Milton never became fluent in the language.6

Milton was his mother’s third child. He had an older sister Ella, the first-born, and a brother Harry, born in 1909. Two of Casper and Laura Haefner’s children died in infancy, but Milton eventually had four brothers and six sisters after the last sibling who survived to adulthood, Joyce, was born in 1931.7 There were many mouths to feed.

Lenzburg is in what was then a coal mining region in St. Clair County, Illinois. Indeed, Casper Haefner worked in the mines, as did his male children when they were old enough. Milton began working in the mines after eighth grade to help support the growing Haefner family.8 “Milt and his two brothers were on a shovel brigade,” according to a Sporting News story in 1943, “and 54 tons a day was normal production for the trio.”9 He played baseball with his brothers in what free time they had.

People in Lenzburg who saw young Milton walking with his baseball glove tied to his belt began calling him “Mickey” after a cartoon-strip character that did the same.10 The nickname stuck.

As a teen, Mickey began to show some talent pitching for a mine company team. A lack of demand closed the mines in St. Clair County each year on April 1 for an extended period.11 Left unemployed, Mickey’s brother Harry and later his younger brother Carl had begun playing for semipro baseball teams in the area, so Mickey “figured that if they could pick up money for playing ball, it should be easy for him,” according to The Sporting News.12

Coincidentally, two of Haefner’s fellow knuckleball starters with the Senators, Roger Wolff and Dutch Leonard, also were from southern Illinois. Leonard’s father was a miner, too.

A young woman from New Athens, Illinois, who worked at a restaurant near the ball field where Mickey’s semipro teams played13 often came out to watch him pitch. They began a courtship.14 On June 20, 1936, in New Athens, Mickey and Lucille Mueller wed.

With the mines closed, Mickey traveled north to Chicago and took a job at the American Tank Car Co., a railroad repair shop, which also had a team in a Sunday industrial league.15 He kept pitching in the league after he was laid off, while working eight-hour shifts on farms in nearby Hammond, Indiana. He pitched three times a week in a semipro league there.

The results were good enough that Haefner concluded he could make it as a professional pitcher.16 A Cardinals scout apparently agreed, but before a signing offer could be made, Haefner developed an ear infection and had surgery to remove the mastoid bone behind an ear. Its removal temporarily affected his balance and kept him off the pitcher’s mound. The scout moved on.17

Undeterred, Haefner returned to pitching as his balance issues cleared up, when his work schedule in the St. Clair County mines and the foundries and farms in the Chicago area allowed.

While he was pitching for a semipro team near Chicago, Mickey and Lucille had a son, Milton Alvin Haefner, who was born in Hammond in 1937. The couple eventually had two more children, son Nolan, born in 1945, and daughter Ruth, in 1952. Young Milton, who also came to be called “Mickey,” would attend games in St. Louis when the Senators were in town.

Not long after, the player-manager of Haefner’s Hammond team, former major-league lefty Tim Murchison, offered Haefner $100 a month to pitch for Tallahassee in the Georgia-Florida League. Murchison had agreed to manage that club in 1938. At age 25, Haefner began his career in Organized Baseball there. He won 15 games and threw 234 innings. The years of pitching for semi-pro teams had prepared him well. His 2.5 walks per nine innings demonstrated the good control he displayed throughout his pro career, despite the normal unpredictability of the knuckleball he had added to his repertoire.

Tallahassee had an affiliation with the Dodgers, but nothing indicates that the team had any interest in Haefner. In 1939, he moved on to Deland in the Florida State League, where he had an outstanding season (24-9, with a 2.32 ERA in 272 innings). He threw three complete games in the league playoff series, winning two and losing the other, 2-1, on an unearned run.

His manager there for a time, Lee Meadows, “gave him his first real break,” The Sporting News wrote, and taught him “that slippery, slithery sidearm sinker.”18 This pitch might have been more than just a sinker. Haefner admitted that he sometimes threw a spitter in the minors but was afraid to use it in the majors after umpire Bill McGowan caught him doing it during Haefner’s rookie year. In any case, Haefner considered his curveball his best pitch.19

Meadows, who served as bird-dog scout of sorts for the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers, recommended Haefner to Mike Kelley, the longtime manager and then owner. “There never was a grander friend to a ball player,” Haefner said of Kelley. “He gave me a square deal…. All he asked was the same treatment he gave you,” Haefner told the Sporting News about his three seasons with the Millers. He also spoke highly of his Minneapolis manager, Tom Sheehan. “If you pitched hard for him, he was with you 100 percent.”

Haefner won 14, 12, and 18 games for a middle-of-the-pack team playing in compact Nicollet Park, yet his short stature put off most big-league scouts. As rosters lost more players to the war, however, Washington’s “Old Fox” Clark Griffith liked what he heard about Haefner enough to pay Kelley $20,000 for somebody a lot like Griffith himself.20 The Senators’ owner stood 5-foot-6, yet was a star pitcher decades earlier.

The longtime umpire and team executive Billy Evans, who was president of the Southern Association at that point, wrote to Griffith, praising him for acquiring Haefner. “Forget about his size,” Evans said in his letter. “He has the best control of any lefthander you ever saw.”21

Haefner had tried to enlist in the military after America entered the war but was rejected because of his mastoid-related hearing problem. For years, people in his hometown were under the impression that he avoided service because he was playing baseball.22

“Maybe it took a world war to get me into the major leagues,” Haefner told The Sporting News, “but I’m not kicking about that.”23 He soon proved he had the talent to last beyond the war years.

After the 1946 season, Haefner was a part of an AL “all-star” team assembled quickly to keep the pennant-winning Red Sox sharp as they awaited the winner of a three-game NL playoff between the Cardinals and the Dodgers. The team included Joe DiMaggio, who played a game in a Red Sox uniform, as his Yankee pinstripes had not arrived in time.

On October 1, in the first of three games against Boston, Haefner hung a curve that hit Williams, who was looking for the knuckler, on the joint of his right elbow. The pain was bad enough that the Boston slugger had to leave the game. Although X-rays showed no break, Williams’s elbow swelled up. He didn’t play in the other two exhibitions.24

Against the Cardinals in his only World Series, the Splendid Splinter famously went just 5-for-25 with no extra-base hits, as the Red Sox lost to St. Louis. “The curse of Mickey Haefner” was born.25 Williams conceded years later that his injured elbow played a part in his shockingly subpar performance.26

Haefner had one other, if obscure, niche in the record book: a major-league record that still stands. On July 3, 1943, Ewald Pyle had relieved the Washington starter, Ray Scarborough, and pitched four no-hit innings. Haefner, a 30-year-old rookie, followed Pyle and held the St. Louis Browns hitless during the seventh, eighth, and ninth. This was the first time in big-league history that two relievers on the same team had held the opposing team hitless for three or more innings each. A late Washington rally made Haefner a winner, to boot.

The Pyle–Haefner performance was matched in 2015 by Diego Moreno and Adam Warren of the Yankees, against Texas. In an era of heavy bullpen use, this record soon could be matched again or surpassed. But it remains a first.

Despite the familiar “last in the American League” trope, the Senators finished second twice and fourth once during Haefner’s tenure. Although Washington was never really in the1943 pennant race, the team finished runner-up, albeit 13½ games behind the first place Yankees. Haefner wasn’t a member of the starting rotation until late July. In fact, he started just one game in late April and another on June 20, where he went only two innings and lost, dropping his record to 2-2. A loss as a starter on July 24 and a complete-game loss on July 29 left his record at four win and four losses. After July 29, he pitched seven complete games and hurled seven innings in each of the two starts where he did not go the distance. He finished his rookie year with an 11-5 record and a 2.29 earned run average.

In another wartime surprise, the Nats lost 90 games and fell to the basement in1944 — the first time in Griffith’s long tenure that happened. It certainly wasn’t Haefner’s fault. Three of the four starters who threw knuckleballs — Haefner, Leonard, and Johnny Niggeling— together won 36 games with a combined ERA of 2.82. Wolff, the fourth knuckleballer, had an awful year (4-15, 4.99), but his turnaround helped make the difference the following season.

Nobody expected the Nats to contend in 1945. The wire services wrote that it would be an achievement if Washington finished as high as sixth. But thanks to a couple of players making the most of their chance as big league regulars for the first time — George Myatt and George Binks— and Wolff’s emergence as a 20-game winner, Washington stayed in contention until the last week of the season. Haefner won 16 games, behind Wolff’s 20 and Leonard’s 17. The Senators finished second, a game and a half behind the Tigers. This was the last time the original Washington franchise would be in a pennant race.

With the war over and all the stars back in 1946, Haefner had another good season, lowering his ERA to 2.85 and winning 14 games for a fourth-place team. The Senators fell to seventh place with 90 losses in 1947, but Haefner held his own. By 1948, it was becoming clear that Griffith, with a tight budget and a bare-bones farm system, had a hard time putting a competitive team on the field. Haefner was plagued with a serious sinus problem that ended up requiring surgery. He was shut down in early September.

On a team that lost 97 games, 1948 was the worst season of Haefner’s career. The lone highlight was the June 4 matchup at Griffith Stadium with Bob Feller, who pitched 11 shutout innings. Haefner did him one better, blanking the Indians on five hits over 12 innings. Cleveland won after he left, breaking the scoreless tie in the 15th.

The 1949 season started well for Haefner. He won five games in a row after losing his first start, 2-0. He pitched four complete games and didn’t suffer his second loss until June 14. On May 10, during Washington’s nine-game winning streak,27 Haefner pitched a one-hit shutout over Cleveland, the defending champions, winning 1-0. The lone hit was a one-out single in the first by Larry Doby.

With a strong wind blowing in the hitters’ faces, “I didn’t use my knuckler much,” Haefner said of his May 10 performance. “Just threw the fastball and curve and dared ’em to hit it.” He insisted the one-hitter was not even the best game he had pitched in the majors, ranking his five-hit shutout over Feller and Cleveland, 1-0, on July 20, 1947, as being better. The conditions that day were ideal for hitters, Haefner said.28 It’s no wonder that the Indians reportedly tried to acquire Haefner several times.29

After the great start, little went right for Haefner. He didn’t make it past the fifth inning in four starts, losing three times and giving up six runs in three innings in another. Eventually, he found himself in the bullpen, so that another lefty, Mickey Harris, acquired from Boston, could start. Haefner pitched in relief five times between June 22 and July 4, blowing a lead and losing the game on July 4.

On July 7, starting against the Red Sox on a damp night in Washington, Haefner was knocked out in the first inning. With the bases loaded, he misplayed a dribbler off the bat of Boston pitcher Chuck Stobbs. Griffith was incensed. During a rain delay, he went to his stadium office and typed out a press release firing Haefner for an “indifferent effort.” Griffith said Haefner had pitched his last game for the Senators.

After the game, Haefner remained calm and declined to criticize Griffith, other than to insist he had given his best on the field and always had. He said the ball on which he made the error was wet and had slipped out his hand. “I’m not going to say anything against Mr. Griffith,” Haefner said. “He has always been fair to me, and I have a lot of respect for him.”30

Because Griffith had put Haefner on the waiver list in June before withdrawing his name when other teams tried to place a claim, the Old Fox could not ask to waive the pitcher again until July 20. So Haefner was effectively suspended until the White Sox, who were behind Washington in the standings at that point, immediately claimed Haefner for the $10,000 waiver price.

He was 5-5 after losing his last game in Washington. That left Washington at 32-41 in sixth place. From then on, the team was 18-59 and finished last. Griffith made it plain later that he regretted letting Haefner go. He and the pitcher had an amicable telephone conversation on July 15 “and came to a mutual understanding. There is no ill feeling,” Griffith said. He even paid Haefner a $1,000 bonus that had been based on the pitcher’s win total, an incentive that Haefner hadn’t reached. “I’m giving him the benefit of the doubt.”31

Haefner spent the rest of the 1949 season and part of 1950 with the White Sox, but on August 8, 1950, Chicago sold him to the Boston Braves. His stint in the NL did not go well: in two starts and six relief outings he gave up 15 runs in 24 innings.

At the end of the 1950 season, the Braves sent Haefner to Seattle in the Pacific Coast League for pitcher Jim Wilson and cash. The trade ended Haefner’s big-league tenure. During his eight seasons, Haefner topped 225 innings pitched three years in a row. He completed 91 of his 179 starts. He threw 13 shutouts. The Senators typically matched up Haefner with the other team’s ace.32

On May 14, 1951, Seattle sold Haefner to the Birmingham Barons, where the 38-year-old enjoyed a few last moments of mound glory. He won a Southern Association playoff game, 9-1, on September 19, pitching the Barons into the Dixie Series against Houston. Then, he beat the Texas League champs twice to win the title, including the clincher in Houston on October 4 before 10,500 fans. He retired from pro ball after that season.

Haefner returned home to New Athens and opened a tavern, but the business wasn’t successful. Thus, he began working as a day laborer, sometimes on barges on the Mississippi River. He “had trouble finding employment,” his daughter, Ruth Markham, wrote in an email, “due to lack of education and the perception that we were rich because he had played in the major leagues.”33 He was a member of the laborers union and was inducted into the Freemasons in 1947.34 Years after he left baseball, he was among the players from the 1940s who began receiving small pension payments.

On weekends, Haefner resumed pitching for the semipro New Athens Merchants, one of the teams for whom he had pitched on and off in the decade before he began his professional career. His last days with the team were in 1954.35

Haefner suffered a severe stroke in January 1989 and spent his final years in a nursing home in New Athens. His daughter Ruth said that Whitey Herzog, who grew up in New Athens and played on the Merchants at least one off-season with Haefner, worked with the Baseball Assistance Team to cover the cost of his longtime friend’s care.

Mickey Haefner died on January 3, 1995, at age 82. Herzog and Rich Hacker, a longtime coach for the Cardinals and Blue Jays, served as pallbearers at Haefner’s funeral.36

Haefner and his wife, who died in 2003, are buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in New Athens, Illinois.

“I never had much chance to go to school. I’ve learned a lot listening to folks that know more than I do,” Haefner told The Sporting News in 1943. “I’ve learned that you are equal to what you produce, and the world takes you at the value you establish. That makes you work just a little bit harder to raise your value.”37

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the help of Mickey Haefner’s children, Ruth Markham and Nolan Haefner, Mickey’s grandson Kurt S. Haefner, and Steven Woodward of the New Athens Historical Society with this essay.

The author also thanks Cassidy Lent, Manager of Reference Services, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used:

BaseballReference.com

Retrosheet.org

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Evening Star (Washington, D.C.)

Notes

1 Burton Hawkins, “Introducing Some of the Nats’ New Pitchers,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), March 16, 1943: A14.

2 Frederick G. Lieb, “Leading Pitchers Favor Uniform Mound – But High,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1946: 10. Confirmed in author’s telephone conversation with Kurt S. Haefner, Mickey’s grandson, January 14, 2022.

3 Shirley Povich, “This Morning” column, Washington Post, March 3, 1948: 19.

4 Ben Bradlee, Jr., The Kid (Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2013): 268-269.

5 American League Questionnaire in Haefner player file at the Hall of Fame research center.

6 Email to author from Kurt Haefner, January 21, 2022.

7 Haefner Family Tree, maintained by Scott Haefner, http://scotthaefner.com/scott/outline.html

8 Email from Kurt Haefner, January 21, 2022, and from 1930 U.S. Census.

9 Frank (Buck) O’Neill, “Haefner, Mighty Mite with a Lot of Fight, Out to Prove Size is Over-Emphasized,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1943: 8.

10 Email from Kurt Haefner.

11 Email from Ruth Markham, based on information from her brother, Nolan Haefner, February 2, 2022.

12 O’Neill.

13American League Questionnaire.

14 Telephone conversation with Kurt Haefner, January 19, 2022.

15 American League Questionnaire.

16 O’Neill.

17 Conversation with Kurt Haefner.

18 O’Neill.

19 Shirley Povich, “This Morning” column, Washington Post, March 3, 1948: 19.

20. Povich, The Washington Senators (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1954), 215. Baseball-Reference.com says infielder Ray Hoffman, who had a brief trial with Washington in 1942, also was part of the deal, but he left baseball and never played for Minneapolis.

21 Povich, “Small Rookie Seen as Big Help to Nats,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1943: 5.

22 Email exchange with Ruth Markham, Mickey’s daughter, January 25, 2012.

23 O’Neill.

24 Bradlee, The Kid, 268-269.

25 Phil Bergen, “The Curse of Mickey Haefner,” The National Pastime (SABR), Volume 17, 1997: 17.

26 Keith Olbermann, “So, Are We Sure About These Tigers Scrimmages?” Baseball Nerd online web site, posted October 20, 2012).

27 Washington finished last in 1949. The nine wins in a row was a record winning streak, prior to expansion, for a team that finished last. SeeThe SABR Baseball List and Record Book: 377.

28 Burton Hawkins, “Haefner Says Wind Aided Him to Club’s 8th Straight,” Evening Star, May 11, 1949: C1.

29 Povich, “This Morning” column, Washington Post, May 3, 1948: 19, and “Griff Still Plans to Let Haefner Go,” Washington Post, July 16, 1949: 10.

30 Hawkins, “Victim of Nats’ Slump, Says Haefner, Fired as Griff ‘Blows Top,’” Evening Star, July 8, 1949: 15.

31 Povich, “Griff Sill Plans to Let Haefner Go.”

32 Povich, “This Morning” column, The Washington Post, July 9, 1949: 10.

33 Email from Ruth Markham, January 26, 2022.

34 Obituary for Milton A. Haefner, Journal-Messenger, New Athens-Marissa, Ill., January 12, 1995 (page unknown, clip from Hall of Fame research center file), and email from Kurt Haefner.

35 Email from Steven Woodward, New Athens Historical Society, to author, April 23, 2023.

36 Email from Ruth Markham, January 26, 2022.

37 O’Neill.

Full Name

Milton Arnold Haefner

Born

October 9, 1912 at Lenzburg, IL (USA)

Died

January 3, 1995 at New Athens, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.